June 23, 2020

Editor’s note: On Jan. 4, 2023, a justice of the Alberta Court of King's Bench released her report into Serenity's death. In that report, Justice Renee Cochard reviewed information, including the results of subsequent investigations, and outlined various "misconceptions" about the girl's condition at the time she was admitted to hospital. The report includes findings that there was no sexual abuse, and that an interpretation of a nurse's note which read “?0 hymen observed during catheter insertion” indicated her hymen was missing is incorrect.

Maybe it all started with a punch in the face.

She was 22 years old on that January day when the father of her youngest child tracked her down, according to caseworker notes detailing the interaction that would later be filed in court.

He had just been released from prison. They argued, and he slugged her.

Two days later, she walked into an RCMP detachment to file a report about her abusive ex-boyfriend, who had a criminal record so violent that caseworker notes warned staff to bring a police escort if he had to be approached.

While at the detachment, records say, the young mother, her left eye purple and swollen, told victims’ services staff she couldn’t afford diapers or formula for her seven-month-old daughter, and was afraid to go home.

The report she filed triggered a chain reaction, and soon a social worker from Child and Family Services (CFS) set up a meeting to go see the Indigenous mother and baby. The notes from that meeting on Jan. 10, 2011, show that the conversation between social worker and mother was a negotiation.

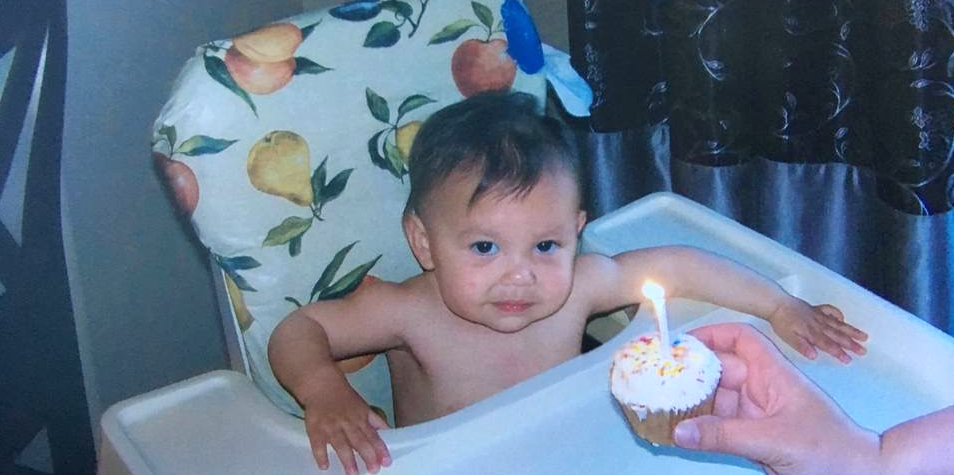

The worker wrote that the baby, Serenity, looked healthy, with attentive brown eyes framed by dark, wispy hair and chubby cheeks. Her mother had already been warned to stay away from her violent ex-boyfriend, according to case notes filed with the courts.

“My social worker had told me that if anything happens with Serenity’s dad, please make sure to call the cops,” the mother told CBC in a recent interview. “Do the right thing.”

But, according to the records, the worker was now suggesting Serenity be put into provincial care. The mother’s two older children by a different father had already been taken, and social services had warned her she was not making the improvements required of her as a parent.

The mother resisted, at first. Life with Serenity had been going well. Her daughter, born on June 23, 2010, had been happy in their short time together.

“Her favourite thing to do was to eat,” the mother said recently. “We just kind of hung out. Me and her.”

According to CFS records, when the social worker noted the mother had missed several appointments with her family support worker, the young woman tried to defend herself.

She insisted she hadn’t missed appointments, then offered excuses, saying she had a lot to do, many expectations to meet.

If she wasn’t attending all her appointments, she was asked, wasn’t she putting her baby at risk? And wasn’t it true she was struggling to provide for her daughter? That she couldn’t afford diapers or formula?

It must be hard to care for the baby while trying to get your life on track, the worker said. So, really, what would be best for Serenity?

The mother finally agreed that it might make sense to surrender her daughter, just until she got back on her feet.

She wanted assurance she would get the baby back. The worker provided it: if the mother attended all appointments — meeting with family support workers, getting treatment for her addictions, seeking help extricating herself from a pattern of abusive relationships — she could regain custody.

