May 21, 2018

The More than Words series about B.C. Indigenous languages is produced in partnership with the Reporting in Indigenous Communities course at UBC's Graduate School of Journalism.

Listen to the More than Words special on CBC Radio Monday, May 21 at 4 p.m. local time.

Sto:lo language teachers take fluency into their own hands

A chorus of little voices cries out, “Éy swáyel, Mrs. Kelly!”

Grade 1 students in Chilliwack, B.C., are wishing their teacher Lauralee Kelly “Good Day” in Halq’eméylem, the Coast Salish dialect of Stó:lō communities across the Fraser Valley.

As a teacher and language learner, Kelly faces a steep uphill battle.

Chronic underfunding by provincial and federal governments has hobbled the immersion programs Stó:lō communities need in order to revitalize Halq’eméylem.

Now, there is only one actively fluent speaker.

“There’s been so much loss,” said Kelly. “We need to become fluent with our last remaining elder, who’s willing to teach it, so we don’t lose everything these ancestors left for us.”

Along with a small group of teachers, Kelly has resolved to become fluent and carry Halq’eméylem forward. To do that, they need sustainable funding.

Both the B.C. and federal governments have promised unprecedented support for Indigenous languages. But whether 2018 will bring the support frontline language leaders need will depend on where and how the money flows.

‘We need to get ourselves fluent.’

The loss of generations of Halq’eméylem speakers is a direct consequence of Canada’s residential school system, which included St. Mary’s school near Chilliwack.

“My mum was one of the residential school survivors who knew the language but didn’t pass it on because of ... [the] beatings she took for it,” Kelly said.

By the time St. Mary’s closed in 1984, elders and linguists had already recorded hundreds of hours of storytelling and developed a curriculum for a teacher training program.

The Shxweli program began in the 1990s and brought aspiring Halq’eméylem teachers together with a handful of fluent elders for immersive learning.

Kelly is one of around 20 people accredited through Shxweli. None of the graduates is fully fluent, however, and when funding became sparse, teacher training fizzled.

Now, there is just one Halq’eméylem teacher under the age of 30.

Jessica Malloway, 25, kneels over flashcards she created for students at Squiala Elementary School. Soon, she will hurry to another school nearby in order to meet full-time hours.

“I do teach basic Halq’eméylem,” said Malloway. “But getting to more complex sentences, I’m starting to forget ... We need to get ourselves fluent.”

‘You’re battling your own communities for the same penny.’

Patricia Raymond-Adair is intimately acquainted with the herculean nature of language revitalization.

For almost a decade she managed the Coqualeetza Cultural Education Centre, which supports language and cultural programming in Stó:lō communities.

“We have a passion and a belief in what we’re doing but we’re losing people, because they’re tired of the fight,” said Raymond-Adair.

“I burned out, too.... You’re battling your own communities for the same penny.”

Annual federal funding of $132,700 is stretched to cover all of the Coqualeetza centre’s expenses, including wages and rent. Raymond-Adair kept programming afloat by applying for short-term grants of around $15,000 from the First Peoples’ Cultural Council — the Crown corporation responsible for distributing funding for Indigenous languages in B.C.

“Very little [funding] gets to the grassroots, to the language speakers and teachers,” Raymond-Adair said.

“Their wages are not on par with the administrative wages, where the money is funnelled through.”

Tammy Bartz, the administrator at Squiala First Nation, applied for an FPCC grant around 2005, after community members requested Halq’eméylem classes for adults.

“It took me a couple of years. I finally got a grant, which was an enormous amount of paperwork,” said Bartz.

Classes ran once a week for around a year.

“It’s not enough,” said Bartz. “What nationality has to pay to learn their language?”

Promise of new funding

In its 2018 budget, the B.C. government pledged $50 million for Indigenous languages. Federal legislation is also expected later this year.

For the first time, multi-year funding is available. The FPCC is accepting proposals for grants up to $100,000 per year for three years. It could be the boost immersion programs need.

But the application process remains arduous for communities strapped for time and resources. Lengthy proposals were due on April 25 — around six weeks after the FPCC published details online.

“We are very cognizant of the challenges that model creates,” said Language Programs Manager Aliana Parker.

She added the FPCC is exploring how to increase support for communities through the process.

Until there is funding to support a cohesive push for Halq’eméylem revitalization that reaches across all Stó:lō communities, Lauralee Kelly, Jessica Malloway and a handful of language leaders must take fluency into their own hands.

Kelly and Malloway are planning to convene a group of teachers to learn with the last actively fluent Halq’eméylem speaker — 79-year-old Elizabeth Phillips.

