June 10, 2020

A light breeze from Great Slave Lake adds a last bite of winter to the warm spring air as Chief Ernest Betsina walks through Ndilo, a Yellowknives Dene community down the road from Yellowknife.

After a few minutes, he stops at a high spot. The entire community stretches before him. He can see the abandoned Giant gold mine site across the bay. It's a festering wound, the worst-case scenario when a mine company goes under.

Today, another mining company, Dominion Diamond, is fighting off its own financial ruin. Its cash reserves collapsed amid the COVID-19 pandemic, leaving it with $1.2 billion US worth of debt it has no way to pay off unless it restructures itself through the courts.

The case has prompted serious fears about the future of one of the North's key employers, while pulling back the curtain on the international diamond trade.

"The Yellowknives Dene, we are the original miners of the North," Betsina said. "Our people are called Tetsǫ́t'ıné, which means metal, or copper people. Our people are very resilient."

The entire territory could use that resilience now.

The Yellowknives Dene have a mining tradition that stretches back across their history. They mined copper and other minerals, crafted tools and traded with other Indigenous groups.

In the 20th century, the gold mining industry exploited, even poisoned them.

During more than half a century of mining, an estimated 19,000 tonnes of toxic arsenic trioxide dust spewed from Giant's smelter stacks and those at the nearby Con Mine, settling on the once-pristine lands around Yellowknife and Ndilo.

In 1951, a Dene child died after eating snow contaminated by arsenic from Giant.

When the company that owned the mine went bankrupt, it became the responsibility of the federal government, which is still cleaning up the site 20 years after it closed. Betsina continues fighting for compensation from Ottawa for the damage inflicted by the mine.

Today, the First Nation is a key player in the territory's major industry. Its economic arm, the Det'on Cho Corporation, earned $56 million last year.

The Yellowknives Dene supply workers at all three of the territory's diamond mines, enrol workers into apprenticeship programs, and generally have a positive relationship with the sector, Betsina said.

"It's amazing," he said. "My people have survived all these years. Survived, and thrived."

Det'on Cho is also Dominion's largest northern creditor, owed about $5 million.

In the Northwest Territories, it's generally accepted that if someone doesn't work for the government, they likely work for a mining company or a company whose business relies on one.

According to the territory's latest industry report, diamond mining and related spinoff industries account for $2.25 billion of the territory's $4.9 billion GDP. About 1,600 people in the Northwest Territories work for three mines directly, including 253 at Dominion, while "countless other N.W.T. residents work for companies or organizations that exist because of mining activity," the report says.

They are high-paying, union jobs. The kind that are disappearing.

In Ndilo alone, 30 of the 400 people who live there work for Dominion Diamond. They're out of work while the Ekati mine is shut down.

"In effect, that's 30 families affected with the sudden stoppage of work," Betsina said. "I know these people. In fact, I know the majority of the people. I know them by name."

People in Ndilo are banding together, making food hampers, sharing geese hunts and catches of fish.

"We're helping out with groceries. Every little bit goes a long way," Betsina said.

Dominion Diamond is far from being the only company in this situation as the economic fallout from COVID-19 sinks in. But it may have the most riding on its success or failure — the economic future of the Northwest Territories.

The crash

The story of Dominion begins with treasure. Treasure buried in the barrenlands, in kimberlite pipes found deep in the Precambrian rock.

