On the list of Montreal’s notable neighbourhoods, Bridge-Bonaventure ranks near the bottom.

It’s the largely industrial area most people pass through on their way to Costco or to get onto the Victoria Bridge. But 60 years ago, it was a lively place, home to waves of immigrants who lived in the cramped, two-storey homes that lined the streets and worked in nearby railyards and factories.

Goose Village, or Victoriatown — the names were used interchangeably — was destroyed in the early 1960s, razed in the name of chasing modernity. It hasn’t been an actual neighbourhood since. But change is on the horizon.

Last week, dozens of groups, individuals and business leaders shared their ideas about what should happen to the 2.3-square-kilometre area over four days of hearings by Montreal’s public consultation office (OCPM).

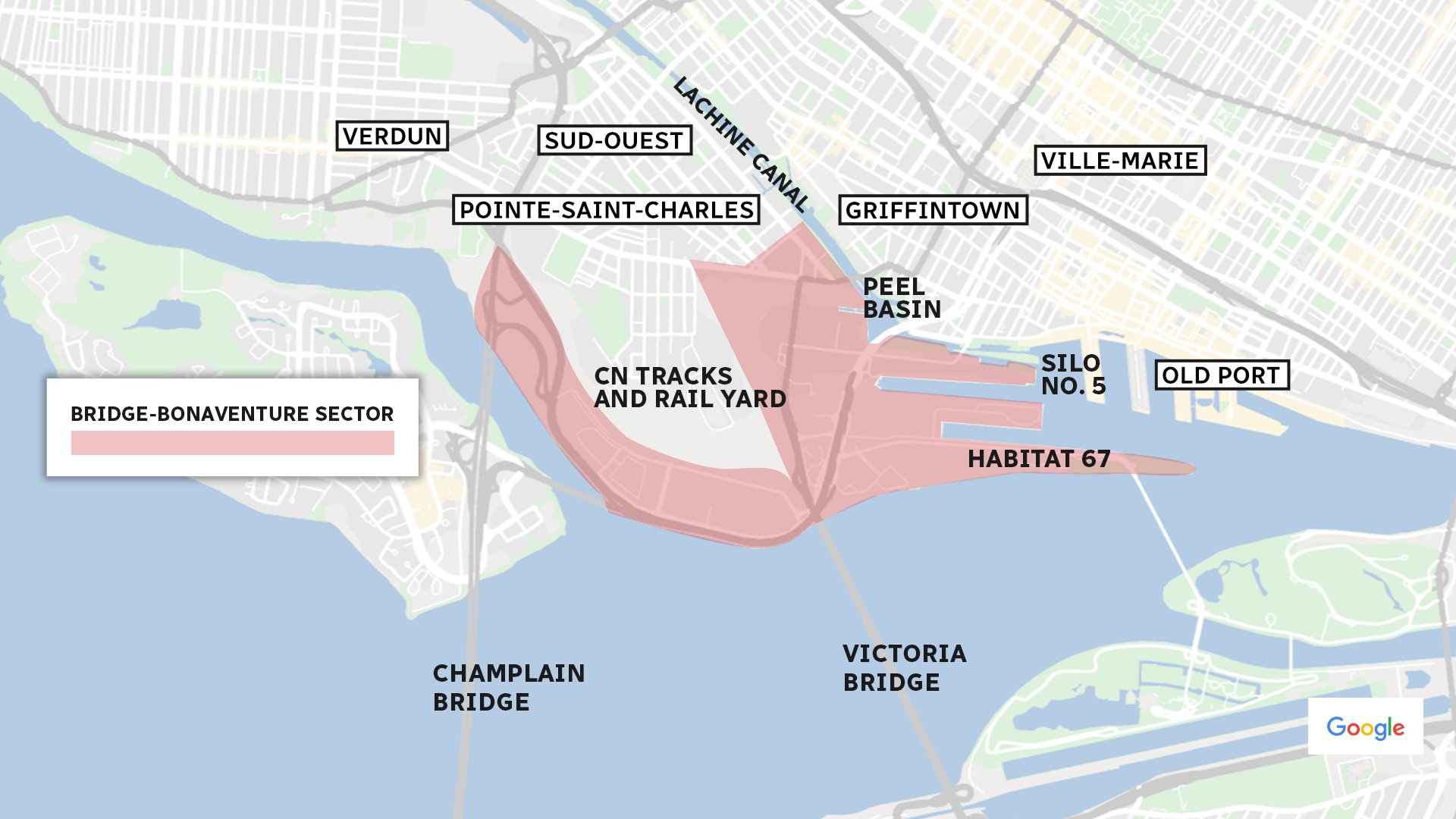

Early next year, the OCPM expects to issue its recommendations on the future of the district, which stretches from the Bonaventure Expressway to the Champlain Bridge, bounded by the St. Lawrence River to the south and the Lachine Canal to the north.

The battle lines have been drawn. On one side, there are those who want to attract new businesses, new residents, and a new baseball team to the area. On the other side, there are those who are already suffering the effects of gentrification in their community, who want to create a neighbourhood that will benefit the people who already live there.

They are all after one thing — revitalization. But that means something different to everyone.

Boom and bust

The Industrial Revolution was good to southwestern Montreal: located near the Lachine Canal and rail lines, it became the hub of industry. People who moved into homes nearby walked to and from work every day.

In the 1960s, Goose Village — bordered by Mill, Bridge and Riverside streets — was poor but teeming with people. About half were Italian immigrants. The rest were English, Irish and French.

In 1962, Montreal was named host of Expo 67, and then-mayor Jean Drapeau wanted to build a stadium where big events could be held. The city steamrolled over Goose Village and built the stadium there. Many of the 1,500 residents forced to leave moved to nearby Pointe-Saint-Charles.

By then, the St. Lawrence Seaway, which had opened to great fanfare in 1959, had supplanted the Lachine Canal as the route toward the Great Lakes. The factories along the canal were closing. The neighbourhood was in decline.

For close to two decades, the canal was little more than a derelict and abandoned sewer. Then, in the late 1970s, Parks Canada took it over, built a bike path and reclaimed it as a park. People of means started wanting to live nearby. The old factories on either side of the waterway were slowly converted to condos — a process that picked up as the century came to an end.

