November 19, 2018

Warning: This story contains graphic descriptions of sexual assault that some readers may find disturbing.

This season, CBC podcast Someone Knows Something travels to Thompson, a northern Manitoba mining town, to explore a cold case more than three decades old.

- Listen to new episodes every Tuesday.

- Subscribe to the podcast at cbc.ca/sks or on iTunes.

It was the straight-forward voice of RCMP phone operator Marnie Schaefer that greeted a panicked, self-professed killer more than 30 years ago.

She was working the night shift in Thompson, a northern Manitoba mining city, when the phone rang around 2 a.m.

"He had said that he had just killed someone," Schaefer recalled. "Seemed to be terrified that I was recording the conversation that we were having."

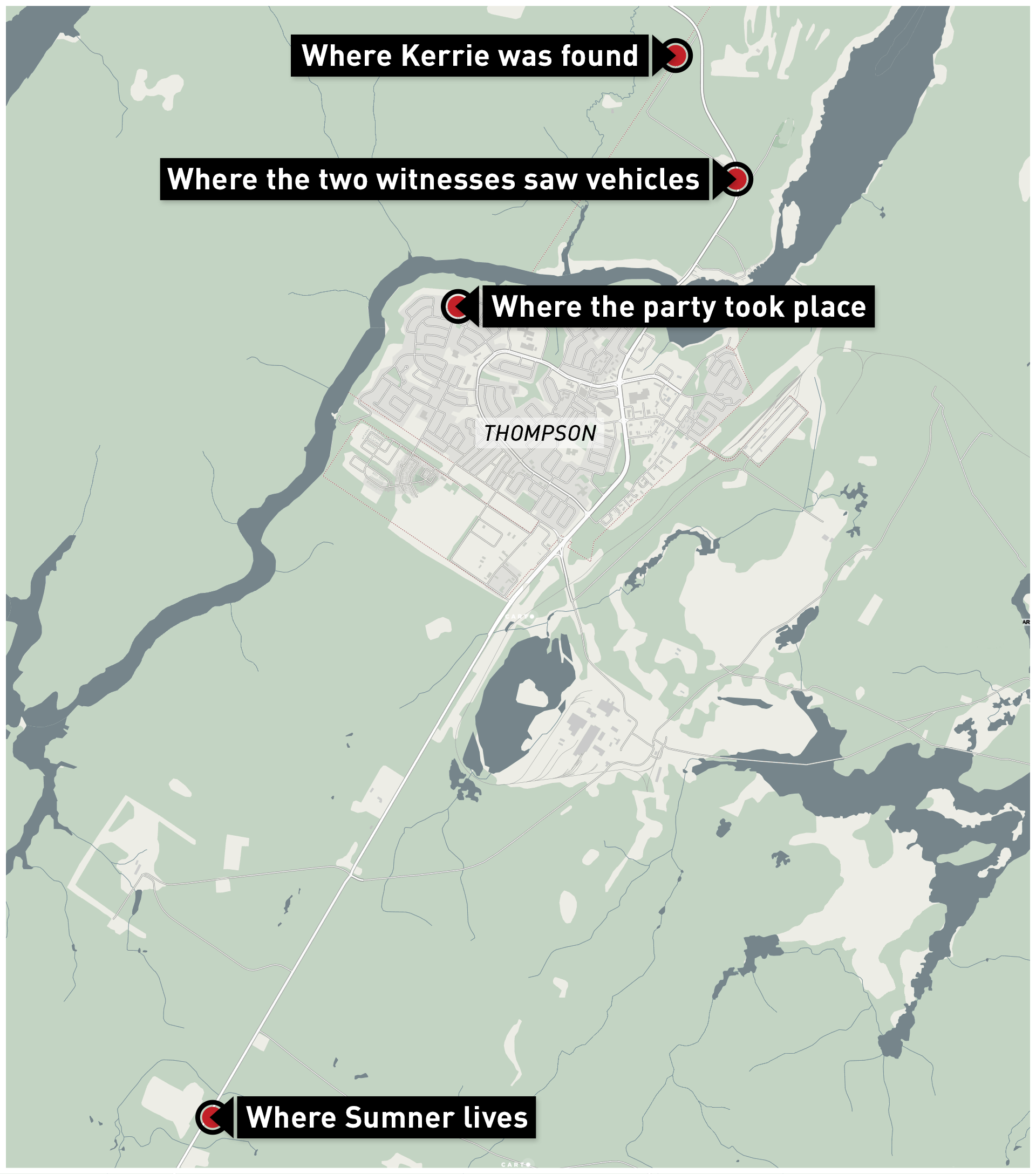

The call came two hours after Kerrie Ann Brown vanished from a house party on Thursday, Oct. 16, 1986 — and almost 14 hours before she was reported missing.

