It was every tourist town's worst fears come true. People were calling the local harbour a "toilet bowl," "disturbing," and "disgusting." Some visitors even threatened to boycott the community.

Panic was setting in at town hall. In one email to fellow council members, the mayor described the "brutal, nasty social media commentary" online and the "behaviour of a few misguided souls who have tainted our community."

It was hardly the type of talk to be expected during the lazy days of summer in Lunenburg, N.S., a tourist destination rich in history, beauty and a sense of pride in its designation as a UNESCO World Heritage site.

The tests done last August by teenage scientist Stella Bowles, best known for her work to clean up the nearby LaHave River, showed high levels of fecal bacteria in Lunenburg harbour — and sparked what the mayor would later call a "frenzy" in the community.

But a year later, the mood has shifted. While anxious officials at first tried to quell the concerns and worried Lunenburg's world-class reputation was at stake, there has since been a reckoning that has seen the town try to get to the bottom of the mystery of what's happening in its harbour.

"We are in some ways a showcase community, so people do have very high expectations," Mayor Rachel Bailey said in an interview. "We're not just a pretty place to visit, we're a working, very busy little town and we want to make sure we can continue to be both."

Emails between town and elected officials, obtained by CBC News through freedom-of-information laws, along with interviews and an examination of council minutes and reports show how Lunenburg has grappled with the problem.

Lunenburg harbour is not intended for swimming. But the fecal bacteria levels are so high in spots there is concern boaters, kayakers and other paddlers could get sick if their arms or legs are in the water.

This summer, the town has hired environmental group Bluenose Coastal Action Foundation to test the water weekly. It's also commissioned a $75,000 study to do an overview of the waste-water treatment plant, which was built in 2003 and pipes treated sewage several hundred metres to the harbour.

It's a lesson not exclusive to Lunenburg, which has a population of 2,300 but fewer than 1,000 taxpayers. Sorting out sewage treatment and disposal problems is one of the most trying and expensive issues a community can face.

"We've let the development of our towns and coastal cities get ahead of our investment in these treatment facilities, to the point that we have these kinds of unpleasant occurrences," said Bruce Hatcher, chair in marine ecosystem research at Cape Breton University.

Hatcher said fixing the problems is expensive — and that it's not uncommon for fecal matter to be found in Nova Scotia harbours.

The tourists haven't fled Lunenburg, at least not yet. Giant RVs still cruise past stately heritage homes, and the place bustles with visitors.

But Hatcher argues the town should take the "threat to its tourism business" and use it as an argument that it deserves the type of federal funding other communities have used to clean up their ports and harbours.

The discovery of the bacteria levels in Lunenburg harbour brought to the forefront other complaints from locals — and soon town officials found themselves battling confusion and overlap between different problems.

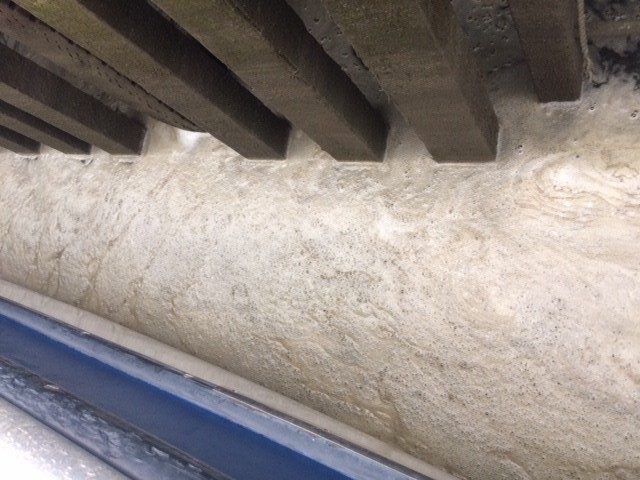

For at least a decade, fishermen and tour operators at the Inshore Fishermen's Wharf have complained about the town's waste-water treatment facility outfall, which sits underneath where they dock their boats.

Bill Flower, one of the tour boat operators, has been vocal with his concerns about the "sludge" coming out of the pipe. He even flung some of it at the mayor last August, and there's a one-year peace bond forbidding him from going near her.

"It's disgusting," he said of the substance.

Town staff have long tried to determine what exactly it is. The consensus seems to be that it's residual polymer — a synthetic substance that clumps particles together during the water treatment process. Once it hits the harbour, it coagulates with other matter and turns into the brown sludge Flower describes.

Part of the worry for the town last summer was when people began to assume the fecal bacteria and the outfall went hand in hand. Right now there isn't a way to say that for certain — but it's part of what's being investigated.