In the early 1990s, the area around St-Patrick and Wellington streets began attracting new industries, harkening back to its roots.

And that stadium? The Autostade hosted events for Expo and served as the home of the Montreal Alouettes before it, in turn was demolished in the 1970s. In 1976, the Als moved into the brand-new Olympic Stadium.

A community, threatened

Some residents of Pointe-Saint-Charles believe plans for another stadium are threatening their neighbourhood anew.

Stephen Bronfman, who heads the group trying to bring baseball back to Montreal, wants to build a new ballpark in the Bridge-Bonaventure district, on federally owned land just south of the Peel Basin.

Last month, protesters showed up at the site, taking turns smashing a baseball-shaped piñata, filled with little plastic houses.

New projects on that land “should improve the lives of everyone who lives there,” said Karine Triollet, a Pointe resident who is spokesperson for Action-Gardien, a coalition of community groups in a hard-scrabble neighbourhood with a history of community activism.

“It’s land that was paid for with taxpayer dollars. We can’t see taxpayer money used for private interests,” said Hassan El Asri, a social housing activist.

Triollet and her colleague Cédric Glorioso-Deraiche were among those who presented their views at the OCPM public consultations.

The plan they put forward is the result of months of consultation with people in Pointe-Saint-Charles.

They want to build social and affordable housing, a high school, a trade school and a multisport field, to give people in the community access to the river. They want to create jobs that meet local needs.

What they don’t want in their neighbourhood is a project that is poorly planned, and they don’t want to be overrun by condo buildings that would do nothing to curb housing shortages — basically, they don’t want to see another Griffintown.

The city estimates it will cost $309 million and take until 2030 to add parks and other green spaces and rearrange roads in Griffintown, details that weren’t considered when that condo boom began.

Concordia University history Prof. Steven High said there is lots at stake: Either Bridge-Bonaventure becomes a model mixed-income community, or it becomes an extension of Griffintown — and another chapter in the area’s history of displacement.

“People are being forced from their homes. We see it with increasing property taxes, people with fixed incomes who inherited their houses and are having a hard time staying in them, people who rent, who are not in social housing, having a hard time staying put,” he said.

