May 11, 2019

This is the middle chapter of a three-part story about the life, death and legacy of Saskatoon's Capitol movie theatre. Click here for Part 1 and here for Part 3.

In December 1978, word got out that a development company wanted to tear down Saskatoon's Capitol theatre — a 50-year-old movie palace that had also served as the city's cultural centre.

In its place, Edmonton-based Princeton Developments wanted to put a mall and office tower — what residents know today as the Scotia Centre mall on Second Avenue.

Theatre shareholder Jack Byers, whose uncle Newt opened the theatre, was asked for details by the StarPhoenix. “It burns me up,” Byers told the city's newspaper of record. “Everybody wants to know our business.”

MARGARET SYKES (Capitol cleaning lady): [The staff] heard rumours for a long, long time that the theatre was going to be sold, before it ever happened.

BILL SARJEANT (preservationist): The first time I knew anything was happening was when I got a call from the StarPhoenix. By this time, everything started blowing up in all directions. Everybody started getting mad.

DON KERR (preservationist): It was the first heritage fight in Saskatoon that was bloody and intense.

Act Two: "Save The Cap"

Preservationists faced an uphill battle from the start.

The city’s planning and development committee had been offered a chance to buy the Capitol a year before Princeton Developments entered the picture. It turned the deal down without even telling city council about it.

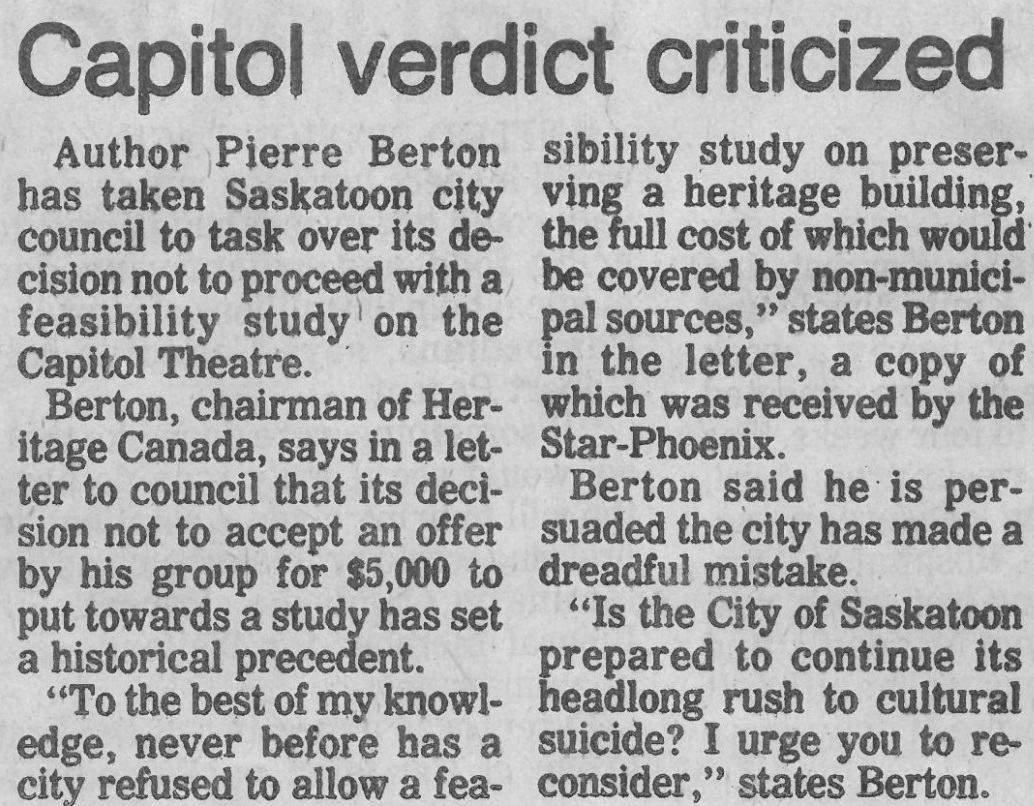

Also rejected: an offer from the province to co-fund a study on whether the theatre could be preserved.

