January 20, 2019

As a grey and ashen Soleiman Faqiri lay flat-lining on the floor of a cold, unfamiliar jail cell, guards scrambled to shut the shutters of the cells nearby.

It was too late.

Across the hall, one inmate had already seen what he says was the most disturbing thing he’d ever witnessed inside a jail, something seared into his mind to this very day.

“I kept thinking to myself, ‘When is this going to end? What's the end game here?' ” said John Thibeault.

On Dec. 15, 2016, Thibeault was standing at the window of cell B-11 at the Central East Correctional Centre in Lindsay, Ont., pacing restlessly as he waited for his methadone treatment which was by now about an hour late. It was almost 3 p.m. and he was becoming impatient.

- Watch The Fifth Estate's: The jail death of Soleiman Faqiri

Suddenly, six guards came into view holding an inmate he hadn’t seen before. Thibeault didn’t know his name, but it became one he’d never forget.

As they made their way toward cell B-10 at the end of the hall, Thibeault noticed one of the guards lean in and whisper into the inmate’s ear. The inmate whose name he’d soon learn was Soleiman Faqiri began to hesitate, not wanting to go in.

That’s when Thibeault says things spun out of control.

For the next 10 minutes or so, he stood transfixed as guards delivered what he described as a violent torrent of kicks, punches and blows against the 30-year-old mentally ill man in what would be the final moments of his life.

“I've never seen nothing like it. And I've seen a lot of messed up stuff in jail,” Thibeault, 32, told The Fifth Estate, breaking his silence for the first time since Faqiri’s death.

“Was I scared? Absolutely,” he said. “These guys are still beating on him while he's not even moving? And he's in restraints and he's on the ground? And he's been pepper-sprayed twice? ‘Course I was scared. I'm like, if these guys get away with it with him, they can get away with it with anybody.”

More than six months later, a post-mortem report deemed the cause of Faqiri’s death “unascertained,” with the Kawartha Lakes Police Service concluding there were no grounds for criminal charges against any of those involved.

But amid a nearly year-long investigation by The Fifth Estate, Ontario’s chief coroner Dr. Dirk Huyer has reopened the probe into Faqiri’s death after new evidence came to light that “required further investigation within a criminal justice perspective.”

Huyer wouldn’t say what that new evidence is, but he did confirm the investigation is being handled by Ontario Provincial Police.

The Fifth Estate obtained more than 1,500 pages of never-before-seen documents, including police notes, witness statements, hundreds of photos and the names of correctional officers involved that shed new light on what happened to the 30-year-old the day he died.

As part of its investigation, The Fifth Estate also sought out an expert review of the case, which revealed Faqiri’s death may have been directly caused by guards piling on top of him in those last minutes while his hands and feet were restrained.

It was eight hours before Thibeault learned that the man who lay motionless as guards yelled “Stop resisting” was in fact dead.

Still waiting for his methadone, he asked a guard how much longer it would be. The answer: He’d have to keep waiting. There was a body in the cell across the hall that needed transporting.

That night, investigators asked to speak with Thibeault.

Down the hall, two police officers sat in an interview room set up with an audio recorder. Outside stood a corrections officer, according to Thibeault, staring intently at him.

"If I could read his mind and his eyes, they would have said, 'Keep your mouth shut,’ " Thibeault said.

He did, terrified of what might happen if he spoke out. Until now.

II.

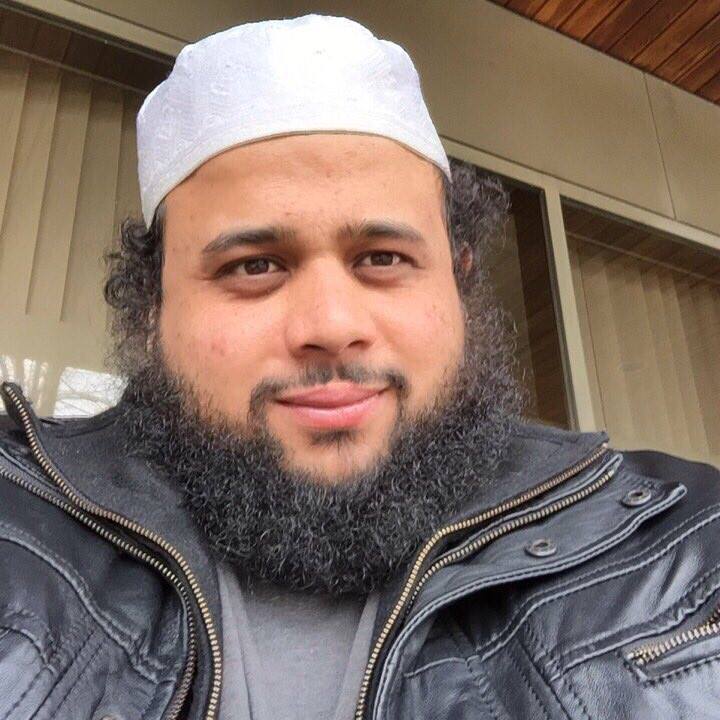

Faqiri was born on a cold New Year’s Day in 1986 in Afghanistan.

One of five children — four brothers and one sister — he was just eight when his parents, Ghulam and Maryam, brought the family to Canada. They soon settled in Pickering, Ont., just east of Toronto.

A straight-A student in high school, according to his family, Faqiri spoke three languages — English, Persian and Arabic — the latter of which he taught himself. At one point, he was captain of the Pine Ridge Secondary School rugby team and spoke half-jokingly of becoming a professional athlete.

By the time Faqiri graduated, his future looked bright. In 2005, he enrolled at the University of Waterloo, where he studied environmental engineering.

But his plans were cut short. That year, his life took a drastic turn when he was diagnosed with schizophrenia following a car accident that made it impossible for him to continue with university.

In 2012, there was a brush with the law. That September, Faqiri was arrested after stealing a quantity of clothing. He was convicted in April 2014 for theft under $5,000 and ordered to pay restitution of $980.

His troubles didn’t end there.

Over the years, Faqiri struggled, sometimes going three or four days without sleeping, never able to work a full-time job, according to his family. Police records show he was arrested on 10 occasions by the Durham Regional Police Service under Ontario’s Mental Health Act and had a “history of non-compliance with his prescribed medications.”

