March 24, 2019

Warning: This story contains disturbing content.

Ramiro Cristales felt a sharp pain as the machete sliced through his fingers, a cut that was meant for his neck but still drew a mess of blood. As he sprinted away screaming, he heard two gunshots follow. Both missed him.

Cristales remembers he was about 14, overworked, underfed and painfully thin — and all he wanted when he arrived home a little earlier than usual that night was something to eat.

The man Cristales says had attacked him that night in a drunken rage was forcing him to work at the family farm in rural Guatemala, insisting he put in 17-hour days — and not a minute less.

To Cristales’s dismay, he also insisted on the boy calling him Dad.

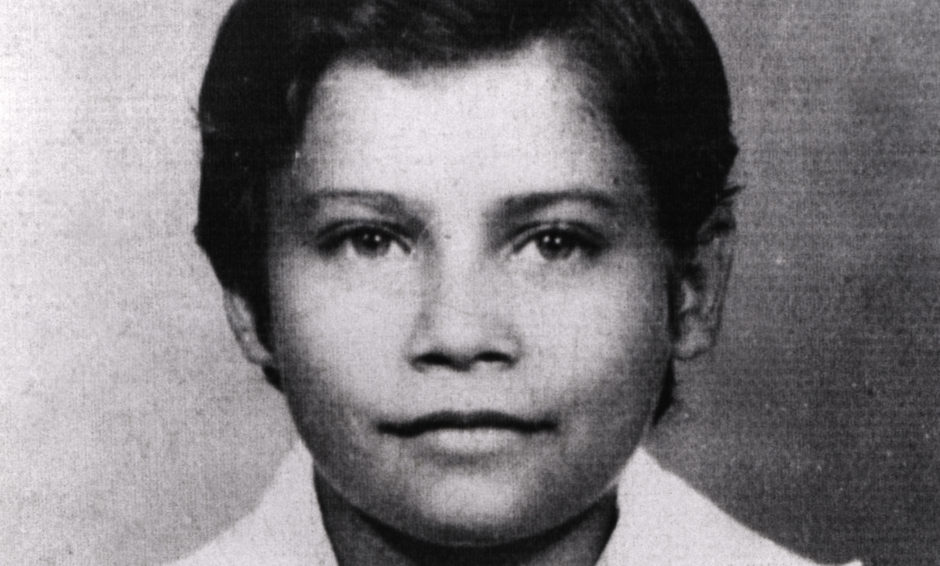

When Santos Lopez Alonzo adopted him, Ramiro Cristales was all of five years old, a newly orphaned boy with brilliant green eyes and a will to survive.

