May 4, 2021

Hundreds sick. Three dead. And fear — of sickness, of not making rent, of neighbours laying blame because of where you work, the colour of your skin, the language you speak.

This spring, a coronavirus outbreak swept through an Olymel pork-processing plant in Red Deer, Alta., leaving devastation in its wake.

But it wasn't the first time this had happened.

Just under a year earlier, 185 kilometres south of the Olymel plant, past the ranches that supply much of Canada's meat, the same death toll and an even higher case count ravaged another plant — Cargill in High River, the site of the country's largest COVID-19 outbreak.

"It's like deja vu … it's the same situation," said Cesar Cala, a Filipino community activist who has been supporting meat-packing workers in Alberta.

"And again, the workers seem to be the ones suffering the brunt of this decision to keep on operating the plant at whatever cost and no really significant change to safety in the workplace."

How did such a large, and deadly, meat plant outbreak happen again? And will this be the last time?

CBC News spoke to eight current workers at the two meat-processing plants for this story. Workers were given pseudonyms so they could speak openly without fear of professional reprisal.

Both companies say they have followed strict pandemic safety protocols and have worked to safeguard and support their employees. Both say provincial health and safety officials validated the steps they took before, during and after the outbreaks.

Slaughterhouse workers say the first thing outsiders need to understand is their problems started well before the pandemic.

On the line

On her first day at the Olymel pork plant, a large, busy industrial warehouse in northeast Red Deer, the first thing Analyn felt was pity as she watched semi-trailer trucks drive on the lot, hauling the pigs for that day's operations.

Oh, those poor pigs, Analyn said she thought as she watched the squealing pigs being led off the truck into the plant. But what can I do? I need to work.

This wasn't where Analyn envisioned herself working when she first moved with her family to rural Alberta from the Philippines years ago.

After Analyn and her husband divorced, she and her children moved to Red Deer — a hub for oil, gas and agriculture located about halfway between Edmonton and Calgary.

Finding work in the community was difficult. Analyn had limited success until a friend suggested she apply at the meat plant, which at that time employed around 1,200 workers.

It was a diverse workforce — there were workers from China, Vietnam, Ukraine, South America — but most of all, there were Filipino workers like Analyn.

"It's hard labour. And I thought I will be only working there for a year," she said. "It's not an easy job."

Outside the plant, where Analyn saw pigs being hauled inside, she already noticed the smell.

Inside, on the kill floor, it was worse. The smell of blood and feces hung in the air around the carcasses of slaughtered pigs on hooks.

Analyn was tasked with taking meat off the processing line and putting it into huge cardboard boxes to get it ready to ship.

A year passed. Then another. Analyn got a raise and was put on the line to trim meat on a conveyor belt.

It was here that Analyn began to feel like a machine. Production quotas continued to increase, and her work needed to follow suit.

Another worker, Gabriela, said the production lines are hectic, with employees working "shoulder-to-shoulder," and cold. If you're lucky enough to work in one of the chillier areas, the cold neutralizes the smell of the meat. Glasses sometimes fog up, even before the addition of face masks.

The pieces of meat come one after another: up to 45,000 hogs per week that need to be neatly disassembled and placed on styrofoam trays for eventual display on a grocery store shelf.

"You're doing all this [with a] million things going on in your head … focusing on doing the cut properly, that the next piece is coming … when we have to clean a tenderloin, it's four to five seconds. So it's boom, boom, boom, boom, boom, boom. You know, it's just, it's so fast,” Gabriela said.

The repetitive work quickly took a toll on Analyn's body. She tore her meniscus by bending too much, suffered wrist injuries and watched her hand become inflamed.

She said she saw worse injuries among her colleagues. Carpal tunnel syndrome was rampant.

The more bloody incidents really bothered her, she said, such as when a new hire caught his palm in one of the machines, stamping a hole in it. He didn't come back to work.

Sometimes, when her co-workers got hurt, Analyn said management told them it was their fault for not following safety measures or if the worker had a second job, blamed the injury on the other workplace.

"They will blame the worker. They will make a way," Analyn said. "'Maybe that injury is from your second job.' They always say that."

An inside look at a COVID-19 outbreak that tore through an Alberta slaughterhouse, as seen through the eyes of the plant’s employees — and what their stories reveal about the situation facing essential workers across Canada.

Richard Vigneault, a spokesperson for Olymel, said the company's goal is to keep workers as safe as possible.

"[If] management or staff do not follow the robust safety programs and training they have received, they could be hurt," he said.