“I haven’t had time to meet with [Elizabeth], but she would probably start crying,” said Kelly.

“That’s her dream, to see some fluent speakers out of everything she’s done for the last 40 years.”

Kelly knows of around 12 teachers interested in joining the budding fluency group.

“If we did some kind of summer program, where all the language teachers met as if it were a job ... eight-hour days, five days a week, it would be awesome,” said Malloway.

Because of the barriers to accessing funding, the group at Coqualeetza didn’t apply for an FPCC grant this year.

But Kelly said getting together to speak Halq’eméylem is an important step no matter what — both toward fluency and, she hopes, toward creating a Halq’eméylem immersion school, where she could teach as a fluent speaker.

“Deep down, that feeling of why I’m doing what I’m doing, it’s just been woken up ... I do have big dreams for our people.”

Taking Skwomesh beyond the classroom

Four years ago, a report on the status of B.C. First Nations languages listed Sk̲wx̱wú7mesh sníchim, or Skwomesh, as "critically endangered," having only seven fluent speakers remaining.

But that’s starting to change.

Passersby walking through Simon Fraser University’s downtown Vancouver campus over the last academic year might have been lucky enough to overhear a small group of people conversing in Skwomesh.

Those speakers were students enrolled in the second cohort of an immersive Skwomesh language course, co-offered by SFU and the Squamish language non-profit Kwi Awt Stelmexw. They graduated last month.

But leaving the immersive classroom environment behind presents their biggest challenge yet. Swo-wo Gabriel (Billy), who graduated in the first cohort a year ago, knows this all too well.

“It'd be easier if there was more language in our daily lives.”

The problem is that, even among the Squamish Nation’s 6,000 members, there are only a handful of skilled speakers. Beyond the small community, the language is mostly drowned out in a sea of English. That’s a situation the graduates themselves will need to change.

'I didn't feel like I had anybody to talk to.'

For Swo-wo, using Skwomesh in daily life first involves using it at home.

“Our main goal is just to get language, our Skwomesh language, to start being spoken in the homes. At home. With kids. With families.”

To do this, he surrounds his two-year old daughter with as much Skwomesh as possible. Bedtime stories are a good place to start.

“My daughter loves reading children’s books,” he said.

“I translate [from English to Skwomesh] when I read her books.”

His daughter can’t read yet, but enjoys looking at the pictures and hearing Skwomesh. Swo-wo expects she’ll be reading for herself soon, and he’s hoping to work with an illustrator to develop Skwomesh children’s books that would be ready for her when she does.

But Swo-wo hasn’t left the classroom fully behind.

After graduating, he was selected to become a teaching assistant for the second cohort. That’s meant he’s been able to work immersed in the language, a major draw to the job.

“The main reason I said yes wasn't to teach new people, it was to create more speakers that I could talk with.”

But for others in last year’s cohort, including Carey McReynolds, the opportunity to be fully immersed in the language is rare.

McReynolds is a teacher at the Capilano Little Ones School, an elementary school run by the Squamish Nation. Born in Alberta, she moved to her mother’s reserve in North Vancouver during high school. It was there she started learning more about Skwomesh language and culture. She said taking the Skwomesh immersion class was a natural continuation of her learning.

Being isolated from other speakers has been her biggest challenge since graduating. She doesn’t get many opportunities to spend time talking with the few other Skwomesh speakers in the community. While she teaches her young students some Skwomesh, they’re unable to maintain long or complex conversations.

“I’m teaching simple words right now, not enough to stay sharp in the language,” she said.

The feeling of isolation isn’t unique to McReynolds. Even Char George, Swo-wo’s co-teacher in the immersion program, has struggled with language loneliness.

“I went crazy last year, I didn't feel like I had anybody to talk to,” said George.

“Then I would listen to the recordings and my co-worker would laugh. She'd be like, ‘It sounds like you're having a conversation with somebody.’ I would talk back-and-forth if I just had headphones on, which is cool because it's my late great-uncle I was listening to.”

'They're starting to feel that ripple effect now.'

Last month, another 15 Skwomesh language speakers left the classroom behind, raising the number of program graduates to 30. That number doesn’t factor in pre-existing speakers and children now being taught Skwomesh as a first language at home.

Kwi Awt Stelmexw, the non-profit behind the program, hopes that by 2028 there will be more than 170 fluent Skwomesh speakers.

According to Swo-wo, those speakers will be at the forefront of the language’s reawakening.

“I can’t tell a lawyer what language he needs to use in Skwomesh — a lawyer needs to get fluent and figure it out. We need more people from different walks of life to become fluent. That will bring out more language we haven’t used in a long time.”

