March 29, 2018

The preteen girls would take turns with the towel in the bathroom of St. Anne’s Indian Residential School.

One at a time they would wrap it around their throats and pull it tight.

“We called it getting high. We’d get dizzy, lightheaded,” one of them said nearly two decades later, on Aug. 3, 1993, during an interview with Ontario Provincial Police investigators in Room 251 of the Howard Johnson Hotel in London, Ont.

“We looked forward to it,” said the residential school survivor, whose name is redacted in the OPP transcript. “It was an escape.”

The woman, by then in her mid-30s, was describing her horrific nine-year stay at the school on Fort Albany First Nation, near the James Bay coast, as part of an indecent assault investigation of one of its former nuns.

What she needed to escape, she told investigators, were the constant strappings and whippings, and the sexual assaults by a man she knew only as “the gardener.”

“This shouldn’t have happened to us. They’re God’s workers, they were to look after us.”

The transcript of the interview is among thousands of pages of OPP records from a sprawling investigation into abuse at St. Anne’s obtained by CBC News.

The investigation began on Nov. 9, 1992, after Fort Albany First Nation Chief Edmund Metatawabin presented evidence to police following a healing conference attended by St. Anne’s survivors. Over the next six years, the OPP would interview 700 victims and witnesses and gather 900 statements about assaults, sexual assaults, suspicious deaths and a multitude of abuses alleged to have occurred at the school between 1941 and 1972.

Investigators identified 74 suspects and charged seven people. Five were convicted of crimes committed at the residential school

But from 2008 to 2014, the federal government omitted references to the OPP investigation, including the convictions, from the official St. Anne’s record, known as the school narrative, used during compensation hearings created by the 2006 Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement.

The school narrative is a key piece of evidence for compensation cases heard under the agreement’s Independent Assessment Process (IAP). Adjudicators who hear survivors’ stories can refer to the school narrative as one way to determine the veracity of a claim.

In the case of St. Anne’s, adjudicators relied on a school narrative that said there was no record of sexual assaults or student-on-student abuse cases. The school narrative referred to only four recorded cases of physical abuse found in St. Anne’s records in the Indian Affairs Department archives.

Yet, the federal Justice Department obtained the OPP files from the investigation in 2003 after a group of St. Anne’s survivors filed an abuse lawsuit in Cochrane, Ont., against Ottawa and the Catholic entities that ran the school. The case ended with a settlement.

Indian Affairs also included a reference to the OPP case and the convictions in the St. Anne’s school narrative used during the Alternative Dispute Resolution process for settling compensation claims, which ran from November 2003 to September 2007, when it was replaced by the IAP.

A 2014 ruling from the Ontario Superior Court forced the Harper government to disclose the OPP files and documents from the civil action in Cochrane to St. Anne’s survivors.

The school narrative used in the IAP hearings grew from 12 pages to about 1,200 pages referring to more than 12,000 documents.

Litigation has continued following the ruling as it emerged some St. Anne’s survivors lost compensation cases because adjudicators doubted the veracity of their claims as a result of the incomplete record.

Survivors want the Ontario Court of Appeal to force the government to turn over testimony transcripts from the Cochrane hearing. They are also seeking a process to deal with St. Anne’s claims that were heard before the government turned over the OPP files.

Some survivors have spoken out and written books about their experiences at the school, including, in some cases, being shocked in a homemade electric chair. The OPP investigation also received national media coverage at the time.

However, the investigation files obtained by CBC News contain the raw evidence gathered by the OPP during its investigation into one of the most notorious residential schools — evidence that has never been shared with the public.

While the names of the victims and perpetrators are largely redacted from the OPP files, they reveal the depth of abuse and torture at the school.