Those who "repeatedly or seriously violate" safety rules will sometimes be retrained or will face a progressive discipline measures, he said.

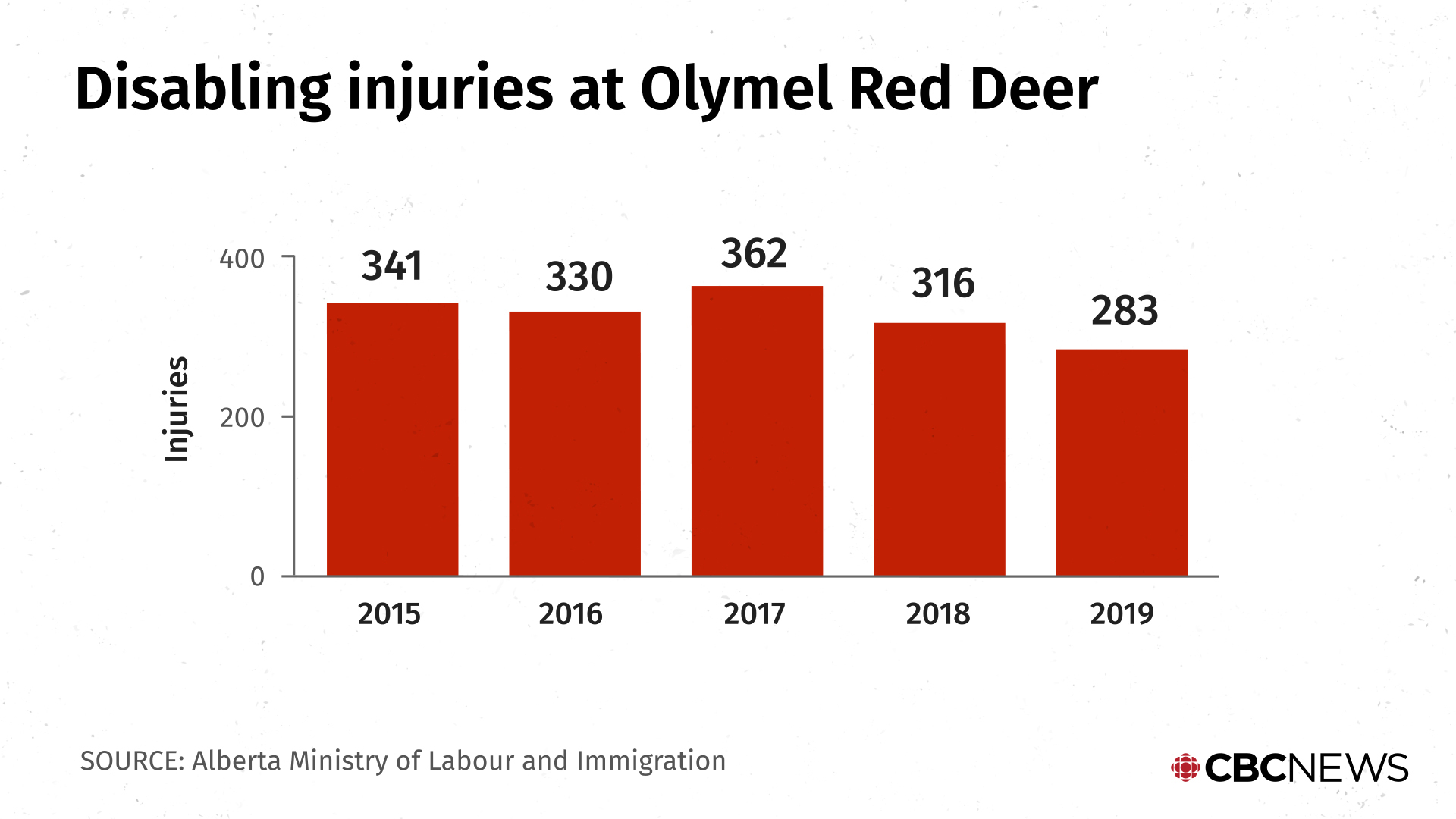

The plant sees hundreds of disabling injuries each year, according to Occupational Health and Safety, which enforces provincial workplace safety regulations.

Sean Tucker, an associate professor of human resource management at University of Regina who specializes in worker safety, said that in a meat processing plant, workers are forced to adapt to the equipment rather than the other way around.

"The human body is not designed to work in an environment like that," Tucker said.

