March 30, 2019

There were so many times in the past that she almost died — after the shooting, or the miscarriage or during one of her many stints in hospital.

So it was understandable that as Shakila Zareen waited to be wheeled into surgery at one of Canada’s top hospitals, in an operation that had been planned for months, that she suddenly dissolved into tears, whispering that maybe she wasn’t as strong as she often appeared.

“I am very scared,” the 23-year-old woman quietly told her mother, Sharman. “If something happens to me, please be happy and have laughter in your life. And I’ll always be with you.”

Six years ago, Sharman Zareen had found her daughter lying on the floor in their home in Mazar-i-Sharif, in northern Afghanistan, covered in blood after Shakila’s husband shot her in the face. Now, in the pre-operative ward at Vancouver General Hospital, Sharman tried to comfort her daughter on the cusp of her 10th operation since that night.

“You are out of danger now,” the 48-year-old woman said in their native Dari language, shedding her own tears. “There were horrific days and it was frightening, but you are in much better condition now. You are a strong girl. I believe in you.”

Sharman held her daughter, then let go and watched as Shakila’s gurney rolled down the hall and into the operating room, where two surgeons and a team of nurses would spend the next 14 hours trying to rebuild her face.

Shakila has been through so much over the past six years: violence, pain, disfigurement, disappointment and uncertainty. But this is a young woman with extraordinary resilience — one, who, despite all that has happened, refuses the label of victim.

II.

Shakila Zareen grew up in Baghlan, north of Kabul, where she remembers climbing trees, picking figs and apricots to sell in the market. She also kept two sheep that she regarded as pets.

She attended school until she was 12 years old, with the support of her mother and father, Zareen (like many Afghans, he went by a single name). The couple had four daughters and two sons.

Zareen was a medic with the Afghan army, but was badly injured in a shootout with the Taliban before Shakila was born. After that, he could no longer work. Shakila said her father was largely bedridden, and couldn’t walk without crutches. Without Zareen’s earnings, money was tight.

“There were times when I did not have enough food and I would go hungry in order to feed the family,” Sharman said, recalling times when she resorted to “boiling chickpeas and potatoes for dinner.” To help out, Shakila went to work, weaving carpets with other children.

With her husband disabled, Sharman said she could do little to protect her daughters from the Afghan men who came looking for wives. Shakila was just 16 when her brother-in-law forced her to marry a man 14 years her senior (and one of Shakila’s cousins). In talking to CBC, Shakila didn’t want to name her husband or her brother-in-law, for fear of retribution. She did say, however, that her brother-in-law is a “powerful, dangerous” man.

"Blood was pouring into my hands. I thought Shakila was dead"

Shakila was so concerned about the forced marriage that she tried to run away from home, but “men with guns surrounded the house.” She had no choice but to marry him, which she did in 2013.

She said the rapes and beatings began on her wedding night.

Shakila eventually took the bold step of reporting her husband to the police; later that same day, they tipped him off. That night Shakila’s husband arrived, shotgun in hand, at Sharman’s home, where Shakila was staying. Sharman said she was in another room, praying, when she heard screams unlike any she had heard before. She rushed to the room to find Shakila on the floor.

“Blood was pouring into my hands,” her mother said. “I thought Shakila was dead, that she had been killed,” Sharman said, burying her head in her hands at the memory. (Sharman was initially reluctant to be interviewed for this story, fearing she would be blamed for failing to do enough to keep Shakila from harm.)

Although the shotgun pellets destroyed half of Shakila’s face, she was alive. Sharman got her into a taxi, and the two of them embarked on a seven-hour journey to a hospital in Kabul.

In the midst of this trauma, Shakila had another problem. Unaware she was pregnant, Shakila miscarried.

According to her mother, Shakila went into a coma for a month. As her daughter lay in a hospital bed, Sharman, full of fury, went looking for justice. She went to the police as well as to the gates of the presidential palace in Kabul, loudly demanding that someone arrest her son-in-law.