All the while, his family says, Faqiri’s interest in learning continued, turning from engineering to religion. He spent countless hours studying the Qur’an in hopes of one day becoming an imam.

Some days were worse than others. In March 2016, Faqiri stopped taking his medication. The next several months would be a struggle for him and his family. On at least one instance in the days leading up to his arrest, Faqiri appeared particularly agitated.

Video footage posted on Instagram on Dec. 5, 2016, and obtained by The Fifth Estate provides a glimpse into Faqiri’s condition.

In the video, Faqiri appears visibly worked up, behaving strangely. Dressed in grey traditional garb, he approaches a man in a weight room at the GoodLife Fitness centre in Ajax, Ont., where he was something of a regular. He says a few words to the man, who doesn’t appear to respond.

In a video posted to social media a few days before he died, Faqiri appeared to be behaving strangely at a Goodlife Fitness centre in Ajax, Ont. (zack_king_khan/Instagram)

Faqiri begins kicking at a piece of heavy equipment as the man gets up and walks away. All the while, Faqiri’s focus seems squarely on the equipment. He lifts it off the ground and slams it back down before tossing what looks like a rosary into the air, catching it again and walking off.

On Dec. 4, 2016, Faqiri was arrested in Ajax on charges of assault, aggravated assault and uttering threats. According to a police report, a dispute erupted between Faqiri and his neighbour. When the neighbour’s daughter intervened, Faqiri allegedly stabbed her in the stomach with an “edged weapon.”

He spent that night in custody at a Durham Regional Police station.

A spokesperson for the force refused to speak with The Fifth Estate about the circumstances of Faqiri’s arrest or Durham police’s handling of incidents in which a person has mental health issues.

The following day, Faqiri appeared in court by video before being remanded into custody at the Central East Correctional Centre, better known as the Lindsay jail, 130 kilometres northeast of Toronto.

On Dec. 6, Faqiri was moved into segregation. A police report attributes the move to concerns for his safety and that of other inmates and jail staff.

In Ontario Court of Justice in Durham, a judge expressed concerns that Faqiri’s mental health was impeding his ability to understand the proceedings and ordered him back into custody in the hopes that three days of medication might help make the next court date go more smoothly.

On Dec. 9, Faqiri was to attend court again by video. Instead, he’d smeared feces on himself and guards weren’t able to take him to the screening area.

By Dec. 12, prosecutors made contact with Faqiri’s family. His brother Yusuf, two years his senior, told the judge in court that day that Faqiri, whom he observed by video link, seemed worse off than he could remember. The judge ordered that Faqiri undergo a mental health assessment to determine if he was fit to stand trial.

Faqiri was to return to court Dec. 19. He never made it.

III.

A report by Kawartha Lakes police paints a painful picture of Faqiri’s condition in segregation. Within the first few days, he’d covered himself in urine, was drinking water from the toilet bowl despite having access to drinking water and was throwing himself against hard surfaces.

By all accounts, Faqiri was deteriorating.

Anthony Ouellette remembers his time in the cell beside Faqiri vividly. In a visiting room at the Ontario jail where he was transferred after Faqiri’s death, Ouellette spoke publicly for the first time about his memories of the inmate in the cell next to his own.

When Faqiri arrived on the range, it was impossible not to notice. That first night, he kept the entire unit up banging on the cell walls and chanting, Ouellette said.

With a long list of robberies to his name, Ouellette was part way through a seven-year term when the two crossed paths. The first time they met, Faqiri appeared panicked, walking around his cell naked with water all over the floor.

“Are you OK?” Ouellette recalled asking. “Do you need help?”

Faqiri replied: “Help, help,” Ouellette said.

“Repeating it, you know? And whenever a correction officer would come near him, he’d freak right out…. He didn’t eat. He wouldn’t come near his door when the guards tried to feed him.

“I'll never forget when I looked in his eyes and I just saw such a sad, sad person, a person that just was screaming out for help,” said Ouellette. “This was an individual that not only suffered from mental illness [but] I believe shouldn't have been in jail in the first place.”

Over those few days, said Ouellette, Faqiri was “out of control.”

“Not threatening people — just yelling in his own language, pacing back and forth, banging on the walls … like the cell was a jungle gym, you know? We just all felt horrible for him.”

Faqiri was especially upset when female guards approached his cell, Ouellette said.

“I heard them laughing, basically making fun of his genitals,” Ouellette said. “Whenever they went to his cell, he would cover himself and be shy.”

On one occasion, Ouellette heard Faqiri say a few words in Arabic and guessed he might be Muslim. To find out, he held up his copy of the Qur'an to see how Faqiri would react. His demeanour, said Ouellette, instantly changed. “He was happy.” Another time, he said, the two prayed together at Faqiri’s door.

It just gave us all the chills.

Ouellette said he tried many times to advocate for Faqiri. On Dec. 14, he tried twice.

“The doctors and nurses came to his cell to talk to him. I called them to my window.”

Faqiri hadn’t been eating, Ouellette told them, and needed help.

“He’s not OK…. He needs to be going to a hospital, you know?’”

“I’ll be the judge of that,” he said the doctor replied, the medical team persuading him to let them administer a needle.

“It didn’t do nothing,” Ouellette said. To him, Faqiri remained as agitated as ever.

The Fifth Estate contacted the doctor who treated Faqiri at the jail, but the request for comment was declined.

Later that day, Ouellette repeated his concerns to a sergeant who had come on shift. “The sergeant got pretty angry, not at me, but he stormed out and came back with staff.”

Over the next hour, they managed to persuade Faqiri to have a shower. “Do you trust me?” the sergeant asked, eventually handcuffing him and taking him to the showers.

“The sergeant was a very kind man,” Ouellette said. “He himself got in the shower with him and helped him put soap on and helped him push the button to clean himself.” It was perhaps one of the few bright spots in Faqiri’s time in custody.

That night, Ouellette said, barely any of the inmates could sleep. Faqiri was up at all hours, his voice echoing off the walls as he chanted the Canadian national anthem again and again.

“Over and over and over. That’s what we all remember: that he was screaming O Canada.

“It just gave us all the chills.”

The next morning would be Faqiri’s last. On Dec. 15, Faqiri was transferred to the jail’s maximum segregation unit.