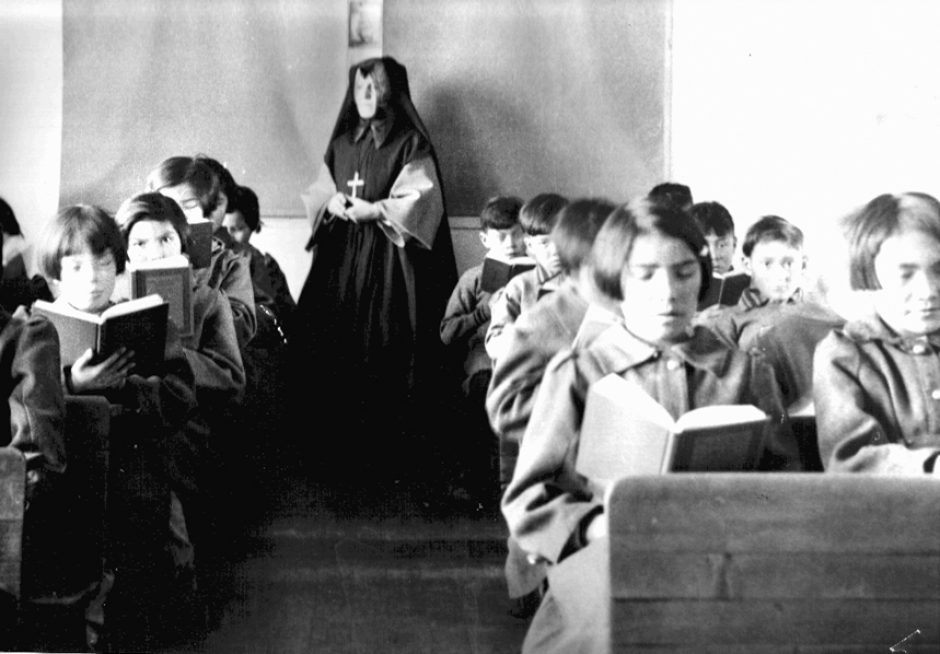

This school was run by the Catholic orders of Oblates of Mary Immaculate and the Grey Sisters of the Cross from 1902 until 1976. The federal government began funding the school in 1906.

Only a small shack remains of St. Anne’s today. The school, the nuns’ residence and the rectory burned down separately over the past 15 years.

The site, which is owned by the band, is now a water treatment plant and a storage depot for housing material.

In the summertime we go swimming and play German ball. We play baseball and we play soccer. We fight in the long grass. We use some branches to kill dragonflies.

(From a project titled We Live at School by Grade 3 and 4 students at St. Anne’s in March 1972. The piece was found in the OPP files.)

All of the survivors interviewed by the OPP during the investigation described suffering or witnessing multiple abuses — physical, sexual and psychological.

This was the case with the survivor interviewed at the Howard Johnson Hotel.

At one point in the transcript she described a straitjacket.

She told investigators it was a “greyish beige colour” and made from tough material “like denim,” with zippers down the back and front. The sleeves had fringes to bind the arms together across the front and bindings to secure the hands together behind the neck, she said during a second interview with OPP on Aug. 10, 1994.

Sometimes students would be tied to the bed, she said.

“It depended on how bad you were acting up.”

She remembered one time, while having her first period, she resisted a nun who was rubbing her breasts and stomach before moving down between her legs.

“A confused angry look came over her face,” she told investigators. “That’s when she said, ‘You know the devil’s inside you,’ and that they had to get the devil out.”

The nun then restrained her in the straitjacket and continued to sexually assault her, she said.

“She didn’t even mind the mess or anything. It was almost like she got a thrill out of it or something,” the survivor said.

“Listen, I don’t want to talk about this anymore.”

The nun was never charged.

