June 30, 2021

WARNING: This story contains distressing details.

Indigenous children suffered abuse, racism and loss of culture at Indian day schools that operated across New Brunswick in the last century and at the Shubenacadie Indian Residential School in Nova Scotia.

The discovery of what are believed to be hundreds of unmarked burial sites of children's remains at former residential schools in Kamloops, B.C., and the Cowessess First Nation in Saskatchewan has reopened old wounds for many survivors in New Brunswick.

Here are the stories of five of them: Edward Peterpaul, Vaughn Nicholas, Francis Simon, Kelley Peters and David Perley.

Edward Peterpaul: Keeping a secret

Edward Peterpaul was cleaning the outhouses behind Big Cove Federal Indian Day School when he was sexually assaulted by the principal of the Catholic Church-run school.

“When that day happened, everything just shut down,” said Peterpaul, now 74 and living in Elsipogtog First Nation, about 90 kilometres north of Moncton.

In Grade 7, he was about to use the washroom when the principal came up behind him and locked them both inside.

“He just didn’t say anything or nothing,” said Peterpaul. “He just grabbed the door and inside the door, there’s a big wooden latch that … will lock itself.

“Boy, I’ll tell you, my head exploded. The pain in my body was so great it was unbelievable. I couldn't help myself or anything. I couldn’t do anything. All I felt was pain.”

Peterpaul immediately went home to tell his grandmother, but she didn’t believe him.

'I thought I was going to die.'

“She told me, ‘People don’t do that. People don’t do that to kids.’”

Peterpaul swore through his tears and headed upstairs, where he cut the sleeves off old shirts to stop the bleeding. He said he did that for several days.

“Oh my god, I thought I was going to die.”

Peterpaul couldn’t walk or sit, and forced himself to lie on his stomach.

During the assault, a nail cut into his stomach. A week later, he started throwing up and that part of his stomach turned purple.

“When he pushed me, the nail went through my stomach and I didn’t even feel that.”

Peterpaul had moved to Elsipogtog from Maine when he was in Grade 5, after his father died and his mother remarried.

“My mother dumped us in the reserve,” he said.

“I didn’t have anybody but my grandparents, and they were too old to understand what was going on. And they didn’t care because they had their moonshine going for them.”

After the assault, it took Peterpaul years to return to school and get his GED and counselling degree.

‘Just die’

In the mornings, he’d get ready for school but then hide in the woods or by the river for the day.

“I was ashamed to go to school,” he said. “I didn’t want anybody to know what happened.”

He also tried to kill himself by drowning and by taking stolen pills.

“I was totally lost. There was nothing in my mind other than just die, just die.”

He was sent to the Restigouche Hospital Centre in Campbellton, N.B., and worked with a psychiatrist for a year.

“I told him everything,” he said. “There were a lot of tears. A lot of pain. It was like a flashback in your mind.”

When Peterpaul was in his 50s, some friends opened up about the teachers slapping them with rulers and about the sexual assaults by the school principal.

“The principal only targeted people that were vulnerable; that their parents were alcoholics, they’re not paying attention to their kids,” he said.

Peterpaul never shared his story with his friends.

“I didn’t want anybody to know what happened. It was too painful.”