The 15-year-old later turned up dead.

And this mysterious call may not have been followed up on as part of the investigation.

Kerrie's unsolved death is the subject of the CBC podcast Someone Knows Something, which over the past 18 months has interviewed dozens, finding new information and witnesses.

It also explored for the first time accounts from Schaefer and the once-prime suspect in the case, Patrick Sumner. Both suggest investigators may have missed some crucial pieces of the puzzle, in part because they were too narrowly focused on Sumner.

Kerrie was reported missing at about 4 p.m. on that Friday. Her best friend told investigators Kerrie had disappeared from a party the previous night.

About 40 hours after that last known sighting, a pair of horseback riders came upon Kerrie's bludgeoned body in a wooded area near the outskirts of Thompson. Kerrie had been raped and was beaten to death with branches.

No one was ever convicted in her death, though police quickly zeroed in on 22-year-old Sumner as a suspect.

A witness, Sean Simmans, had told police he saw two vehicles leaving the area where Kerrie was found dead on the night of her disappearance: A 70s muscle car and a white van.

The description of the muscle car matched Sumner's car.

Arrest within a week

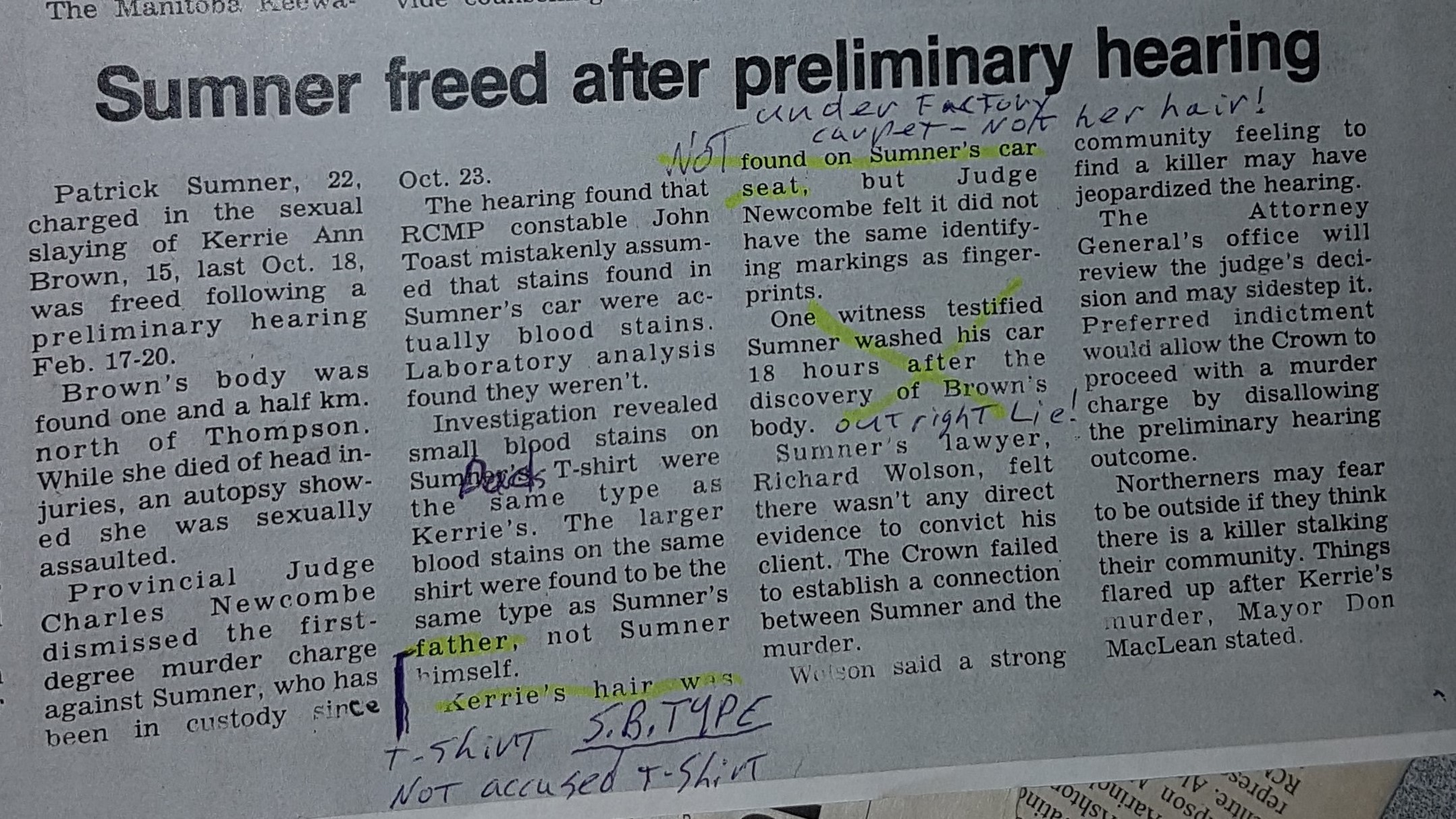

Investigators initially said they pulled hairs that were "consistent" with Kerrie's from Sumner's car. Multiple people present at his preliminary hearing told CBC the arrest was made because of a stain found in Sumner's car.

After further analysis, the hair couldn't be proven to be from Kerrie. The stain was a tomato-based juice spill that, according to Sumner, investigators used as a pretext to make an arrest.

More than one person claimed to see Sumner washing his car the day after Kerrie's disappearance.

The RCMP also seized a shirt from the Sumner household that contained blood matching Kerrie’s blood type, according to a news article about the case from 1987.

Sumner told the CBC the shirt — much larger in size than he wore at the time — belonged to his father and that the small blood stains were from pimples on his father's back. Forensic tests suggested it was his father's blood, Sumner said.

Sumner was arrested and charged with first-degree murder less than a week after Kerrie's death. But a judge stayed the charge during the preliminary hearing four months later because of a lack of evidence.

He maintains he "absolutely" did not have anything to do with the murder.

The effort to bring Kerrie's killer or killers to justice has snowballed into Manitoba RCMP's largest unsolved case, with evidence consisting of 14,000 documents detailing information from the 2,500 investigators, suspects, friends, loved ones and others who have been involved over the years.