"I know it's easy to point the finger at the sewage treatment plant, it's this big, obvious source of sewage," said Shanna Fredericks, assistant director of Bluenose Coastal Action Foundation.

"But the reality is it's just one of many, many sources."

She said there's a list of possible culprits. The tide could be washing in contamination from a neighbouring community, Garden Lots, where raw sewage is piped directly from some homes into the harbour. The problem could also be stormwater runoff, combined sewer and stormwater pipes, fertilizers, wildlife, pet or livestock waste, or problems at the treatment plant.

When it rains heavily, or if there's some kind of system failure at the plant, there is a hydraulic system in place that bypasses the water-treatment system and puts raw sewage straight into the harbour. This kind of system is in almost every treatment facility, because it stops excess water from backing up into people's homes.

But Bailey said the town wants to be sure it works properly, which is why it's decided to study the 15-year-old waste-water treatment plant.

There's also been ongoing maintenance on the waste-water treatment plant itself.

Emails show problems with various parts of the facility, including the rotary press and sludge holding tank. In November, council had to find $82,000 for unanticipated repairs.

"Sewage treatment is a messy business. It seems like an obvious statement, but it does take a toll on equipment," Bailey said. "Whether we expected to be dealing with it to the tune that we are, the answer would probably be no."

Sewage treatment infrastructure in Lunenburg has cost the town millions.

Last summer, it put new pipes under two main streets to separate the sewage and stormwater lines. The aim is to reduce pressure on the treatment plant by directing less water from heavy rainfalls to the facility.

But it was Bowles's tests that prompted the town to begin testing the harbour weekly for enterococci — what Health Canada says is the most appropriate indicator of fecal contamination in marine water.

"I think the frenzy started with the testing Stella Bowles did because it was such a radical number that she presented us with, and that was alarming," Bailey said.

"But they were a bit of an anomaly and we can't explain that to this day — and wouldn't try to."

Emails show Bowles herself was a source of anxiety.

On Aug. 15, when the girl did an interview on CBC Radio's Information Morning, Bailey sent an email to the town's communications person, Heather McCallum, saying the interview "was potentially far more damaging to the community than previous media coverage."

Later that day, McCallum responded: "I haven't yet heard Stella's interview today, but let's proceed regardless."

Employees from the water utility began to gather samples at five sites and sent them off to an accredited laboratory to be tested.

Three of the sites stayed below Health Canada's guidelines for secondary recreational activity, such as boating. The acceptable levels for such activity is 175 enterococci/100ml.

Fishermen's Wharf, however, was above those levels significantly for four of the six weeks tested — as was the fifth testing site, home of the new and much anticipated Broad Street boat launch. Both sites are closest to the back of the harbour.

"The water quality at the Inshore Fishermen's Wharf is not good. Full stop. It's not good, it's not been good for a long time and we know that. What to do about that has been a quandary for just as long," Bailey said.

The town did a study that recommended extending the outfall further into the harbour and away from the wharf, but because of the cost it was put on the capital planning list for 2020 or 2021.

While emails show there was talk of having the final test results from last summer analyzed, which might have shed more light on the cause, the mayor said that never happened.

"I don't think the information was collected in a way, as systematically or scientifically, to enable that to happen," she said.

Along with the $16,000 for the testing, the town has given Bluenose Coastal Action an additional $3,000 to create a harbour advisory group, bringing together business owners, government and local residents to address some of the issues.

Fredericks said when it comes to bacteria testing, there's a lot of variability.

"You really need a long-term data set to make any real conclusions," she said.

Along with the weekly testing, Bluenose Coastal Action will twice test the harbour after significant rainfall, as well as test sediment at the bottom.

So far this summer, tests have shown much higher than acceptable levels at Fishermen's Wharf. Results from Zwicker Wharf and the Broad Street boat launch have varied but spiked last week, prompting the town to warn that people "should exercise caution during water-based recreational activities in these areas."

Bailey said because of concerns over the quality of the water, the town hasn't been promoting its new $270,000 Broad Street boat launch — although she said that hasn't stopped people from using it.

"Ideally they'd all be crystal clean and pure and wonderful and we wouldn't have to give them a second thought, but that's not been the case," she said.

The waste-water treatment plant study, which will start in a few weeks, will look at if the existing process is suitable for what it's doing, whether the waste-water quality can be improved, and ongoing odour issues.

Part of the smelly problems at the plant should be resolved with the new $1.1-million biofilter system being installed this summer, thanks to help from provincial and federal governments.

The potential results of the study are already a financial worry, and Bailey said if major changes are recommended, the town will again have to reach out to other levels of government for help.

"We truly do want to be accountable and up front with what we’re dealing with, and we’re hopeful we’ll get to a better place this summer," she said.