Char George likes to think of the language’s growth using a metaphor.

“We're that pebble that got thrown in and made the ripple, and now it's going out to the community and they're starting to see it. They're starting to feel that ripple effect now.”

That ripple is spreading quickly. According to George, there’s plenty of interest in next year’s program, particularly from youth, which is good news for those striving to speak Skwomesh beyond the classroom.

“I'd love if there was a lot of young people next year, then they have the whole rest of their lives to learn.”

Hailhzaqvla in the city

Elizabeth Wilson sits in front of a projection screen showing the tonal Hailhzaqvla (Heiltsuk) alphabet, surrounded by eager students from across Metro Vancouver.

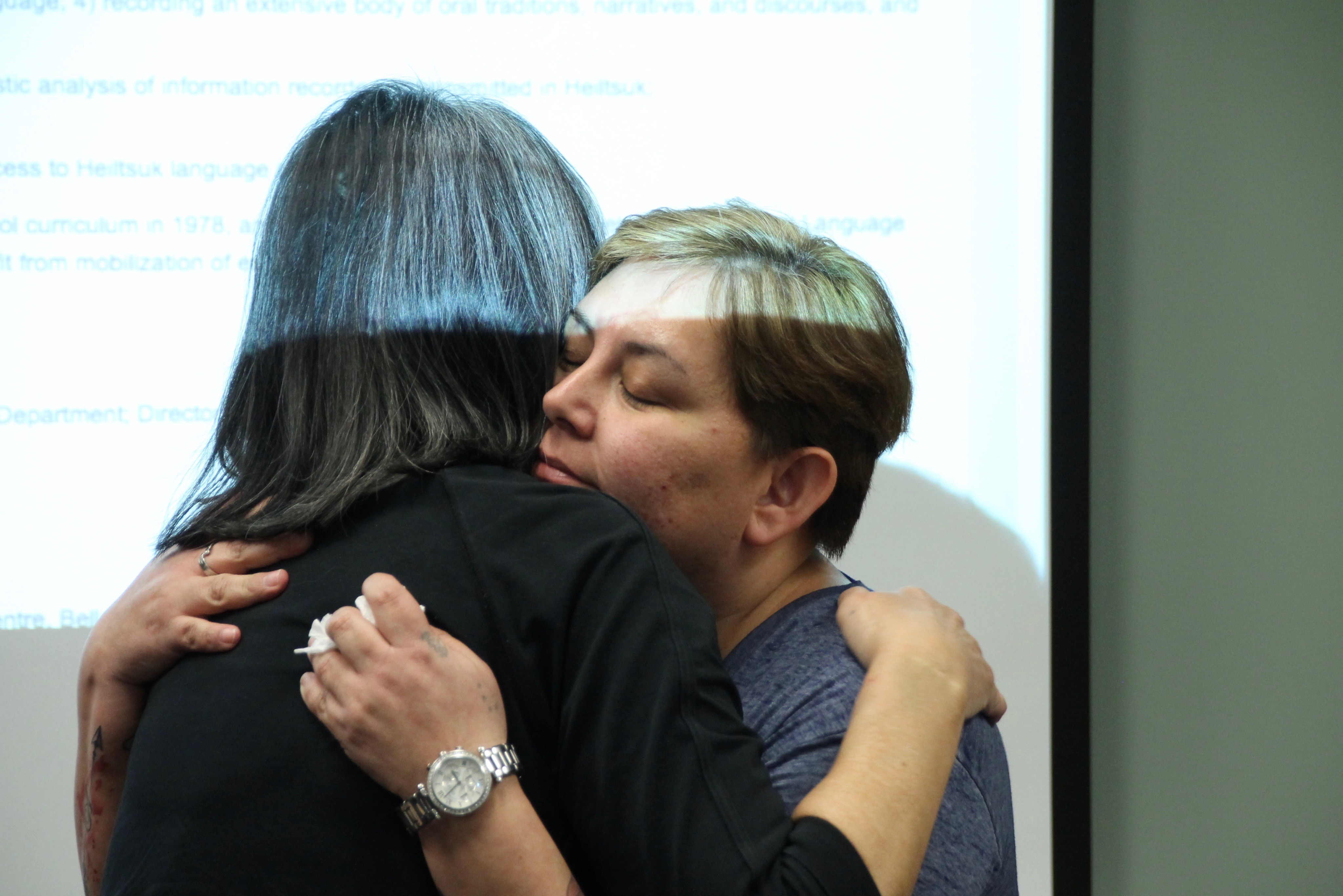

It’s late March, and 13 participants have come to her first language class, ranging in age from elders to youth. Wilson is visibly emotional.