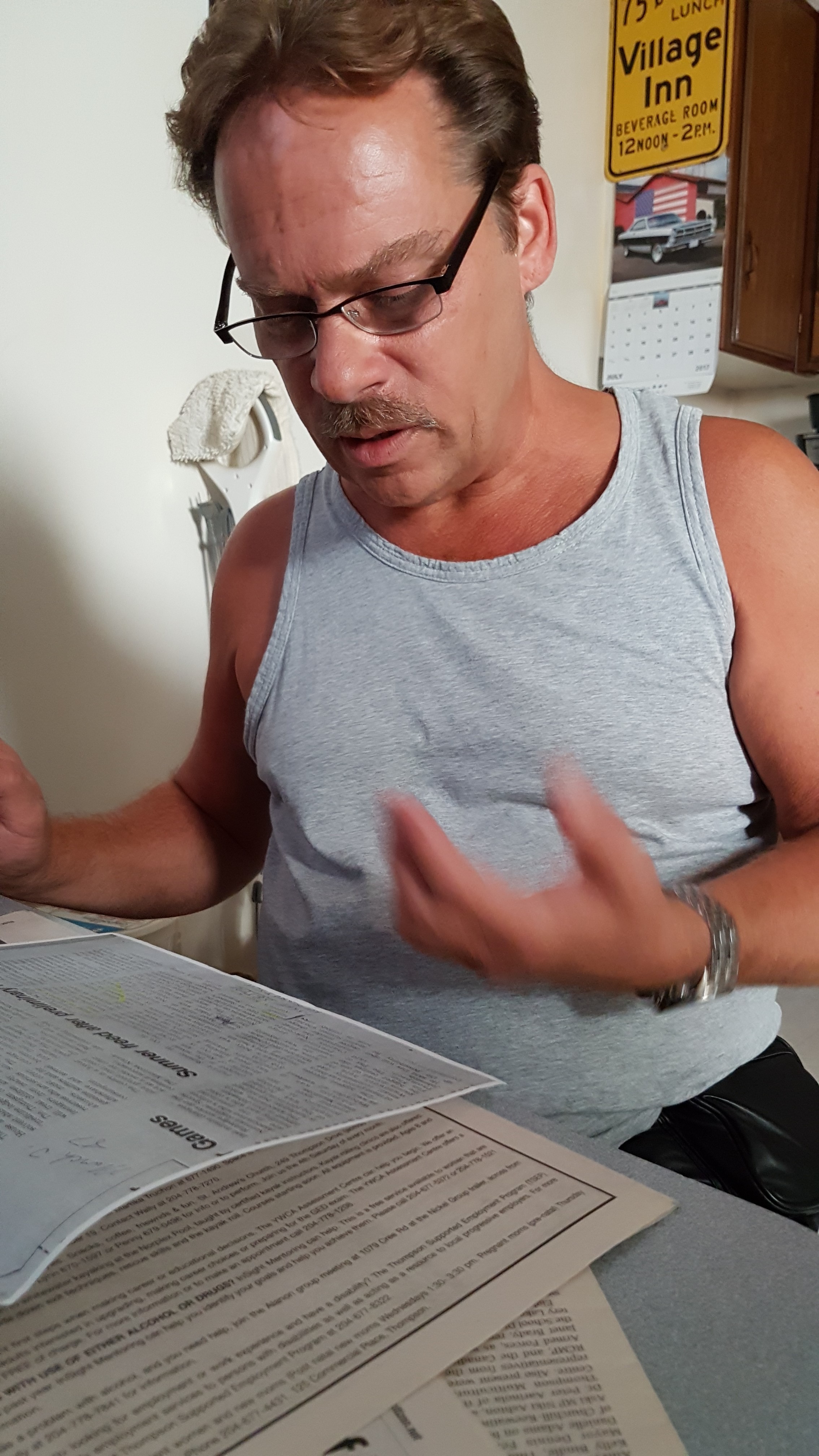

For Sumner, the time spent behind bars is still fresh in his mind: four months, 16 days and 23 hours.

Though he was freed more than 31 years ago, the reverberations of that initial arrest and charge have followed him ever since, turning him into a self-described "lost soul."

He still lives in Thompson, where he's struggled to find work in a community where some still think he's guilty.

"I got f--ked over," said a now-54-year-old Sumner.

Sumner says he lives with post-traumatic stress disorder that he attributes to the arrest and being shown the "horrifying pictures" of Kerrie's bludgeoned body during the preliminary hearing.

"Try being the guy they're accusing of those horrifying pictures," Sumner said. "You're not considered a victim."

Patrick Sumner gives his side of the story of why he was identified as the suspect in Kerrie Ann Brown's death in Episode 10 of Someone Knows Something.

The phone call

Today, the case remains open, which is one reason why Schaefer decided to speak out publicly about that cryptic confession she heard by phone 32 years ago.

Some of the case's key investigators dispute such a call was ever brought to their attention — another reason why Schaefer said she stepped forward to share her story.

It isn't clear who was on the other end of the line or whether it was connected to Kerrie's death. According to a CBC archives search, no other killings were recorded in Thompson and the surrounding area around that time.

"In my 20-plus years experience with the RCMP, not too many people will call up and tell you that they've just murdered someone if they haven't," Schaefer said.

The man never gave a name or any details about a victim, Schaefer said, but he had what Schaefer called a "northern" Indigenous accent. He also insisted he speak with a particular RCMP officer stationed at the Norway House Cree Nation detachment, an Indigenous community about 200 kilometres south of Thompson.

It sounded like the man somehow knew the officer, Schaefer said. She immediately played that officer the recording over the phone, she said, but the sound quality was poor and he wasn't able to identify the voice.

