November 13, 2018

I.

For the past seven years, environmentalists in B.C. have been looking for trees just like it — wide, tall and centuries old — big, ancient trees that erupt out of the ground and make people standing beside them look minuscule and insignificant.

They could be red cedar, Douglas fir, hemlock or sitka spruce, at least 250 years old and dominant in the densely forested landscapes where they grow.

In May, an hour’s drive southwest from the Vancouver Island logging town of Port Alberni, a group including TJ Watt and Andrea Inness found one — a giant Douglas fir measuring 66 metres tall and three metres in diameter at chest height.

“It’s kind of like coming across a unicorn,” said Inness, 36, who grew up on a small island off Vancouver Island and talks about old-growth giants with a religious reverence.

The pair, who work for the environmental group the Ancient Forest Alliance, figured it was the ninth largest tree of its kind in Canada and around 800 years old.

“Trees of that size are so few and far between now … less than one per cent remains of the old-growth Douglas fir stands, so we were giddy with excitement,” said Inness.

But two weeks later, the giant fir was cut down by loggers who say it was rotten in its core and worth more being turned into products like wooden beams than living out its life in the forest.

“It creates a lot of revenue,” said fourth-generation logger Jeremy Matkovich about old-growth trees like the fir. “It has supported my family, my dad's family — it's going to be [the same for] my kids' family, probably their kids.”

The tree is — or was — a symbol of the latest iteration of B.C’s War in the Woods where, on one side, environmentalists want all old-growth trees off limits to cutting because of the role they play in preserving biodiversity and keeping climate change from advancing.

The other side — forestry workers — wants at least some old-growth trees available to logging as the wood is valuable and important to an industry that supports more than 140 rural communities across the province.

II.

Many Canadians know Douglas firs as well-shaped and fragrant Christmas trees in their homes, but in B.C.’s temperate rainforest, they can reach staggering heights and live for up to 1,000 years.

It can rain up to 250 centimetres a year in these rainforests, which are along the coast of B.C.’s mainland, Haida Gwaii and western Vancouver Island. All that moisture feeds an ecosystem perfect for trees to grow into massive green and growing monoliths.

Stepping into a grove like the one where the giant Douglas fir was discovered is like pushing through a heavy curtain of green and entering into a dimension where the only sounds you hear are the sway of massive branches in the wind, the dripping of moisture and the soft crunch of your feet sinking into dense, soft earth of rotting wood and fern fronds.

The air is dank and dense with oxygen, the smell slightly sweet and deep.

Both loggers and environmentalists agree that there is a big wow factor when they come across a truly big old tree.

“It's breathtaking to stand before something that's lived for upwards of 1,000 years,” said Watt. “It’s a truly humbling experience.”