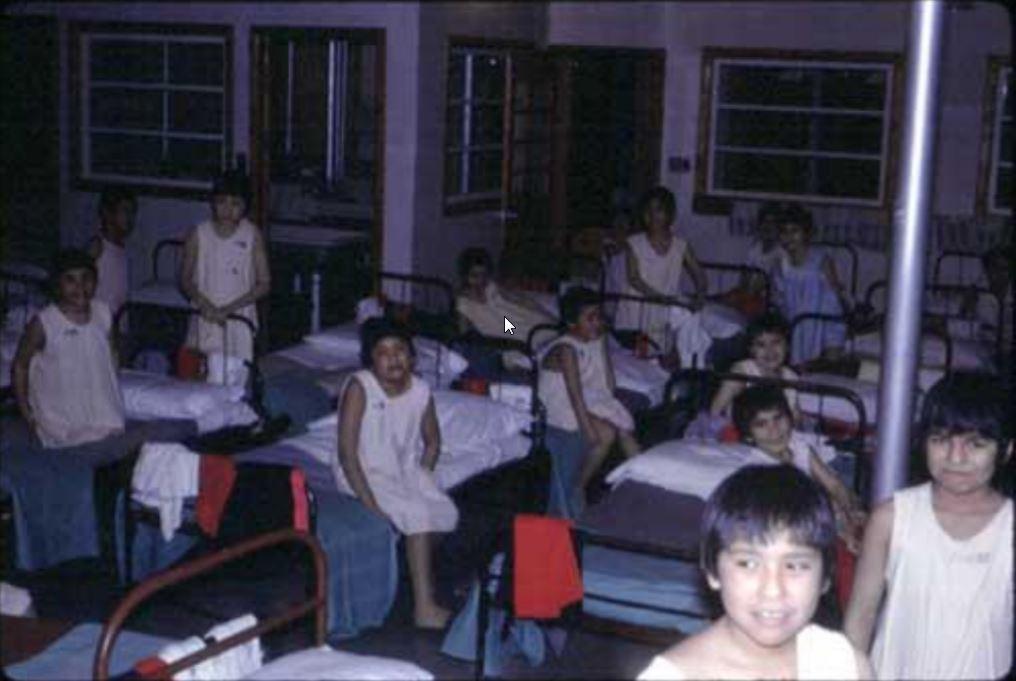

Nuns, priests and lay brothers would hit students with large straps, small whips, beaver snare wire, boards, books, rulers, yardsticks, fists and open hands, survivors told investigators. Sometimes students were locked away in the dark basement for hours at a time.