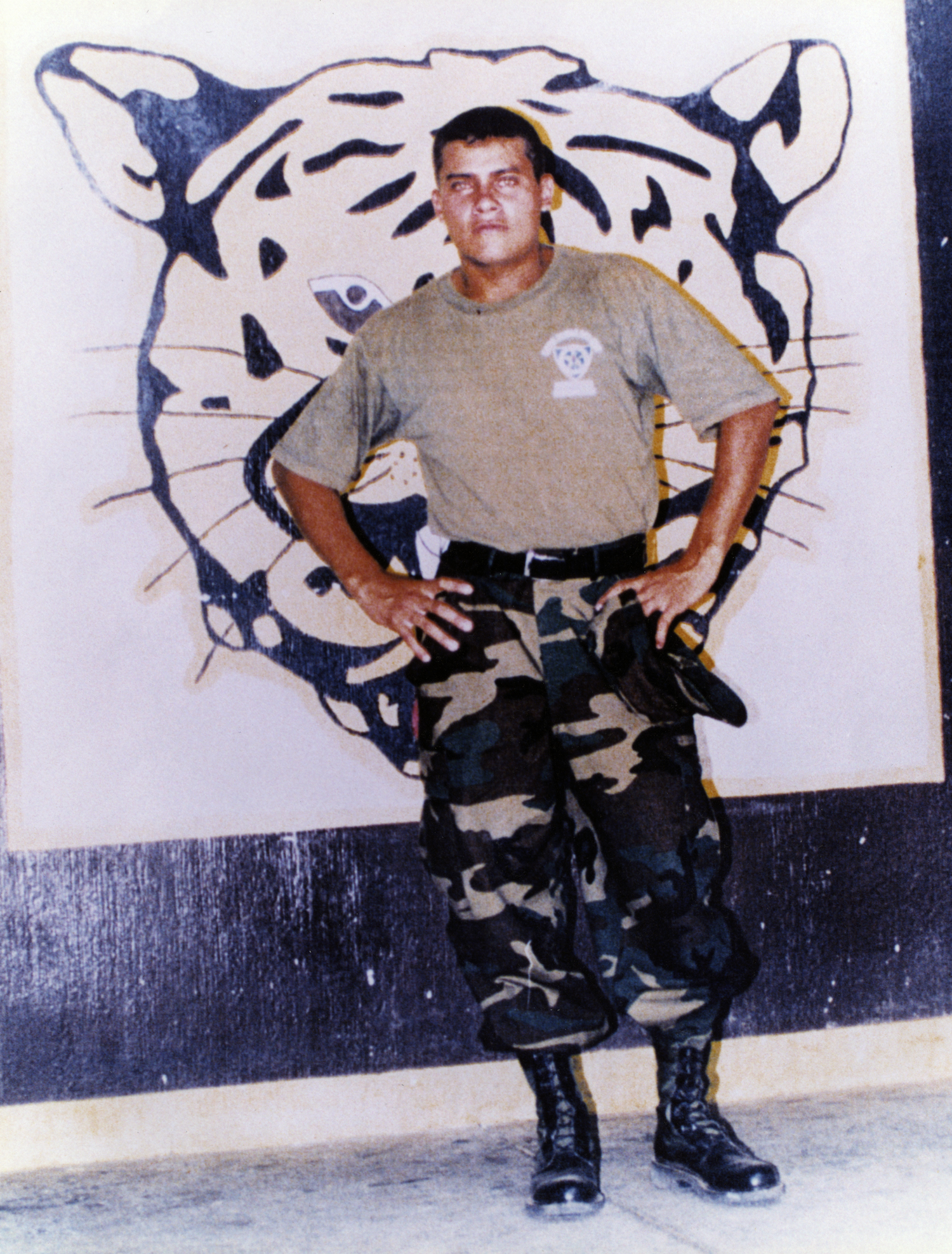

Violence underpinned their relationship, and it was in fact war that first joined their fates back in 1982, with Lopez, a soldier in the elite Kaibiles unit of the Guatemalan army and Cristales a boy who had just seen his family for the last time.

The events of that day launched Cristales on a dark odyssey that at times defies description: a long, meandering quest for justice that brought him to a secret life in Canada and back to Guatemala again — a lifelong pursuit that is now at risk of unravelling.

On that day, in 1982, Cristales also began living a harrowing and at times implausible chapter of his life. It included living with Lopez — not so much as father and son, he says, but as master and slave — endlessly clashing in their own drawn-out civil war.

During his teenage years in the early ’90s, Cristales was in constant fear of Lopez’s erratic, drink-fuelled violence and his ever-ready rifle — as were neighbours who came to his aid that night he says Lopez tried to kill him. So Cristales tried to steer clear of him and bided his time.

“I was just thinking to just hold, hold and [be] patient,” he told CBC’s The Fifth Estate.

But since that day they met, back in early December of 1982, Cristales was fighting another battle: one against the urge to kill the man he called Dad.

II.

Nothing about Ramiro Cristales now immediately gives away that he’s spent most of his life eluding threats.

He seems comfortable in his own skin: a soft-spoken Canadian of Guatemalan heritage who also happens to have an inconceivable story of survival.

Since 1999, he’s lived under the radar in Canada. And throughout that time, he has refused to celebrate Christmas.

December is agonizingly enmeshed with the memory of losing his family, a memory that includes witnessing the killing of his little sister.

That particular episode was just one enduring image from a shocking coda to what had been an uncomplicated existence for Cristales and his six siblings in the village of Dos Erres, a hopeful settlement of farms nestled within lush jungle in the northern Peten department of Guatemala.

Cristales’s family grew corn, beans and rice, and raised pigs, cows and chickens. He was destined for some schooling but more likely a future in farming. He wasn’t old enough to ride horses yet, so the pigs had to do.

He had a twin brother, Eldo, and other brothers with names like Victor and Hector. His parents were Victor and Petrona.

