September 29, 2021

WARNING: This story contains distressing details.

Even among a list of thousands of names, it stands out — it's hard to swallow.

Dummy Bad Boy.

As First Nations across the country work to uncover unmarked graves at former residential school sites in Canada, one question is at the heart of the effort: Who do they belong to?

A two-month investigation by CBC News sifting through archives helped piece together some of who this one missing student was — and how his outdated and derogatory name ended up on the official record.

"The first thing that comes to my mind is discrimination," said Herman Yellow Old Woman, a member of the Siksika Nation in southern Alberta and the elder-in-residence at the Old Sun Community College.

The name is found among those listed on a memorial by the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation (NCTR) for children who never returned home from residential school.

Other names on that list are incomplete. Some are simply reduced to numbers. But they all have one thing in common: Details of their final resting place are scarce.

Since the spring, several First Nations across the country have found unmarked graves located at former residential schools sites, leading many to re-examine the issue of children who died while attending the schools.

For much of the last century, more than 150,000 First Nations, Métis and Inuit children were forced to attend church-run, government-funded residential schools in Canada.

Separated from their families and stripped of their language and culture, they were sent hundreds of kilometres away, where they were often given new Christian names.

The sole document held by the NCTR reveals little about this student. He was taken more than 900 kilometres away from his family in southern Alberta and died at the Washakada Indian Home in Elkhorn, Man., during the 1890s

The student’s father appears to be named Bad Boy in the record, which was written by the Black Foot Agency Indian agent responsible for First Nations relations in the region at that time.

That family name traces back to the same Blackfoot community where Yellow Old Woman lives.

“Being First Nation, Blackfoot ... from when we were born until the time we crossover, we face discrimination every day,” he said.

“It's very sad," he said. "The fact that this poor young fellow ... was taken from his community and taken far away from home into a strange place.”

The National Student Memorial Register

Established as a repository for residential school archival history, the NCTR holds more than four million records and testimonies gathered by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC).

In 2019, it created the National Student Memorial Register — a response to one of the commission’s calls to action to remember and honour children who died or went missing at these schools.

- Do you know of a child who never came home from residential school? Or someone who worked at one? We would like to hear from you. Email our Indigenous-led team investigating the impacts of residential schools at wherearethey@cbc.ca or call toll-free: 1-833-824-0800.

To date, there are 4,118 children in the registry, including 26 students from the Washakada Indian Home.

In many instances, however, substantial information is missing — like with this student’s file.

According to NCTR senior archivist Jesse Boiteau, it’s a reflection of the colonial records.

More often than not, he said, the death of a child is only mentioned in passing or jotted in a margin of an archival document, reconciling a difficult decision to release certain names.

"Oftentimes, that's the only information that we have to go off of," said Boiteau.

"Regardless of how difficult and how sensitive and how disrespectful it might be to some of these children, keeping that information back would do more harm than making it available — and potentially finding the true identity of the children."

- 'This is heavy truth': Tk'emlúps te Secwépemc chief says more to be done to identify unmarked graves