After Kerrie was found dead, Schaefer said she tagged the recording and alerted John Tost, who, along with Dennis Heald, was one of the lead investigators.

"He was not really interested in the tape," Schaefer said. “He said that he was pretty confident that they had the person that they were looking for.”

Both Tost and Heald told Someone Knows Something they weren't notified about such a call during the investigation.

"I don't recall ever being advised of it," Tost said. "But I can certainly tell you, if we had heard of anything along that line, we certainly would have [followed up]."

Schaefer recalls setting the tape aside, and said it appeared to sit untouched in the office for at least a month. Then it disappeared.

No known copies exist, but it was common back then for the RCMP call centre to reuse and tape over recordings every three months.

The investigation is now overseen by Const. Janna Amirault, who works with the RCMP's historical case unit in Winnipeg.

Over the years, Schaefer checked in with investigators a couple of times to see if her report about the call was ever looked into. She said she was always told it hadn't been, until recently, when she spoke with Amirault.

Amirault assured her that an RCMP officer in Thompson did visit the Norway House detachment and spoke with the officer named by the caller, but nothing came of it.

Amirault also confirmed to CBC she knew about the call, and said it "would have been followed up on."

Schaefer has never been officially interviewed by investigators.

Marnie Schaefer recalls the night she received a strange phone call from a man confessing to murder in Episode 9 of Someone Knows Something.

'Not found not guilty

Some former RCMP investigators haven't entirely ruled Sumner out as a suspect: They reiterate the judge discharging the hearing because of a lack of evidence is not the same as being acquitted.

"In other words, he was not found not guilty," Tost said.

Heald said he thinks there's "still something there," and Amirault also said she wouldn't exclude Sumner from the pool of possible persons of interest.

Sumner's friends and relatives say this air of suspicion has made life hard for the man they see as wrongly targeted.