At the time, Dos Erres was a relative oasis in a Guatemala that was a cauldron of chaos. But 1982 was an exceptionally brutal year in the civil conflict that had raged since 1960 between U.S.-backed government forces and leftist guerillas, supported by the Indigenous Maya. It was Mayan people who took the brunt of the violence. The rebellion followed a CIA decision to help remove a democratically elected president.

Earlier that year, General Efrain Rios Montt had taken power in a coup, and the military regime was bent on crushing the guerrilla fighters. Massacres and bodies were piling up.

Late in the year, fighters believed to belong to the guerrillas ambushed a convoy of soldiers not far from Dos Erres, killing several soldiers and seizing 22 rifles.

A few weeks later, in the early hours of Dec. 7, the war arrived at Dos Erres and turned out all the lights.

Armed soldiers dressed in civilian clothes came to try to find the fighters involved in the ambushes near Dos Erres, and to try to find the weapons they seized. They believed that, at best, the village harboured guerilla sympathizers.

The following version of what happened next is gleaned from court documents, testimony from participating soldiers, government archives, interviews with investigators in Guatemala and Cristales’s own recollections.

“It still feels like it was yesterday because it's something you never forget,” Cristales, now 41, said in an interview with The Fifth Estate.

The gunmen roused everyone from bed and marched them to the centre of town. Cristales remembers his mother and father tied with rope and marched out.

His father said: “Everything will be OK,” recalled Cristales. But “it wasn't.”

It would be the last time he saw his father alive. Men were corralled in the school. Women and children were taken to the church.

What unfolded next was beyond the vilest imagination: the soldiers started by torturing the men and killing them, and then raping the women and killing them.

The worst of the violence unfolded by the village’s unfinished well.

Men, women and children, shot or bludgeoned to death, were dropped into the well. Some were thrown in still alive. At one point, at least one man threw in a grenade.

Dozens of others were killed elsewhere around the village. In the church where women and children were held, Cristales and his mother were within earshot as the carnage unfolded. His face and voice take on the character of a child as he recounts the traumatizing ordeal he lived that day. “The moment when they took my mom was the hardest part for me,” he said in an emotional interview.

They were like animals.'

He remembers clearly the face of the man taking his mother away — long, with a square jaw and narrow, wide-set eyes, high cheekbones and a mop of short, straight dark hair. It is a face he would see again.

In desperation, Cristales and his siblings tugged at their mother’s leg as the men dragged her out of the church, to no avail.

“They were like animals,” said Cristales.

He ran to the back of the church to peek through the wooden slats to see what was happening to his mother. At that point, he saw one of the men grab his little sister by the feet and swing her against a tree. He heard his mother pleading with them: “Please don’t kill my kids.”

Then came the moment when Cristales realized his mother was gone, too. “I was hearing my mom screaming for help, and then I hear no more.

“I was crying and crying.”

Exhausted, Cristales fell asleep inside the church.

Hours later, when the killing was nearly over, he remembers thinking he was certain he would be next.

Instead, the soldiers took him out and asked whether he recognized any of the bodies strewn around the village.

“I don’t know this person,” Cristales recalls saying when the men pointed to one body.

“The person hanging from the tree was my dad.”

It was a demonstration of Cristales’s survival instinct kicking in, one that he would come to rely on to carry on for years to come.

A handful of kids had survived. One boy escaped, and at least two other girls, who were raped, were later killed, too. When it was all over, there were just two boys left: Ramiro, 5, and Oscar, only 3.

Both had green eyes and light skin but were unrelated. The men intended to take them alive, as a trophy or an act of mercy — it isn’t clear.

The killing spree over, the men marched them into the jungle, and together they walked for days.

Bizarrely, one of the men took a shine to Cristales and started feeding him. He remembered the long face: he was the man who took his mother away.

A few weeks later, that man would be taking him to his home.

III.

In the immediate aftermath and for many years afterwards, the chatter in Guatemala about what happened in Dos Erres was whispered and nervous. A real investigation would take years to materialize.

To the rest of the world, more than 200 residents of the village, including Cristales, simply disappeared.

The “official” version, related just days after the massacre by military officials posted nearby, was that rebel guerrilla forces had attacked the village and marched its inhabitants into the jungle and possibly west to the Mexican border, less than 50 kilometres away.

