Jenny Kaastra’s morning routine is nothing out of the ordinary.

She’ll start the day by first moving her two cats off her bed, brushing her teeth, getting dressed, packing up and driving out of her rural Mission, B.C., home at around 8 a.m.

Kaastra, 53, works three jobs as a care worker, working part-time for a private company, a contractor hired by Fraser Health, and for an independent client.

Juggling these jobs keeps her busy. Kaastra works up to 11 to 17 straight days before she gets a day off.

“It can get to you. Mentally. Physically. Emotionally.”

Kaastra is not alone.

About 10,000 people work as care aides in the province. She’s among the 75 per cent who work casual and part-time, according to a June 2019 report from B.C.’s Office of the Seniors Advocate.

As B.C.’s senior population has grown, so has the demand for home support and the chance to live independently at home.

However, according to the report, the workers who provide this care face lower rates of pay relative to other care aide positions and the lowest percentage of full-time positions compared to any other health care occupation.

As Kaastra gets older, she says there are extra bills to pay. She doesn’t have benefits so she pays for things like medication out of pocket, which can cost hundreds of dollars a month.

“It’s a lot of money you have to fork out,” she says in the car on the way to her client.

“[But] if you don't [buy the medication] then you'll be on the other side where you need the care aide to come and see you.”

Kaastra takes her eyes off the road for a split second to pause, then laughs.

“I’m not there yet.”

At around 8:30 a.m. Kaastra pulls into the driveway of her first private client of the day, Rolf-dieter Klose, 95, who lives in a ranch-style bungalow in Abbotsford.

She’s scheduled to work for two hours here.

She makes Klose’s favourite breakfast, a boiled egg and toast. She also does laundry, washes dishes and prepares his lunch. She’ll be back later this evening for another two hours around dinner time.

Kaastra’s work isn’t limited to these household tasks. She’s an important social connection to clients who would otherwise spend their entire day alone.

But it can be tough.

Earlier this year, Kaastra’s partner died of leukemia.

She says she would like to attend a support group for widows but there is too much on her plate.

Kaastra says grieving while providing care to her clients makes her feel like a “chameleon.”

“Like my mom said, you go into one place and you shut off your personal emotions. And you deal with [your client],” she says.

Kaastra's car is the only private space where she can turn off between clients.

“Depending on how long of a drive, you can have a cry, you can have no cries, or you can have happy thoughts.”