Claire Henderson Dubé says she watched as her longtime friend was ostracized by much of the Thompson community, even after he was cleared of the charges.

Dubé was shocked when she learned of Kerrie's death — someone who was just two years younger than her.

She said she was with Sumner the night Kerrie disappeared. But there are a few discrepancies with Sumner's alibi.

According to police, Kerrie was killed some time between midnight and 1 a.m. on Oct. 17.

Sumner said he drove Dubé home around 8 or 8:30 p.m. and then went back to a local bar with two other friends, Lindsay Lang and Curtis Didluck. He was home with his mother by 10 p.m., he said.

Dubé recalls that the pair went out for drinks and she wasn't dropped off until sometime between 11 p.m. and 12:30 a.m.

'He's one of the most gentle people that I know. You'd have to be whack to be able to do what somebody did to that poor girl. It's just not fair.' — Claire Henderson Dubé

In a brief phone interview with CBC, Lang said he and Sumner were together during the day — but "not really at night." Didluck passed away in 2016.

Sumner's mother, Rosalie, recalls him coming home late from work that night, though she can't remember the exact time. She saw her son making a sandwich before bed.

"It's been very hard," said Rosalie Sumner. "He can't get a job in town, for one thing, at all. There are still people who think he's guilty."

Not long after the police first arrested Sumner in 1986, they visited Dubé, offering up what she called a "total bullshit" theory.

The RCMP suggested Sumner had an "ongoing crush" on Dubé but feared rejection, she recalled. Those frustrations boiled over, motivating him to instead rape and kill Kerrie, who was similar in age and appearance to Dubé.

Sumner was a stable person "who couldn't hurt a dog," Dubé said, let alone rape and murder a 15-year-old girl.

"He's one of the most gentle people that I know. You'd have to be whack to be able to do what somebody did to that poor girl. It's just not fair."

The last interview Dubé did with police was in the mid-90s, when she said they asked her again about why her timeline of events that night didn't match Sumner's.

The officer conducting the interview also invited her to look at Sumner's statement and handed her a file, she said. Upon opening it, what she saw instead were brutal pictures of the crime scene.

"I lost my temper," she said. "I told them I didn't give a f--k if it was my father that had done it, if I had known who'd done it, I would f--king say so because they should be punished, plain and simple."

Trevor Brown confronts Patrick Sumner, the prime suspect in Brown's sister's death, in Part 2 of Episode 10 of Someone Knows Something.

'I was it'

That Sumner washed his car in the days after Kerrie's death was also framed as suspicious during his 1987 preliminary hearing.

Tire tracks were found in the mud at the crime scene, along with an air mattress, a rubber car mat and other items that may have been used as traction by a stuck vehicle.

Local body shop owner Roland (Rolly) Becker was one of the witnesses who said he saw Sumner washing his car outside his family home on the day Kerrie was reported missing. It took him an inordinate amount of time, Becker said.

Sumner doesn't deny washing his car but says he did it on that Saturday. On Friday, he said, he would've been in mechanics school until about 4 p.m.

"If I was trying to hide something, I wouldn't be in [a high-traffic area], washing my car," he said, referring to the city dump, which the Sumner family operated and lived next to.

"Think: It's a public facility."

Sumner also said he voluntarily took a lie-detector test and gave police a sample of his hair. He assumed the latter was for DNA testing.

It wasn't until the 1990s that DNA became a centrepiece of criminal investigations and the RCMP began collecting samples in earnest in the Kerrie Brown homicide.

Sumner also criticizes the way Tost first interrogated him.

He said Tost told him, "You might as well confess, because your life's over anyway."

"That's before he ever seen me before in his life, never talked to me yet ... and he decided in that point in time I was it," Sumner said.

At the end of the interview, Sumner said he told Tost and Heald they had the wrong guy. He said he had not requested a lawyer be present because he "had nothing to hide."

Sumner also maintains Sean Simmans made "false statements" to police about seeing him and his car on the night of Kerrie's disappearance.

Simmans, along with his friend Larry Leepart, testified about the two vehicles they saw emerging from the only road that led to the crime scene where the body was later found.

According to those present during the preliminary hearing, Leepart was in the passenger seat and never got a good look at the driver of the muscle car. Leepart declined an interview request.

Simmans, however, told CBC he remains 90 per cent sure it was Sumner he saw behind the wheel that night.

"If you believe something in your mind, you're going to believe it, I guess," Sumner said of Simmans's claim.

He feels similarly about the police investigation that ultimately saw him charged so many years ago.

"I did all I could do," he said. "I co-operated so they could eliminate me as a suspect, but that's not what they did."