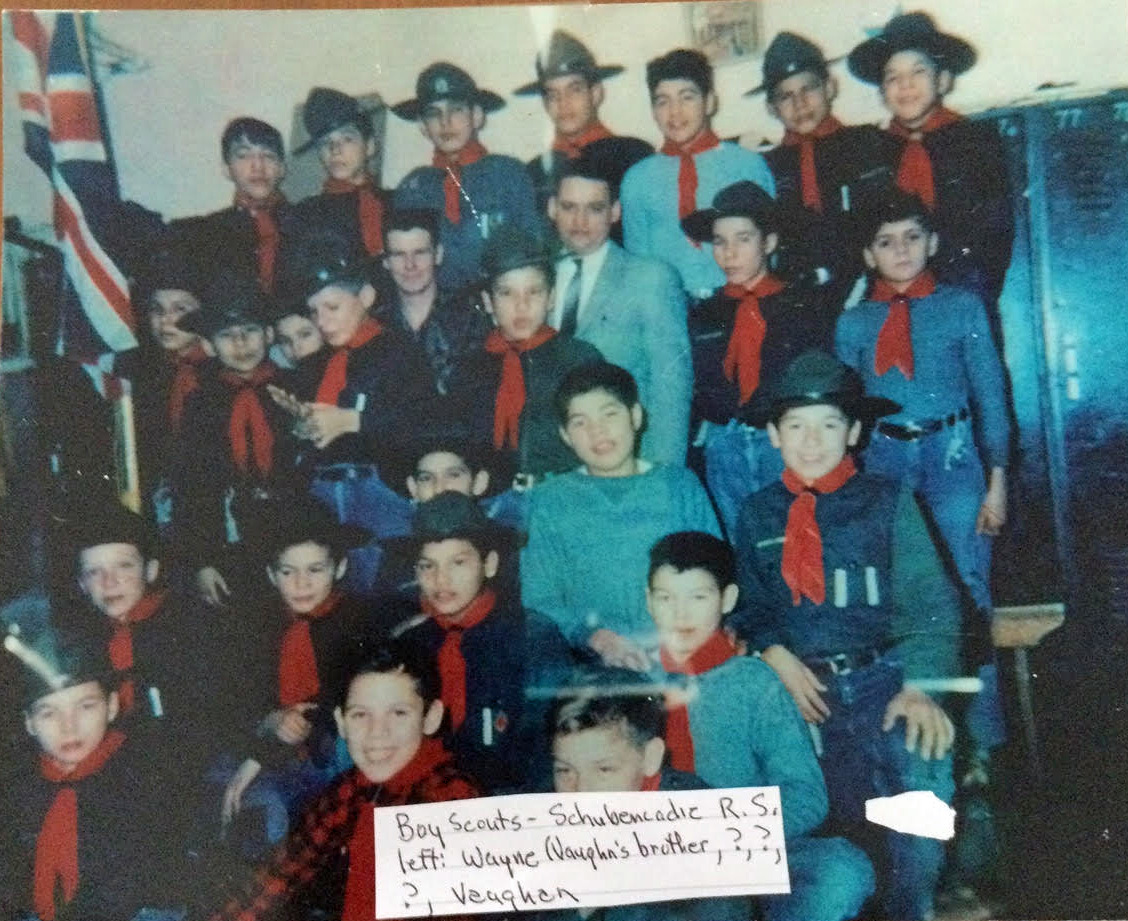

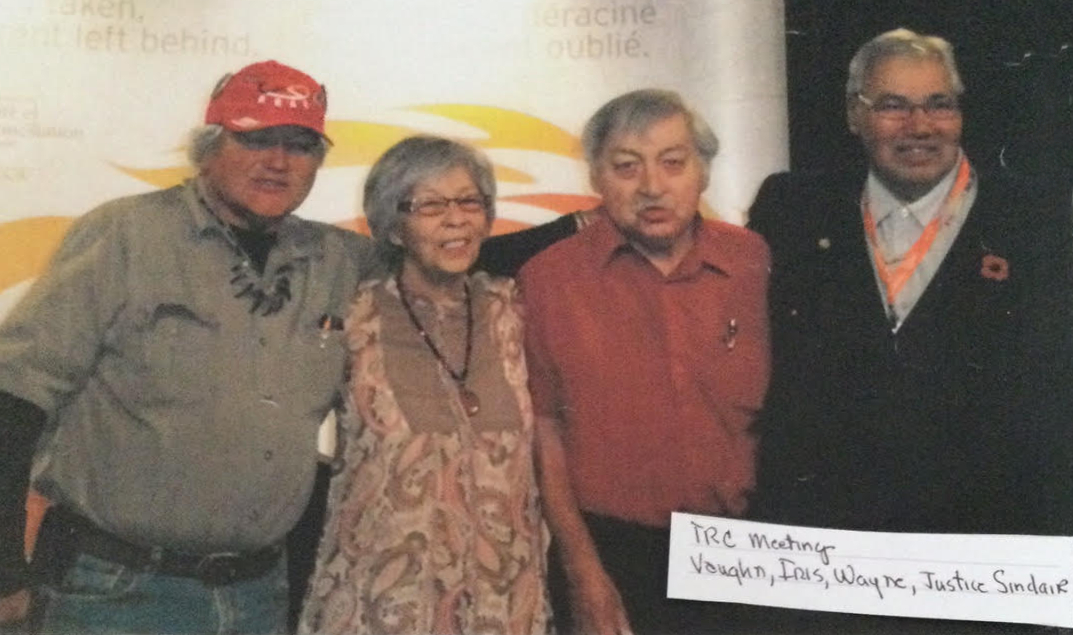

Vaughn Nicholas: Number 41

Vaughn Nicholas celebrated Christmas Day for 30 minutes in a room with his brother and sister.

There were no presents. Just enough time for “Hi” and a brief catch-up.

“After that, we don’t interact again as a family,” Nicholas said from his house in Tobique First Nation, in western New Brunswick. “Not until Easter for another half-hour."

He and his older brother, Wayne, and younger sister, Iris, were taken to Shubenacadie Indian Residential School in the fall of 1955.

They were among thousands of Indigenous children across the Maritimes who were forced to attend the Nova Scotia school, which operated from 1929 to 1967.

“We didn’t know where we were going,” said Nicholas, who was starting Grade 2. “We thought we were going on a trip, the three of us.”

They left their home in Tobique First Nation early in the morning by car and arrived at the school late at night.

Before the trio made it inside the building, Nicholas’s little sister started to cry.

“She didn’t want to go in,” said Nicholas. He had to drag her.

He spent two years at the day school.

Then the siblings were sent to Shubenacadie by an Indian agent, someone who exerted significant control over a First Nation reserve as a representative of the federal government.

The children’s mother was sick with tuberculosis. Their father was working and struggled with alcohol abuse. Their grandmother couldn’t take care of them and they didn’t have a lot of money.

“Before that, I just remember a happy life at home,” said the 74-year-old. “Lots of laughter.”

A horror film come to life

When their father said goodbye, the three kids begged him not to go. Nicholas got permission to see his sister in her dormitory and tried to comfort her.

“She cried herself to sleep.”

That first night at Shubenacadie, Nicholas said, one of the nuns walked toward the children down a long hallway.

“It sounded so eerie,” he said. “It sounded like a horror movie.”