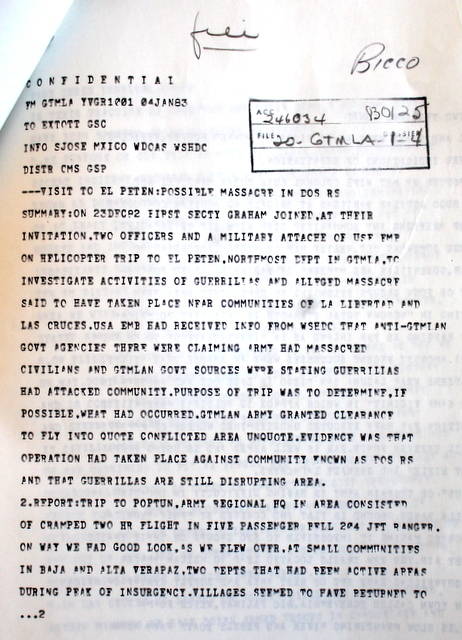

That version was reported in one of the earliest inquiries into the massacre. It was undertaken by one Canadian diplomat, two American diplomats and a U.S. military attaché who flew over what had been Dos Erres in a helicopter slightly more than two weeks after the attack.

In archived government documents obtained by the CBC, a report to the federal External Affairs Department marked as “confidential” by the Canadian diplomat, described their journey. It noted there were two versions of the events that led to the abandonment of Dos Erres. One blamed guerrilla fighters. The other blamed the military.

In the first version, Dos Erres was a place that harboured “guerrilla sympathizers and possible collaborators.”

The diplomats flew over the area, noting “seven to eight houses had been put to torch” and that its inhabitants were gone. The report goes on to say it was “odd” there was no information about their fate two weeks after they disappeared.

The report notes that officials and people in the nearby village “were slightly evasive,” though also co-operative.

U.S. documents from the same trip obtained by ProPublica were more definitive, saying “the party most likely responsible for this incident is the Guatemalan army.”

The Canadian diplomat concluded that questions remained. “Were inhabitants led into woods [by guerrilla forces] as in official version, or were they executed by army, perhaps in revenge for ambushes, and burned in mass grave?”

The latter version would eventually prove closer to the truth. That truth was arrived at by the courts with the help of witnesses. But the initial digging into all this was done by activist Aura Elena Farfan, who was the first to actively investigate the massacre a dozen years after it happened.

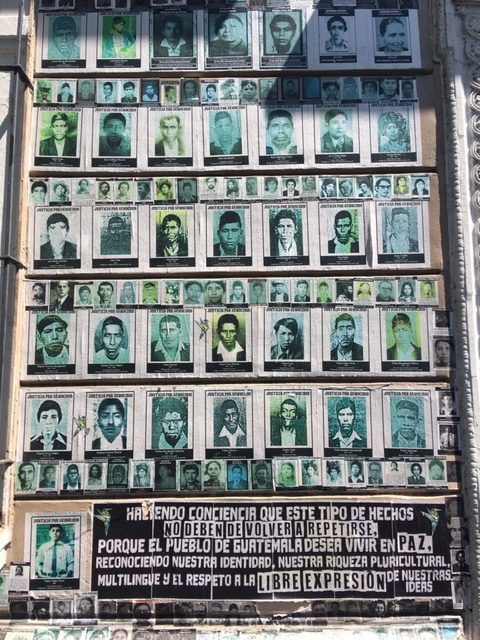

Now 79, Farfan is still the head of FAMDEGUA, the association of relatives of disappeared prisoners in Guatemala, which helps families find out what happened to some of the nearly 250,000 people killed or missing in the war.

Farfan’s own brother was disappeared in the conflict. His picture hangs among rows of faces that line the lime-green walls at the FAMDEGUA headquarters in the central zone of Guatemala City.

Farfan decided to investigate after repeatedly hearing the stories about the well that became a mass grave in Dos Erres.

In 1994, she dared to do what few would. She visited Dos Erres, which had until then been overgrown and abandoned to its grim past.

What they discovered, over several visits, was horrifying: the remains of at least 162 bodies, 67 of them children. The exhumation unearthed mountains of bones damaged by blows, fractured by the fall and browned by time.

They found heaps of clothing tattered by the years. Those would later help families identify some of the remains.

The pictures of their finds are chilling. Seeing them in person was traumatizing.

“I felt a lot of pain,” Farfan said in an interview at FAMDEGUA. “What I did was to walk through the forest to scream and cry because of the pain in my heart because of what I was seeing.”