It was 4 p.m. by then, and mother and daughter were granted one last night together.

The next morning, at 9 a.m., two social workers arrived. The apprehension order, later filed with the court, cited three reasons for taking the baby into care: the risk of exposing the little girl to violence; her mother’s inability to provide for her; and the young woman’s positive test result for marijuana.

“I hope this will spark something.” — Serenity's mother in a recent interview

More than three years passed before a judge finally restored custody of Serenity to her mother.

By then, the little girl lay dying in an Edmonton hospital bed. By then, the only thing left for the mother to do was say goodbye, and sign the papers to remove life support.

Serenity died on Sept. 27, 2014. In the years that followed, the cloudy circumstances that preceded her death — along with photographs that showed an emaciated and bruised child on life support — drew a firestorm of media and public criticism.

Protesters rallied on the steps of the Alberta legislature to call for justice, while inside politicians remade child welfare law, fashioning a new provincial ministry and crafting a series of recommendations they pledged would create better protections for children in care.

A criminal charge of failing to provide the necessaries of life was eventually laid against Serenity’s kinship caregivers. It was later stayed before the trial began.

Several lawsuits have since been filed.

On Aug. 13, 2020, the window for that criminal charge to be reactivated will close. As her hope for justice expires, Serenity’s mother is skeptical that any person or organization will ever be held accountable for what her daughter went through.

Though her expectations are low, she says she’s not going to give up on advocating for her child.

“I hope this will spark something,” she said in a recent interview.