BILL SARJEANT: That’s the most reprehensible thing of all.

DON KERR: That offer also wasn’t reported to council.

PETER ZAKRESKI (city councillor, 1974-1979): I think once you commit yourself to a feasibility study, you're committing yourself to go the next step.

It was a different time when it came to historic preservation. The Saskatoon Heritage Society had only just gotten off the ground, spurred by the destruction of the Norfolk Trust Building.

The Heritage Act of the time only offered protection to provincially-owned buildings.

DON KERR (preservationist): There was no heritage movement at all in the mid-70s. My hope was that [a revised] Heritage Act would come in before the [Capitol] went down, but the provincial government was so incompetent.

BILL DELAINEY (preservationist): The political will wasn't there.

JULIE HARRIS (campaigner): The fight was in essence a class fight. The city could have found a way to save the theatre if they wanted to. But the argument was always that the Capitol couldn’t make money.

BILL SARJEANT: There was a never case where they knew the building was in danger and [councillors] turned around and consulted us.

City councillor Peter Zakreski headed the planning committee at the time. “There was no emotional [connection] for me,” he says of the Capitol. “I’m not saying that others didn't have it. But I did not.”

BILL SARJEANT: Zakreski was not really very helpful to us. Sometimes I think he was downright unhelpful — kept things under covers that should have been out in the open.

PETER ZAKRESKI: Well, that was the process of the day: confidential meetings of planning and development.

PETER ZAKRESKI: The decision not to purchase [the Capitol] was unanimous. The real concern was, “What are you going to do with it if you buy it?” There was a caveat that the building could not be used for a movie theatre. Who's going to use it and what's going to be the ongoing cost to the taxpayer?

ELAINE ZAKRESKI (Peter Zakreski’s wife): I had much more of an emotional attachment to the Capitol and I was wishing there was some way that it could be kept. It probably didn't make any sense [business-wise].

Theatre groups had explored the idea of using the Capitol as a performing arts centre. So the committee did a “crude” crunching of the numbers, according to Zakreski. It would cost the city $1.1 million [in 2019 dollars] just to pay for staff.

MORRIS CHERNESKEY (city councillor, 1970-1994): You’ve got to understand, we were in pre-boom years. We had [TCU Place] with its usual deficits. At the same time we had the Mendel Art Gallery. Same situation. Those things mitigated against it.

Was a 50-year-old movie theatre historic and worth saving? It depended on who you asked.