An aide agreed to meet her.

“He said that there is not anything we can do. There are thousands of girls who have their noses and ears cut off every day,” Sharman recalled.

“Nobody cares in Afghanistan, nobody investigates, nobody cares about women’s rights. Afghan women are trampled and oppressed.”

III.

Shakila had lost an eye, most of her nose and ear. X-rays showed her teeth and jaw were destroyed.

Her case attracted media attention, and in the wake of stories about the shooting, the Indian government reached out to the Zareen family to offer free medical care and refuge. Local Afghan law enforcement spurned Shakila's pleas for protection from her husband, but once her critical medical condition became known, government officials stepped in to ensure she could travel to India to get more care.

And so Shakila, her mother and her younger sister Samira left Afghanistan and flew to Delhi, India. (Shakila’s father died shortly after her wedding.)

Shakila recalled being excited at the prospect of travelling to India for surgery, hoping it would ease her pain and restore her appearance. But the doctors there knew it would be a staggering task just to get her to the point where she could properly breathe and eat.

Fiona Addleton, an American woman who befriended Shakila in Delhi, said she believed the doctors in India did the “operations that were necessary for her survival, initially treating the wounds and keeping her alive.”

She ended up undergoing nine surgeries over the course of three years in Delhi. They involved skin grafts from her legs, which left scars. She got a new prosthetic left eye, but it didn’t fit properly, and drooped down her face.

Despite all this, there were happy moments. An Indian newspaper arranged to fly Shakila from Delhi to Mumbai to meet one of her teenage crushes — Bollywood superstar Salman Khan. The newspaper reported that Shakila promised to visit Khan again after she regained her “beautiful looks.”