The next day, he remembers taking a shower and being scrubbed with some kind of product all over his body.

“It literally burned my body. I was crying while they were doing that.”

Afterward, he got a haircut, also known as a “Shubie cut.”

“It’s almost like they put a bowl on your head and then shaved right around it,” he said. “It was a funny-looking haircut.”

The number 41 was stitched onto the shoes, pants and underwear he was given and was also on his locker.

“Everybody had a number at the school.”

Cows are sacred

Then the beatings started.

Some of the nuns clipped straps onto their robes. One carried a metal ladle from the kitchen.

“They seemed to like spanking the young kids,” he said. “It was a normal thing, a daily thing.”

Nicholas was strapped for not cleaning himself properly. He was hit for trying to say hello to his sister when he spotted her at breakfast.

He was slapped twice for coming into the classroom and saying, “Holy cow.”

“It’s just like taking the lord’s name in vain,” he said.

“That’s all I knew about cows. I didn’t know they were sacred.”

He was told cows are considered sacred in some parts of the world. Nicholas found this confusing because his grandparents had a barn with cows and chickens that were slaughtered every fall.

'The howling, the screaming, the crying that came out of those two boys, it scared the living daylights out of me.'

One night after the boys in his dormitory said their prayers, a nun turned the lights off and closed the door. They didn’t realize she’d stayed inside the room.

A few minutes later, two of them started speaking Mi’kmaw.

The lights came on and the nun ordered the two boys to bend over with just their nightgowns on.

“She started hitting them — bang, bang,” Nicholas said. “It was no light spanking. I could hear the smacks.

“Bang, bang. Ten times each. The howling, the screaming, the crying that came out of those two boys, it scared the living daylights out of me.”

Freedom day

By June, Nicholas said, many kids were happy because they could return home.

“Freedom day is coming.”