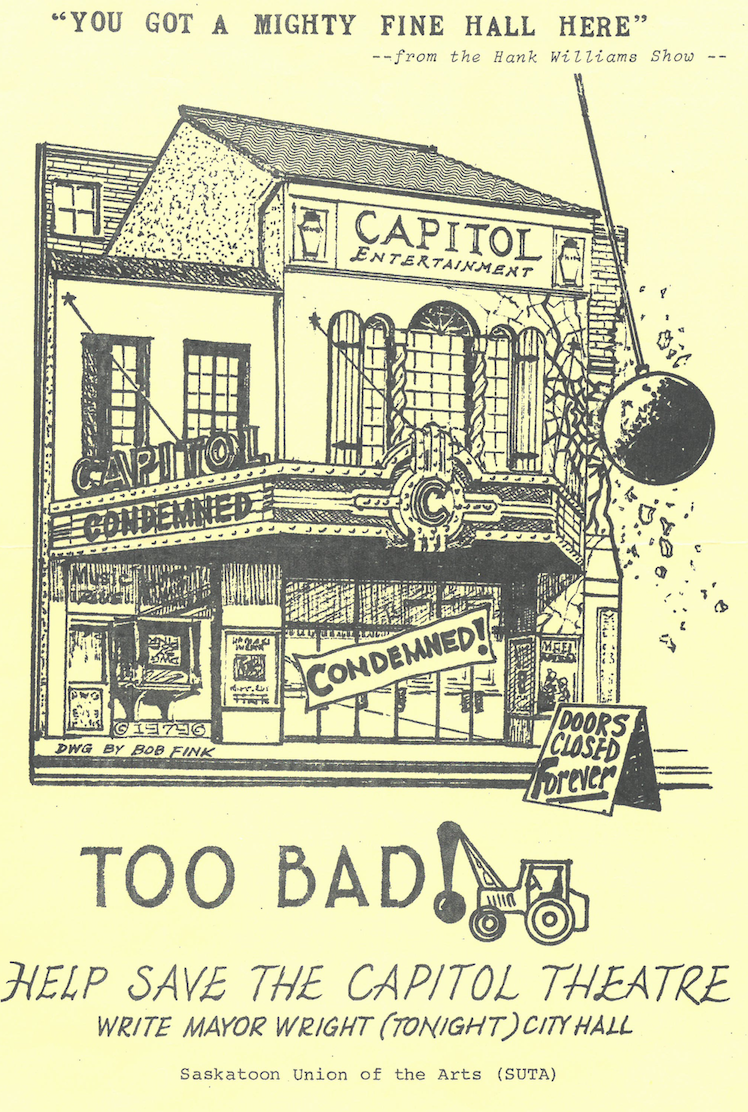

BOB FINK (campaigner): The Capitol Theatre was a heritage building the day it was built because of its beauty, not because of its history. You tell what’s worth saving with your eyes.

HUGH DOUGLAS (moviegoer): If this was not a piece of heritage, I don't know what was.

JULIE HARRIS (campaigner): I thought it was horrendously ugly inside. But I thought it was interesting and unique — a gaudy and overdone theatre.

BILL SARJEANT: I think a city should have a sense of its own life inherent in it by the range of buildings in it. You should see it growing like a house that’s been inhabited a long time, with new areas and new additions but something of the old feeling, to give the city heart and the spirit.

This is all terribly esoteric. I think it does matter but people can say, “Ah, the hell with it.”

John Ferguson was leery of appearing that way. The founder of Princeton Developments, Ferguson actually sat on a heritage board back in Edmonton. He would ultimately see to it that the front facade of the Bank of Nova Scotia, next door to the Capitol, be preserved.

But Ferguson never stepped foot inside the theatre before deciding to buy it.

JOHN FERGUSON: It just never even dawned on me for one minute that it was historical.

I went to see [Mayor Cliff Wright] to say, "What would you do?" He said, "Listen, this thing is just a lot of crap. It's very poor quality. It's not what it appears to be."