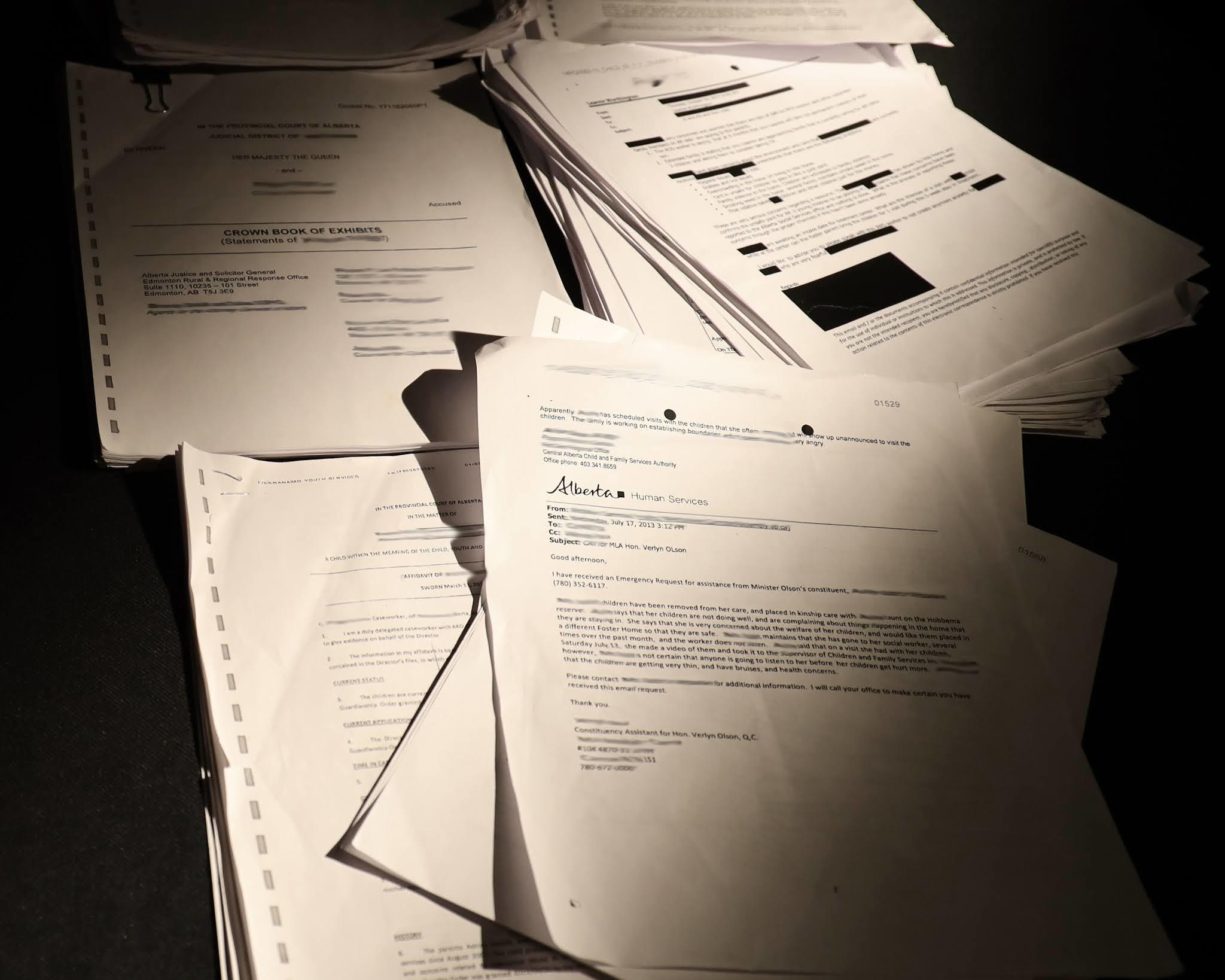

Many questions about what happened to Serenity remain unanswered. CBC went to court to argue for access to thousands of pages of documents — including reports from her foster parents, child intervention files, police investigation records, and medical and court documents — filed as evidence at the 2019 preliminary hearing for her caregivers.

While a trial determining the truth of the allegations made in the documents never took place, those records, cited throughout this story, paint the clearest picture thus far about the little girl’s life, and the circumstances that led to her death.

When she was first taken into provincial care in January 2011, Serenity was placed in a home with a Sylvan Lake family, where she quickly bonded with her foster parents, according to records from that time.

CBC requested an interview, but the couple said they’d been advised by legal counsel not to speak, for confidentiality reasons.

Progress reports filed with Crossroads Family Services during Serenity’s time in the home, and later filed in the criminal matter against her caregivers, shed some light on Serenity’s short life in the system.

She was reported to be an affectionate baby who loved cuddles, singing and dancing, and playing peek-a-boo. Always smiling.

“We enjoy every day with Serenity,” the foster mother wrote.

On a family camping trip, Serenity crawled around in the grass, picking up leaves. It became apparent she liked to do things her own way, her foster mother reported.

As she grew from baby to toddler, Serenity hated to sit still.

“She is walking!!” her foster mother wrote in a 2011 report. “She actually walked for a couple days, now it’s more of a sprint.”

The reports also provide updates on her health: in June 2011, around her first birthday, she was taken to the doctor to have her immunizations updated. “She’s quite tiny for her age,” the foster mother reported after the doctor’s visit; at the time, Serenity weighed about 17 pounds and was 27¾ inches tall.

For years, reports that social workers filed about Serenity’s mother were damning, citing her addictions, her pattern of falling into relationships with violent men, her cognitive impairment — all arguing she was an unfit parent.

The notes caseworkers made during the young mother’s visits with her children suggest she was under an intense level of scrutiny as she battled addiction and poverty and dealt with domestic abuse.

Records from a visit in September 2012 state that the mother showed up feeling sick and felt guilty, but told the supervising social worker that she needed to see her children and would keep her distance.

The worker noted “a meal had not been planned,” and that the mom spent the first hour of the visit trying to order food for less than the $50 she could afford. The father of Serenity’s siblings arrived, and the social worker noted he was “smelling like mouthwash.”

“I miss you every second I am away from you,” the father reportedly told his children. He listened to music with the two eldest, while the mother tried to read a book with Serenity.

Then, the report from the visit states, the dad and two older kids began wrestling on the floor.

The social worker watched them and started making notes. Serenity’s mother asked her what she was writing.

When the social worker told her it didn’t matter, the mother persisted.

“I cannot fix it if you do not say,” the mother reportedly said, and then yelled at the father and kids that she couldn’t hear the worker.

“Isn’t that what you are here for, to tell us what to do?” the mom asked.

The worker replied that that wasn’t her job.

“I just report on parenting. I report what I see and am not responsible for the interpretation that is made,” the worker said, according to her notes.

At the bottom of the report, in the section titled ‘Family strengths,’ the worker wrote, “none today.”

At the same time, assessments of the mother found she wasn’t making progress, and hadn’t been willing or able to maintain a permanent residence.

In an interview, the mother told CBC that no matter what she did back then, nothing was good enough for her social worker.