But Nicholas and his siblings weren’t the same kids when they left. They couldn’t remember how to speak Maliseet, the language more often called Wolastoqey today, and struggled to answer when their father asked questions during the ride home.

“Every time he asked a question, ‘Yes father, no father,’” Nicholas said.

During summer, he tried to block out what happened at school. “What did we do wrong to be treated like this? I never got treated like that at home.”

Shubenacadie ended in Grade 8, and Nicholas went to high school back in New Brunswick, where he started to drink heavily and struggled in school.

A life lost

After he graduated, he got married and had a family of his own.

But the beatings didn’t stop.

He would hit his daughter and two sons, especially if he had been drinking. He hit his wife Bernadette when she was pregnant.

“I hit them, and I hit them hard, just like the nuns hit me,” he said through tears.

In 1975, he vowed he would never drink or hit his wife again, but he was still strict with his three children, sometimes using a ruler on them.

Fifteen years later, his son Corey died by suicide at 17.

“It was probably the way I treated him over the years.”

Memories of Corey’s death are a constant reminder of what happened to Nicholas at Shubenacadie and the life he, too, lost.

“They were doing what they got hired [to do] by the government of Canada, the Catholic Church — to take the Indian out of us,” he said.

“I think they’ve done a good job with most of us."

Francis Simon: The great escape

Francis Simon had been at Shubenacadie Indian Residential School for a few months, when he and his younger brother, Bryant, planned their escape.

“In the morning, I would look out the window and wish I could go home,” said Simon, who slept in a dormitory which had about 30 beds.

“We used to hear the sound of the train and we knew that that was the way home.”

Then eight years old, Simon got the idea for an escape watching The Great Escape on the projector in the downstairs rec room of the school.

Going home

“We were going to take the train tracks and go … as far as we could,” Simon, now 66, said from his home in Elsipogtog First Nation.

But Simon, his brother and four other children only made it to the Shubenacadie Wildlife Park, where they were picked up by RCMP.

Crammed into the backseat of a police cruiser, they begged not to be sent back.

“We were telling him, we were going to be in big trouble for running away. He said, ‘They’re not going to hurt you.’”

When they were returned to the school, Simon and the others were bent over a chair to be whipped with a belt strap by two supervisors and a brother with the Roman Catholic Church, which ran the school.

Simon still remembers the 12 lashes among them.

“There was silence,” Simon recalled. “Hardly any of us would cry. I guess, of course, it was a sign of weakness.”

Simon was also whipped on his back.

“It hurt a lot. Worse than anything I’ve ever felt. I was gasping.”

'I was scared'

After the beating, he noticed blood when he urinated.

“I was scared. I didn’t know what was going to go on,” he said. “I knew I’d be in trouble and I didn’t want anyone to find out.”

Simon got sicker as an infection emerged and he was eventually sent to a doctor in Truro, N.S., about 35 kilometres north of Shubenacadie. He was told he had a bruised kidney.

The doctor was angry with the brother who beat him, and he threatened to call police if another child was brought in with similar injuries, Simon said.

The brother tried to justify the beating.

“He told them, ‘We have to because we have no fences, and that’s the only way to keep them in here … strict discipline.’”

Why were they sent there?

Simon had spent part of his childhood in Germany and then Petawawa, Ont., places his father was stationed as a member of the military.

After the family moved back to New Brunswick, his parents divorced, and Simon’s mother had to support all eight of her children. She often picked blueberries to sell or to feed her children for breakfast.

That’s when the federal government stepped in. An Indian agent took Simon and his three siblings to Shubenacadie, almost 300 kilometres away.

“We heard stories about the residential school. Anyone who was bad went to the residential school. … We couldn’t understand why we were there.”

Simon was at Shubenacadie from 1963 to 1967, taking science, math, history and other subjects and going to church every day.

The kids were forced to send only positive letters home.

“If my mother knew what they were doing to us, she never would have let that happen.”

‘He was my best friend’

Eventually, Simon’s brother Bryant got sick. One Sunday in church, Simon remembers his little brother falling over beside him and throwing up.

He was sent to the hospital in Halifax, where he was diagnosed with liver cancer. He died a few months later at the age of nine.

“I couldn’t understand why he was gone. We were just kids, nothing more. We had our life to live and he never got a chance to.”