![Instead of a hospital, Faqiri was transferred to a cell at the back of the jail’s maximum segregation unit, known as 8-seg, where he would be dead within hours. (Kawartha Lakes Police Service) ]](https://newsinteractives.cbc.ca/craft-assets/images/BEST-FOR-ONLINE-02.-Pages-from-ATIP-DOCUMENT-FROM-LAWYERS_decrypted-159-320_Page_050_Image_0001.jpg)

Jail staff “felt that Soleiman could be better supervised and supported” there, a police report said.

That morning, medical staff arrived to administer another needle. Ouellette said he tried again to get Faqiri help and several correctional staff also tried to persuade the doctor to have Faqiri transferred to a hospital to be cared for. But according to Ouellette, the doctor refused.

“I heard it directly out of his mouth: ‘He doesn’t meet the criteria to be sanctioned to a hospital,’” Ouellette said. “That was the end of that.”

Faqiri was rolled away from his cell in a wheelchair, wearing nothing more than boxer shorts and covered with blankets. Ouellette never saw him again.

IV.

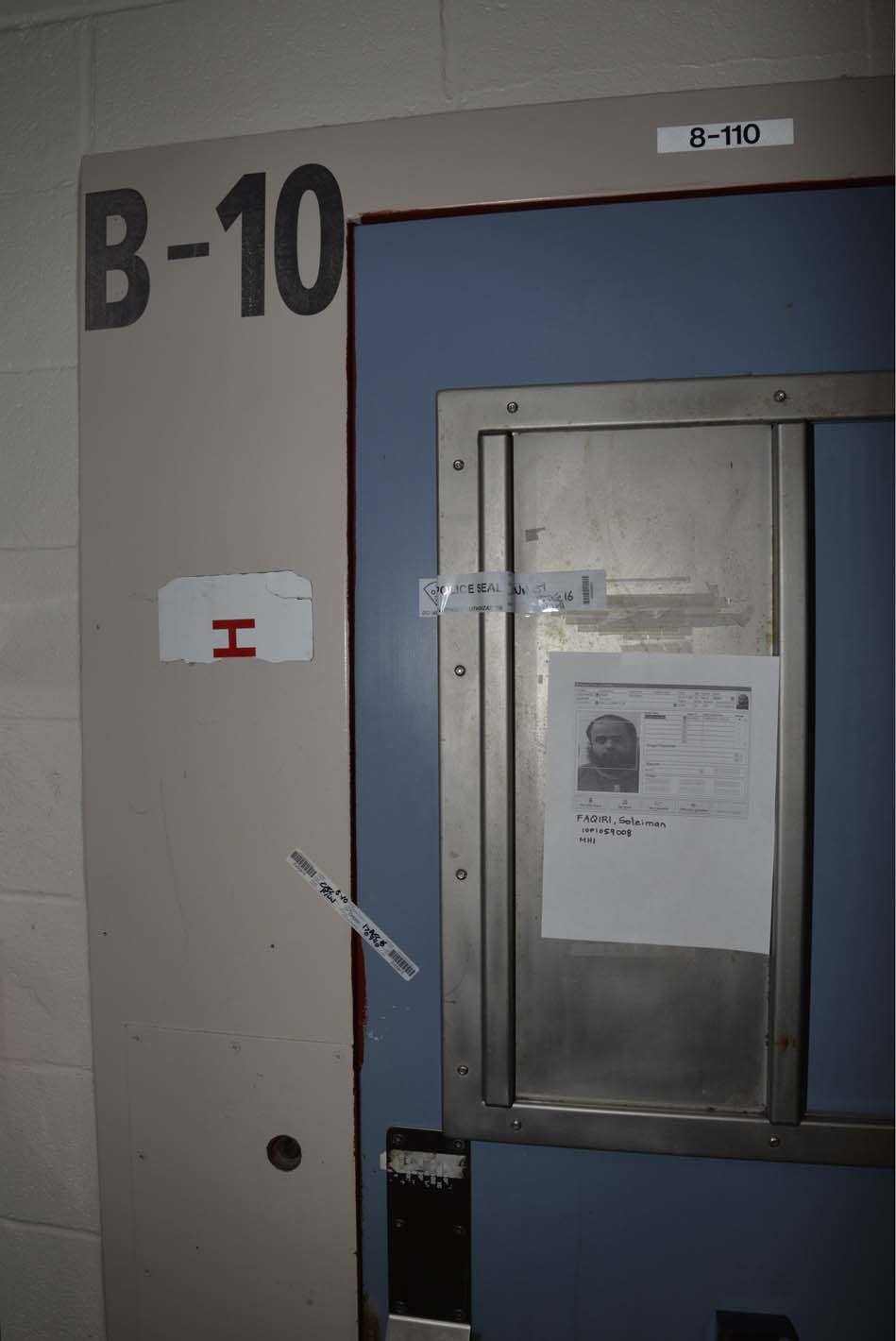

Along a dimly lit hallway enclosed by white concrete walls is a series of doors, some a clinical pale blue, others an anemic pink, giving a hospital-like feel to the Central East Correctional Centre’s maximum solitary confinement unit, known to inmates and guards alike as 8-seg.

On one end of the hall is a pair of pink doors, each marked “shower.” In front, there is what looks to be a nurses’ station plastered with a collage-like collection of signs.

“Caution.” “No razor, no pencils.” “Suicide watch.” “No juice bags.”

Scotch-taped to each pale blue cell door is a sheet of paper with a black-and-white photo of the inmate inside. At the farthest end of the hallway from the showers is cell B-10, where Faqiri was supposed to be housed until his mental health assessment. That was the plan, anyway.

A police report outlines the official version of what happened instead:

Around 1:15 p.m. on Dec. 15, Faqiri was escorted in a wheelchair to the shower. He stayed there for about an hour and a half, refusing to come out, spraying water and shampoo through the barred stall door.

Fifteen minutes later, the supervising officer called the unit’s deputy superintendent requesting the help of the crisis intervention team, known as ICIT. Meanwhile, guards placed a welding shield outside the shower to protect themselves from the water. The request for a crisis team was denied.

Instead, a psychologist employed by the jail arrived, offered Faqiri crackers and peanut butter if he would co-operate and go to his cell. That seemed to calm Faqiri down.

By 2:50 p.m., Faqiri agreed to be handcuffed. Five correctional officers began to escort him down the hall. A sixth joined and Faqiri’s behaviour escalated, according to the report.

