December 11, 2018

Nakuset sat across from me in a CBC studio in Montreal, headphones turned up, straining to hear her sister Rose Mary Murray’s voice on the other end of the line.

“Rose, are you there?”

There was a delay on the phone line from Austria, where we reached Rose Mary — a technical glitch that seemed unfair given how many decades the sisters had waited to hear each other speak.

I was hosting CBC Radio’s Daybreak program that day in July 2016, and all of this was happening live on the air.

On another line from Kenora, Ont., their other sister Sonya Murray was listening in.

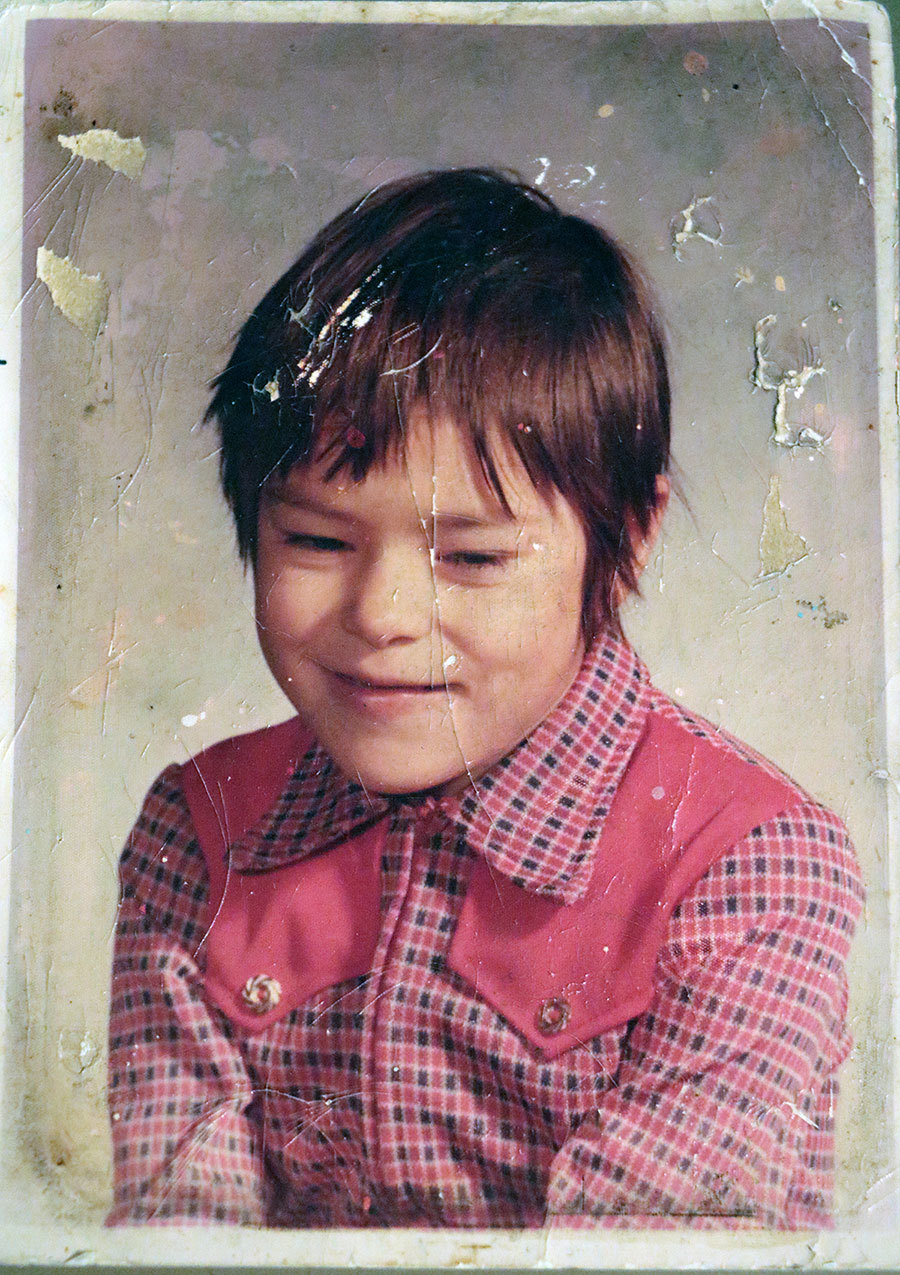

Sonya had never stopped looking for her sisters. She was the oldest of the three, and still held the memory of being lifted, along with Nakuset, from the twin bed they shared as children in Thompson, Man., and carried away in the middle of the night. That was more than four decades ago. Sonya was five at the time, and Nakuset was two.

Sonya remembered the two of them being placed in foster care together for a while — and then waking up one morning to find Nakuset gone.

The three Cree sisters would soon be scattered a world apart.

As heartfelt as that moment was, a reunion can’t always repair the harm of separation.