Farfan wasn’t content to let the truth remain buried. She put out a call for information, and two men who had been with the unit in Dos Erres came forward.

It is how she learned that during the course of a massacre that claimed the lives of dozens of children, two boys had been abducted — and are still alive.

IV.

It was only when five-year-old Cristales landed by helicopter at a sprawling military base after leaving Dos Erres that he realized the men who had wiped out his village and his family were soldiers in the army.

Even at that age, he said, he was alarmed by that discovery, sensing he was not safe among the uniformed men.

Cristales said he and Oscar, the other boy who was spared, then endured about two months on the base. During that time, Cristales said, he was questioned about the presence of guns in the village.

He recalls he and Oscar were often dressed up in olive greens and treated like “pet soldiers.”

Soon, the soldier with the long face he had seen back at the village church was taking him home.

That soldier changed his name and gave him a new birthdate: June 30 — oddly, the same date as Guatemala’s Army Day.

No one outside that base knew. As far as his extended family was concerned, Cristales had met the same fate as his family.

Many years later, Aura Elena Farfan would discover otherwise. Unlike the bones she had unearthed in 1994, she knew Cristales was alive somewhere.

With the help of Sara Romero, a young prosecutor who was assigned to the Dos Erres case, Farfan located the soldier who had taken Cristales, and in 1999, the two of them decided to knock on his door.