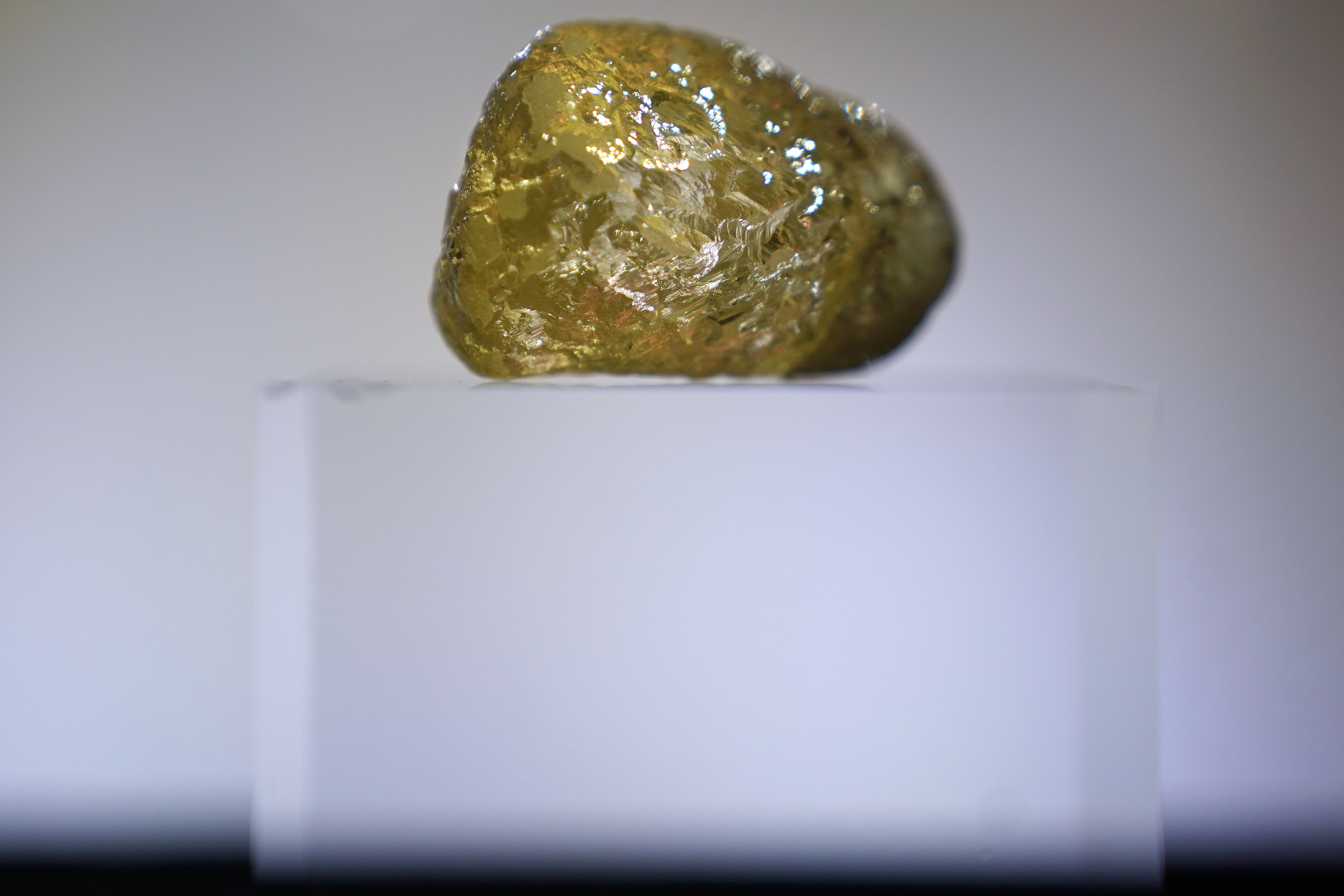

It's where some of Canada's biggest diamonds have been found, including a 552-carat yellow diamond from the Diavik mine in 2018. Roughly the size of an egg, it was three times as large as the next biggest diamond found in Canada — which also came from the Northwest Territories.

Dominion Diamond is a key player in this industry.

The company owns the Ekati mine and has a 40 per cent stake in Diavik, which is controlled by mining giant Rio Tinto. Gahcho Kué, the territory's third mine, is controlled by De Beers.

In 2017, Dominion became part of The Washington Companies, a U.S. conglomerate with shipping and manufacturing interests in the U.S. and Canadian Pacific Northwest. Owned by billionaire Dennis Washington, The Washington Companies bought up all the shares in Dominion in a deal worth $1.2 billion US, funded with a $550 million US bond from creditors.

Dominion has since worked in relative secrecy as a private company, freed from the obligation to open its books for public scrutiny.

That changed this spring as the COVID-19 pandemic rocked the global economy. Closures along the supply chain left Dominion with $180 million US worth of diamond inventory it couldn't sell, forcing it to seek creditor protection.

On April 22, Dominion announced its bid for protection. One of the most significant employers in the Northwest Territories was running out of cash.

It was only after Kristal Kaye, Dominion's chief financial officer, laid out the situation in nearly 150 pages of court documents that the picture became clear: The company owed multimillion-dollar debt payments that could only be made as long as revenue rolled in.

This type of leveraged business model generally makes sense as long there's enough money coming in to make the payments. And for a time, it did. Financial records revealed through the courts show the company grossed $151.3 million US in 2019, and $284.3 million US the year before.

The company’s foundation collapsed under the weight of COVID-19 health restrictions. Polishing facilities in India and Belgium are closed, so the company can't get its diamonds to customers.

In April, Dominion was unable to make two key payments: a $20 million US interest payment on the bond The Washington Companies used to buy the company, and a $16 million Cdn payment to its partner at Diavik.