“The impact is massive.”

Mayor Valérie Plante’s administration has acknowledged that there are lessons to be learned from how Griffintown came to be. She has also said she is open to the stadium project, as long as that project takes into account the needs and reality of the area.

Of buildings and baseball

For all the talk about a baseball stadium, it’s easy to forget that Montreal still doesn’t have a baseball team.

Bronfman has said he won’t build a stadium before he has a team to play in it, and it’s not easy to land a team these days.

Montreal has been on Major League Baseball’s radar for a while. Earlier this year, one of the most significant developments in the file came to light — the league granted Rays owner Stu Sternberg permission to look into having the team play half its home games in Montreal.

The team, however, is contractually obligated to stay in its home stadium in St. Petersburg until 2027. It needs permission from that city to even start talking about leaving — permission that city’s mayor has not granted. Some say the whole thing is just a ploy to put pressure on local authorities to build the Rays a new stadium in the Tampa area.

From what’s been said publicly, bringing baseball back to Montreal isn’t exactly a fait accompli.

Still, to get a baseball team, Bronfman needs a baseball stadium. Even before the Expos left in 2004, the prevailing wisdom was that a downtown stadium, built specifically for baseball, is what the sport must have to thrive in the city.

Bronfman believes the land near the Peel Basin is the perfect spot for a stadium.

“I think it could add so much to our downtown, to our city, to everything that we stand for,” he said at the hearings.

The location is close to downtown, and maybe most importantly, it will be just south of a stop on the light rail system (REM), which would connect it to people all over the greater Montreal area once it’s up and running by 2023.

This is where Serge Goulet comes in.

Goulet is president of the real-estate development agency Devimco. His company is behind District Griffin, the project that “launched the revival of Griffintown,” according to its website.

Invoking the area’s industrial past, he said he wants to create a world-class hub for clean technology, bringing new jobs to the area.

He said the project would surpass the city’s requirements for family-sized, affordable and subsidized social housing. The coming of the REM offers an opportunity “to create a more diverse, vibrant, dynamic and sustainable living environment,” according to the brief Devimco submitted to the OCPM.

Goulet made his pitch to the OCPM on Oct. 3, hours before Bronfman’s, and he didn’t mention Bronfman, or baseball, once. But the pair is working together.

They want in on a trend that is taking over how sports stadiums are built.

Teams across the United States are working with developers to build neighbourhoods complete with hotels, restaurants, retail, parks, plazas — anchored by a sports stadium.

The idea is to create a destination that can appeal to fans and non-fans alike, that isn’t only buzzing on game days. And the teams make money on the development.

That’s why Concordia Prof. Steven High sees the stadium debate as a harbinger.

“My concern is that the baseball stadium is only the tip of the iceberg. It's really around the condo developments that pay for that stadium,” he said.

Reconciling conflicting visions

The presentations before the OCPM weren’t all baseball versus community housing. A non-profit organization of blacksmiths wants to create a neighbourhood that would play up the history of the area, with stores and workshops for local artisans and industries.

Another group wants to build an Irish cultural centre at the site. It would feature grass fields on which to play rugby and hurling.

The OCPM commissioners now have to come up with their recommendations to the city. They dropped clues about where their heads were at the public meetings — each baseball-related presentation was met with questions about how they plan to get thousands of people to and from a stadium in an already-cramped neighbourhood, and what the stadium will bring the community.

The city isn’t bound by the OCPM’s recommendations, and ultimately, it holds the power to grant the necessary permits and pass zoning changes that would be needed to bring any proposal to fruition.

The city also has right of first refusal on the land where Bronfman and his group want to build the stadium, meaning it could buy the property at the same price offered by an eventual buyer.

Bronfman says the baseball stadium would instill a sense of pride in the people who live there — and that there will be enough affordable and social housing built in the area to meet people’s needs.

“I think with a project like this, because we’ve seen this in many cities, where a stadium like this … brings so many economic benefits, it creates a new hope in areas that are sometimes a little disadvantaged,” he said.

Thing is, the people who already live in the area don’t think the stadium will create new hope or help those who are disadvantaged.

The OCPM will have to figure out how — and whether — the two visions can be reconciled. Its report will be submitted to the city by early 2020.