Nakuset would be adopted by a white family in Westmount, Que., as part of the decades-long removal of Indigenous children known as the Sixties Scoop. Sonya would be bounced around in foster care, at times returning to the sisters’ birth mother, a residential school survivor. Rose Mary, the youngest, ended up living in the Austrian town of Horn with the family of her biological father.

It took Sonya about 20 years to reunite with Nakuset. It took her another two decades to finally track Rose Mary down, thanks to Facebook.

CBC had done a number of stories on Nakuset — who only goes by one name — in connection with her experience in the Sixties Scoop and in her role as executive director of the Native Women’s Shelter of Montreal. In 2016, shortly after Sonya found Rose Mary, she approached CBC’s Daybreak to share the story of their reunion.

After an excruciating pause in the studio, Rose Mary’s voice finally came in from 6,000 kilometres away.

“I’m here! I’m still here! Oh my god,” she said, in a thick Austrian accent, audibly choking back tears.

“It’s like crazy overwhelming,” said Nakuset during the live interview. “I’ve already met Sonya, and Sonya is just amazing… I can’t say enough good things about my sister, Sonya. And I can’t wait to meet Rose.”

“It just feels complete,” Sonya said. Rose Mary “was the last missing piece of the puzzle.”

As heartfelt as that moment was, a reunion can’t always repair the harm of separation. These sisters, who had waited so long to find each other, would not have each other for long.