Faqiri began resisting entry into his cell, spitting at the guards. One officer delivered “an open hand strike” but missed, according to the report. Faqiri was pepper-sprayed and forced into the cell, where there were no cameras.

What happened next isn’t captured on video. Instead, the rest of the report relies on “interviews of the involved parties, witnesses and forensic evidence.”

Inside the cell, Faqiri reportedly continued to resist the efforts of guards, whose goal, according to the report, was to remove his handcuffs and leave. As they tried to keep him on the ground, Faqiri, with his wrists cuffed, apparently tried to strike at the guards and get on his feet. A second round of pepper spray was used. Faqiri was on the ground again, with his head toward the cell door.

“Code blue” was called — an emergency call to any available guards to assist. Twenty to 30 guards arrived and the original guards “tap out,” “exhausting themselves” in the struggle.

As CBC News revealed in the days after his death, Faqiri’s limbs were held down as leg irons were put on and a spit hood was placed over his head. The officers were able to gain control of Faqiri, who, according to the report, was “exhibiting assaultive and resistive behaviour.”

Faqiri appeared to become “compliant,” the report says. He was turned, his head now at the back of the cell away from the door, face down, arms above his head, and reportedly responded when told his cuffs would be removed.

He placed his hands behind his back and was handcuffed. The remaining guards left the cell. The door was locked.

According to the report, a supervisor mistakenly believed the ICIT team was on the way to remove the cuffs from Faqiri and put him in a recovery position. It wasn’t.

Instead, moments later, one of the staff noticed through the window that Faqiri wasn’t breathing. The cell door was opened and guards attempted CPR. 911 was called. Nurses attempted resuscitation with a defibrillator. Paramedics arrived. Life-saving efforts failed.

At 3:47 p.m., Faqiri was pronounced dead.

That night, his family received a knock at the door from two Durham Region police officers telling them the unthinkable: their son was never coming home.

For the next year and a half, Faqiri’s family waited in agony, trying to make sense of what happened to their son and brother.

"We want to know why my brother died," Yusuf Faqiri told CBC News in the days after his brother’s death. "Why did Soleiman die? How did Soleiman die? That's what we're looking for."

Closure, they thought, might come in the form of a coroner’s report. Instead, on July 11, 2017, the long-awaited report deemed Faqiri’s cause of death “unascertained.”

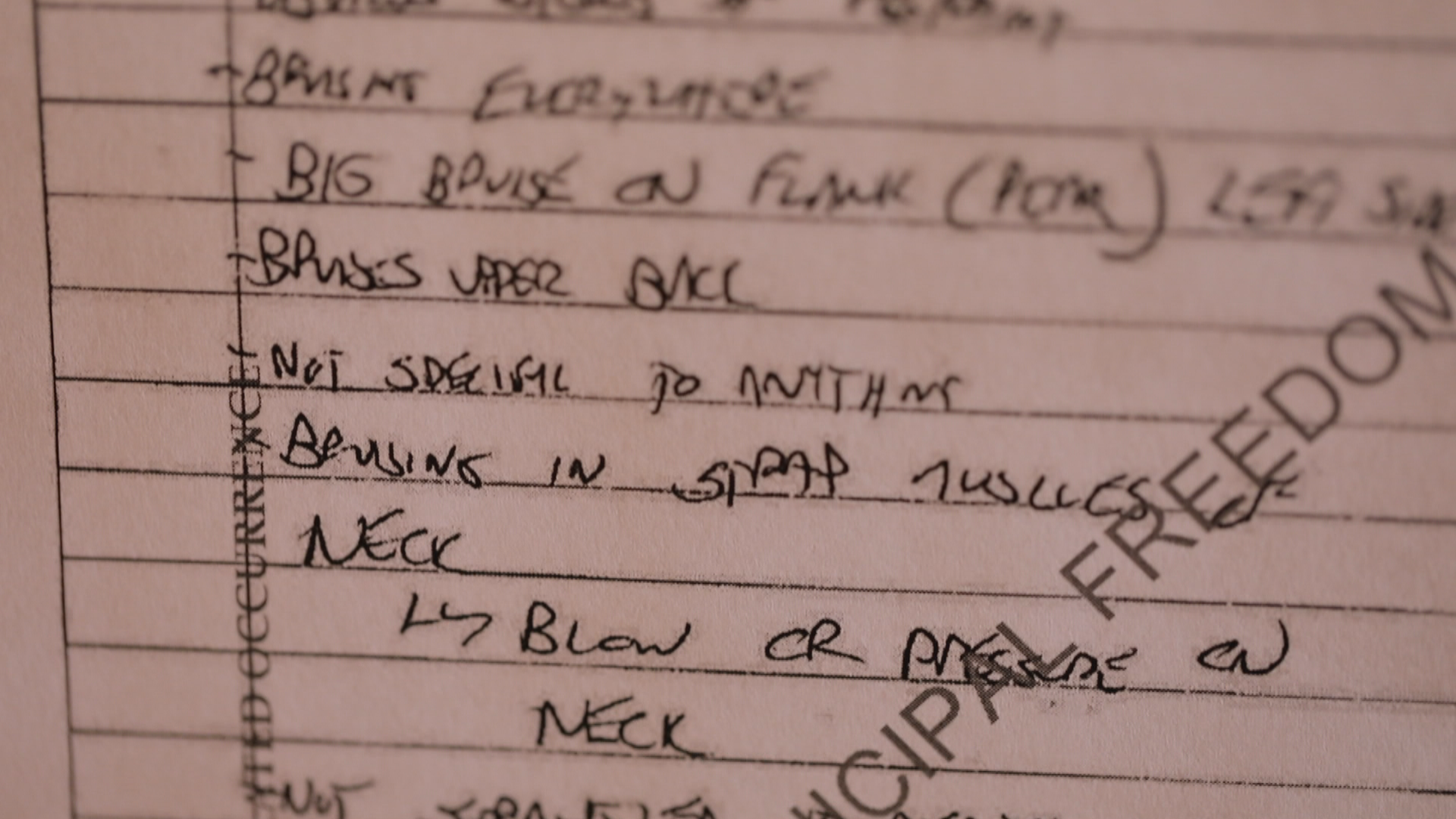

The report listed a litany of injuries that the 30-year-old suffered in the final moments of his life, with more than 50 signs of “blunt impact trauma,” including abrasions across his body, ligature marks around his wrists and ankles, bruises to his upper and lower extremities — and to his neck.