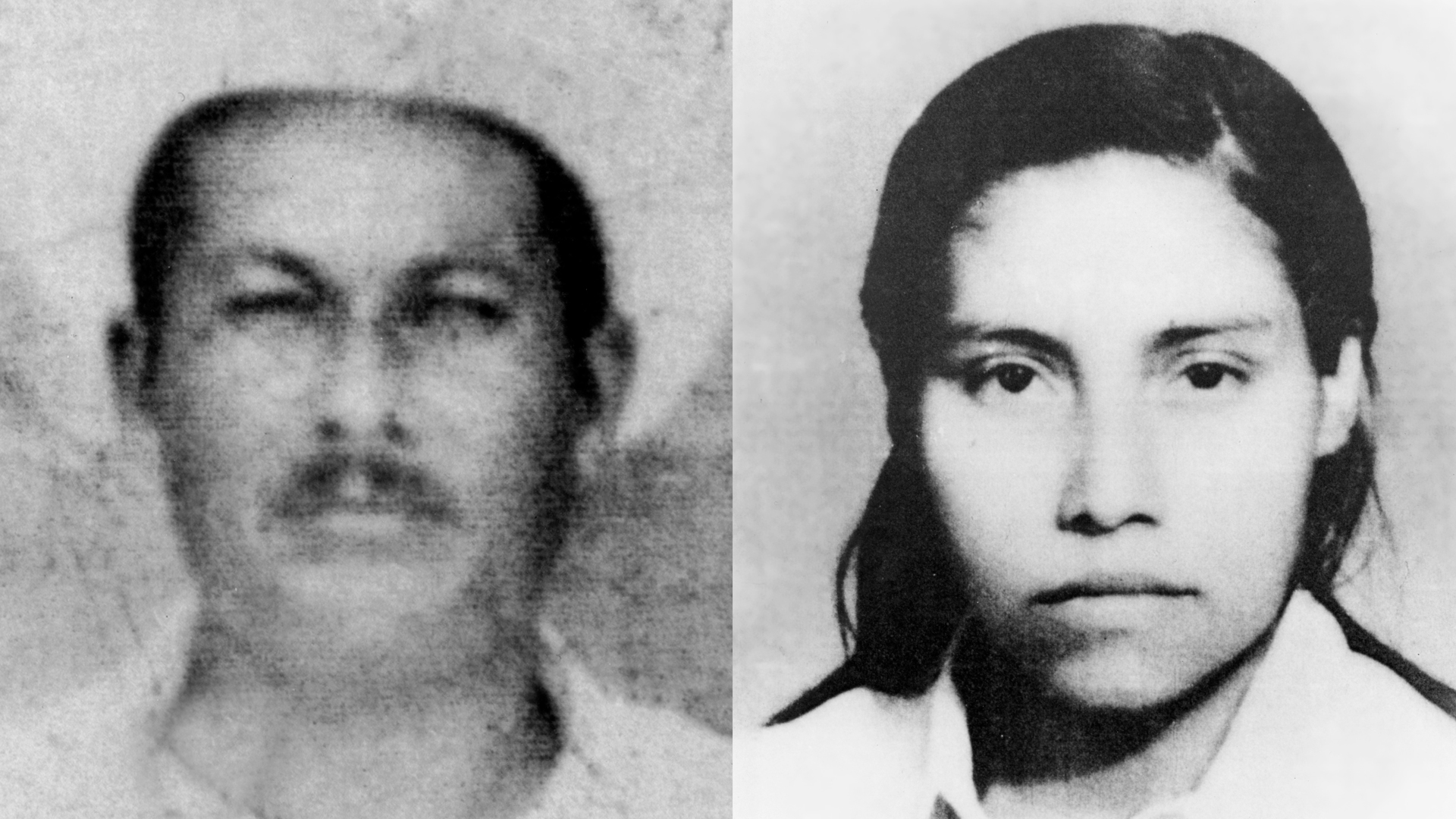

His name was Santos Lopez Alonzo.

“I felt disgusted,” said Farfan. I felt very angry to go to that man’s place knowing what he had done, and he kept the child.”

Romero told him they already knew everything about what happened at Dos Erres.

Unexpectedly, said Romero, Lopez confessed to taking part in the massacre – but he would only talk on condition that none of it was written down.

“He just told us everything as if it was weighing on him,” said Romero.

Lopez, she said, addressed the killing head on. “He told me: ‘It was like we all had the devil inside. It was a feeling of euphoria, for seeing so much blood.’ ”

In more than 15 years of living together, Cristales never confronted Lopez over what happened at Dos Erres.

By the time the two women visited, Cristales had grown into a young adult, the eldest boy in a family that wasn’t his own, and still living with the man who had taken his mother away nearly two decades earlier — a man with a rifle and a mean streak that seemed reserved especially for Cristales.

Crtislates became accustomed to the violence, along with the hard work.

When Cristales dared to come home early to eat that night back when he was 14, he had been working in Lopez’s newly acquired pineapple field.

Cristales said that before Lopez attacked him with the machete that he’d been using for work, he first beat him on the head with the butt of his rifle. Then he grabbed the machete Cristales was wearing at his waist, and started to cut what he thought was his neck. Cristales had put him his hand up to protect it — he still has scars that he says proves it.

“Please don’t kill me, please don’t kill me,” he recalled telling Lopez.

While he was constantly at war with his abductor, Cristales was simply trying to survive and bide his time. He often cried himself to sleep.

“I never felt safe,” he said.

“He always say … 'If you're planning to run away, I will find you no matter what. It can be six metres under the ground, I will find you and I will kill you.’

Cristales said the history, and the repeated abuse, made him want to kill Lopez, an urge he overcame because “I don’t want to be [like] him … a killer.”

“I just pretend to live my life like normal, but inside of me was like a volcano, sleeping.”

Inside that volcano was still a grieving child desperate to find his parents, even if they were dead. That child also desperately wanted someone to find him.

Romero and Farfan were determined to rescue Cristales and bring the killers to justice. But to do that, they had to get past the man who had abducted the young boy.

“I asked him, where is Ramiro?” Romero said in an interview at the public prosecutor’s office in central Guatemala City.

To her shock, Lopez informed her Cristales had joined the army, the very institution behind the killings in Dos Erres. But Lopez wouldn’t tell her where exactly he was.

Determined to find out, Romero inquired directly with the military. But by asking, she feared she had drawn attention to Cristales — both as survivor and living evidence of a massacre in which soldiers had been involved.

That may have put Cristales in grave danger, so the two women were desperate to find him quickly.

Lopez eventually changed his mind and took 21-year-old Cristales out of the army and personally delivered him to Romero. It was 1999, 17 years after he abducted him and took him home.

But like his decision to abduct him in the first place, by handing him over to Romero, Lopez also sealed his own fate.

Over several days, Cristales began reclaiming his identity and the sordid story buried deep within his childhood memory.

To his surprise and joy, he was also introduced to family he didn’t know he had: grandparents, uncles, cousins.

But he wasn’t safe in Guatemala. Farfan and Romero lobbied diplomats from Australia, Spain, and the U.S. to take him out of the country, but Canada was the first to agree to give him asylum. Within days of being found, Cristales was on a plane to less familiar terrain.