She said she went to rehab for cannabis use, and tried to keep up with the demands for meetings and drug testing.

“I did the things that they asked,” she said. “I still have reports put away in my closet stating that I did my family counselling. And at the end of the day, my social worker always had something else for me to do, and it wasn't good enough for her.”

By then, as the court records show, work was already underway to transition Serenity, and her older siblings, who were in another foster home, into kinship care.

The plan was for all three children to live together with their mother’s aunt and uncle.

In Alberta, kinship care is an alternative to foster care. Children and youth are placed with family members, such as a grandparent or aunt, even close family friends.

Prioritizing placement of Indigenous children with family members or within their own communities is a feature of a new federal law that grants Indigenous communities jurisdiction over how intervention programs for their own children will be run.

The new national standards affirm the importance of cultural and familial connections for Indigenous children, and enforce giving more notice to families and communities when decisions are being made about placements and custody.

Keeping children with their siblings, and prioritizing placing them with families and within their communities, is also key.

“She’s a bubbly, silly girl who seems to be developing right on target with healthy attachments” — Serenity's foster mother wrote in a progress report in February 2013

According to records filed in the preliminary hearing, the first time the prospect of having the three children placed with the aunt was raised Nov. 3, 2011, at a meeting with a designate from the family’s First Nation.

But several months passed before the aunt submitted the kinship care application and an assessment was completed.

Foster care records filed in court show that at a doctor’s appointment on Oct. 31, 2012, Serenity weighed 26 pounds. She was 28 months old.

According to CFS records, Serenity’s mother continued to have visits with her children throughout this period, though she was out-of-province at one point. In November 2012, social workers noted the mother was pregnant with her new boyfriend’s child.

Meanwhile, Serenity was branching out socially, saying "Hi" to strangers, and was at ease with her foster family, according to records. Potty training plans were mentioned, and the foster mother wrote that she had no concerns.