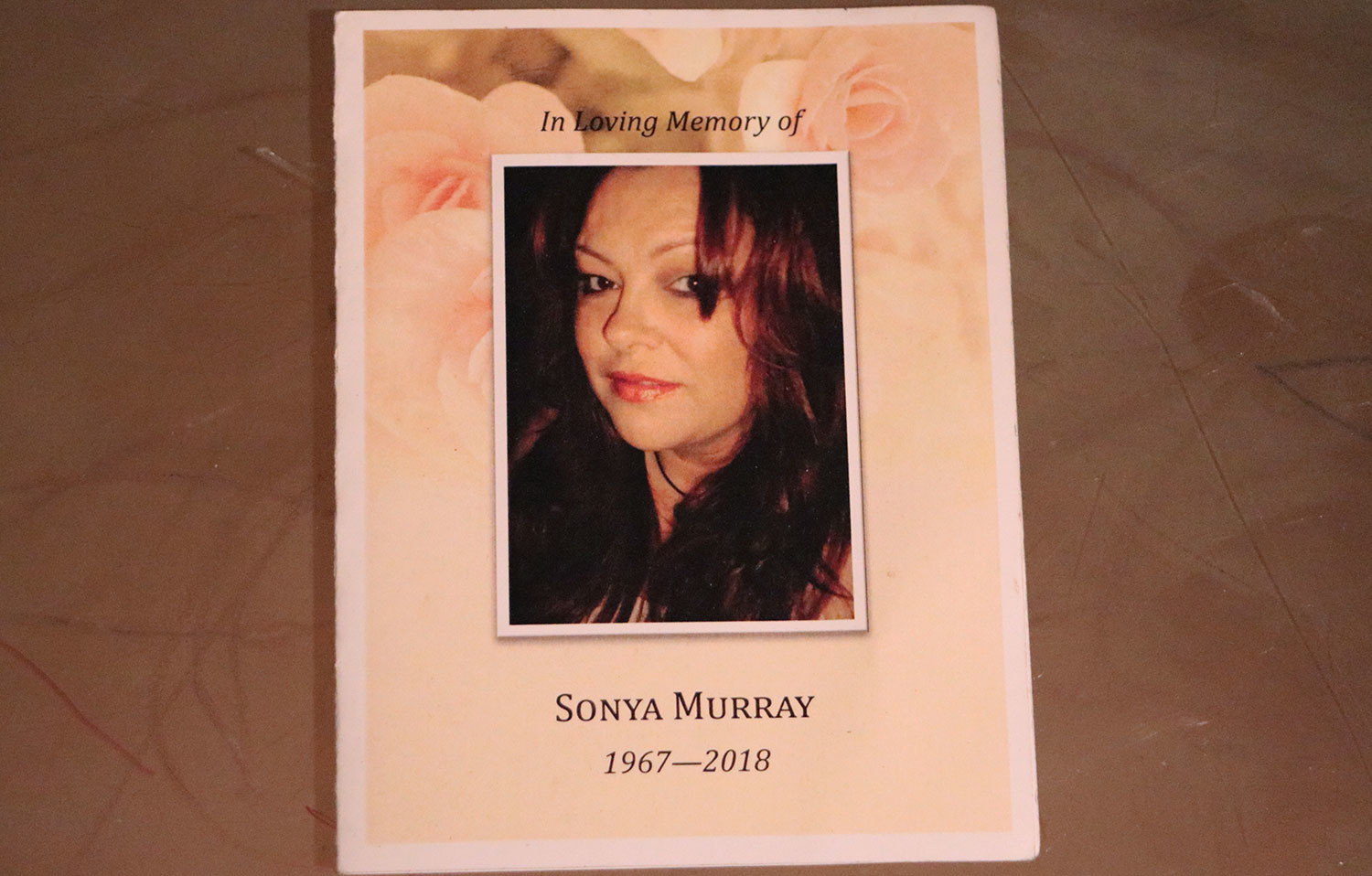

In August 2018, two years after that emotional reunion, Sonya Murray took her life.

II.

In her work life, Nakuset is called upon a lot to speak at rallies and conferences on Indigenous issues and to share her Sixties Scoop story. To consult, advocate, agitate, educate.

But it’s gotten a lot harder to do since Sonya died.

“I always have her in [my mind], but now I have to pull her out. Because I can’t be talking in a group and getting all emotional,” Nakuset said, tearing up.

Yet she can’t stop thinking about Sonya. She thinks about the trauma they both went through — being taken into foster care and then separated.

Finding each other, only to lose each other again.

Sonya and Nakuset came from a family of seven siblings in Manitoba. Nakuset said she believes all but Rose Mary ended up in care. (Rose Mary was not available to speak for this story.)

Nakuset’s adoption records paint a grim picture. When she was apprehended, the documents noted she had “an eye completely swollen shut, tender swelling on the back of the head… [and] bruise marks around the base of the neck.”

Sonya, at just five years old, saw herself as her sister’s protector. (Years later, Sonya told Nakuset, “I took a lot of beatings for you.”)

“I have a bit of survivor’s guilt because her experience was so bad,” Nakuset said.

Once in foster care, the sisters’ paths diverged. Sonya remembered going to sleep one night and waking up the next morning to find her little sister gone. When she asked what happened to Nakuset, she was told her sister “had to go home.”

In reality, Nakuset had been picked out of a catalogue of Indigenous children. She had been taken away to a new home more than 2,000 km away, adopted through Montreal’s former Jewish Family Services and placed with a white family in Westmount, Que. She grew up disconnected from her siblings and her culture.

Sonya, on the other hand, was never adopted. Her childhood was marked by instability. She went back and forth from foster homes to her mother, and then to group homes. She would only find out later in life what happened to her sister.