He would live in secret in an undisclosed Canadian city until he was needed to testify back in Guatemala.

For the first time since his childhood was wrenched away from him, Cristales felt hope.

V.

Cristales likes to show off pictures of himself at work in Canada as if they are holiday snaps. In one of them, he’s wearing several protective layers of clothing as he squints into the winter sun. The photos are from his last construction gig — working outdoors in sub-zero temperatures.

It is 2019, exactly 20 years and many degrees away from the breezy, warm days of his life in Guatemala. Cristales is married now with three children and has become a Canadian citizen. And he has found a comparatively comfortable place for himself among fellow Canadians.

For his own safety, he still prefers not to reveal his exact whereabouts.

Life in Canada wasn’t easy at the start. Even with the danger, he frantically wanted to go home. His social worker told him he couldn’t. He was a refugee now.

He said he fell into depression and was even suicidal.

Cristales put those days behind him when he began to exercise his new role. He testified at several trials related to Dos Erres — both in the U.S. and Guatemala — telling and retelling his story, before returning home to his quiet life in Canada.

“I'm the voice of the people” who died, he said. “I'm the light in the darkness: [which is] what the army did to our village and the people. And I will do whatever I can to get justice.”

Eventually, one of those things was to testify against Santos Lopez.

Before that happened, Lopez had moved to the United States. Cristales had stayed loosely in touch out of some sense of gratitude for sparing his life — until they had a dispute, and Cristales confronted him for the first time on the telephone.

“I told him: ‘You don’t remember? You killed my own family?’ And he went silent.

“The next time I see you, you will be in jail,” Cristales recalled telling him.

Cristales had learned where Lopez was living and reported him to his lawyer, who in turn informed Interpol. As a result, Lopez was extradited to Guatemala in 2016 to face charges of war crimes — and for abducting Cristales.

"He who owes nothing fears nothing. If I had done something, if I had killed, I would be afraid, but I feel clean," he told The Associated Press in 2016 prior to being extradited.

Lopez and Cristales eventually found themselves inside the same Guatemala City courtroom: Cristales, once the victim and now on the offensive, and the old combatant as defendant.

Cristales said he could not look at him or use his name. He would only call him “that man.”

Lopez had always contended he was a baker and that he was only following orders when he guarded women and men in Dos Erres who were later taken to be killed. He insisted he did not participate in the killing.

The prosecutor painted him as a “material author” of the massacre, according to a report on the trial by International Justice Monitor.

A psychologist, said the report, testified that Cristales “suffers serious psychological harm” and “terror and extreme sadness” because of his early experiences, and that as a result of the “semi-servitude” in the home of Lopez, “he lives in a perpetual state of fear, anger, sadness and defencelessness.”

Last November, Lopez was convicted of being “responsible as author” in the massacre, and sentenced to 5,160 years in prison: 30 years for crimes against humanity, and then a further 30 years for each of the lives of 171 people who were murdered in Dos Erres.

The court “acknowledged” the abuse Cristales endured, according to that International Justice Monitor report, but dismissed related charges because they were not crimes against humanity.

Still it was an important victory for Cristales.

“We get justice slow, but we get it,” he said. It was both a happy and sad occasion, “happy because we’re getting justice, and sadness because I’m not free.”

Cristales believes the risk of retaliation from military loyalists remains. He said he will always have to remain low-key to protect himself and his family, even more so, possibly, as an effort gathers pace in Guatemala that would see the likes of Santos Lopez walk free.

Reached by The Fifth Estate at a Guatemala City prison, Lopez declined to be interviewed and said he wished Cristales well in his life.

VI.

Beyond Lopez, five other military officials have been tried and convicted relating to the massacre at Dos Erres. They have so far been sentenced to more than 6,000 years in prison.

Others who were involved are serving time in the U.S. on immigration charges, one of whom was a Canadian extradited from Alberta to face those charges. Six other fugitives are at large.

As the convictions have mounted, a backlash has brewed among some in Guatemala who believe the military is being unfairly targeted as the country contends with its bloody history.

According to an independent UN fact-finding commission, the military and paramilitary groups were responsible for the vast majority of civilian killings, which number more than 200,000.

Initially, the Guatemalan justice system was slow to begin trying those responsible for the conflict’s worst crimes. A decade ago, that changed. And in 2013, Guatemala became the first country to convict a head of state of genocide.