"You're engaged in repetitive motion, often putting a lot of pressure on joints, muscles, tendons. Over time, that can take a toll on the body."

Tucker said that even for the meat processing industry, Olymel stands alone when it comes to its injury rate.

In 2019, the Olymel plant's disabling injury rate — which applies to workers who were injured at work, required medical attention or couldn't work their next shift — stood at 18.1 per 100 full-time employees compared to a rate of 2.9 at Cargill in High River and 6.6 at the JBS Canada beef facility near Brooks, Alta.

In other words, Tucker said, an average of almost 1 in 5 employees at Olymel suffered some kind of injury at the Red Deer plant that year.

"Any time you see a company that's 100 per cent, 150 per cent, 200 per cent higher in their injury rate, it just stands out," Tucker said. "And it's not acceptable; it's not normal practice."

Vigneault said Olymel brought down its total disabling injuries from 283 in 2019 to 248 in 2020, but those numbers haven't been listed yet in Alberta's OHS database.

The nature and pace of the work and the injuries took their toll on Analyn.

"I feel sad of what's going on, but I'm just fighting … because I need a job, and I need a good benefit for my children. [As a] single parent, I need to persevere."

Roughly a decade later, as the COVID-19 pandemic was in the midst of its second wave in Alberta, Analyn was still at Olymel.

The plant's workforce had grown by a third since Analyn was first hired.

According to the union that represents workers at the plant, approximately 80 per cent of Olymel's staff are first-generation Canadians, and around 60 per cent of those are Filipino.

For many of the plant's 1,850 employees, the wages aren't enough to support a family or send money back home — around 60 per cent hold second or third jobs, according to Alberta Health Services.

Analyn said she works full time at Olymel for $21 per hour plus another 32 hours per month at a second job.

The outbreak spreads

Late last year, about eight months after the first coronavirus case was confirmed in Alberta, cases started popping up at the Olymel plant. The virus was still relatively new, but ways of reducing the risk of transmission were common knowledge by that point: stay two metres apart, wear a mask and if you're sick, go home.

Olymel said it followed those protocols — taking temperatures, ensuring staff wore face masks and installing plexiglass dividers, among other measures.

Gabriela said employees who worked on the lines with those who contracted COVID-19 were being tested but were told by the company nurse to continue working if they were asymptomatic as they waited for results.

"They were getting people tested and putting them back on the line," she said. "Now, you tell me how in the world that makes sense to anybody … how many people were contagious already?"

Vigneault, the spokesperson for Olymel, disputes that allegation.

"Workers who were required to isolate were not asked to work," he said. "This statement goes against health guidelines, our internal policy, which is in excess of the guidelines, and is in direct contradiction with our messaging to staff."

In late January, one of Gabriela's co-workers — 35-year-old Darwin Doloque — was found dead at home of COVID-19, having contracted the coronavirus at Olymel.

"He was just friendly and just bubbly," Gabriela recalled. "He was never in a bad mood. He was always trying to make everybody laugh."

Gabriela said she felt the company or government could have taken action sooner by closing the plant before spread got out of control.

"In my mind … the company could have done something about it. That was, I think, that was the first thought that came … how many more people are they going to wait to see gone until they do something about it.

"And they still waited. So, that was the hardest part."

Nearly three weeks after Doloque's death, on Feb. 15, Olymel abruptly changed its position. Hours after telling CBC News it planned to remain open, the company said it would temporarily shut down the plant as it was no longer safe.

At that point, 326 workers had tested positive. The province said it had no part in Olymel's decision as it had deemed the plant safe to continue operating.

It takes a few days to wind down production at a meat plant. The outbreak grew bigger. By March, there were more than 500 cases.

Two more workers died.

Henry De Leon, a grandparent of two in his 50s who came to Canada from the Dominican Republic 16 years ago, died in late February. The union said he contracted COVID-19 after it began to call for the plant to close but before the company agreed to shut down. Another worker, whose identity has not been made public, died the next week.

One year earlier, the Cargill plant saw a similar toll. Three members of the community died. Hundreds of others who had been infected with COVID-19 had lingering symptoms.

At least 950 staff at the Cargill beef-packing plant — nearly half the workforce — tested positive for COVID-19 by early May 2020, and hundreds of family members and other close contacts were sick. By the time the Olymel outbreak was growing this spring, Alberta's provincial government was no longer providing the total number of cases linked to an outbreak (just employees), so it's difficult to directly compare the two outbreaks.