Their story reminds Nakuset of a book she and Sonya both loved called In Search of April Raintree. Written by Beatrice Mosionier, it tells the story of Métis sisters who are separated when they are placed in foster care.

The two characters “talk about their journeys apart, and as they get older, they find each other and then they continue the journey,” said Nakuset.

In the book, one of the sisters dies by suicide.

Nakuset said that when she was younger, “I remember, I was thinking, I hope that’s not going to be Sonya.”

III.

Suicide cannot be reduced to a single cause, nor is it an inevitable result of any given circumstances, as Quebec’s health ministry explains. That said, research has shown that the children and grandchildren of residential schools survivors — such as Sonya and her siblings — are at greater risk of suicidal thoughts, among a host of other negative health outcomes.

Sonya had expressed thoughts of suicide more than once, over the years, from her 20s onwards.

Nakuset said it’s clear that the past weighed on her sister. She thinks that reliving it, as Sonya did during the reunion interview on CBC, brought up a lot of emotions that she struggled to deal with afterwards.

“She’s the one I always called the holder of the memories, which I thought was very difficult for her, because she had a lot of not-happy memories,” Nakuset said.

Sonya spent a lot of time trying to suppress those memories, Nakuset said. But her sister had artistic talent, and she found a partial outlet through stories and songs. Nakuset had encouraged her to reach out to a publisher about writing a memoir.

In the lead-up to Sonya’s funeral this past August, her best friend, Shannon Shaw, found herself sifting through pages of Sonya’s song lyrics. The two women had become like family after Sonya took Shaw in when she needed a place to stay.

Shaw was trying to find something uplifting to include in the program for the funeral, something that reminded her of the strong, outspoken person she’d met more than 15 years earlier.

Instead, what Shaw read underlined the pain she had discovered in her friend as they’d grown closer.

“Sitting there, going through the songs, they were all so sad,” said Shaw.

Sonya wrote about the confusion she felt as a child when her sister was taken away.

In a piece written for the Indigenous advocacy website Working It Out Together, Sonya wrote about being physically and sexually abused in her childhood. She also addressed the feeling of yo-yoing back and forth between foster care, group homes and the home of her birth mother.

Sonya wrote about turning to drugs to forget the pain all that caused her. She wrote about being hospitalized at age 20 for expressing suicidal thoughts. She wrote about the shame she felt at not being able to take care of her three children the way she wanted to. But most poignantly, she wrote of feeling abandoned. Invisible. Left behind.

Nakuset reflects on losing her sister. (Jacques Poitras/CBC)

“I think it comes from when she was younger, that feeling of not being wanted by anybody,” said Shaw. “I think it’s something that she struggled with every day.”

In the web piece, Sonya wrote about the confusion she felt as a child, when her sister was taken away. Why was Nakuset leaving and not her? Was she being punished?

“Was it because I peed the bed too much? Why?” Sonya wrote.

“She always felt that she wasn’t worthy,” said Shaw. “It was anger and you could hear the hurt, too, in her voice.”

Sonya would carry the trauma of the Sixties Scoop her whole life — even if, by legal definition, she may not have been a part of it.

IV.

Though it’s called the Sixties Scoop, the removal of Indigenous children for adoption isn’t confined to that decade.

A recently settled class action suit covers Inuit and First Nations children who were placed in the care of non-Indigenous foster families or adoptive families between Jan. 1, 1951, and Dec. 31, 1991. Métis adoptees are excluded and non-status adoptees need to show they are eligible for status in order to receive compensation.

Already, about 6,000 people have applied for compensation through the settlement, and thousands more are expected to do so before the deadline on Aug. 30, 2019.

For many survivors, the process is bringing up painful memories.

“The settlement has just literally picked a scab for a lot of people who… have unresolved trauma,” said Colleen Cardinal, co-founder of the National Indigenous Survivors of Child Welfare Network (NISCWN) and herself a Sixties Scoop survivor from Saddle Lake First Nation in Alberta.

