June 18, 2018

Even when the pain in her spine made it hard to breathe, Marwa Harb continued to walk to school.

It was 15 minutes each way down a refugee-camp road carved out of the Jordanian desert. Some days, when the ache settled in her chest like a weight, she sat down at the edge of the road to rest.

Doctors at the Zaatari refugee camp told Marwa walking to school was dangerous — her spine was severely curved and the exertion made her heart feel like it was being crushed. They told her not to go.

She didn’t listen.

“I start to walk to school because I don’t want to miss anything,” says the 16-year-old. “I love to study.”

After a month of walking, UNICEF gave Marwa a bulky wheelchair ill-suited for makeshift roads. A friend pushed her to school.

She wasn’t the only one in the family who had trouble walking — Marwa’s father, Mohammad, was also in a wheelchair, as was her 14-year-old brother, Maher. All suffered from a seemingly mysterious affliction. Doctors who treated them had frustratingly little insight.

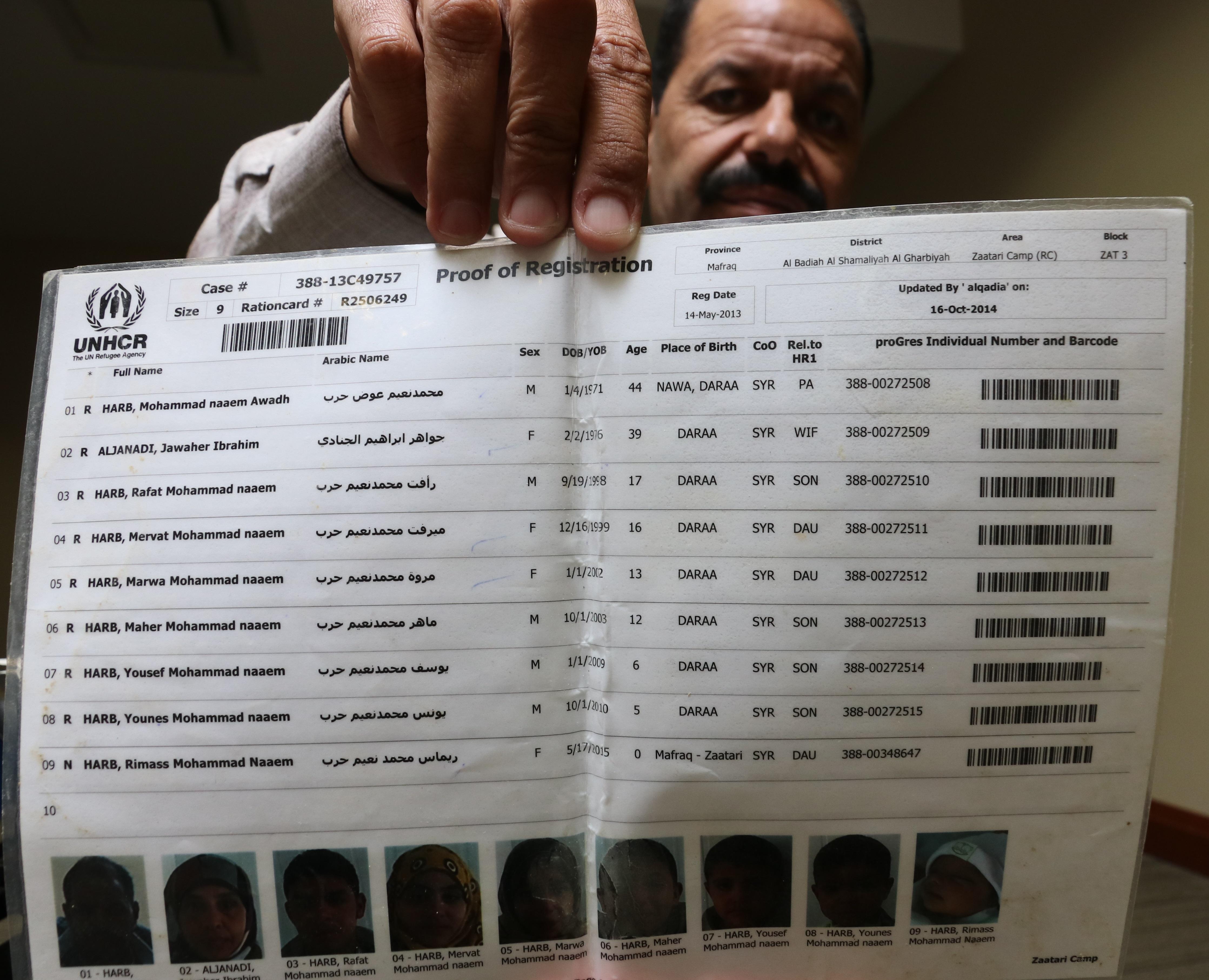

It wasn’t until the Harb family came to Canada two years ago that they could put a name to it: muscular dystrophy. A genetic disease that slowly weakens the muscles, the condition affects half of the members of this family of 10, including three-year-old Rimass and 18-month-old Mias.