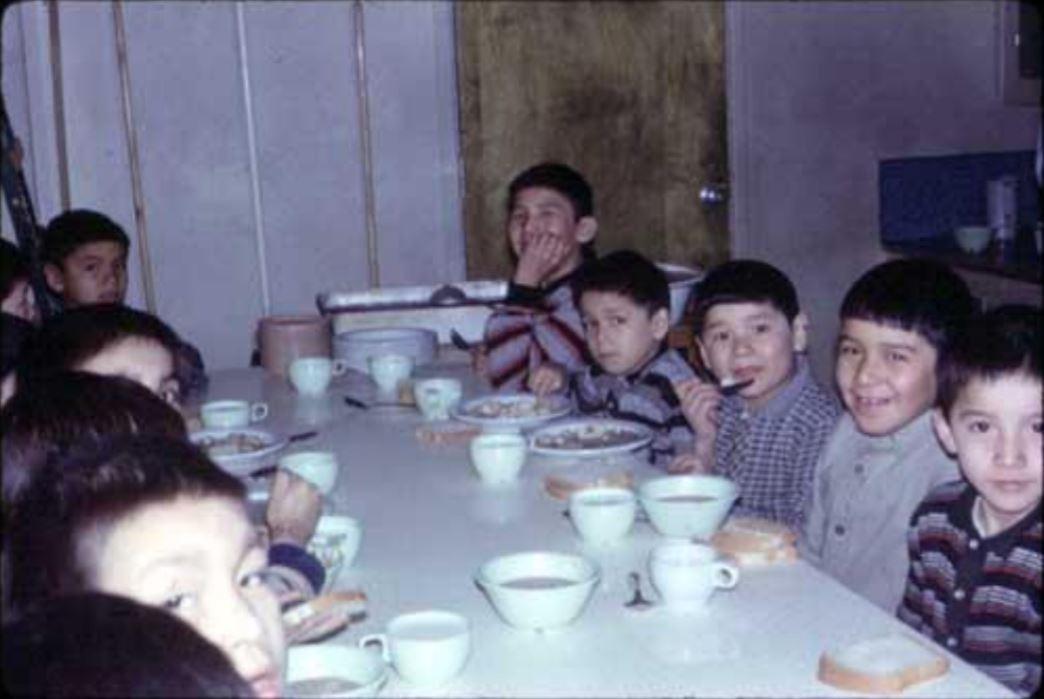

They also told investigators about being force-fed porridge, spoiled fish, cod liver oil and rancid horse meat that made students sick to the point of vomiting on their plates.

They said they were often forced to then eat their vomit.

There were numerous allegations of sexual abuse involving nuns, priests, lay brothers and other staff, ranging from fondling and forced kissing to violent attacks and nighttime molestation.

One survivor, who was in her 50s at the time of her August 1993 interview with OPP investigators, said she remembered a staff member who targeted five girls for sexual abuse during her time at St. Anne’s, which lasted from 1951 to 1955. The survivor, who began attending the school at age 11, said the staff member would take a different girl every night.

She said she once snuck upstairs with her cousin and a friend to the boys section and peeked through the door. She said two boys were lying naked on separate beds.

“I remember hearing them boys, screaming,” she told investigators at the Taykwa Tagamou Nation band office near Cochrane, located about 120 kilometres north of Timmins.

We live here / At St. Anne’s School

Some of us / Are from far away

Like Winisk and Moosonee

And some of us are only / From Fort Albany;

We like school,

But sometimes we are sad;

We are wanting to see

Our families / At home.

Maybe they are wanting

To see us / Too.

(We Live at School, Grades 3 and 4 at St. Anne’s Indian Residential School, March 1972)

A survivor who attended St. Anne’s in the 1960s said an older student once lured him into the basement with the promise of a surprise.

“I thought it was gonna be a good surprise like a cake or something,” he said, according to transcripts of his statements to police in July 1993 and November 1994.

The survivor had described a life of harsh punishment at the school that was made worse by his dyslexia. He said a staff member once broke a yardstick across his back.

But nothing prepared him for the brutal surprise waiting for him in the basement.

He remembered between 30 and 50 students were gathered there. After he was beaten by about 15 students, six of them then held him down and tied his hands and feet together. They wrapped a rope around his neck. The students started playing tug of war with him, with one group pulling at his feet and the other pulling at his neck, he told the OPP. He said he kept his neck from breaking by grabbing on to the rope with his bound hands.

Then one of the students told the others to throw the rope attached to his neck over a pipe running across the ceiling.

“I remember being pulled up once and when I was off the ground I blacked out,” he said. “When I came to, all the boys were gone. The rope was taken off by ... the supervisor.”

He said he was taken to the hospital, given ointment, and returned to class with a neck collar over some gauze.

Neither the supervisor who found him nor the nun who treated him at the hospital ever asked him what happened, he said.

The OPP contacted the former supervisor, but he claimed he could not remember the attack. Investigators also found the former nun who worked at the hospital. She said she could not remember the boy.

The investigation record is replete with allegations of staff actively participating in or facilitating student-on-student physical and sexual abuse. There are also stories of student-on-student gang rapes and beatings. Some of the suspect profiles reveal student abusers were often themselves abused.

In one OPP interview, a male survivor recalled that during the 1956-57 school year a nun ordered eight boys to hold him down as she strapped him 27 times.

In another interview, a woman who attended St. Anne’s between 1963 and 1971 described how a school supervisor would pick on certain children she considered slow and how she humiliated a girl by forcing her to wear toilet paper around her neck to class.

“It got to the point where older girls would beat up the younger girls,” she told the OPP. “I beat up my younger sister … We did this to get rid of our frustration.”