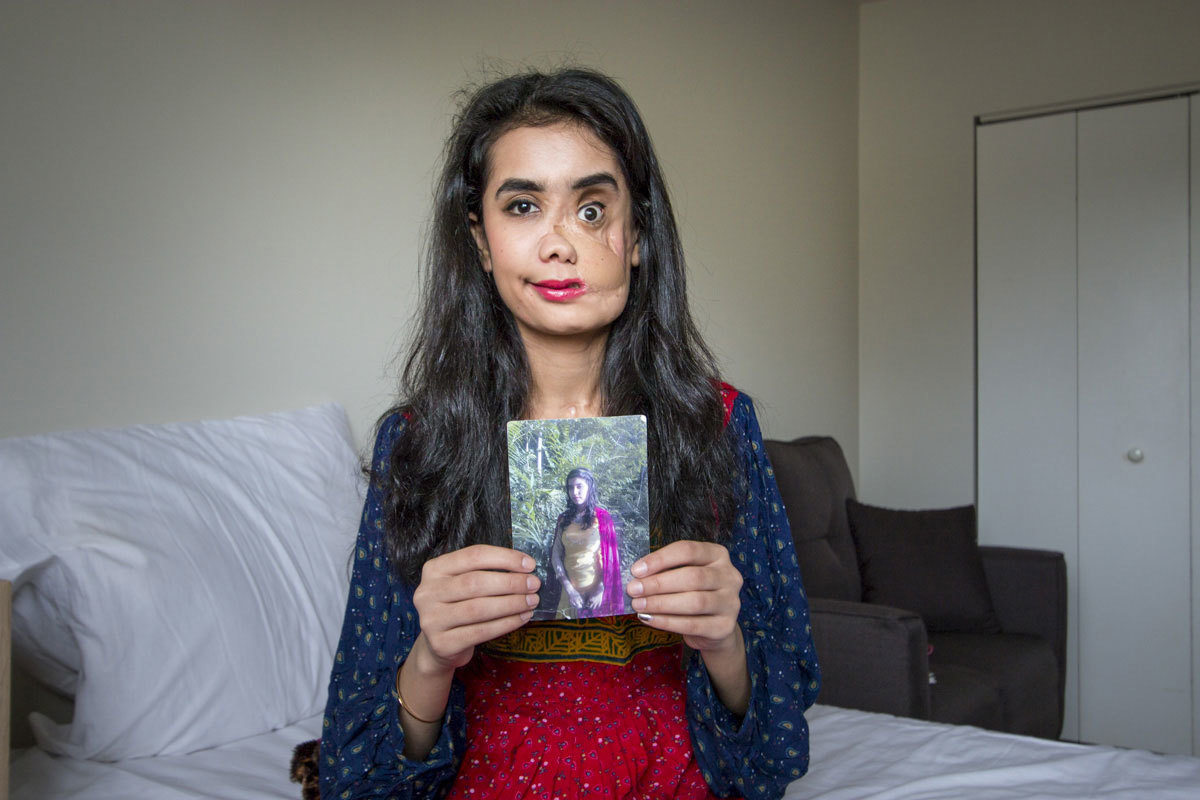

Yet daily life in Delhi was no Bollywood dream. In public, Shakila hid her disfigurement with an eye patch and draped her long, dark hair over her face. The constant taunts from men in the street took a toll on her spirit. One remark, from an Afghan man speaking Dari, still stings.

“He said, ‘Hey, blind girl, get away from me. You are so ugly, I can barely look at you.’ I felt so bad, because how could one Afghan, another person ... say this to me? I am a human being,” Shakila said.

“I pretended I didn’t hear him, but in my heart, I was crying.”

Meanwhile, there was a stream of threats coming from her husband and brother-in-law back in Afghanistan, who called vowing to find her and kill her. The family didn’t think that India was far enough away, so they applied for asylum in the United States.

Their application was accepted in 2016, when Barack Obama was still president. But it was revoked after Donald Trump came to office. The U.S. deemed her a “security risk,” because of her husband’s ties to the Taliban. (Sweden also rejected her, based on the U.S.’s demurral.)

In the wake of that, Shakila, Sharman and Samira were fast-tracked to Canada, and arrived in Vancouver on Jan. 31, 2018.

IV.

The most striking difference in Shakila’s appearance when she moved to Canada was her decision to remove the eyepatch. She said it was a statement that she felt safer and more confident in her new country.

But the aftermath of her trauma lingered, according to Friba Rezayee, a 31-year-old Vancouver resident who befriended Shakila and her family after she saw her story on CBC.

Rezayee, who is also from Afghanistan, recalled their first meeting as “very intense.”

They went to a Tim Horton’s for coffee. “The disfigurement was obvious on her face. I felt terrible for her, I felt awful, but I knew deep inside that she was very, very strong.” As they waited for their orders, something happened that tested Shakila’s strength.

“There was an angry man, shouting — maybe he had a bad day — and she saw him and freaked out,” Rezayee said. “She got so scared, she started shaking, and I held her hand and hugged her and said, ‘It’s OK, it’s going to be OK, he’s not hurting you.’”

It was an indication of the challenges ahead.

Rezayee, an activist who campaigns on behalf of Afghan women in Vancouver, said Shakila’s experience with her husband is, sadly, not unusual.

"The problem in Afghanistan is that there is no law enforcement that will punish men who do such brutal action against women."

Afghanistan is still ranked the worst place in the world to be a woman. Rezayee cited a UN report that claimed 87 per cent of Afghan women face some form of violence and 60 per cent experience multiple acts of harm. For the perpetrators, there is impunity.

“The problem in Afghanistan is that there is no law enforcement that will punish men who do such brutal action against women. Men are the kings of their lives,” Rezayee said. Indeed, Shakila’s husband served only several months in jail in Mazar-i-Sharif before being released.

Shakila is now studying English, but is hampered by poor vision in her remaining eye. In a candid moment, she revealed that she was careful not to lean over her books or notes when she was in class for fear her ill-fitting prosthetic would fall out.

Eating, too, continues to be difficult, because of the constant pain in her mouth and the loss of so many teeth. Nightmares disrupt her sleep, though less often than before, she said.