"Many of the injuries would be in keeping with the story of attempts to restrain this man, but falls, or blows or other impacts to these regions cannot be excluded," the report said. Still, none were deemed sufficient to have killed Faqiri. Among the causes ruled out were disease and genetic mutations of the heart and blood vessels.

What could not be ruled out, according to forensic pathologist Dr. Maggie Bellis, was asphyxiation, which might or might not have resulted from the spit hood.

Her conclusion: It was impossible to pinpoint a cause of death. Investigators with the Kawartha Lakes Police Service concluded there were no grounds for criminal charges against any of the correctional staff involved.

But for all the detail contained in the report’s 56 pages, the family was left with many more questions about Faqiri’s death.

As it turns out, they weren’t the only ones with questions about just what happened that day.

On Dec. 15, 2016, paramedic Jason Bibeau had been driving down Kawartha Lakes County Road 36 on a routine EMS call when a call came from dispatch asking if the patient he was transporting was stable enough for him to make an emergency stop at the Lindsay jail. It was for Faqiri.

A paramedic with 27 years of experience, Bibeau provided a witness statement to police in the days after Faqiri died, of which The Fifth Estate obtained a video recording.

Bibeau’s patient was stable, so he agreed to make the stop, arriving at the jail at 3:20 p.m. Inside, he was led to the top floor, where Faqiri was lying with no vital signs.

“It was kind of chaotic to be honest,” he said. “I needed to know what happened, what exactly happened here ... anybody witness it? I had about five people start to tell me at once and I couldn't — I’m like, ‘Just stop, I need one person to tell me.’”

Immediately, Bibeau started an intravenous line. Around that time, documents show, a second wave of paramedics arrived, a guard telling them: “He should be calm for you now, he was very violent.”

“I was confused,” one of the paramedics said in his statement, “because we were called for a dead guy.”

Even with emergency drugs, Faqiri’s heart wasn’t responding. A few minutes later, Bibeau phoned the physician at the local hospital, explaining what happened as best as he could.

Faqiri had been without a pulse for at least an hour. At 3:47 p.m., resuscitation efforts ceased.

In the ensuing minutes, Bibeau said he was given conflicting accounts about what had happened. Up to that point, he was told Faqiri had been in the cell alone when a guard noticed he’d stopped breathing. Later as he was packing up, another guard “piped up and said, ‘Wait a minute, no, he was never left alone.’ ”

If that were true, there would have been a guard in the cell with Faqiri when he stopped breathing, Bibeau recalled thinking. He started asking more questions. “The superintendent started getting antsy … almost having attitude with me a little because I was asking all these questions.

“I stopped dead in my tracks and I go, ‘I don’t really care who you are at this point, I’m the advanced paramedic. I just got a pronouncement for a 30-year-old man.’ I needed a straight story, I needed to know what was going on.”

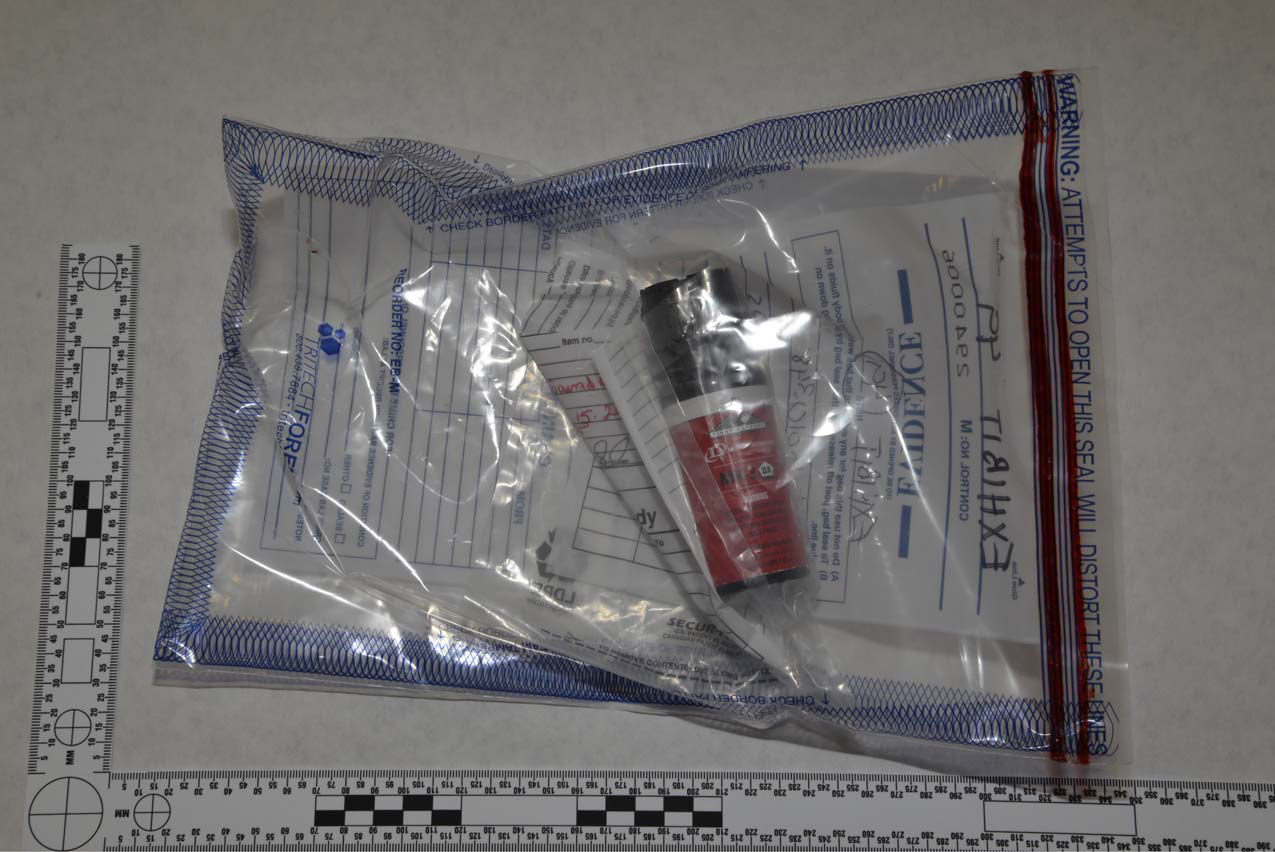

Adding to the confusion was the fact that there were three unknown pills on the cell floor, he said, with no explanation of whose they were or how or why they were there.