For some survivors, finding adoption records in order to prove their claim would mean getting in touch with their adoptive families, from whom they may be estranged.

Or their records could simply be wrong, like Nakuset’s. Someone wrote down on her adoption records that she is Métis, when she is actually Cree, from Lac La Ronge, Sask.

The claims administrator is touring the country, starting this month, trying to help survivors track down their paperwork and file their claims. But the question of who exactly will be eligible when the dust settles is unclear. In order to receive compensation, a claimant must have been adopted or made a permanent ward of the state.

That’s where things got muddy for Sonya Murray, who bounced around in foster care, but periodically went back to live with her birth mother before returning to care.

“She felt like she wasn’t entitled [to compensation] because she’d always gone back home,” said Shaw, who had spoken with Sonya about the settlement before she died.

The agreement does include an exceptions committee that will review all cases that don’t fit the criteria at first glance. But the underlying principle is that the settlement is offering compensation specifically for the loss of Indigenous identity and culture.

Cardinal said that cultural loss is clearer in the cases of adoptees like Nakuset, who were moved to other provinces, had their names changed and often their birth certificates altered, as well as permanent wards, who never had any contact with their birth families.

Cardinal said many people were in situations similar to Sonya’s. She estimates about half of the survivors she’s met through the national healing gatherings organized by her network were never actually adopted, and spent their childhood in anywhere from two to 20 different foster homes. Some, like Sonya, also went back to a birth parent for a while.

“Using the word ‘adoptee’ can be really triggering for them, because they’re like, ‘Well, we weren’t adopted,’” said Cardinal. “They’re kind of feeling left out of the whole process [of the settlement]. They don’t want to be forgotten, either.”

V.

Sometimes, when Nakuset thinks about what she and Sonya went through, she wonders how much has changed for Indigenous children in care today.

Indigenous kids still represent nearly half of children under 14 in foster care in Canada, despite the fact that they make up only seven per cent of the under-14 population, according to Statistics Canada.

Fewer than half of the Indigenous children in youth protection are placed with at least one foster parent who is also Indigenous. Fewer still have a foster parent with the same Indigenous identity as them.

(CBC)

“Are we repeating the same pattern? And at what point do we stop it?” Nakuset asked.

There are some signs of change on the horizon: Indigenous services minister Jane Philpott just announced legislation that would see the federal government hand over authority over child welfare to Inuit, First Nations and Métis governments in order to address the “humanitarian crisis” of Indigenous children in care.

“There’s so much work to do. Sometimes I feel like I’ve barely scratched the surface.”

Nakuset, who has fought for years for the rights of Indigenous children in Quebec’s child welfare system, questions how that will change the day-to-day reality for the urban Indigenous population she works with.

She’s heard announcements before. She’s seen agreements signed, only to have them rolled back or sit on a shelf gathering dust.

“There’s so much work to do. Sometimes I feel like I’ve barely scratched the surface,” Nakuset said.

But she keeps trying. In some ways, she has become even more determined to succeed — to try to make sure that no one else ends up losing their big sister.

This is one of a series of stories from CBC Montreal examining the Sixties Scoop and its echoes in the Indigenous experience of the child welfare system today. You can read more from Nakuset on why she decided to tell her sister's story.

Where to get help:

Canada Suicide Prevention Service

Toll-free number: 1-833-456-4566

Text: 45645

Chat: CrisisServicesCanada.ca

In French: Association québécoise de prévention du suicide

Toll-free number: 1-866-APPELLE (1-866-277-3553)

Toll-free number:1-800-668-6868

Live Chat counselling: www.kidshelpphone.ca

Canadian Association for Suicide Prevention: Find a 24-hour crisis centre

If you're worried someone you know may be at risk of suicide, you should talk to them about it, says the Canadian Association for Suicide Prevention.

Here are some warning signs:

- Suicidal thoughts

- Substance abuse

- Purposelessness

- Anxiety

- Feeling trapped

- Hopelessness and helplessness

- Withdrawal

- Anger

- Recklessness

- Mood changes