On April 22, it went to the courts to avoid bankruptcy, using the Companies' Creditors Arrangement Act to keep its creditors at bay. That process is expected to continue throughout the summer, and it has left many in the territory wondering what's next.

"It adds to the stress for people," Betsina said. "Thinking about money, where they're getting the next payment for groceries, putting food on the table."

COVID-19 and the global diamond trade

Diamond mines around the world are feeling the same pressures as Dominion, and it may be just the first mining company to find itself on the brink of failure, said Paul Zimnisky, an independent diamond industry analyst based in New York.

The industry has been mired in a slump for the past decade. During that time, diamond prices have dropped by a third, driven by a glut on the market, the rise of synthetic diamonds and falling demand.

The COVID-19 pandemic was another body blow. This spring, prices dropped another 10 per cent. At least eight of the world's 50 major diamond mines remain closed due to the health crisis, Zimnisky said.

"They're in Russia, Africa, Canada. This is not something that's unique to Dominion — or Canada, for that matter," he said.

"The most profitable diamond mines will be fine, the weakest may not make it through this, and then there are those in between, maybe on the fringe of profitability.”

Overall, he predicts global diamond production will drop 25 per cent this year, to the lowest level since the Northwest Territories' diamond rush began in the mid-1990s.

What happens next?

When it applied for creditor protection, Dominion owed $150 million to businesses across Canada — $130 million to another branch in its corporate family and the rest to other suppliers and contractors, according to documents filed in court.

In the Northwest Territories, it owes 50 companies a combined $13.2 million, according to a CBC News analysis of its creditor listing.

For Paul Gruner, the CEO of Det'on Cho, the Yellowknives Dene's economic arm and Dominion’s largest northern creditor, it's not the $5 million owed now that keeps him up at night, it's the fear of contracts that won't materialize down the road.

"Is it material? Absolutely," Gruner said of the money owed. "But it's not going to kill us."

As unsecured creditors, payment in full isn't guaranteed. It'll be up to the court process to determine what happens. Though Dominion promises to honour its obligations, Det'on Cho and others could walk away with pennies on the dollar.

"The bigger issue really is longer term," Gruner said. "You've got the one-time hit, but then you have to think, what does this mean for our business over the next 10-15 years?"

In Det'on Cho’s case, it planned for work to continue at Dominion's Ekati mine for the next 10 years. Now, that's up in the air.

Meanwhile, Diavik had already expected to close in 2025, and Gahcho Kué around 2030.

"They're world-class mines, but they're getting older," said Zimnisky, the industry analyst. "Most of the original ore, it's already been mined. That's the nature of mining."

It's a grim prospect, and there are few solid answers for how to proceed.

The territory's budding tourism industry appears decimated by COVID-19 travel restrictions, and though there are proposed mining projects, none are near production, or big enough to fill the hole left by the diamond mines.

"If I look at our business, 80 per cent is related to mining," Gruner said. "There'd be a fraction remaining once those diamond mines have been removed from the equation."

He's calling on the territorial government to reform procurement rules, making it easier for local and Indigenous-led businesses to win government contracts. It wouldn't replace mining, but it'd be a start, he said.

For its part, Dominion pledges to continue operations once its finances are restructured this summer.

On May 22, Washington Diamond Investments, a different subsidiary of The Washington Companies, put in a $126 million US bid to buy Dominion's assets and take responsibility for its debts.

Simply put, this deal is like one member of a family loaning another member money to get through tough times, said Ian Lee, an associate business professor at Carleton University who is familiar with the process and the Dominion case.

A court-supervised bidding process is now underway to see if another buyer will step in.

A spokesperson for The Washington Companies and Dominion CEO Pat Merrin both declined interview requests from CBC News.

Instead, Dominion sent a statement restating its commitment to reopen and its desire to "pay or meet obligations owed to employees, including pension obligations and to remain a significant employer and corporate citizen in the Northwest Territories."

However, lawyers for creditors and Dominion's partners are fighting the proposed Washington Diamonds Investments deal. Lawyers for the creditors holding the $550 million US bond say the deal leaves them with nothing, while lawyers for Dominion’s partner at Diavik say there are serious irregularities with how the proposal is structured, setting up what could be a long, drawn-out court process.

In Ndilo, Yellowknives Dene Chief Ernest Betsina is unsure what the future holds.

His First Nation has signed on to run operations at a planned small-scale rare earths mine on their traditional Akaitcho territory.

He's also calling on the federal and territorial governments to finish ongoing land claims negotiations, which would create certainty and free up land for responsible, sustainable mining in the future, to set up the next economic era in the territories.

"I want us to be involved," Betsina said. "I don't want to see another Giant Mine, where they come in, bulldoze and run over our people."