“Seeing these pills and hearing that he wasn't by himself, that’s what made me uneasy,” Bibeau said.

“I don't know if the left hand knew what the right hand was saying or doing,” he said. “But the story I got for 9/10ths of the time that I was on scene was that he was in there by himself and was calling out for a nurse.”

With his statement complete, Bibeau had a moment alone, wiping his eyes. He let out a breath before the interviewing officer returned. The camera was shut off.

V.

For months now, John Thibeault has been free. But his conscience hasn’t been.

Looking out of a car window on a grey and rainy autumn day, flashes of what he describes as the “non-stop violence” leading up to Faqiri’s death play through his mind as they have every day since. “There’s a piece of me missing. My loved ones have told me that.”

“Call me a snitch, call it whatever you want. So be it,” he said. “The last thing I want is my face on the news, on TV. But what happened that day is not right.”

For nearly two years, Thibeault kept silent — fearful not only of the repercussions of speaking out while he was still behind bars but also that he might not be believed.

“I knew in my head that if I ever wanted justice for him and the family that I would need to keep silent until the right time — until I wasn’t incarcerated. Because pretty much anybody that’s incarcerated, no one’s really going to believe.... Everyone’s looking for a get-out-of-jail-free card. It means more that I’m out here doing on my this own.”

It took a long time to make up his mind, Thibeault said.

“But all I know is that if it was me, I’d want my family to have those answers. I’d want them to have closure on how their son died.”

Around 3 p.m. on Dec. 15, 2016, Thibeault, standing at the window of his cell B-11, watched as six guards came into view with Faqiri.

“I heard him ask, ‘I haven’t eaten yet. Am I going to?’ ”

“Your food’s already in the cell,” one of the guards shouted. According to Thibeault, one of the guards then whispered into Faqiri’s ear and that’s when he began resisting. “He wasn’t aggressive or anything, he just didn’t want to go in. I don’t know if it was what the guard said into his ear that agitated him, but he did not want to go into that cell.”

Immediately, said Thibeault, one of the guards brought out a canister of pepper spray, spraying Faqiri in the face. Much of it, he said, went into Faqiri’s mouth.

“Usually, when an inmate is being moved or acting out, guards come around and close the shutters,” he said. “That day, I guess because they didn’t know what was going to happen … my shutter was open.”

Inside the cell, Thibeault said, the “beating” began.

For the next several minutes, Thibeault stood frozen, peering out of the window of his cell door, hoping he wouldn’t be noticed.

“Blood flying, limbs — it was brutal,” he said.

Four guards — weighing at least 250 pounds each by his estimate — started punching Faqiri in the face as the supervisor threw the mattress, food trays and everything else out of the cell, he said.

“They were kicking his head up off the ground…. When he tried to get up onto his knees they hit his head off the corner of the bunk,” he said. A smaller guard, he said, was “calling the shots.”

As the blows continued, Thibeault said Faqiri managed to get to his feet, despite the guards trying to hold him down “punching him, kicking him … just whatever shots they could get in.”

Over the span of at least 10 minutes, he said, Faqiri got up three times. “It must have been the adrenaline when you’re fighting for your life…. Every time he got up, the only place he had to run was the back of his cell. I seen him run into the wall two or three times.”

All the while, according to Thibeault, Faqiri didn’t deliver any blows of his own. “You can’t throw punches or fight the guards when you’re handcuffed.”

When the guards got Faqiri to the ground for the second time, Thibeault was still peering out and saw a female guard standing on the bed, out of the way of the commotion. “Do you want me to call it?” she asked.

She was referring to “code blue,” the emergency call that would have immediately brought any available guards to come and assist. Thibeault didn’t hear a response but said the call wasn’t made right away.

Several more minutes passed before “code blue” was called, Thibeault said. But before that happened, Faqiri was pepper-sprayed again. By this point, inmates in the cells nearby started reacting to the commotion, yelling and kicking at their doors. After a second attempt to get on his feet, guards got Faqiri down to the ground a third time. This time, he wasn’t moving.

That’s when, Thibeault said, he noticed the smaller of the guards had his knee into Faqiri’s neck. As the surrounding inmates starting yelling, the guard started to yell as well: “Stop resisting, stop resisting.”

But Faqiri wasn’t resisting — he wasn’t even moving, Thibeault said. “And I’m figuring, ‘Why is he saying that if he’s not moving?’ ”

Still yelling at a motionless Faqiri, Thibeault said the guard looked up and noticed him at his window. They made eye contact, he said, before the guard immediately jumped up and closed Thibeault’s shutter — something that in his mind only reinforces that Faqiri hadn’t been resisting.

“You’re going to hop up off him, run out of the cell … and shut my shutter? But you’ve got a 250-pound inmate in this cell that’s resisting?”

After that, Thibeault could no longer see what was unfolding. But the sounds still haunt him.

“Code blue, 8-seg,” he heard over the intercom.

Footsteps down the hall.

“Medical emergency.”

More footsteps.

Shaken, Thibeault crawled into his bed, pulling the covers over his head. The methadone he’d been anxiously waiting for was now the furthest thing from his mind. “I don’t even know what I just witnessed,” he thought to himself, not knowing whether the inmate across from him was alive or dead. Surely he’d be taken to a hospital, fixed up and brought back, he thought.

At 11 p.m. that night, Thibeault learned that the events he witnessed that day were in fact the final moments of Faqiri’s life. “Mind you at the time, I didn’t even know his name.”

For four days after his death, Faqiri’s picture remained taped to the door of his cell. For four days, Thibeault relived those 13 minutes each time he went to the door for his meal tray.

“That’s how I actually learned his name…. Until finally I lost my mind a bit and told the guards, ‘Can you please take that picture down?’ ”

Beginning the day of Faqiri’s death, Kawartha Lakes police started collecting the use-of-force reports that guards are required to fill out any time force is used on an inmate.

In the days that followed, they created a list of who was involved and obtained video footage of Faqiri’s final journey from the showers to his cell, which Ontario’s Ministry of Community Safety and Correctional Services has so far refused to release. Sixty-seven people connected to the incident were interviewed. Nurses, ministry doctors, other jail staff and paramedics also provided statements.