After Bryant died, another younger sibling took his place at the school.

Simon left Shubenacadie at the age of 12, when his mom realized what was happening at the school.

“I do harbour the bad will against the government for sending me there,” he said. “And the Roman Catholic Church for being the boxing gloves.”

He was angry after the discovery of what are believed to be the unmarked burial sites of children's remains adjacent to a former residential school in Kamloops, B.C.

“They were just kids. They came from homes. Their mothers loved them. Their fathers loved them. And they loved their parents,” he said. “I could imagine all they wanted to do was just go home.”

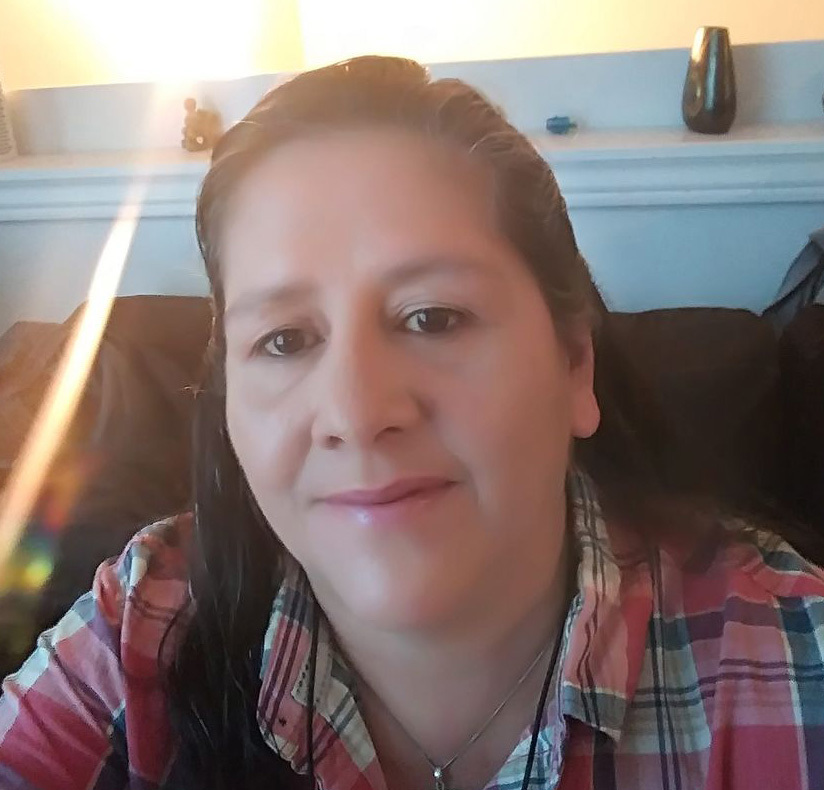

Kelley Peters: Fighting the bullies

Before the bell rang at Big Cove Federal Indian Day School, Kelley Peters would hide in the woods so bullies wouldn’t attack her.

But the attackers would corner her after school.

“They would touch you in places where you shouldn’t be touched,” the 55-year-old Peters said from Elsipogtog First Nation.

There were four boys — all older than she was. Sometimes they’d hit her and pull her hair.

“These guys just got a thrill out of it.”

Peters was at the school in the mid-1970s, from Grade 3 to middle school.

Sometimes she would lie and say she didn’t finish her homework, so she’d have to write 50 lines after school that said, “I will do my homework on time,” and “I will not be tardy.”

That way, the bullies wouldn’t harass her.

“That’s how I knew the word tardy.”

Getting ready in the mornings, she would layer herself in sweaters and tie an additional sweatshirt around her waist so they wouldn’t touch her.

“They would just grab me right down there, and on your ass and your boobs,” she said. “If you moved one way, somebody’s already grabbing you and you’re protecting that part.”

For years, she’s tried to block out what happened to her.

She thought the assaults happened about twice a week, but family members recalled it was almost daily.

'They would just wait for the next victim.'

The nuns would watch from the windows, Peters said.

“If it wasn’t me, it was the next girl,” she said. “They would just wait for the next victim.”

Sometimes, her brothers would hear her screams from other parts of the schoolyard and they’d come running.