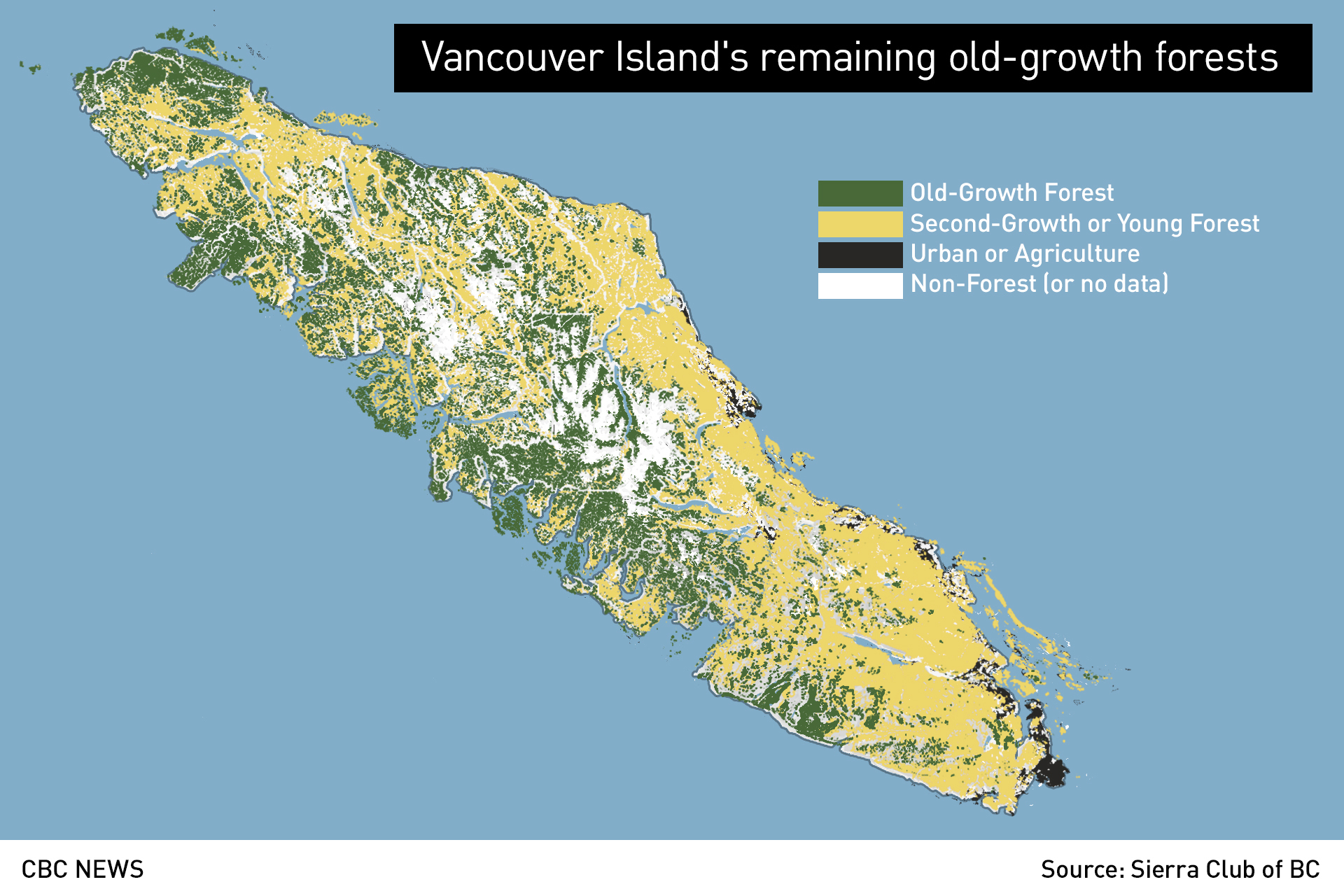

The province says there are 1.9 million hectares of forests on Crown land on Vancouver Island. About 840,000 hectares of that is considered old growth and out of that, the province says 520,000 hectares are protected from logging.

Still, the Sierra Club of B.C. estimates that around 10,000 hectares of old growth, 100 square kilometres, is being cut each year.

One of the Ancient Forest Alliance’s 10 demands for the industry is to transition to only cutting second growth trees, leaving all old growth to remain, live, die and help the groves exist and thrive. Second growth forests are made up of replanted trees that get harvested every 50 to 100 years.

Loggers say significant groves of old-growth forest are already protected and the industry is transitioning to second growth, but to stop cutting old growth immediately could put whole towns out of work.

It’s been 25 years since 800 people were arrested as they tried and succeeded in saving the ancient forests of Clayoquot Sound near the coastal towns of Tofino and Ucluelet.

Loggers themselves respect those turbulent years, saying that forest practices were modernized as a result. The rate of cutting dropped and there were also changes to better manage ecosystems.

III.

Ancient Forest Alliance campaigner Andrea Inness looked sad when asked about the big fir being cut down.

“[It’s] a little bit like coming across an elephant that’s been shot for its ivory and it’s wrong,” she said. “[It’s] a little bit hopeless that the ninth widest tree in Canada can’t be protected ... what hope is there for the rest of endangered eco-forest systems?”

