Feb. 26, 2018. It was the day before Patti Davis's 69th birthday.

Stricken with end-stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, she was lying in the bed of her Halifax home, feeling low, when the phone rang downstairs. Her husband, Bob, answered it.

"He came into the room and mouthed, 'It's Toronto,' and I went, 'Oh my goodness.' And so I took the phone; I was shaking," she says.

The person on the other end cut to the chase: "Patti, we have a set of lungs for you. Can you let us know if you can get on a plane?"

Every year, around two dozen patients from Atlantic Canada receive lung transplants in Toronto. Since the organ survives only a few hours outside the body, recipients have typically moved to the city in order to be close to Toronto General Hospital as they await their match.

It's come at a steep financial cost to them and their families. On average, patients and their support person (often a family member) have had to live in Toronto for six months before the operation, followed by another three during recovery.

But Davis's experience last year marked an extraordinary change. She was the first patient allowed to wait in Halifax — 1,793 kilometres away from the hospital — until a match was found.

It was a risky experiment, made possible by a significant piece of technology that is changing the way lung transplants will be performed across Canada, at least for some patients.

In Toronto, Dr. Shaf Keshavjee has spent years trying to solve the problem of geography and transplants. He is the surgeon-in-chief of the Toronto Lung Transplant Program, considered one of the top programs of its kind in the world.

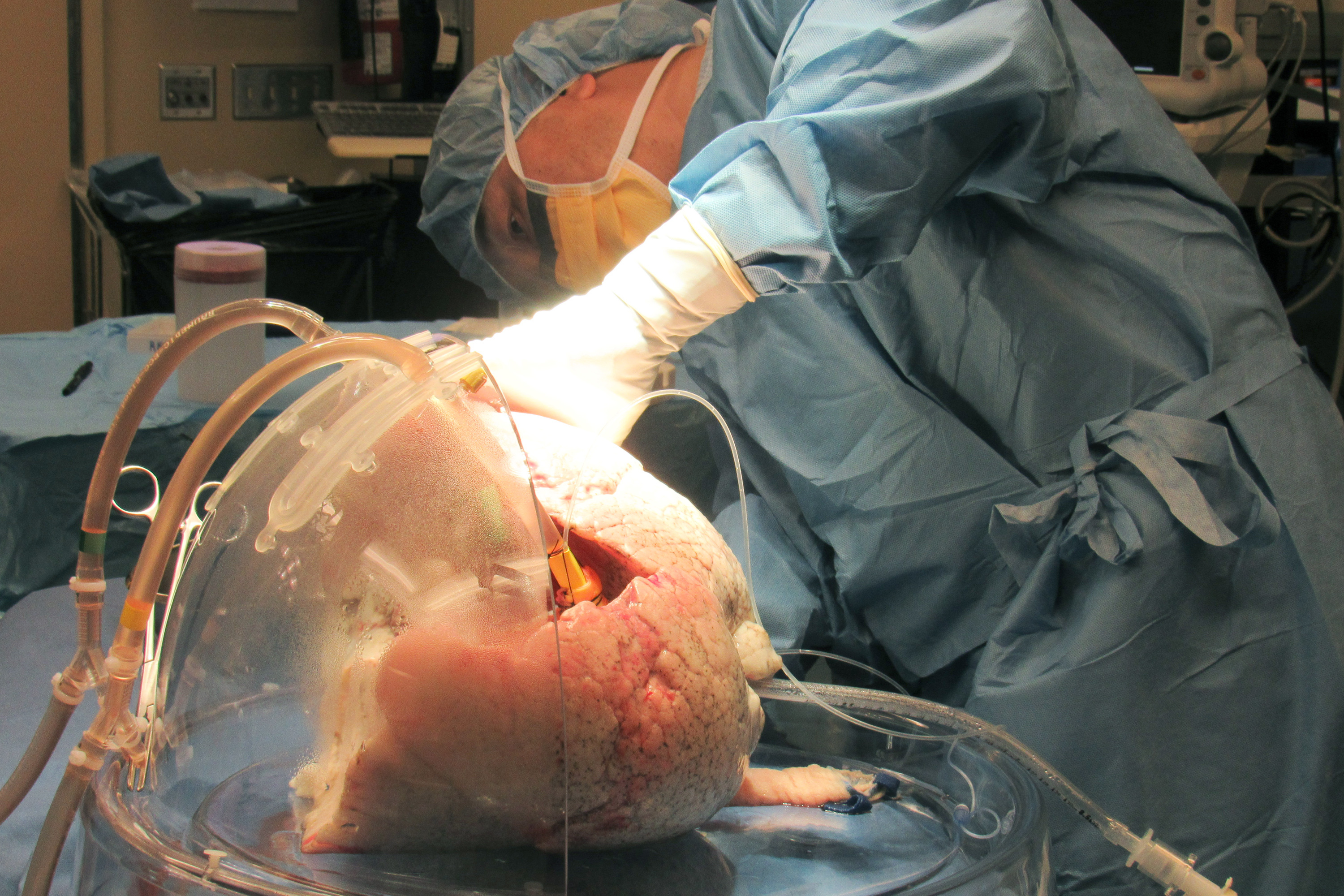

He developed the Ex Vivo Lung Perfusion System (EVLP). The machine looks like an incubator; it holds lungs and keeps them alive between the time of donation and transplant.