“No correctional officer refused to speak,” the police report reads. Investigators also interviewed every inmate housed in the unit’s B-wing that day. “The interview of these inmates provided little information as to the events as they occurred,” the report said.

Despite what he’d seen, for nearly two years since Faqiri’s death, Thibeault kept quiet, afraid of the consequences of speaking out. Instead, he told police that night he’d slept through the entire incident — waiting for the right moment to break his silence.

“A thousand pounds of weight on top of him, on top of his lungs with pepper spray down his throat. There's a guard with a knee on his neck. There's his head being smashed off metal, his head being kicked off concrete. Punches, numerous punches.... They beat him to death. I don't I don't know how else to describe it. At all. There's no other answer.

“They viciously beat him to death.”

VI.

Just 15 seconds of the right pressure applied to the neck is enough to reduce the blood flow to a person’s head — enough to drop them to the ground to be handcuffed. With increasing pressure, a neck hold can turn into strangulation, constricting the airway and cutting off airflow.

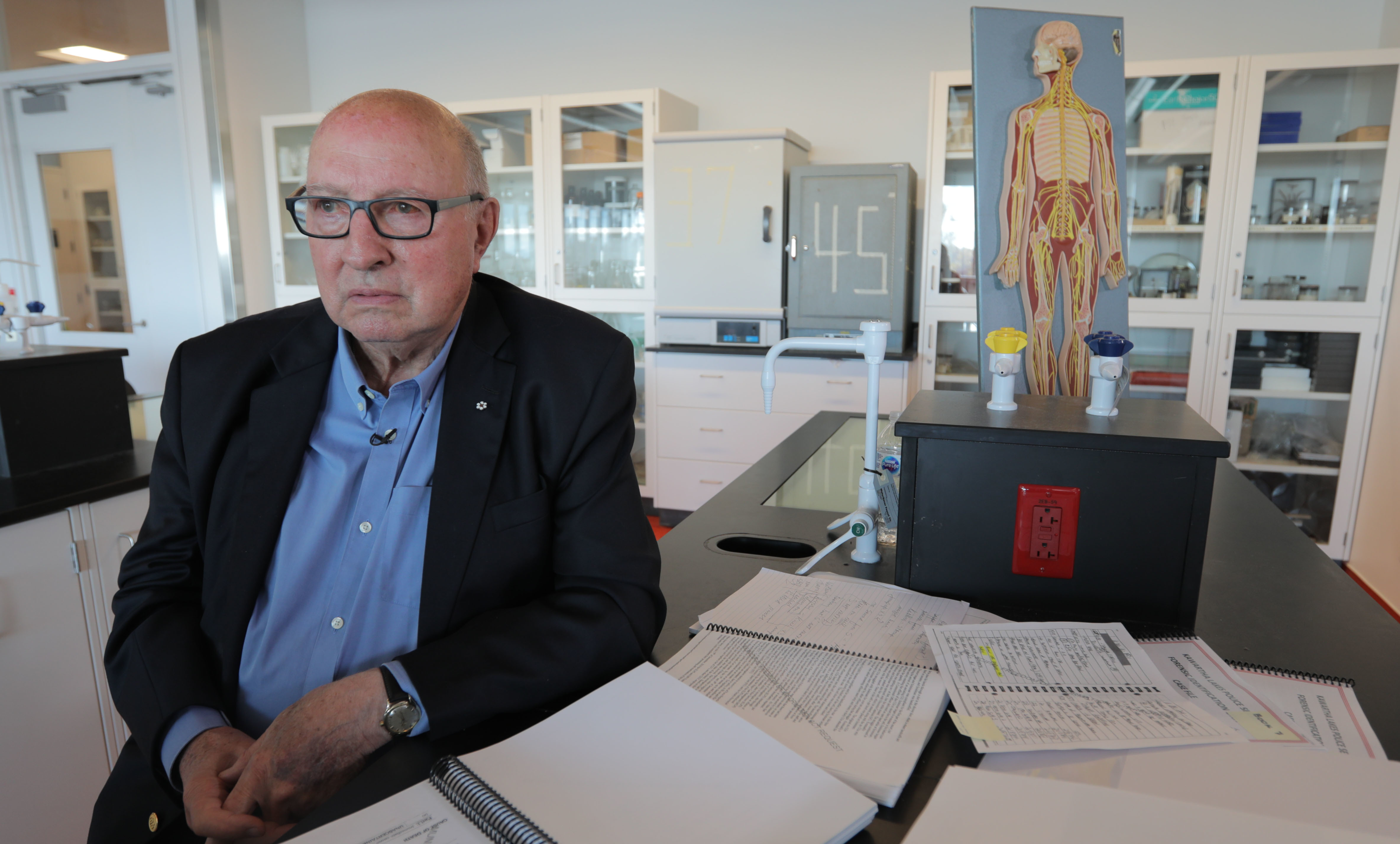

That, leading forensic pathologist Dr. John Butt believes, is what ultimately killed Faqiri.

As part of its investigation into Faqiri’s death, The Fifth Estate sought out an expert review of all the available evidence in his case.

Over a period of months, Butt, previously chief medical examiner for both Alberta and Nova Scotia, voluntarily pored over more than 1,500 pages of documents obtained by The Fifth Estate, including hundreds of autopsy photos, the post-mortem exam, toxicology reports, medication lists, police notes, 911 transcripts, inmate and jail staff interviews.

The Fifth Estate also shared Thibeault’s witness account with Butt — something he said only corroborates his view.

“Notwithstanding the fact that this postmortem examination, which I must credit the pathologist with, is a very skilled examination and a very good report … I would have said, on balance, the evidence of this case is that this is a restraint-related death due to neck and other compressive forces, notably on the chest and abdomen” he told The Fifth Estate.

Faqiri, Butt concluded, appears to have stopped breathing as a result of the pileup of guards while he was in a state of “excited delirium,” a medical term to describe when a person exerts themselves beyond the level they would normally be able, commonly associated with drugs like cocaine and LSD as well as situations where a person is being apprehended and has a fight or flight response.

Key injuries recorded in the post-mortem report support that conclusion, Butt said, including hemorrhaging of the deep strap muscles in the 30-year-old’s neck. “That is definitely due to some sort of pressure … it could have been hands on the neck, an arm around the neck, a foot.”