Life at Washakada

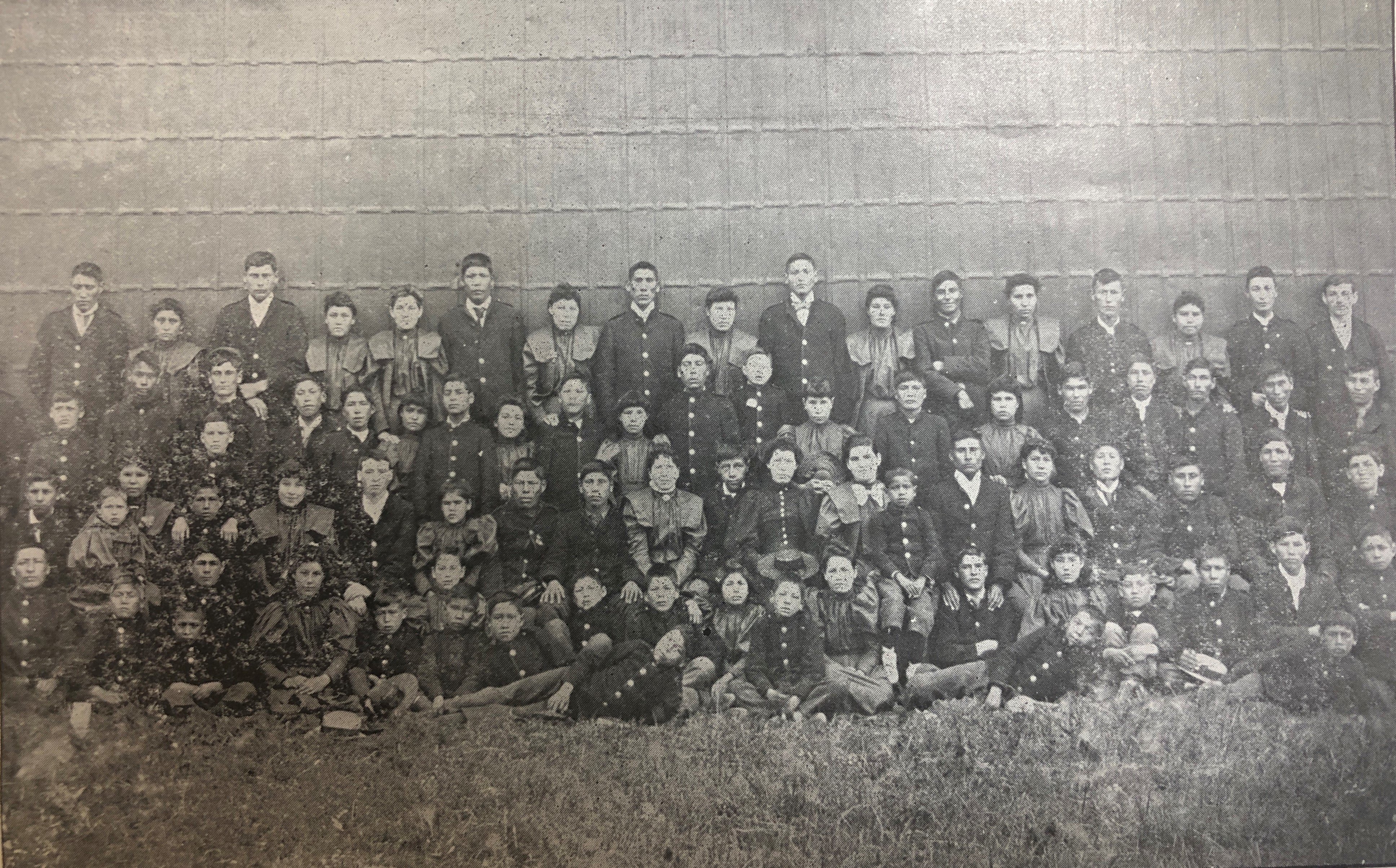

Archival snippets shed some light on what life would've been like for the student at the Washakada Indian Home.