Sometimes they put wax on the floors so they are shiny and then they look very nice. We can slide on the floors when the wax is on.

(We Live at School, Grades 3 and 4 at St. Anne’s Indian Residential School, March 1972)

Even after the 2014 court decision forcing Ottawa to turn over the OPP files to survivors, the Justice Department continued to use the incomplete narrative.

One survivor, known in court records as H-15019, lost his compensation claim because he wasn’t believed. During his IAP hearing in July 2014, Justice Department lawyers relied on the incomplete school narrative despite possessing proof a priest mentioned in the compensation claim was a “serial sex abuser,” the survivor later alleged in court documents.

The court granted him a new hearing and he eventually secured his compensation.

The federal government’s handling of St. Anne’s-related documents is part of a pattern, according to filings before the Ontario Court of Appeal in the St. Anne’s disclosure case.

The survivors say the federal government has a history of “reluctant, contradictory and inconsistent disclosure of documentation of abuse in residential schools.”

They provide several examples, including a case from 1998 where a former student of Port Alberni Indian Residential School on Vancouver Island sued Ottawa over abuse he suffered at the school. During the case, which reached the Supreme Court, Indian Affairs claimed it only knew of five cases of sexual assault at residential schools across the country over a 50-year period.

However, between 1994 and 1996, the department had identified a possible 91 cases of physical and sexual abuse at the schools and asked the RCMP to investigate.

In 1994, the Indian and Northern Affairs Department refused to hand over documentation to an RCMP task force investigating cases in British Columbia, forcing the Mounties to obtain multiple search warrants for the department’s head offices in Hull, Que., according to the Court of Appeal filings.

Even the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) faced difficulty obtaining records of criminal convictions related to residential school abuse from Indian Affairs. The department told the commission it didn’t have them. The TRC concluded otherwise but was forced to complete its final report without them.

One night we were playing in the junior’s side too and we were very loud. We were supposed to be sleeping. Mr. Ross came and after the watchman and Mr. Croteau. Mr. Ross yelled, “Quiet!” very loud. He scared us when he yelled and everybody went to bed. Then we started playing again and the [redacted] knocked at the door for nothing. After, he kicked Mr. Glen’s door. We told Mr. Glen it was [redacted] that knocked. He spanked [redacted].

(We Live at School, Grades 3 and 4 at St. Anne’s Indian Residential School, March 1972)

The description of the electric chair varied but it appeared to have been used between the mid-to-late-1950s and the mid-1960s, according to OPP transcripts and reports. Some said it was metal while others said it was made of dark green wood, like a wheelchair without wheels. They all said it had straps on the armrests and wires attached to a battery.

“I can remember we tall girls were in the girls recreation group and [redacted] came in and had the chair with him,” a survivor said in an interview with OPP on Dec. 18, 1992. “Then one by one [redacted] and [redacted] would make the girls sit on the electric chair. If you didn’t want to [reacted] would push you into the chair and hold your arms onto the arms of the chair.”

The survivor told the OPP she was forced to sit on the chair in 1964 or 1965.

“I was scared,” she said. “[Redacted] hit the switch two or three times while I sat in the chair. I got shocked. It felt like my whole body tingled. It’s hard to describe. It was painful.”

She then started to cry.

The OPP records indicate one former student said she was put in the chair and shocked until she passed out. Another said he was told he had to sit in the chair if he wanted to speak to his mother.

One survivor, in an interview with police on Feb. 27, 1993, said two lay brothers made the students stand in a circle holding on to the armrests as one student sat in the chair. One of the brothers flicked the switch.

“It felt like a whole bunch of needles going up your arms,” the former student said. “The two brothers started to laugh … and shocked us again. I then started to cry because it really hurts.”

I was almost asleep / In that night;

I see the bright moon / In the sky.

The moon was very high

And I think of my mother

In Winisk / With my family.

Maybe in this month / I will see them,

But they are very far

Away from here.