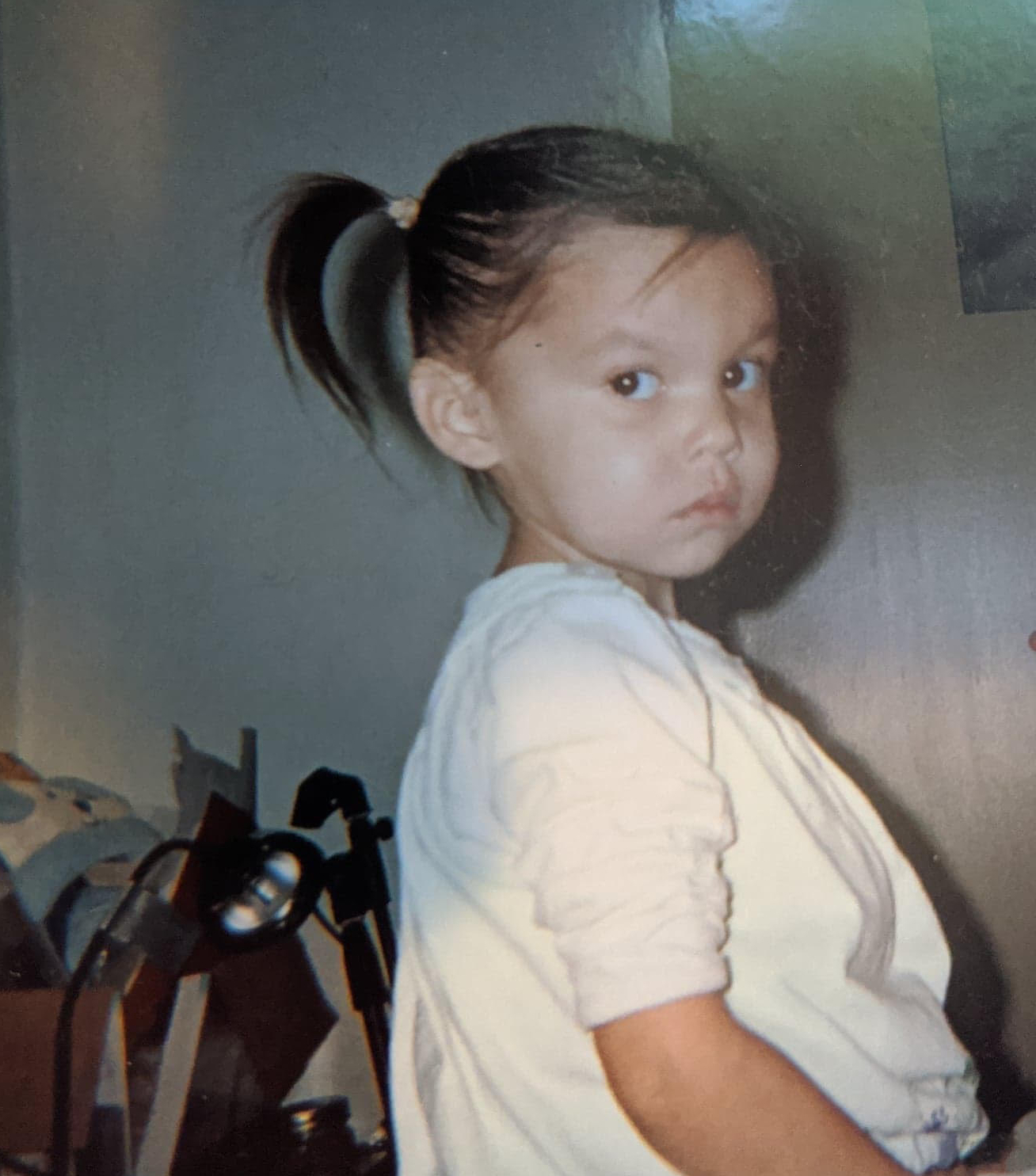

“She’s a bubbly, silly girl who seems to be developing right on target with healthy attachments,” her foster mother wrote in a progress report in February 2013. “She loves playing in snow, stomping around in it when it’s up to her knees, throwing it, digging in it.”

Following an assessment, records show a speech therapist told the foster mother the toddler had a mild delay in using expressive language, but the foster mother noted that didn’t stop Serenity from finding ways to express herself.

She disliked riding in cars, and would kick and scream and need to be pacified with snacks, toys or other distractions. Her favourite song was Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star.

“[She] likes to sing the whole song with me very loudly, the words don’t all come out right, but what she lacks in vocabulary she makes up in volume!” the foster mother wrote.

Exhibits filed at the preliminary hearing show Serenity’s foster mother first reported concerns about moving the little girl in a report she submitted to her foster care agency in March 2013.

She reported that Serenity had come back sick from a visit with the aunt and uncle. Later, the foster mother added, Serenity’s older brother reported Serenity had vomited on a bed during the visit.

“That concerned me as [the aunt] told me there were no issues, and usually you tell a child’s caregiver if the child has a flu,” the foster mother wrote.

Other documents filed show that the foster mother’s sense of unease intensified when she learned, quite suddenly, that Serenity was about to be moved in with the aunt and uncle.

The couple Serenity and her siblings were about to be placed with already had eight children of their own, some of whom were adults, according to a home assessment report completed and approved on April 2, 2013.

“[The aunt] believes that the placement of the children will not be a financial strain on the family at all,” the interviewer wrote. “She believes there is enough money to go around.”

According to the report, during the assessment the aunt told the interviewer she wanted the three children to live with her because they were family, and so they could become more connected to their Cree culture.

“The applicants want to offer the children love, a stable home, teach values, beliefs and know right from wrong,” the report stated.

Two adult children and four school-age children lived with the couple in their eight-bedroom home, but the aunt reported they would be able to care for Serenity and her siblings as well.

None of the children who lived in the home were interviewed separately because of “time constraints,” the report author wrote.

Criminal record checks completed at the time turned up dated and minor records for both the aunt and uncle. The reviewer noted they did not receive a criminal record check for either of the couple’s adult children who lived in the home. A court database search by CBC in January found no criminal records for either of the adult children.

The report states that the aunt told the writer they didn't need any extra support, services or resources. She and her husband did not take orientation or any other training offered by Child and Family Services.

In the assessment, the assessor noted the aunt and uncle were “ready, willing and able to take on the parenting challenges that come along with caring for children under the Kinship Care Order.”

According to records filed in court, Serenity’s foster mother sent an email to a caseworker at 10:22 a.m. on April 13, sharing concerns about the little girl’s second sleepover at the aunt and uncle’s house.

“Serenity came home in a pretty bad mood last night,” she began the email. She said the toddler seemed overtired, threw a tantrum while refusing to eat, and became very upset when her foster mother tried to change her diaper, which wasn’t normal.