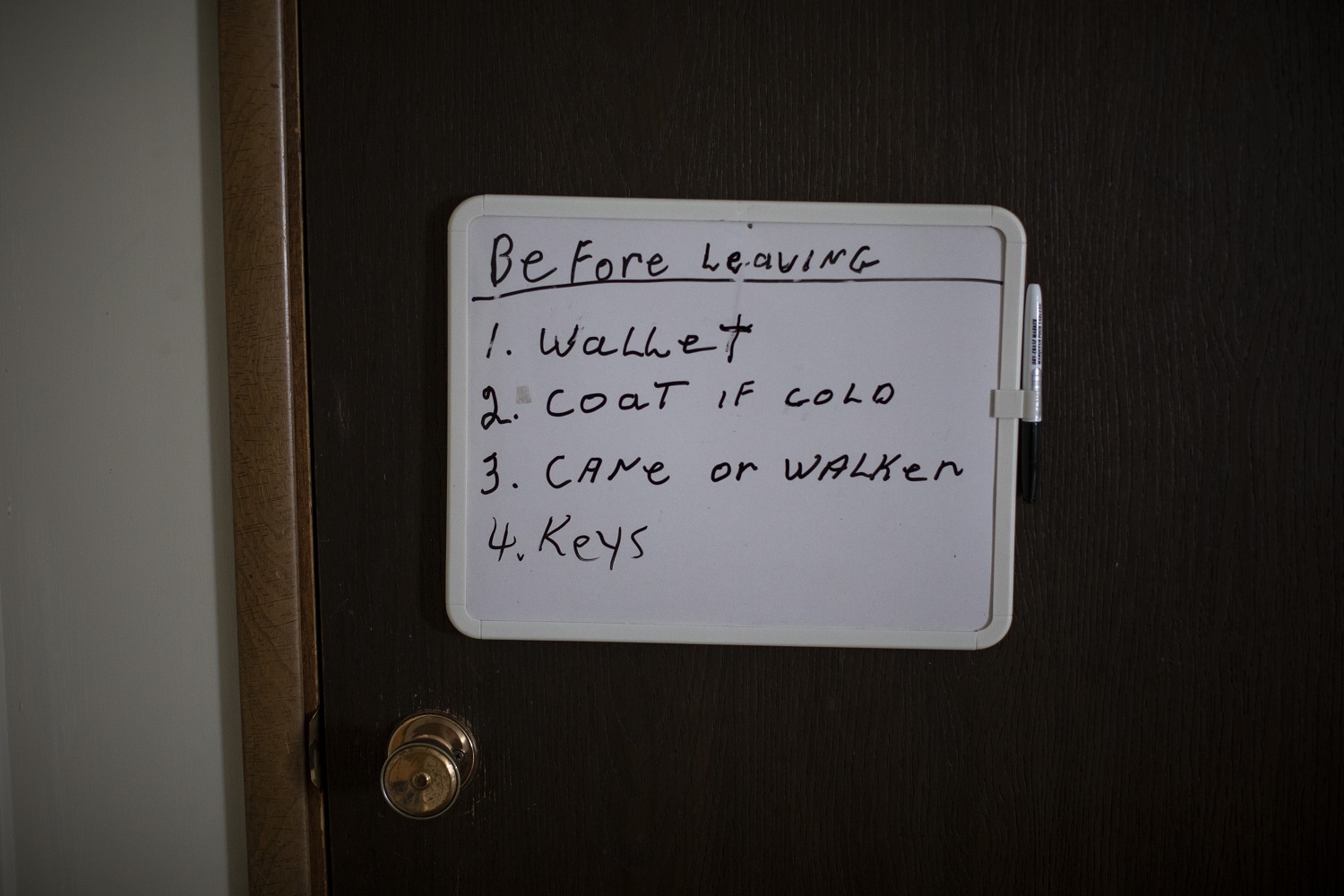

At her next client’s apartment in Maple Ridge, Kaastra is welcomed with a warm smile from Marie Reiu, a retired interior designer.

Reiu, 75, a blonde with a short bob, has recently put in a new set of eyelash extensions.

‘You look good,” Kaastra says to her.

The two women fall into easy conversation as Kaastra sets up the vacuum. They chat about hair and physical appearances and how best to decorate Rieu’s apartment.

The two women share a unique bond.

Reiu’s husband of 47 years died about five years ago. So while Kaastra takes care of Reiu, the older woman takes care of Kaastra, passing down advice on how she can grieve and move on.

“Jenny and people like her are wonderful. I wouldn't be in as good shape as I am now without them,” says Reiu.

As demand for home care increases, the B.C. Care Providers Association (BCCPA) says the province is not prepared for this increased demand.

In a 2018 report, it says B.C. is short about 2,800 caregivers for seniors in assisted living and home health care.

Staffing shortages have been exacerbated by high levels of care-worker burnout, retirements, and injuries on the job.

Both the BCCPA and the Seniors Advocate have some suggestions for change.

The BCCPA wants the government to forgive student loans and reduce barriers for international students to enter the profession.

The Seniors Advocate says the health authorities should improve incentives for care workers including: paid training, increased compensation, and opportunities for stable part-time as well as full-time positions.

There are moments throughout the day where Kaastra feels the pressure of a lack of staffing.

Earlier in the day, leaving Klose’s home, she said felt exhausted. She was unexpectedly behind schedule because the workers before her were not able to attend to some of the chores — which made her list of duties longer.

“[They] just need to hire more people,” she said.

After Kaastra finishes dusting Reiu’s kitchen ceiling lights, it’s time to leave.

It’s raining and she makes a run for her car. Once inside, she reaches to the backseat and pulls a slice of pizza from a 7-Eleven box, which sits among binders, piles of paper and other snacks.

Kaastra's shift will total 12 hours. She still has another five clients to care for.

“It's like you race to get home sometimes, and when you do it's like you're still not done. You've gotta do your own routine,” she says.

“And then you just flop on the bed and go off.”

Until the next morning.

This story is part of Taking Care, a week-long radio series exploring the challenges facing care workers. The series ran Sept. 16 to 20 on CBC Radio One's afternoon shows in B.C. and is part of the Langara University Read-Mercer Fellowship.