That was Efrain Rios Montt, who was the head of the military regime when the massacre at Dos Erres occurred.

Montt appealed and Guatemala’s highest court overturned the ruling against him. He died at 91 years of age last year, before a new genocide trial could be concluded. But it still marked a turning point in a country where for many, exacting justice from the authorities had been elusive.

Meanwhile, there are many other cases in various stages of preparedness to go to trial.

Congressman Fernando Linares Beltranena is outspoken and unapologetic about his proposal to put a stop to it all and get men like Santos Lopez out of jail.

Linares is behind legislation that has wound its way through Guatemala’s Congress this year that, if passed, would give amnesty to all, mostly military perpetrators convicted of serious war crimes in Guatemala’s civil conflict.

A national reconciliation law passed in 1996 gave amnesty to all combatants in the civil war, but it specifically excluded those who were accused of the gravest crimes such as genocide, torture and forced disappearances.

Linares argues the amnesty should be extended to everyone accused of a crime during the war. That would include all those implicated in the Dos Erres killings.

“It’s a way to bring about peace,” he told the The Fifth Estate. He insists that victims and courts have pursued convictions out of vengeance — instead of a search for justice.

He added the 1996 amnesty was agreed to stop the fighting, and to his mind, “impunity is better than war.”

What would he say to people like Cristales who are desperate for justice? “You ask them to forgive,” he said.

If passed, the legislation would free, within 24 hours, about 30 ex-military and at least one guerrilla fighter convicted of war crimes.

The UN’s human rights commissioner described it as a “drastic step backwards for the rule of law and victims rights,” and could lead to retaliations against those involved in the search for justice.

Earlier this month, the bill was up for third reading in Guatemala’s Congress. Several countries, including Canada, called for the bill to be withdrawn.

“Canada is deeply concerned” by the proposed law, Global Affairs Canada said in a tweet. “Changes to the laws could undermine the #ruleoflaw and allow for #impunity.”

Before the vote could be held, several legislators walked out in protest, and Congress failed to reach quorum for a vote.

But the bill may yet return for a third reading.

Victims groups and rights organizations have protested what they call an attempt to erase history.

“It's like a slap in the face,” said Cristales. Those who murdered and raped can still be free, he added. “That’s not fair,” he said. “What about my rights?”

It is a question often posed in Guatemala.

In countless posters dotting the walls, faces of the disappeared still haunt Guatemala City, still demanding to be found.

Hundred of unidentified remains sit in boxes at a Guatemala City compound that is the headquarters for the Guatemalan Forensic Anthropology Foundation (FAFG), an organization dedicated to identifying the war dead.

There are so many that overflow of boxes sit in a hallway. Every box contains a set of remains without a name.

FAFG executive director Fredy Peccerelli said his work is mostly funded from abroad, and at home, it has earned him threats.

“There are people that are afraid of us. There are people that now understand that what we do could put them behind bars.

“Unfortunately Guatemala still has not accepted what happened, so some of the people, some of those perpetrators, still have power. ”

But Peccerelli said it’s living witnesses like Cristales who would bear the brunt if Congress passes the proposed law and throws all the convictions out.

“It's the witnesses themselves that are one vote away from all of a sudden going from heroes to traitors. Right? Against their own military, against their own country.

“If they pass that law … people like Ramiro would not be able to set foot in Guatemala probably ever again.”

VII.

For years, Cristales occasionally hoped beyond all hope that somehow some of his family survived the horrors of Dos Erres, just as he did.

These days, he simply wishes there was a place he could go — a cemetery, a gravestone, anything — where he could “speak” to his family.

Many relatives of Dos Erres victims buried the exhumed remains of their family on July 30, 1995. Not Cristales — FAFG has had no luck finding a match.

Cristales said he stays connected with them through his prayers.

“They are with me, everywhere — wherever I go, they are with me,’’ he said through tears.

Starting a new family has taken the edge out of missing his old one. But it has been difficult for him to explain to his children why they don’t have grandparents on his side.

“I try to be strong when they ask me, but they broke my heart,” he said.

Cristales is a survivor of so much evil that was beyond his control. But he’s also managed to stave off the urge to return in kind.

“I cannot forgive him. But I cannot live with anger. Because if not, I will destroy myself, and that's not a life.”

With files from Reuters