The Harb family’s story is part of a little-discussed reality: Many Syrian refugees arrive in Canada with chronic conditions and disabilities that have gone untreated for years.

Like other refugees, Marwa, Mohammad and Maher Harb have been eager to start life in Canada — to go to school, find work, learn a new language. But they must also contend with doctors appointments and surgeries; even leaving their apartment is a trial.

The Harbs live in an 11-storey brown building in west-end Halifax, on the edge of a neighbourhood full of former military homes. The apartment complex is bordered by the end of a CN rail line and a busy commuter thoroughfare.

The 10 family members are crammed into four bedrooms that span two adjoining apartments on the ground floor. The narrow hallway into the main living space is just wide enough for a wheelchair.

Mohammad has contacted a handful of landlords on Kijiji looking for a bigger, more accessible apartment. But he admits that when they ask how many kids he has, the conversation ends.

It’s a "problem for my family, very big problem,” Mohammad says, gesturing to the living room, where a recliner and three couches are pressed against two walls. “You know, three wheelchairs difficult to move together.”

On the living room walls hang colourful paintings of flowers as well as artwork the younger kids have brought home from preschool.

There are no pictures in the narrow hallway. The only accent on the beige wall is at the bottom, just inches from the carpet — black smudges where wheelchairs have scraped against the paint. (In one place, there’s a fist-sized hole, the result of an accidental ramming.)

Mohammad, 47, has lived with a disability for as long as he can remember. Growing up in Nawa, a city of roughly 58,000 people approximately 90 kilometres southwest of Damascus, he had trouble walking and started using a leg brace at age 10.

As a young adult, he spent his spare time writing plays with his friends, a passion he’s passed on to his children.

Mohammad graduated from Damascus University in 1992 with a degree in architecture but there was little work in his field, so he spent two decades managing a grocery store.

His wife, Jawaher Aljanadi, also a graduate of Damascus University, taught high school math in Syria and later in Jordan.

In May 2013, a couple years into the civil war, the Harbs fled their large three-bedroom home in downtown Nawa after a nearby building was blown to pieces, showering the street with thousands of bits of shrapnel the size of fingertips.

“I think my home is broken over my head,” says Mohammad. “I said, ‘I want to leave my country. I can’t live here.’”

By the time he and his family arrived in the Zataari camp in Jordan, he was lacing silk through the brace — the same one he'd had since childhood — to keep it from falling apart. In the camp, Mohammad asked for a new brace. Instead, he got a manual wheelchair, because it was cheaper. It was a fateful decision. His body would never again adjust to walking.

For three years, Mohammad used a wheelchair to get around the Zataari camp. His oldest son, Rafat — now 19 — stayed away from school so he could push his father.

His only reprieve came in the final months, when Mohammad tinkered his way to building a battery-powered bicycle that would carry his chair.

The most neglected people at refugee camps include those with chronic conditions and disabilities, says Dr. Paul Caulford, a family physician with the Canadian Centre for Refugee and Immigrant Health Care in Scarborough, Ont.

“When I looked at chronic diseases on the journeys …. the literature was very clear that the refugee camps and the routes are very poorly equipped to deal with the chronic diseases, and that’s why they are growing,” Caulford says.

The issue is that refugee camps are overrun with what seem like more pressing problems, such as bullet wounds and foot infections.

It means that by the time a patient with a chronic condition is finally seen by a doctor in Canada, their health issues can be incredibly complex, according to Dr. Tim Holland, a family physician with the Newcomer Health Clinic in Halifax.

He calls "under-identified" and under-treated chronic conditions the major health problem his clinic sees.

"You wish you could go back in time and give the appropriate treatment, because you know the patient would be better off," he says.

After three years in Jordan, the Harbs landed at Halifax airport as government-sponsored refugees in February 2016. A doctor visited them at the Best Western Hotel the first week they were there.