“My heart is really, really big right now. I'm so happy,” she said, blinking back tears.

“All I can say is ‘Wow!’ … Wálas giáxsixa [thank you so much].”

An 11-year-old passes Wilson a box of tissues.

The class was months in the making, something Wilson had been planning since moving to the city to study at the University of British Columbia (UBC) last year.

But starting a new language program in an urban setting proved challenging. Lack of funding and classroom space were Wilson’s main obstacles, and the stop-gap solution — a crowded room in the Xwi7xwa Library at UBC's Longhouse — is not feasible long-term.

Indigenous languages in cities

The B.C. government's $50 million-language revitalization plan didn’t detail how urban language classes would be supported. Sixty per cent of Indigenous people in B.C. are urban, so only funding language classes on reserves excludes much of the population.

Simon Fraser University offers certificate-level Hailhzaqvla classes. However, they take place far up the B.C. coast, in Bella Bella, because the First Nations community has the highest concentration of Hailhzaqv citizens. The FPPC counted 106 speakers or semi-speakers and 247 learners there in 2014.

Local Vancouver-based classes mean that urban Hailhzaqv such as Wanda Christianson can finally learn her language.

She’s 64 years old, one of the keenest students in the class, and hopes learning her native language can help her path toward healing from the trauma of attending residential school.

”At residential school, I was only a number. This will give me an identity," said Christianson. "And I believe that learning the Hailhzaqv language is part of my culture and part of my identity… I would like to learn my language at this stage in my healing journey to gain my rights back that were denied."

Before the classes even began, she was excited about the idea of being in a room with fellow Hailhzaqv language learners.

Wilson figures there are 50 to 80 Hailhzaqv living in the Vancouver area and the 2016 census estimates there are fewer than 15 speakers in the city.

“I've been anxiously waiting for a language course,” said Chris Dixon, a class participant.

“It is hard because we have very limited fluent speakers down here we can talk to, face-to-face.”

From trainee to trailblazer

Despite over a decade of language learning, Wilson does not consider herself fluent in the Hailhzaqv language.

She first reconnected with her mother tongue in 2001, when she started working as a substitute teacher at Bella Bella Community School. That lead to a job with the school’s language department for 10 years.

She earned a language teaching proficiency certificate from SFU during that time, but provincial teaching regulations limited her to teaching only in Bella Bella. In 2017, she took the next step in her education journey and enrolled in UBC’s Indigenous Teacher Education Program.

It was an off-hand comment from her eight-year-old that made her want to teach Hailhzaqvla in Vancouver.

“Putting my son to sleep ... he said, ‘I wonder how many kids that live in this city even know our language?’” Wilson said.

She knew the answer was few, if any.

“I'm able to teach my children what I've learned at home. Why not teach people who are wanting to learn it that are living here in the city?”

But setting up classes in the city hasn’t been child's play.

Urban challenges

Little language support exists for urban Indigenous people. The B.C. government does not include language as part of its Off-Reserve Aboriginal Action Plan, and the federal government’s Aboriginal Languages Initiative funding is designed for institutions and organizations — not grassroots programs run by individuals.

However, Wilson said people wanting to learn Hailhzaqvla kept reaching out to her on Facebook, proving there was interest in urban classes.

She sent a survey to potential participants and received almost 30 responses. But enthusiasm alone was not enough to set up classes.

The first class was meant to be in February. Then, March. One week followed another without classes.

Wilson cited lack of space and funding as big challenges. With Hailhzaqvla learners spread across the Lower Mainland, a rent-free central location is difficult to find.

A team of UBC students, staff and faculty helped Wilson turn her idea into reality, from arranging a room in the library to creating teaching tools.

“I figured maybe after the second class we'll really figure out if the library is really the place to have it,” Wilson said.

She wanted funds to cover participants’ travel costs, but could not organize that before classes began.

Ideally, the classes will move to a more central location in the city. Christianson journeyed an hour to UBC on public transit, while Wilson’s commute is two hours.

For now, the class is volunteer-run but all the stresses have been worth it for Wilson.

“Our language is going to get stronger than it has, because you guys are here willing to learn,” Wilson said to her students at the end of her first class.

“And we're going to learn all of that together. I'm really happy it's finally here. It's happening."

As for Christianson, she hopes to eventually become a language instructor herself.

"I know that I can because I'm like a sponge when I learn … I delve right into it."

The More than Words series about B.C. Indigenous languages is produced in partnership with the Reporting in Indigenous Communities course at UBC's Graduate School of Journalism.

Listen to the More than Words special on CBC Radio Monday May 21 at 4 p.m. local time.