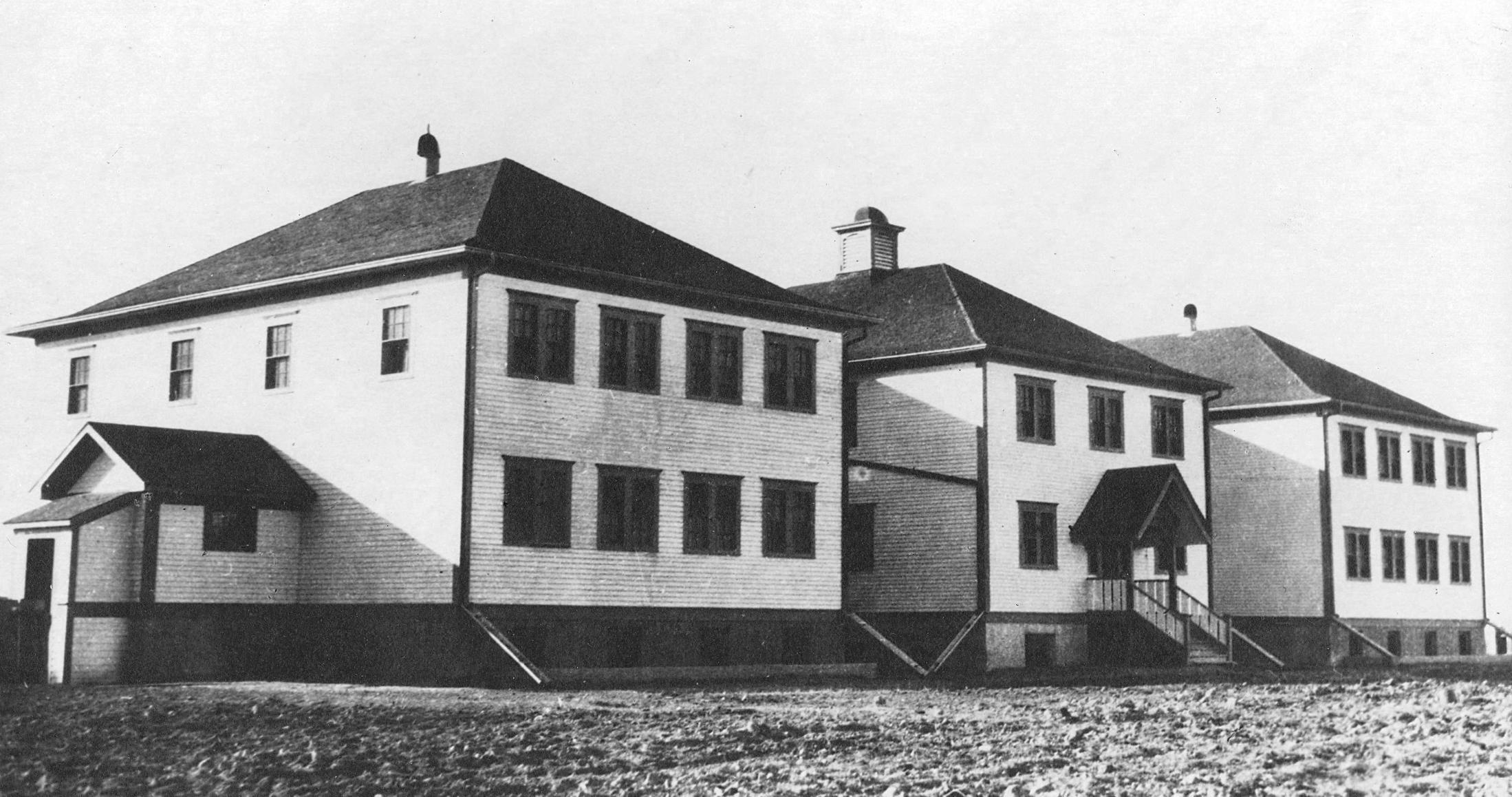

The school was established in the village of Elkhorn, Man., on June 10, 1888, by Anglican missionary Edward Francis Wilson. Wilson named the school after its first donor, George Rowswell whose “Indian” name meant “all that is good.”

The school closed in 1918, though it reopened a few years later as the Elkhorn Residential School under the Anglican Church’s Missionary Society. It was in operation until 1949.

A brief reference in an annual report from the Department of Indian Affairs reveals that this student arrived at the school in 1891 at age 13. His schooling was financially supported by St. Stephen's Sunday School in Montreal.

At the time, residential schools were known as industrial schools, where students split their days in the classroom with laborious farm or tradework.

Boys at Washakada were taught boot-making, printing, tailoring and carpentry. The Washakada Indian Home Printing Office is where the student ended up by 14, learning the art of printing under the instruction of W. J. Thompson.

Equipped with a Gordon job press and a small army newspaper press, he and five other pupils conducted all the mechanical work to print the village’s weekly newspaper, the Elkhorn Advocate.