She stood in a special place for the Ancient Forest Alliance called Avatar Grove, which is a 20-minute drive from Port Renfrew on the southwest coast of Vancouver Island.

Inness looked up to the top of another Douglas fir, which is not as big as the one that was taken, but still impressive. Its roots have formed a sort of platform above the spongy earth where it grows. Its trunk is dense and gnarled and wide. Inness craned her neck back to try and glimpse its top.

“You know, I get a profound sense of just connection to nature, connection to the past,” she said about this area.

“This is what Vancouver Island is supposed to look like and did look like for many, many thousands of years.”

Avatar Grove, (yes, named after the movie) is the alliance’s showcase for old, ancient trees.

TJ Watt first went into the area in 2010 and took Ancient Forest Alliance founder Ken Wu to the green and lush ravine leading down to the Gordon River the following year.

At that time, there were markers hung from trees, put there by logging surveyors, but no cutting permit had been issued.

Watt and Wu knew it was a special area with several large and impressive Douglas firs, but also red cedars that were unique and old because of the giant burls on their trunks.

After photographing the trees, they set to work advocating to have the area saved from logging, built stairs and boardwalks for easier access for visitors and applied to the province to have the area designated as a recreation area.

Now thousands of people come each year to walk through and take photographs of themselves standing beside the trees.

Port Renfrew has also since rebranded itself as Canada’s tall tree capital, hopeful that tourism dollars will be its key economic driver rather than logging or fishing.

“It brings me such joy to hike here throughout the summer months. You bump into people from all around the world, many … say it’s the most beautiful place they have ever been,” said Watt, who owns a home in Port Renfrew.

“But at one point in time its future was uncertain.”

The big tree hunters hope to develop other groves like this, creating showcases for people to see and experience these ecosystems.

“Avatar Grove … has been an incredibly useful tool for advocacy and for getting people connected to these amazing forests,” said Inness.

IV.

What groups like the Ancient Forest Alliance are doing has resulted in a new version of the War in the Woods, a public relations battle over B.C.’s iconic old trees that is playing out online, in political lobbying and during hikes in the forest rather than with civil disobedience and arrests like the summer of 1993.

Inness, along with Watt, a soft-spoken 34-year-old who grew up skateboarding outside Victoria, and Wu, 44, are full-time big tree hunters looking for specimens they say are anchors of B.C.’s unique coastal rainforests.

“I feel truly lucky that we still have some of Earth's last temperate rainforests right here on Vancouver Island,” said Watt. “[The] passion in my life is exploring and documenting these landscapes, hopefully resulting in their protection.”

Their campaigns dispute the province’s numbers about what amount of old growth is left. Wu argues that the province includes old-growth trees that exist in hard-to-log areas or places where they actually don’t grow that big or contribute as much to ecosystems as their giant cousins in lush valley bottoms.

“It’s like adding your Monopoly money with your real money and saying you are a millionaire,” said Wu.

The B.C. government fails to mention the context of how much old growth has been previously logged, said Wu. The AFA estimates that to be 75 per cent or about 1.5 million hectares of the original two million hectares of productive old-growth forest on Vancouver Island.

Environmentalists like those with the AFA say that remaining huge and ancient trees are worth far more to the unique ecosystem of the coastal temperate rainforest than being cut down and milled.

They support diverse ecosystems and even when they hollow in the middle, die, fall over and rot, they help support the growth of new trees, plant life and animals.

Some First Nations want also old growth preserved for cultural and environmental reasons. There is also an economic model showing their value as tourist and recreation destinations.

To strengthen these messages Inness, Watt and Wu push through yet-to-be-logged wild areas on public land to find trees like the big fir. They photograph the giants to reflect their stunning size and age. The goal is to hopefully drum up support over social media from residents to call on governments to keep them from being logged.

“To fight to protect something, you need to know about it and care about it and I think photography as an art form, especially, helps bridge that gap and make people aware about these incredible old-growth forests that are home to some of the largest trees on Earth that are still actually being cut down in many cases,” said Watt.

V.