“It’s pretty sad when your little brothers are trying to help you … I think that’s what gave me the courage to keep going on.”

In middle school, she finally told her father about the assaults, and she took his advice to fight back.

“That’s why I’ve been a fighter,” she said. “I can’t be cornered.”

Desperate to learn Mi’kmaw

Peters had started at the school in kindergarten but then moved to Maine with her family.

There, she enjoyed school, picnics and homework.

She moved back to Elsipogtog three years later and was given the choice of going into Grade 3 or Grade 4. She chose Grade 3, thinking bullies wouldn’t bother her.

But she was still taunted because she could speak English after living in Maine. The other kids called her Yankee Doodle and teacher’s pet. Peters desperately tried to learn Mi’kmaw, spoken by the other kids.

She said she enjoyed learning and tried her best to be “OK” with the nuns.

“Of course you’ve got to be OK with them, they’ve got a f--king yardstick waiting there. Just slapping it on their hands.”

But she made mistakes too.

She once forgot her spelling book at home, and since her house was within walking distance, offered to run home to get it.

Her teacher slammed Peters’s head on a pile of textbooks.

“She stunned me. Shocked my body,” Peters said.

Forgiving helped

Life didn’t get easier after day school.

In high school, Peters said, she was sexually assaulted and gave birth to a son nine months later. She dropped out of Bonar Law Memorial High School in Grade 10.

Today, she lives with four of her nine grandchildren in Elsipogtog.

After her own childhood experiences, she’s always watching her grandchildren and won’t let them visit other people’s homes for sleepovers.

“You don’t know what sexual abuse went on there,” she said.

Peters also won’t wear dresses or bathing suits and doesn’t like people looking at her.

“Even now, when my boyfriend tries to hug me, I’m all ready to jump to hit,” she said.

In her late teens, she decided the best way to fight back was to forgive those who harmed her.

“I just forgave so I could carry on to live,” she said. “I became the toughest one after all.”

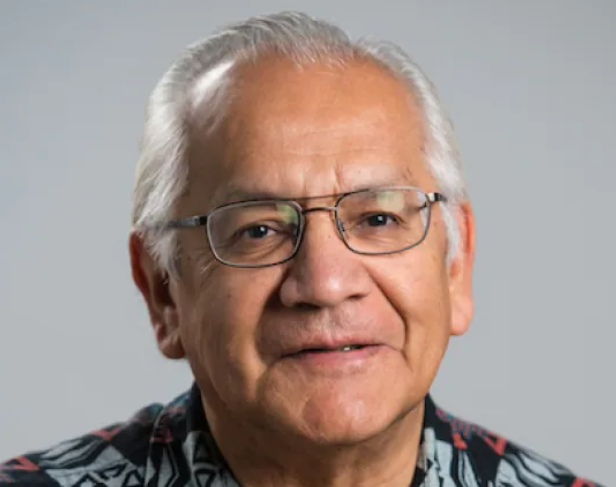

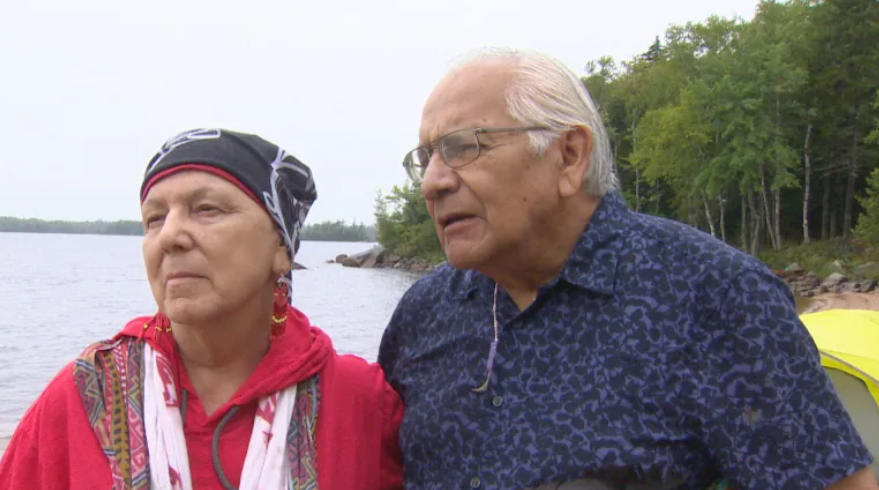

David Perley: Believing a lie

The morning David Perley started Grade 1, he arrived on the school grounds of Tobique Indian Day School 30 minutes early.