Rezayee has tried to help Shakila do more than just live in her new city. For one thing, she has taken her and her sister dancing. Others who have reached out to the family have taken them to Vancouver parks and beaches, helping them enjoy a sense of freedom.

Shakila has embraced her new life, learning to play foosball, going out alone, applying makeup with care and wearing the kind of fast fashion so many other young women love: jeans, T-shirts and eye-catching dresses. Shakila is even exploring the idea of modelling, with friends who have helped her do unofficial fashion “shoots.”

For now, though, her focus is on other areas.

V.

Shakila has not only enjoyed a greater freedom in Canada, but her harrowing experience has turned her into an activist.

Last June, she flew to Ottawa, where she was invited to speak at a national conference of women working with survivors of domestic violence. In halting English, she delivered a message of strength — a warrior from a faraway land using words as weapons to inspire Canadian women.

“Do not be silent in the face of violence. It is up to you to fight and you can. I am proud of all women. We are the superwomen,” she said, winning a standing ovation.

She did not stop there, carrying the energy from that room to a meeting on Parliament Hill with immigration minister Ahmed Hussen. Shakila, who was once a woman who with no power, was now walking the halls of power.

But before she met Hussen, she saw another Afghan refugee: Maryam Monsef, at the time the minister for the status of women. Monsef embraced Shakila and the two fell into an emotional, excited conversation in Dari about the plight of Afghan women.

“You are so strong,” Monsef said, praising Shakila for speaking out against violence.

Once Hussen entered the small meeting room just below the House of Commons, Shakila wasted little time, informing him of a list of needs not being met for many refugees. For one, access to therapy for victims of trauma. Shakila has had just 10 sessions with a counsellor in the time she has been in Canada, courtesy of a pilot program. Unlike other nations, such as Australia, there is no dedicated funding to provide longer-term intense treatment for refugees who come to Canada with post-traumatic stress disorder.

Shakila also shared a first-hand account of the financial challenges. As Government Assisted Refugees (GARS), people like her are entitled to roughly $1,100 each per month for 12 months, including a transit pass. But in February, they lost the federal support, and now live on roughly $700 each. Since the family's rent is $1,600 plus utilities, money is tight.

The Zareens are on the list for subsidized housing, and given Shakila’s medical challenges, she is a priority. But there are 20,000 others also waiting, and there is no certainty about when they will find affordable shelter.

Shakila wants to work, but her condition makes that impossible. Sharman wants to find a job as a cook or in a garden centre, but her English is limited. Her younger sister is in high school, and has done some part-time work in a restaurant.

Hussen listened, but offered no promises. Shakila left Ottawa buoyed by her new role as an activist and advocate, but flew back to Vancouver with a still uncertain future.

The return to reality included a trip to the local food bank in a church basement in a Vancouver suburb.

Always on her mind: when would she get the surgery that would restore her face?

Volunteer Theresa Rasquinha welcomed Shakila and her mother with open arms, quickly discovering they could communicate in a shared language — Hindi, which the Zareens had picked up during their sojourn in India.

“I’m glad you are visiting us,“ Rasquinha said, gesturing toward a table with two boxes filled with tinned foods, rice, beans and other items. “This is what we have for you, because I’m not sure what you would want.”

Rasquinha took them into the pantry where the shelves were filled with more tins of food. Shakila moved in close to be able to see what was on offer. She chose the chickpeas.

The food bank’s generosity extended to basic items the Zareens still didn’t have after months in Canada — sheets and blankets among them. Shakila also asked if she could take a giant stuffed toy bear for her sister. She smiled as she carried it out.

What really moved them, though, was Rasquinha’s special effort to go out and buy traditional Afghan flatbread for them.

“Thank you,” said Sharman as she looked over the bounty.

Shakila smiled as she picked up one of the boxes to carry out: “I am strong.”