Forestry workers — loggers — have themselves been outspoken about the photos and campaigns organizations like the AFA are doing, saying they hurt their industry at a time when changes could be coming from the provincial government on how Crown land and its resources are managed.

“It puts a bad name to everyone out here trying to make a living,” said Jeremy Matkovich, 42, a third generation logger from Campbell River.

His grandfather worked in an era when horses were used to haul logs out of the forest.

His father is still logging and his two sons, 19 and 21, are also loggers.

He stood in a cut block devoid of standing trees, wore a high visibility vest and defended the industry that has supported his family and his town for a century.

“We do it in an environmentally safe way,” he said about modern day logging.

“I don’t think [people] understand how many products they actually have in their home from logging.”

With Matkovich was Zoltan Schafer, a registered professional forester who started working as a logger when he was 14 years old.

He’s known as Zolie and seems to know pretty much everything and everyone involved with logging on Vancouver Island. He turns 60 this year and says much has changed since he started in the 1970s.

“It’s been a drastic change,” he said, adding that the Clayoquot protests really paved the way for these changes.

“I think the environmental movement was probably a good thing to wake up the industry but I think the balance has to come back.

“Are we always going to have old-growth timber?” he asked. “Yes.

“Maybe not in the percentage that certain people want, but we have reserves. And it's going to stay.”

From the air on a helicopter ride to the area around Nahmint Lake, outside Port Alberni, Schafer pointed out dense groves of old growth that he says won’t be logged. Their scraggly tops, poke out above other trees along the water’s edge.

The tour was organized by the Truck Loggers Association, which represents loggers working public lands. Up above the landscape, yes there are bare, clear-cut areas, but it's hard not to notice the vibrant green tree tops where old growth is or the emerald carpet of second growth trees.

There are still so many trees, either there for hundreds of years or replanted in the past 50.

The area the helicopter set down in was recently cut. Hundreds of logs still littered the landscape, the smell of sawdust and earth was strong and fragrant.

Schafer showed us around, walking up and down one of the access roads built to get at the trees. He has the body of a hockey player, wore a yellow and orange high visibility vest and kept his hands tucked in his waistband.

He wore his baseball hat at an angle on his head but his boots were well-worn and when he talked about changes to the industry, he was serious.

“They don’t try and clear cut anymore. They try and leave mosaics,” he said about the area.

What he is talking about is how modern logging looks. Gone, he said, is the complete mowing down of trees off entire hillsides, leaving 100 hectares of nothing but stumps and garbled up leftover trees, rocks and mud.

Loggers now leave parcels or swaths of trees of different sizes within and around the cutting areas, what Schafer calls mosaics. This is intended to help preserve the natural diversity of the area and help it when it’s replanted.

In January, the province also published a special legacy tree policy to help loggers assess large, ancient trees that should be kept from being cut. The government is reviewing it to potentially strengthen it.

Still, old-growth trees — the giants — are prized.

Schafer walked over to one that had been cut down, chopped into chunks beside the access road we stood on. It’s a big red cedar, probably somewhere around 300 years old.

Schafer counted the rings and pointed out how blemish-free the wood is, how at a mill it can be made into high value lumber or even even high-end furniture or musical instruments.

“This is what we call a 'money tree,'” he said.