Those injuries, said Butt, were — contrary to the coroner’s report — likely caused by something other than blunt impact trauma. “I wouldn’t say you could prove that those were due to an impact, I think there’s more to it….

“If you put, for example, your hands around a person’s neck and squeeze, then you get the possibility, in fact that likelihood, of strangulation.”

Exactly what action could have caused those kinds of injuries is impossible to say, but according to Butt, the bruising to Faqiri’s neck and the hemorrhaging are “of concern.”

In fact, The Fifth Estate has found police notes from the days after Faqiri’s death do make reference to a “blow or pressure on the neck,” but no such reference is made in the official post-mortem report.

The possibility of strangulation appears to have been discounted by the coroner, Dr. Maggie Bellis, the day after Faqiri’s death, documents show. But together with Thibeault’s account of a correctional officer who’d held Faqiri down with a knee into his neck, Butt observed that enough evidence exists to suggest asphyxiation contributed to Faqiri’s death.

That evidence, said Butt, warrants reopening the investigation into Faqiri’s case. “Certainly a witness as evidence is not as good as the examination itself, but one would be a fool not to listen to this,” he said, adding Thibeault’s account lined up with the forensic information contained in the documents he reviewed.

For Yusuf Faqiri, a cause of death supported directly by witness testimony is “critical.” But the family wants more. “Our closure requires accountability. My family still does not have that,” he told The Fifth Estate.

“How is it that a mentally ill man loses his life at the very institution that's supposed to protect him? This family deserves accountability.... And my late brother, more than anybody, deserves that,” he said. “This was a human being who needed help.”

The documents obtained by The Fifth Estate show that in the days after Faqiri’s death, 15 correctional staff, including two operational managers connected with the incident, received suspensions. How long those suspensions lasted and whether they were paid or unpaid is unknown.

Ontario’s Ministry of Community Safety and Correctional Services would not confirm or comment on the suspensions, nor say if any disciplinary action was taken against the guards involved in Faqiri’s death.

Ministry spokesperson Brent Ross would only say the decision to suspend a staff member isn’t taken lightly and that whether or not to take disciplinary action is determined on a case-by-case basis.

“It would be inappropriate to speak to confidential human resources matters,” he said.

“Our internal investigation into the circumstances regarding the death of Mr. Faqiri has been completed but there remain some outstanding human resources-related matters that the ministry continues to address.”

The Fifth Estate attempted to contact all 15 guards as well as the deputy superintendent. None responded to the request for an interview. The Ontario Public Service Employees Union also declined to comment.

But with the investigation into Faqiri’s death now reopened, those involved could yet face criminal charges, according to Ontario’s chief coroner, Dr. Dirk Huyer.

When new evidence came to light in preparing for Faqiri’s inquest, Huyer said he contacted Kawartha Lakes police, the original body investigating Faqiri’s death, but didn’t reveal what the evidence was. Instead, the evidence was shared with Ontario Provincial Police to review as part of the new investigation.

Asked what he made of the cause of death found as part of The Fifth Estate’s expert review, Huyer wouldn’t comment, citing the integrity of the criminal investigation but did say “pathologists are always willing to look at new information or other ideas to see how that may or may not influence the opinion that they have.”

The office of Sylvia Jones, the provincial minister of community safety and correction services, declined to comment on the status of the investigation, Thibeault's account or whether any disciplinary action had been taken against correctional staff.

"Given the ongoing investigations into this matter and the confidential human resources issues involved, it would be inappropriate to provide comment," press secretary Marion Ringuette said in a statement.

VII.

On a mild, sunlit winter’s day, dozens of red and white roses pierced the pristine white of the snow blanketing the cemetery grounds where Faqiri was laid to rest, as a Canadian flag blew gently against a backdrop of bare branches and green pines.

That was more than two years ago.

In the time since, Faqiri’s brother Yusuf has channelled his grief into action, taking his brother’s story to university lecture halls, mosques and the Ontario legislature to shine a light on the plight of those with mental health conditions behind bars.

His fight isn’t unique — struggles like Faqiri’s have captured national attention in recent years, perhaps most notably with the death of Ashley Smith at Ontario’s Grand Valley federal women’s prison in 2007.

Today, the province of Ontario is facing a class-action lawsuit over the use of segregation for inmates with mental illness as well as the use of segregation for 15 consecutive days or longer.

According to the province’s most recent data on segregation placements in April and May 2018, 831 out of a total 3,998 placements ran 15 consecutive days or more. (The United Nations' acceptable limit is 15 days.)

Nine of those placements were for 365 consecutive days. Slightly more than 50 per cent of the placements involved people who had mental health issues. Meanwhile, the Central East Correctional Centre remains the province’s most complained-about facility for the third straight year, according to Ontario’s ombudsman.

As time wears on, so does the toll on his family — their only comforts now the memories they cling to of their “Soli.” For Yusuf Faqiri, it’s the little unassuming moments that replay in his mind. So close in age to Soleiman, his brother exists in virtually every childhood memory Yusuf clings to.

Video games. Competing for their mother’s attention. Getting on the wrong bus as kids on a family trip to Germany.

“I was nine and he was seven … in a country we didn’t know much about,” Yusuf said. “It was so scary. We held each other’s hands and we cried non-stop.” Years later they would laugh about that day, Soleiman claiming he was the brave one and that it was Yusuf who was scared.

For his younger brother Ali, the memory that remains most vividly is a story his mother told him of the time about a decade ago when she and her husband went to Mecca for the annual pilgrimage. With more than one million people around them, Soleiman wasn’t doing well on that trip about a decade ago, unable to sleep and becoming disoriented.

“At some point he kind of wandered off,” Ali said. Panicked, his mother and father began searching frantically for Soleiman. “Where is he? What’s going on? We’ve got to find him,” they said to themselves.

An hour passed. Two. Three. They began to worry something had happened.

As they made their way into the upper level of a mosque, suddenly they spotted Soleiman. Not agitated, not distraught — just seated in a circle of men, talking about faith.

It’s a painful contrast to their reality now.

“We were able to take care of him for 11 years. It took 11 days for him to be killed under government care,” Yusuf said through tears.

“We didn't expect for him to be given back to us in a body bag.”

With files from Nazim Baksh, Habiba Nosheen and Joseph Loiero