Lungs are the most fragile organs, and they were the last of the major organs to be transplanted successfully, Keshavjee points out. Historically, he says, only one in five donations could be used. The remaining lungs were rejected due to infection or other issues.

The new technology has allowed doctors to make major gains, opening the door for them to transplant lungs that were once thought to be unusable.

The EVLP supports lungs while they are tested to make sure they're viable. While outside the body, doctors can even deliver drugs to the organ and treat it for diseases.

Last year, the Toronto team successfully transplanted lungs that had been infected with hepatitis C into 10 patients, who were also put on medication regimes.

Another advantage of the sterile dome is that lungs can live significantly longer outside the body, pushing to as much as 12 hours the window between donation and transplant.

"We actually had the confidence to say that, you know, if there's some delay or a few extra hours that patient won't miss that chance or we won't be increasing the risk of the operation," Keshavjee says.

It's the first step in what Keshavjee says will be the future of lung transplants for patients across the country.

While the sickest will still need to spend months in Toronto awaiting a match (patients use respirators to breath and there are limits to how much oxygen can be brought on an airplane), others will for the first time be allowed to remain at home right up until the moment a match is found.

Lungs are the only organ not transplanted in Halifax. Right now, the government of Nova Scotia says it pays about $223,000 per surgery in Toronto. Setting up a transplant program in province would cost millions of dollars.