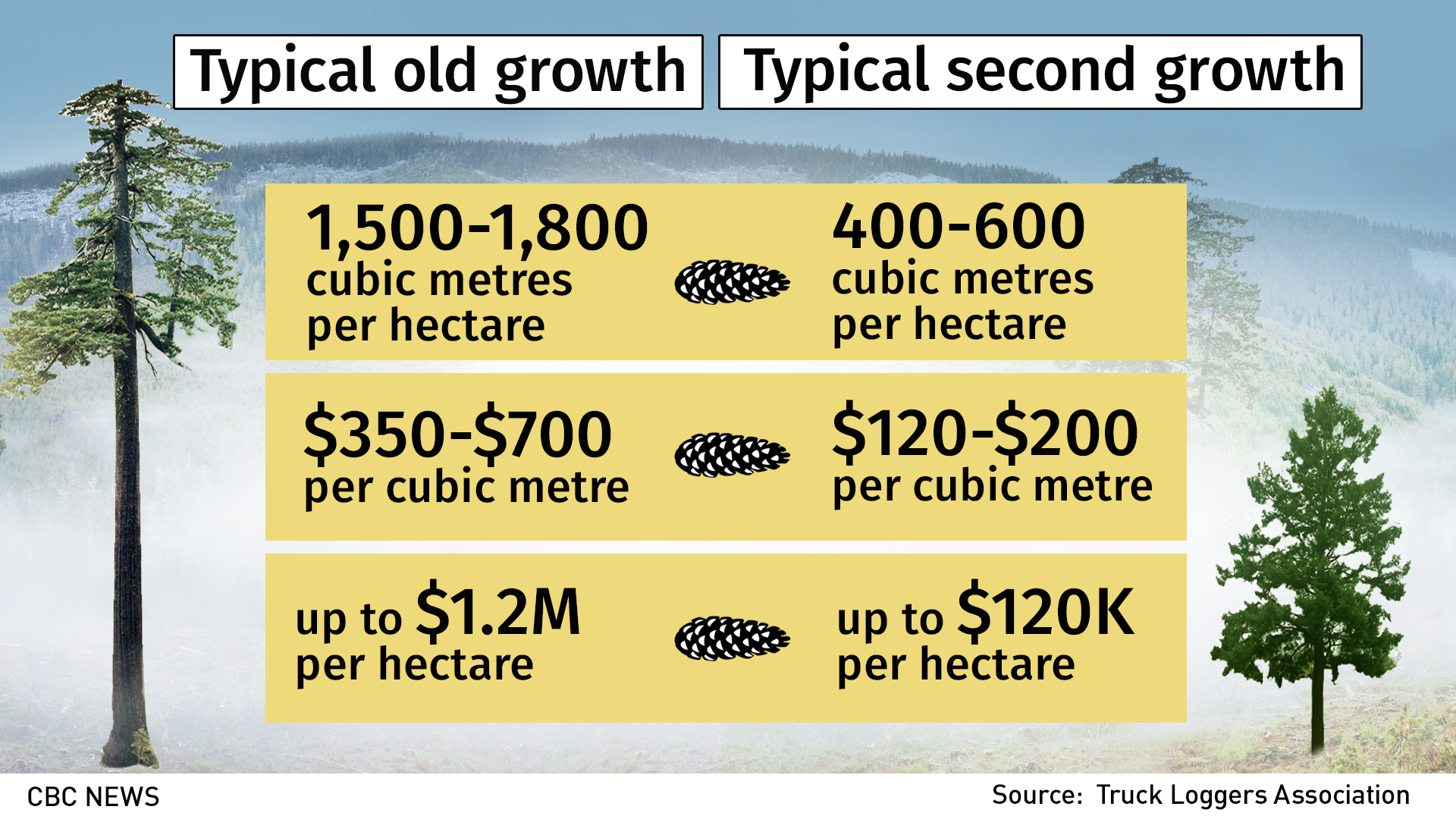

According to the Truck Loggers Association, these types of trees are worth far more than second growth trees.

Typical coastal old-growth sites can yield as much as 1,500 to 1,800 cubic metres per hectare whereas second growth sites yield around a third of that because they are harvested at younger ages, according to the TLA.

If you picture a cubic metre as a box, it has 1,000 litres of space.

Old-growth logs fetch around $350 per cubic metre for lumber-quality logs and $700 per cubic metre for high-end grades. By comparison, second-growth logs range between $120 and $200 per cubic metre.

It’s not hard to understand how old growth has kept logging as a viable industry along B.C.’s coast. Based on the TLA’s numbers, logging one hectare, or 0.01 square kilometre of the highest quality old-growth trees, could potentially generate wood worth more than $1 million.

As Schafer walked through the area pointing out old-growth trees that are currently off limits to cutting, he explained how increased protections have come, and continue to come, but to transition immediately out of logging any old-growth trees to just cutting second growth is not doable.