At Cargill, workers Hiep Bui, 67, and Benito Quesada, 51, died of COVID-19, as did a worker's 71-year-old father, Armando Sallegue. The outbreak there is currently the subject of a police investigation and the company a target of a class-action lawsuit. No charges have been laid, and the lawsuit's allegations have yet to be tested in court.

While Cargill has said it can't comment on pending litigation, the company maintains it worked closely with provincial health and safety officials to add safety measures as they became available during the pandemic.

'Two sharp edges of a knife'

Cala, the Filipino community activist, has been continuing to support workers at Cargill. He said he's seeing mental health issues emerge.

Many employees at both plants are migrant workers who came to Canada through the temporary foreign worker program, and the financial hit of having to take time off work to quarantine has been difficult.

"Many of the workers already feel like they're second-class, right? Coming in, even the designation of temporary and then foreign, like double-whammy on their situation. Then, with the experience of not being heard … it really creates this sense of alienation and isolation," Cala said.

"Of course, they have no choice but to follow what the company has stated in terms of expectations of going back to work, even if they don't feel safe.

"We have a saying in the Philippines: 'You're holding on to the two sharp edges of a knife,' like, you have no choice."

Jamie Welsh-Rollo is a worker and a shop steward for the union at Cargill in High River. She said safety measures put in place at Cargill after the outbreak could have served as a model.

"If it's working for us, it should be working for them. It seemed like Olymel kind of ignored the warning signs," she said.

Cargill increased space in its break rooms by opening up meeting rooms to workers, reassigned lockers in its locker room to streamline the flow of workers, installed protective barriers throughout the plant and provided buses fitted with barriers to alleviate the need for carpooling.

However, those measures didn't necessarily halt spread at Cargill. The plant is currently experiencing a second outbreak in which 96 workers have tested positive.

Ben Chapman, a food safety specialist with North Carolina State University in Raleigh, is studying what can be learned from the pandemic to protect employees in the food and agriculture sector.

"These are our essential workers who, you know, you and I benefit from eating food every day because of, because of this type of work that happens," Chapman said.

Olymel is Canada's top pork supplier, and Cargill is the country's biggest suppliers of beef.

Over the past year, experts like Chapman have learned more about how spread happens in meat plants.

"It's really hard to do the social and physical distancing just because of the way that the plants and those systems are set up," he said.

"What's really difficult right now is to sort of retrospectively go back to see how well all of the measures that we know are important for production were being enacted."

What experts do know is that the cold, low-humidity spaces are ideal environments for airborne transmission of a virus. Workers crowding tightly together and shouting to be heard over the noise also contribute to spread.

According to the Food and Environment Reporting Network, a non-profit group based in New York, the U.S. has seen more than 58,000 COVID-19 cases among workers at more than 1,400 meat-packing plants. Canada lacks the same kind of data but has had cases at dozens of plants across the country.

A report by the European Federation of Food, Agriculture and Tourism Trade Unions points to poor housing conditions, decreased workplace inspections and job insecurity as some of the reasons for COVID-19 spread among the mostly migrant workforce in Europe's meat-packing industry.

Feeling blamed

Yet, at both Cargill and Olymel, blame has landed at the workers' feet.

In early February, Vigneault, Olymel's corporate spokesperson, flagged that a potluck meal held on site might have contributed to the spread.

Dr. Deena Hinshaw, Alberta's chief medical officer of health, also downplayed workplace environmental factors in a press conference, saying Olymel had successfully managed to keep transmission low for months.

"Unfortunately, I think there were a concurrence of a number of events that were not limited to events directly on that plant site, and therefore we did see an increase in cases," she said in February.

The Red Deer Advocate, a local newspaper, published an article with a photo of workers gathered around a table, with the headline: "Maskless Olymel workers partied as COVID cases at the Red Deer meat plant grew."

But workers said that photo was actually taken last year, months before the current outbreak began, when there were no cases of COVID-19 at the plant.

The article was quickly deleted, but workers felt like the damage was done — especially when they noticed a trend of hurtful comments online.

"It felt like discrimination. Those comments on Facebook, lots of them are racist," said Analyn of the response on social media at the time.

"They're even telling us we have to go back to our own country and let Albertans work … and it's unacceptable. It's really sad.”

That same blame was felt by the Filipino community at Cargill last year.

Emails, obtained by a freedom of information request by the union, show Hinshaw was aware of transmission between food inspection workers at Cargill hours before she held a town hall with workers at the plant. But she didn't tell them that information and instead reassured them the work site was safe.