Soon after, doctors diagnosed Marwa, Mohammad, Maher, Rimass and Mias with muscular dystrophy, and told the family Marwa's condition had worsened — she needed surgery, and quick.

Muscular dystrophy refers to a host of rare genetic disorders, where an abnormal gene gets in the way of the body’s ability to produce healthy proteins that build muscle. Thousands of Canadians have it. Over time, the muscles deteriorate and a person’s ability to walk, talk and breathe can be stripped away.

"When I came to here, it start to hurt most of the time," Marwa says. "They said, ‘Fast we can, we need to make a surgery for you. Maybe it's not working, but we have to try.’"

The surgery took place at the IWK Health Centre in November 2016. Marwa held on to her weeping mother before being wheeled into the operating room.

“I said, like, inside, to myself… ‘There will be no stop me. I will continue,’” Marwa recalls. “I pray to God, and... my mom was praying to me, and my dad beside me.”

After nine hours, the surgery had to be interrupted. The machines that helped Marwa breathe were taking their toll, and she needed to rest. Marwa spent a week in the intensive-care unit with tape covering the incision in her neck and back. Mohammad slept every night beside her. “I was nervous. It was very difficult. Not easy,” he says.

A week later, surgery resumed. After another nine hours in the operating room, it was over — but the months of recovery were just beginning.

Marwa now has two pill bottles next to her bed for the medication she takes twice a day. She gets dizzy and short of breath, but she has the freedom to move thanks to her motorized wheelchair.

She’s still learning to drive it, and moves cautiously around the apartment. Her left fingers gently lean on the chair’s joystick, which is topped with a pink golf ball.

“At home a lot of accidents in the wheelchair, and in school, too,” she says, chuckling. “Sometimes I drive on [people’s] toes, and I say I am sorry!”

The motorized wheelchairs make moving through the world a little easier. But as with hundreds of thousands of disabled Canadians, simple barriers remain.

Mohammad, Marwa and Maher can’t get out of the apartment without help. There are four doors between them and the outdoors, and none have automatic wheelchair buttons.

It’s a common problem, says Sara Abdo, a disability support co-ordinator with Immigrant Services Association of Nova Scotia, who says all of her 80 clients with disabilities lack suitable housing. They can’t afford anything better.

"Many individuals are living in apartment buildings that are older, that don't have the simple kind of ramp that's to code, that don't have the buttons to help open the door, that don't have physical space for their electric wheelchairs to turn [in]," Abdo says.

In the Harb household, mornings and evenings are spent dropping off and picking up kids from school.

On a recent Friday afternoon, Mohammad prepared to pick up his youngest son, Mias, from preschool.

Mohammad drove his large black accessible van, with his seven-year-old son Younes in the back, waiting for rush-hour traffic on Highway 102 to ease before taking a quick right and merging into the throng of vehicles.

The late-afternoon sun poured through the windows and Mohammad grabbed aviators swinging on the rearview mirror.

He pulled into the preschool’s tightly packed parking lot and tapped a button on the van’s ceiling, which slowly dropped a ramp to the pavement. Mohammad gripped the arms of the front seats and twisted his body to slide into the wheelchair in the back. It's a process that's been repeated every time he's run an errand, fetched a child or visited a friend.

He headed to the door of the preschool and gathered his smiling son in his arms.

Just as they were about to pull away, a teacher jogged out to the van and handed Mias a pink Mother’s Day card that will likely find a home on the family’s living room wall.

When Mohammad isn’t shuttling kids to school, he and Jawaher are learning English.

For now, Jawaher spends Saturdays teaching Arabic at the YMCA and planning community events, but she hopes to start teaching math again. Mohammad, who has reached Level 5 in English, says if he can get to Level 6 by September he plans to study architecture at Nova Scotia Community College.

He’s become known in Halifax for his annual Shokran Canada events, organized as a way to say thanks to his adoptive home. There's Syrian food, dancing and plays about the experience of starting again in a new country.

It’s a role he’s continued since his days as theatre director in Jordan, where he staged productions for fellow refugees to inject a little fun into hard lives. It was also, Mohammad says, a way to let the world know “we are refugee in the camp, but we have a life.”

This is the kind of resiliency that Dr. Meb Rashid, medical director with Crossroads Clinic at Toronto’s Women’s College Hospital, says he often sees among newcomers.

“I can give you dozens of stories of people who arrive and have gone through experiences where it would break me,” he says. “But they put their lives together, they dust themselves off, they’re eager to contribute, they’re the ones out on Canada Day waving the flag.”