Nap-ia-mo-kinma

An Indian Affairs annual report from 1895 described the then-17-year-old as "a fine, strong, intelligent lad of fine physique, and is unusually careful of his personal appearance."

It also provided insight where the nickname of Dummy may have come from — an apparent reference to his inability to speak or hear.

"This boy is a marvel, being a deaf-mute," the report reads.

It’s a shock to Yellow Old Woman, but he said that name has been given to more than one child by Indian agents or missionaries in Siksika — as recently as the 1960s.

"I can't imagine living with a name like that," he said. "That would be a lifetime effect on me.”

“It disturbs me to know that the things that he had to go through, especially being physically challenged.”

Even the Bad Boy name is a reflection of discrimination Blackfoot families faced, he said. Due in large part to poor translations, government officials, missionaries and interpreters recorded other families’ names as Not Useful, Drunken Chief, Raw Eater and Ugly.

But CBC News found some documents containing what is believed to be the boy's traditional Blackfoot name: Nap-ia-mo-kinma. Other spellings read Na-pin-o-mo-kin-ma.

A fluent speaker and teacher of the language, Yellow Old Woman, consulting with others, tried to translate the traditional name, though he believes it may be a misinterpretation or misspelling.

“There's several ways that you can interpret at the beginning, but it's the ending that was probably spelled wrong. So we can make a guess,” he said.

“A spirit of male horse is what we can come up with, that sounds close to it ... We don't know what the connection is to his family or his people.”