“I remember how excited I was the first day of school,” said Perley, who could see the school from his house in Tobique First Nation.

“I was practically running to school.”

When the bell rang, he and his friends formed a line before going inside; the boys were separated from the girls.

To keep things orderly, one nun stood at the front of each line, while another stood at the back.

Arriving at the Grade 1 classroom, students were marched inside to their assigned seats.

It was there the six-year-old was told he couldn’t speak the Wolastoqey language at school or on school grounds.

A nun with a leather strap would punish anyone caught breaking the rule.

“My excitement turned to fear,” said Perley, 72.

By the end of that morning, two of his friends had been strapped, and the other students were forced to watch.

“You’re six years old and your first language is Wolastoqey language,” he said. “And then you forget there’s a policy in place.”

After that first day, Perley begged his mom not to make him go back. But as a single parent after the death of Perley’s father, she thought there was nothing she could do.

Perley was at the school from 1955 to 1961.

“It was a long six years.”

‘Walking on eggshells’

Perley made it his mission not to get strapped, but it still happened about 10 times.

“I would remind myself, ‘You’ve got to be careful. I felt like I was walking on eggshells.”

He was once strapped for accidentally speaking his language while playing ball with his friends.

Another time, he didn’t understand a sentence in the Dick and Jane textbook he read aloud.

Although he could read the words perfectly, he had his ear pulled and was told he was stupid because he didn’t understand what the words meant.

“You remember those things because it was an attack on your self-esteem and who you are.”

But Perley was one of the lucky ones. The youngest of 13 kids in the family, he learned some English words from siblings before he was sent to school. His mom helped him with greetings like “Hello” and “How are you?”

'I was so afraid of making a mistake.'

School was more difficult for students coming in without any English. Perley watched nuns smack them with pointer sticks and pull their hair and ears.

Students were hit for mispronouncing words like “think” and “thank you,” because the “th” sound doesn’t exist in Wolastoqey.

“It’s hard when you transition from one language into another language and not have the same sounds,” Perley said. “You eventually make mistakes.”

He remembers one student who spoke no English and would just smile when a nun asked a question. He was strapped.

“I was so afraid of making a mistake,” Perley said.

‘Uncivilized, savage people’

The straps weren’t as bad as the verbal abuse.

“Every single day, the nuns would remind us how our ancestors were uncivilized, savage people,” he said. “Describing my language as gibberish.”

Perley’s family would remind him of the importance of his culture, but shame started to settle in.

“You start to believe, ‘Maybe they’re right.’”

Things didn’t get better in the public school system. After Grade 6, Perley went to Perth Middle School, about five kilometres away.

When his school bus arrived, he heard other students make what they imagined to be tribal sounds. Many non-Indigenous teachers and students called it “the Indian bus.”

“People staring at you and [saying], ‘Here comes the Indians.’”

During lunch hour, the non-Indigenous students sat in one area, the Indigenous students in another.

“Right off the bat, we’re segregated in different parts of the school.”

As he got older, Perley vowed to work on changing the school system.

Transforming a system

He became a chief and counsellor in Tobique and a senior official with the New Brunswick Department of Education.

Today, he teaches University of New Brunswick students about the Wolastoqey culture and language and gives a First Nations class at St. Thomas University in Fredericton.

In his talking circles, he tells Wolastoqi students and children where they come from.

He is also working on his PhD thesis, which speaks to his experience at the Tobique Indian Day School. He calls it a story of hardship, strength and resilience.

“We have something to be proud of,” he said.

Support is available for anyone affected by the lingering effects of residential school and those who are triggered by the latest reports.

A national Indian Residential School Crisis Line has been set up to provide support for residential school survivors and others affected. People can access emotional and crisis referral services by calling the 24-hour national crisis line: 1-866-925-4419.