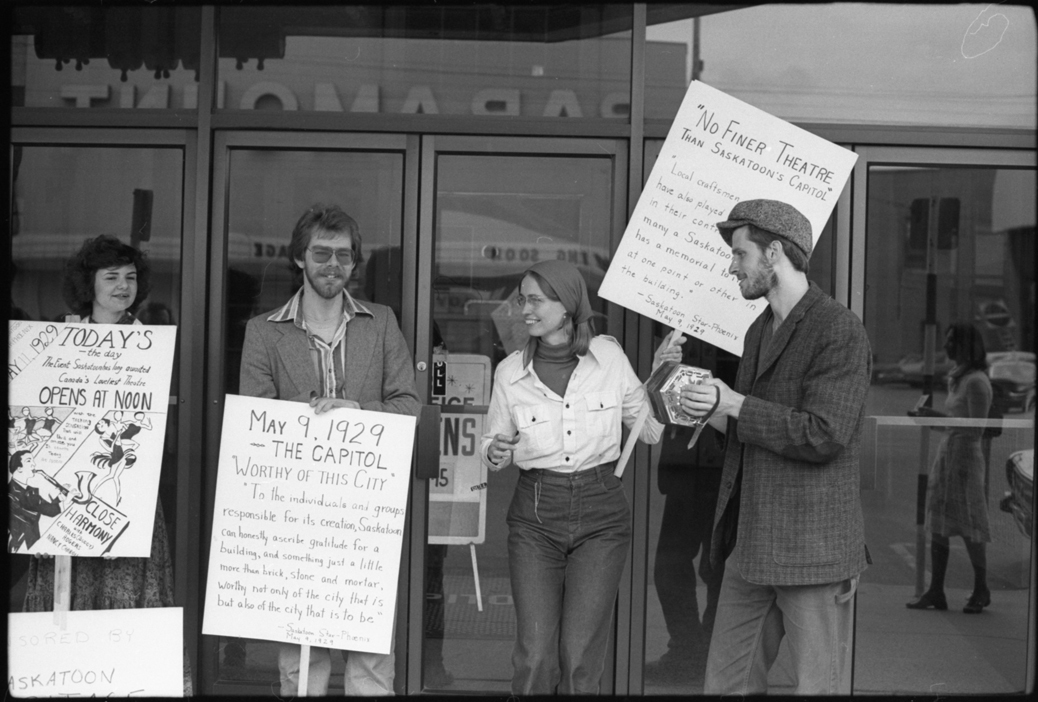

Dec. 1, 1979, was “the magic date.” Ferguson had until then to buy the Capitol property. He met with preservationist Don Kerr months before — around the time the campaign to save the theatre launched with a celebration of the theatre’s 50th birthday.

[Watch the bittersweet celebration below.]

DON KERR: Our main push was to see whether their development [could] include the Capitol theatre. Could they build a great arch over the theatre and build above it?

JOHN FERGUSON: There were impractical architectural ideas. You couldn’t economically, under any basis whatsoever, build above the Capitol.

Things came to a head at City Hall in July 1979.

City council granted Princeton Developments the demolition permit, prompting a last-ditch effort to somehow save the theatre.

There was a 9,000-signature petition, protests in front of the theatre, and even a letter to the StarPhoenix from preeminent Canadian historian Pierre Berton.

BOB FINK (campaigner): There was a discussion on whether to try more radical steps to save the Capitol: sit-ins, militant actions.

JOHN FERGUSON: [Businesspeople would] go so far as to say, “Knock the goddamn thing down before anybody gets onto it, because they may stop you.”

The movie theatre closed quietly. No big to-do on its last day, Nov. 29, 1979, just a business-as-usual ad in the StarPhoenix.

[Watch below: CBC News reports on the Capitol's unceremonious fade-to-black in 1979.]