Death

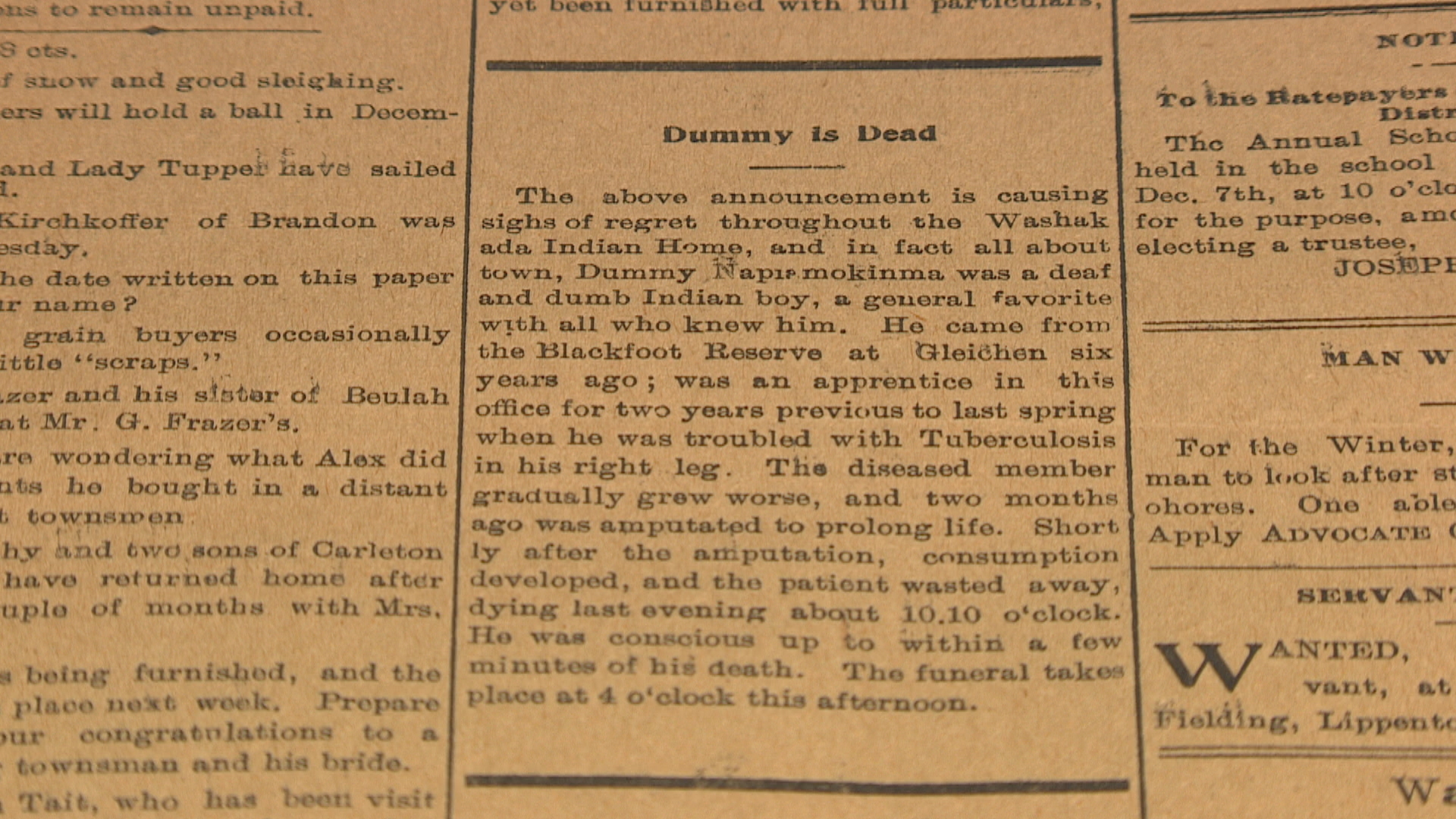

Slightly more is known about how the student died, pieced together through experts from annual reports and clippings from the Elkhorn Advocate.

He was confined to the Brandon Hospital with tuberculosis as of June 30, 1896.

Having infected the knee joint, his right leg was amputated in September of that year in an attempt to prolong his life.

He succumbed to the disease two months later, on Nov 12, 1896, at the age of 18 or 19.

Exacerbated by poor health, safety and nutrition conditions, tuberculosis was the leading cause of death of children who died at residential schools, according to TRC findings.

In the death notice published by the Elkhorn Advocate, he is remembered as "a general favourite for all who knew him."

It also notes that the funeral was held in Elkhorn but gives no indication of where he died or where he may be buried.

(While none of the former sites of the Washakada school have been searched recently with ground-penetrating radar, some students are believed to be buried in a small Elkhorn cemetery without identifiable grave markers.)

It was not uncommon that children would be sent to tuberculosis sanitariums or hospitals for experimental treatments, Boiteau said, which adds to the list of possibilities of where missing Indigenous children may be buried.

And while snippets of this student’s life can be found through the lens of government documents, Boiteau also cautioned it should be read with a grain of salt.

When it came to reporting or taking photos of the students' experience, records are good examples of propaganda that came out of the residential schools, Boiteau said.

"The Indian agents, the principals, the administrators … would try to paint a very rosy picture to attract more students, to get more funding from the government,” he said.

“What we hear from these survivors is a very contrasting experience from what is written in the official record.”

The reality of Dummy Bad Boy's experiences may never be known.

Archival work continues

The NCTR says it's going to update its register to reflect the new information uncovered about this student, marking the first time a name has completely changed on the public memorial.

And work is ongoing to help restore dignity to children who died at residential schools, said Boiteau, noting it won’t happen overnight.

"We know there are large gaps within the records that we currently hold," he said.

The centre has thousands of archives and survivor testimonies to sift through to identify more children, as well as to fill in missing information for those already identified — a process that Boiteau says will continue as new documents are received.

"We recognize that this work will take generations," said Boiteau. "It didn't happen overnight, and it's going to take years and years and a lot of engagement with survivors, their families, their communities to ensure that those community narratives make their way into the archives."

Support is available for anyone affected by their experience at residential schools and those who are triggered by these reports.

A national Indian Residential School Crisis Line has been set up to provide support for residential school survivors and others affected. People can access emotional and crisis referral services by calling the 24-hour national crisis line: 1-866-925-4419.