Throughout all of this — the trips, the high-profile appearances and the day-to-day life in Vancouver — one thing Shakila was almost always on her mind: when would she get the surgery that would restore her face?

VI.

Weeks after she arrived in Vancouver, Shakila met Dr. Kevin Bush, one of the city’s top reconstructive surgeons, in a cramped examination room at Vancouver General.

Shakila had brought a thick file of X-rays and medical reports from her time in India. She also brought an interpreter in order to avoid any misunderstandings.

Shakila’s external scars were easy to see. The internal ones surfaced only after Bush started poking and prodding. Probing inside her mouth, he noted how much was missing: bones, teeth, the eye socket, part of her jaw. It was why her prosthetic eye hung so loosely on her face.

Bush then asked Shakila what she wanted to know. She turned to her interpreter, telling him what was more important than anything else. The interpreter paused after he heard the question. He took time to compose himself, but choked up as he uttered Shakila’s words in English.

“Will I get my face back?”

Shakila stared intently, awaiting the answer. Bush didn’t pause, answering right away.

“I think we can do some things to make things better for you. The honest answer is that we can’t get you right back to where you were before,” Bush said. “I think if you said, ‘Am I going to look exactly the way I did before my injury,’ I’m going to have to tell you that that is not going to be possible.”

A tear rolled down Shakila’s cheek as she listened to the interpreter telling her what she did not want to hear. But she knew she had only one choice. She had to move forward with the tests and appointments.

Shakila talks, through an interpreter, about her hopes for the surgery.

By December, Bush had developed a detailed plan for the operation. A three-dimensional view of Shakila’s skull was displayed on the screen in his office as he explained the first surgery, in which he was going to rebuild her eye socket and upper cheekbone. At the same time, a second surgical team would remove the fibula from her right leg, using that to complete the reconstruction of the area.

“We can’t give her another eye,” Bush told CBC. “What we can do is try to support a new prosthetic eye, so it’s not just hanging in the soft tissues. And that will give her a better look.”

Ten days later, Shakila, her mother and sister awoke before 5 a.m. to travel to the hospital. They had not slept much the night before, restless with both fear and anticipation.

Once Shakila had been wheeled into the operating theatre and put under, Bush focused on Shakila’s face, retrieving pieces of her shattered cheek to help rebuild the socket. A second doctor took bone from her lower leg to do the rest. The atmosphere was calm, workmanlike. At times, the only sound was the beeping of her heart monitor.

In all, it took 14 hours to complete. Afterwards, Shakila was transferred to a warm room in the intensive care unit. To promote healing, a tube was inserted in her throat to help her breathe.

It took weeks for her to recover. Once the swelling subsided, Shakila’s new cheekbone and eye socket lent more symmetry to her appearance. To her frustration, though, she had to again wear a patch over her eye. The old prosthetic no longer fit, and a new one would have to await further operations to rebuild her nose and jaw.

VII.

On June 6, she is supposed to get a new nose. That will be another complex operation, in which the doctors will use skin from her forehead and bone from her skull. No word yet about the third, and hopefully, final major surgery.

None of this is easy: the waiting, the pain, the remaining scars and continuing uncertainty. Yet Shakila has come to bear all of this with determination and poise, especially in public.

On a Saturday evening in early March, three months after Shakila’s surgery, women in the Vancouver suburb of Surrey gathered at a glitzy gala honouring South Asian women for their business and charitable work, as well as for their character.

“The 2019 Shakti award for courage goes to Shakila Zareen!” boomed the mistress of ceremonies as the room erupted in applause.

Shakila strode to the podium wearing a demure black dress. Though the bandage remained over her eye, she projected confidence.

There are many challenges ahead, but on this night, Shakila was beaming and bowed gracefully as a bouquet of flowers was placed in her arms.

Returning to her table, she embraced her smiling mother.

Additional reporting by Sylvène Gilchrist

If you would like to know more about Shakila’s story, please contact laura.lynch@cbc.ca or sylvene.gilchrist@cbc.ca.