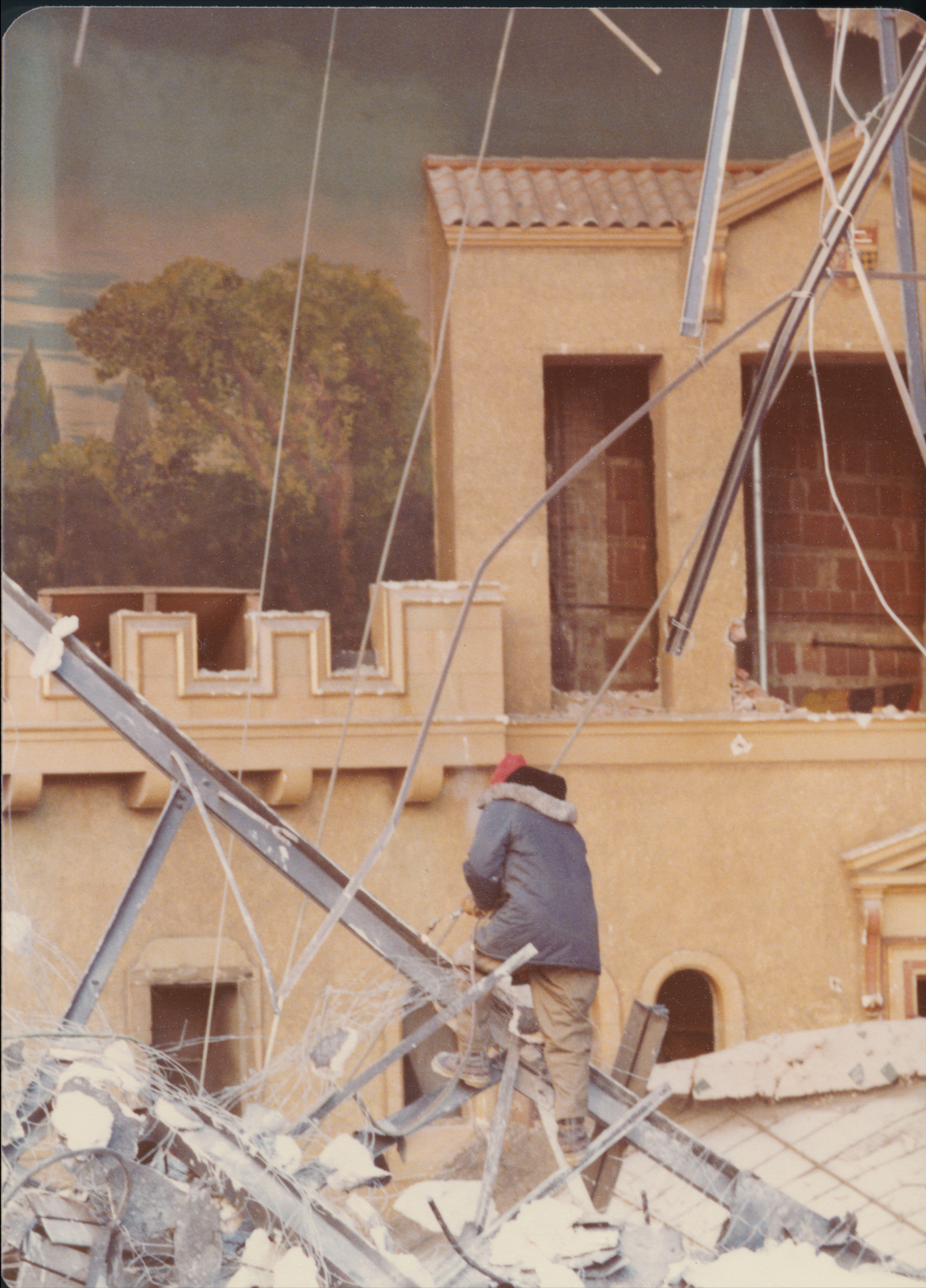

Two days later, the wrecking ball made good on its threat.

City councillor George Taylor had vowed to continue the fight in that day's Saskatoon StarPhoenix.

But long before people had picked up the afternoon paper from their front stoop, the demolition had already begun.

BILL SARJEANT: They really just knocked a hole in it over the weekend to make it irrecoverable.

CLINTON BURLOCK (Capitol staffer, 1970-1979): [Inside], it was all dark. I was tripping over things, couldn’t see anything. A little bit spooky.

KEVIN HOLDSTOCK (Capitol doorman): Clinton and I had to move some boxes out of the way of the wrecking ball. I asked for combat pay that day, but didn’t get it.

MARGARET SYKES (Capitol cleaner): It was just like a disaster area. I guess they were trying to keep it silent.

BOB FINK (campaigner): The developers didn’t want several weeks of salvage to inflame the feelings of the public.

MARK ANDERSON (Western Development Museum conservator): A while ago I met a man who was a teenager or in his early twenties who was headed home the night [of] the demolition. He walked by and actually burst into tears when he saw the bulldozer starting on it. He just loved the theatre so much.

JEFF O'BRIEN (City of Saskatoon archivist): I think they felt betrayed by the whole thing. And there still is a certain amount of residual anger now.

John Ferguson of Princeton Developments said the company had met a week earlier to ponder whether they should hold a press conference to warn the public.

JOHN FERGUSON: My decision was: definitely not. Because … you’re going to have people out there taking pictures. People might even picket and stand in the roads.

MICHAEL TAFT (Capitol theatre oral history interviewer, 1980): A lot of people criticized you for being sneaky.

JOHN FERGUSON: Oh, sure. But I’d rather that than have somebody standing in the road and say, “We’re not moving. Knock it down and see what happens when you injure us.”

I don’t feel the least bit guilty.

Where can you still find pieces of the Cap today? Click here to find out in Act 3, "Scattered Pictures."

Listen below to a short radio documentary version of Act 2 - "Save The Cap."