"I don't want to give the impression that I think the work site in Cargill is a site that has a lot of virus in the environment, I don't believe that to be the case," she told workers.

Later, Hinshaw would emphasize the role that carpooling and household transmission played in spreading the virus, without pointing to dangers in the plant.

Welsh-Rollo said she was frustrated to see the Olymel workers blamed as they had been at Cargill.

"They, again, blamed the Filipino community. And, that's so frustrating," Welsh-Rollo said.

"It breaks my heart … there's no other way to put it, but it's racist."

As the outbreaks were growing and before the plants were closed, Cargill was inspected by video call while Olymel was inspected 14 times, both in-person and by video call.

At both Cargill and Olymel, provincial health and workplace safety officials deemed the plants safe to stay open. At both plants, the companies voluntarily shut down production — but only after hundreds of people became ill with COVID-19 and cases were spreading to the broader communities.

CBC News has reached out to Alberta's labour ministry to ask if, in light of these outbreaks, the government plans to change how it regulates and inspects facilities and whether it is continuing to investigate what led to the six deaths. A spokesperson for Occupational Health and Safety said the department continues to monitor workplaces to ensure they are compliant with legislation and the current orders from the chief medical officer of health. The spokesperson did not confirm whether or not the outbreaks are still under investigation.

Tucker, the University of Regina workplace safety expert, said in the case of Olymel, warning signs — such as an early cluster of cases — should have at least led to a slowing down of the line, if not a shutdown.

But a common denominator among meat processing plant outbreaks during the pandemic, he said, was a tendency to not learn from the past.

"Industry and regulators seem to be unable to implement learnings from outbreaks across Canada and North America and other places in the world," Tucker said.

The 'essential' worker

Gabriela said at Olymel, the company marked her colleagues' deaths with a moment of silence.

"I don't think the company understands … giving us [one minute of] you know, silence, it's not going to bring them [back] … it's not going to give the family peace and it's not going to give us any peace either," she said.

Jacob, another Olymel worker, is still struggling with the lingering symptoms of COVID-19 he contracted at the plant.

He spread the illness to his family, and months later, still sometimes struggles to breathe. He said he lost wages for the entire period of his sickness. He said it was only later through the union he learned he was eligible for workers' compensation benefits.

"They said we are essential. But we feel not essential with them. Their course of action is opposite of what is meant by essential," he said.

Alberta is now in a third, more serious wave of COVID-19. Coronavirus variant cases as well as cases among younger people are increasing.

The outbreaks at both plants are still ongoing, with seven active cases at Olymel out of 542 total, and five active cases at Cargill out of 96 total.

After some delays, vaccinations for meat-packing workers are now underway.

But, in some ways, the provincial government has rolled worker protections back.

A recent piece of legislation, Bill 47, means employees are now responsible for their own health insurance if they are off the job for a work-related injury. And, companies are now no longer legally obligated to reinstate workers hurt on the job.

The bill also limits the circumstances under which workers have the right to refuse unsafe work — specifying the work must immediately constitute a serious danger. It also removes the right to have a worker representative present while the unsafe nature of the work is investigated.

Cala said on-site, priority vaccination for essential workers isn't enough, and more needs to be done to keep workers safe.

He wants to see paid sick leave, so workers no longer feel pressured to work while unwell.

Stronger workplace inspection standards, with a closer focus on employee safety rather than corporate productivity.

A clearer path to citizenship for temporary foreign workers and others with precarious immigration status, so their ability to remain in Canada isn't tied so closely to their employers.

But most important, he said, is putting people like Analyn, Gabriela and Jacob at the centre of the conversation about workplace safety — not pointing fingers.

"These workers are experts of their conditions, and they need to be part of any kind of solution," he said.

"I think … vulnerabilities and inequities have been unmasked by this crisis, right. So the challenge for us is, do we then just pretend that they are no longer there if we go into normalcy or have we learned from this experience?"

Tucker has called for a public inquiry into the provincial response to the Cargill meat-packing plant outbreak.

Meat-packing plant workers have worked through some of the most dangerous conditions of the pandemic, he said. but unlike other frontline essential workers, the public doesn't have a window into their working conditions the way they would a grocery store clerk or a bus driver.

In Tucker's view, that means they may lack the voice and the political clout to make their concerns heard.

"These groups should've been prioritized for vaccines right away," Tucker said.

"But because they're invisible, because the public doesn't interact with them on a day-to-day basis … they haven't been at the table.

"I don’t believe this would happen if these were white workers. Let's just call this what it is."