I am in school / In Fort Albany

But when I see them in July

I am very happy

- [Redacted]

(We Live at School, Grades 3 and 4 at St. Anne’s Residential School, March 1972)

There were stories about the death of a boy who fell from a swing in 1933. Another boy drowned after falling through the ice while skating in the early 1940s. One survivor told police a boy was beaten to death in the 1940s or '50s for stealing a communion wafer.

Then there was the disappearance of three boys: John Kioki, 14, and Michel Matinas, 11, both from Attawapiskat, and Michael Sutherland, 13, from Weemisk.

The trio left St. Anne’s with a fourth boy in the early morning hours of April 19, 1941, but he returned to the school because he was told by the others he was too young to make the journey to Attawapiskat.

The boys had planned their escape in whispers at night, according to various interviews conducted by the OPP. They told the other students to keep the plan quiet as they gathered leftovers from meals to store in a flour bag they kept hidden for their escape. The boys also had a bow and 10 arrows to hunt rabbits and partridge.

The boys ran away because they were sick of being strapped, said a former classmate, who also told police the boys snuck out at 5 a.m. in sock feet, holding their boots. He said he and four other boys snuck out of the school three hours after the first group. It was foggy that morning and it took them some time to find the first group’s trail that led north on the Albany River.

“The river wasn’t open yet but it was getting wet on top of the river,” he told the OPP.

The group of five returned to the school after another student caught up with them and told them a priest had noticed they were gone and ordered them back.

A St. Anne’s staff member was later sent out to look for the missing trio but turned back after it got dark. A storm hit on the second day of searching.

The RCMP and an Indian Affairs official were not informed of the boys’ disappearance until weeks later, on June 6, 1941.

Eventually some of the local Cree who were out hunting said they came across a small wigwam and arrows about 16 kilometres away near the Chickney River.

The boys were assumed to have drowned. Their bodies were never recovered.

“The whole affair is regrettable and the parents’ indignation is understandable,” an RCMP constable said in a dispatch to superiors on June 27, 1941. “There does not seem to be anything further that can be done at this late date. In view of this, the file is being considered closed.”

A public inquiry was held the following year and reached the same conclusion.

We wrote “We Live at School” so that other children that do not live in school will know what it is like. We have a big school and many people work here. There are about 220 children at the school and about 120 live here. The rest live at home in the village.

(From We Live at School, Grades 3 and 4 at St. Anne’s Indian Residential School, March 1972)

The legacy of St. Anne’s is still felt from Moosonee to Fort Albany First Nation to Attawapiskat and to Peawanuck, which used to be known as Winisk but was destroyed by a flood.

Surrounded by deaths and disappearances, constant fear and violence, the survivors interviewed by the OPP spoke about attempted suicides, struggles with addictions and broken lives.

Lives crippled by a childhood living at school.

“I craved ... and was sick for love,” a survivor told an OPP investigator.

The five people convicted following the OPP investigation included:

Ann Wesley, a Cree nun born in Attawapiskat, who attended St. Anne’s as a child, was convicted of three counts of common assault, three counts of administering a noxious substance, and one count of assault causing bodily harm. She received an 11-month conditional sentence.

Jane Kakaychawan, an Ojibway nun born in Ogoki Post, Ont., who as a child attended the McIntosh Indian Residential School north of Vermilion Bay, Ont., was convicted of three counts of assault causing bodily harm. She was given a six-month conditional sentence.

John Moses Rodrique, a cook and later employed by Indian Affairs, pleaded guilty to five counts of indecent assault. He was sentenced to 18 months in jail.

Claude Lambert, a child-care worker at St. Anne’s, pleaded guilty to one count of indecent assault and was sentenced to eight months in jail.

Marcel Blais, who worked in the kitchen, pleaded guilty to one count of indecent assault on a male. He did not receive jail time.

This story is part of our project Beyond 94: Truth and Reconciliation in Canada.