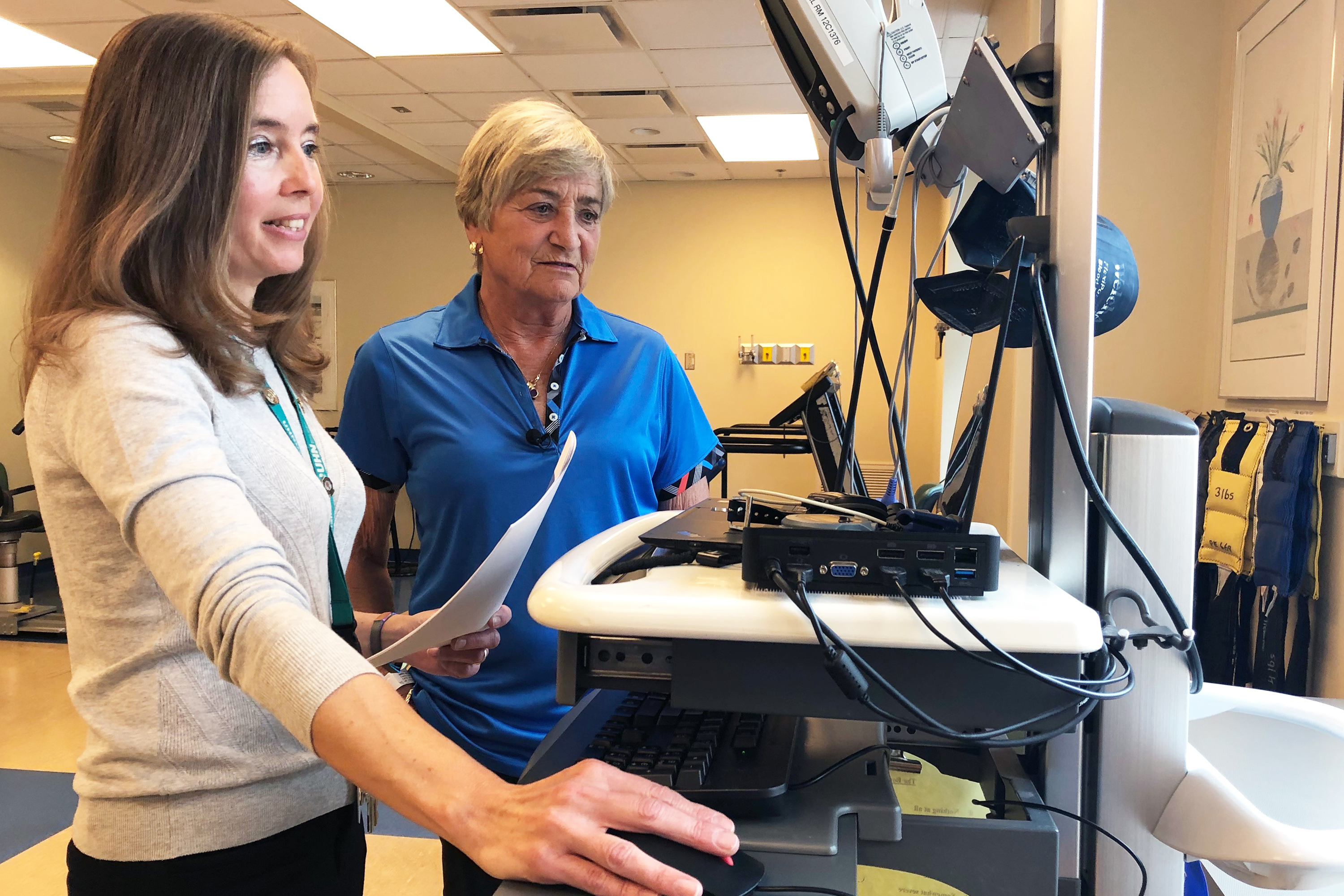

Dr. Meredith Chiasson, a Halifax respirologist, says she's struggled with the financial and emotional stress her patients go through when they leave for Toronto.

"The patients who are the sickest get moved to the front of the line," she says. "So if you're not that sick — sick enough to get a transplant but not that sick that you're getting sicker — you usually wait. So this is the group of patients that we looked at as being the most hard done by."

This year, two of her patients have opted, because of cost, to die instead of having a transplant. Others have sold their houses or liquidated life savings to afford the expense of living in Toronto for months.

Watch this video of lungs in an EVLP breathing outside the human body

Chiasson operates a satellite clinic in Halifax, the first of its kind, for the program at Toronto General Hospital. She works alongside a transplant team based provinces away and does as many tests and exams as possible in Halifax.

With no new money on the table, Chiasson and Keshavjee came up with the Stay at Home pilot program to reduce the costs faced by patients.

After making the medical arrangements, all they needed was a patient to test their plan. The person had to be sick enough for a lung transplant, but healthy enough to be able to board a plane at the last minute.

That's when Patti Davis's name came up.

Davis was presented with the pros and cons. While she would have the ability to stay home, she would have to stay within an hour of an airport and follow a strict exercise regime at the QEII hospital in Halifax.

But if the weather was bad or flights were full, she ran the risk of missing her match.

"I was prepared to take the chance," Davis says. "I jumped at it."

On the day she received the call, Davis and her husband raced to the airport, where they bought the last two available seats on an afternoon flight to Toronto.

"It was such a panic that when we left, our daughter told us that we left all the lights on in the house. The door was wide open. I hadn't even said goodbye to the dog."

Davis's success has now opened the door for more patients to wait in Halifax until they have a match. Three will now be allowed in the Stay at Home program at a time, if they meet the strict health requirements.

Depending on where they’re from, it could save them thousands of dollars and allow them to remain close to their emotional support networks.

"It used to be you had to be within two hours of Toronto, and then as our capabilities grew we went to the four or five, six-hour range, and now you know we have even more capability," Keshevjee says. "The Halifax program is sort of our star program."

With the EVLP and the new ability to treat lungs outside the body, the transplant team now has double the number that are viable. The ex-vivo technique allows doctors to see how the organ performs outside the body. It is supplied with fluid to remove waste and add nutrients, and doctors can perform a scope to check for infection.

It means that lungs that were once considered to be on the fence and subsequently rejected can now be used. Last year, Kesavjee says they completed nearly 200 transplants.

"In the future of transplantation, if we can preserve organs for a long time, everybody can stay at home and we just bring them in when it's time to get a new lung," he says. "That'll be wonderful. And I think we're going to see that."

Not only that, as their techniques change, he believes lung patients will be able to return to their local hospitals or go straight home after being discharged.

Before that day comes, he says there are immediate ways to limit the time patients spend away. He’s calling on the provinces to increase home care, as he says in many cases people are kept longer in hospital in Toronto simply because they don't have support at home.

He also says seamless access to medical charts would mean something as simple as a blood test wouldn’t have to be repeated from province to province.

After her transplant, Patti had to stay in Toronto for three months while she recovered. She estimates that alone cost her between $8,000 and $10,000.

"Which is peanuts compared to those that have to relocate here. So we're very fortunate that way," she says.

She'll never forget that first breath with her new lungs, or how they changed her life.

One year later, she says she has so much to be grateful for: Her donor, their family and the extra time she got to spend at home.

"It was the best birthday present I could ever get. It's like I was reborn. A new life."