“We have to have a balance,” he said.

The TLA agrees and says that the current proportion of the harvest from coastal second-growth forests has risen steadily over the last decade from about five per cent of the harvest in 2000 to about 50 per cent of the total harvest today.

Leaving every remaining old-growth tree standing on Vancouver Island would result in the closure of four saw mills, at least one pulp mill and spell the end of the cedar shake and shingles industry, according to the TLA.

Schafer said the industry is sustainable with its current practices.

“I think there is a balance and I think it’s being done and I don’t think you are going to satisfy everybody,” he said. “You never are.

“I think the loggers do care, the ones I have dealt with and work with. We all try and do the right thing ... protecting the streams and wildlife, cleaning the block up, getting it replanted.”

Schafer said this right where the big fir, described as a unicorn, was logged in May, two weeks after it was recorded by environmentalists.

The province’s legacy tree policy didn’t end up protecting it because the area was auctioned off by the government before the policy took effect.

"It was completely rotten."

No matter, say loggers like Matkovich who argue the tree was better served coming down than left standing.

“It was completely rotten,” said Matkovich. “It only had probably 50 years left and it would have blown over anyways.”

They resent the photos the AFA took and posted online of the tree cut from its base and lying prostrate on the ground.

VI.

Many people working within B.C.’s logging industry know that times continue to change and some are already getting prepared for there being less old growth to cut and mill.

On the shores of the inlet outside Port Alberni, fourth generation logger Mike McKay showed us his sawmill, Franklin Forest Products.

It was a logging camp in the 1930s before being converted to a sawmill in the late ‘70s.

His father brought it into the modern area in the 1990s and now McKay is taking it further.

He pointed to a structure of beams, belts, ladders and steel — a processor that can mill second growth logs.

“I’m going to take one last kick at the cat,” he said about the seven-figure investment he hopes will give his mill a future.

McKay, 48, employs 35 people.

“I am proud of that,” he said out from under his hard hat, which is emblazoned with maple leaves and the words “Canada Strong.”

“Sometimes it’s a little bit of pressure to keep them all employed but we seem to be doing a good job.”

The mill once had 70 workers before downturns in the industry. It also used to only cut old-growth logs, but now, 75 per cent of what McKay turns into fence posts and lumber is from old growth, and 25 per cent is from second growth.

“I think there is a transition period that we all need,” he said, adding that if there was an immediate transition to second growth logging only, his mill would go out of business.

McKay said there has been a significant preservation of old-growth forests around Port Alberni. The rest, he said, need to function as working forests, meaning they should be cut and replanted at intervals.

While environmentalists like Watt and Wu describe these working forests — second growth groves — as “astroturf” because of how uniformly they look from the air compared to old-growth groves, they do recognize their utility.

The AFA is supportive of a second growth industry and wants the province to help people like McKay retool their mills to be able to process it. But they also say curbing the export of logs from B.C. to overseas would equally help.

The Ancient Forest Alliance is looking to the B.C. NDP to make good on its 2017 election platform, to partner with First Nations to further modernize public land use planning, which is managing land in ways that meet economic, environmental, cultural and social objectives.

That could include coming up with more huge protections like what was done in the Great Bear Rainforest on B.C.’s central coast. An area the size of Vancouver Island is now off limits to logging.

In its 2018 budget, the province committed $16 million over three years to land use planning and the forestry ministry is reviewing how it treats old growth as part of that.

Ancient Forest Alliance campaigners say they’re waiting to see what comes from the province while continuing to push their way through the dense groves on Vancouver Island to find more old-growth trees to wow the public and policymakers with, like that huge Douglas fir they found in May.

“Holy moly — that’s a hell of a cedar,” Wu said as he scrambled through the fern-covered forest floor of yet another grove already surveyed for logging.

He stood up against the trunk of the massive cedar and posed for a photo taken by Watt.

They’re hopeful impressions like this will do something to keep these old giants from being felled but realistic that loggers will most likely get here first.