“Last night she didn’t sleep well, she was up crying every couple hours, which is something that happened last week as well for two nights after the visit,” she wrote. “But I assumed she was teething or catching a cold. But now it seems like a pattern when she comes back from visits, so I thought I’d mention it.”

The foster mother asked about the date for the guardianship meeting, and for confirmation that Serenity was expected to go for another visit with the aunt and uncle the coming weekend.

“And was also wondering if you could let me know how long you think the transition is going to be, just so we can prepare our family,” she wrote.

At 2:39 p.m. that day, the casework supervisor responded in an email included in the court records, advising the guardianship trial would be held on April 18. She wrote that it looked like the children’s mother had “by all accounts” consented to the move.

“We are planning to facilitate the move to [aunt’s] house for all three children this coming weekend, and we wanted to talk with you further about the plan if you have availability this afternoon,” the casework supervisor wrote.

At 2:54 p.m., Serenity’s foster mother replied.

“Are you kidding me?” she wrote. “Seriously, this child has been in our home, part of our family, for more than two years, since she was a few months old. And she’s almost three, and you think that two, 24-hour visits are enough of a transition? And you think telling me six days in advance of her move is OK? And I was only told six days in advance because I asked. If I had not asked, how much notice would I have gotten? Please do not give me a call, this is a complete shock to me and I think this is the most ridiculous load of bull I’ve ever dealt with in my five years of fostering. And believe me, I’ve seen my share. Wow! That’s about all I have to say about this. Wow!”

At 3:11 p.m., the foster mother sent another email.

“I would like to appeal the decision to move Serenity without a decent amount of transition. I believe it is not in her best interest to be just plunked somewhere she isn’t familiar. Two one-night visits are hardly enough for her. Could someone please send me the necessary paperwork for this please?”

Serenity’s foster mother wasn’t the only one with concerns about the impending move, according to the records. The day before the permanent guardianship hearing was scheduled to take place, several children’s services employees met to discuss “urgent” concerns about the case, according to a single-spaced document, written with bullet points, that appears to serve as minutes of that meeting.

“Meeting was requested by [two workers] — urgent nature — information had to be shared before court this morning,” the notes began.

According to a draft version of the meeting minutes filed with the court, a visitation supervisor claimed she overheard the lawyer appointed to represent the children say: “I hope we are doing the right thing by these kids.”

According to the notes, the supervisor said she followed up with the lawyer about the comment, and the lawyer confirmed her concern was specifically about Serenity and her siblings; the lawyer told her she hadn’t been provided with a file on the children, which she would normally receive in such cases.

The visitation supervisor said the foster parent caring for Serenity’s brother and sister also had “many concerns” about the kids being moved.

“[She] stated that she felt there was a ‘disconnect’ in case-planning and communication between the office, herself, and the foster parents,” the meeting notes read.

“She stated that the foster parents have raised many concerns since the visits with [the aunt] have started, and the department is not doing anything about it.”

According to the minutes, the supervisor said she hadn’t been inside the aunt and uncle’s house, but she’d observed the yard was a mess and was concerned there wouldn’t be enough beds for all the children. The notes also state the supervisor said she took it upon herself to talk to the foster parents about the concerns, and encouraged them to go to court and share their thoughts, though that wasn’t her role.

She acknowledged that though she had been concerned for a time, she didn’t include the foster parents’ worries in her reports and didn’t discuss them with the case supervisor.

She also said Serenity’s mother had told her she didn’t want the kids to move in with the aunt and did not consent to the permanent guardianship order, despite the casework supervisor saying that she had.

The casework supervisor challenged the other woman’s need to know about the kinship placement, because her role was only to supervise the children’s visits with their parents, according to the meeting minutes. She also said if there were concerns, or if the parents had questions, she should have followed up with a caseworker. But she didn’t.

The next morning, April 18, 2013, the court hearing went ahead and a judge granted permanent guardianship of Serenity and her older brother and sister to the province so it could facilitate the placement with the aunt and uncle.

The three kids were moved into the home the next day.

After the move, information about the children appears to have slowed to a trickle.

For a time, the documentation that appears in the court file relates only to notes filed by social workers who picked up the kids for supervised visits with their parents.

According to the documents, the aunt worked at an on-reserve daycare, where the social workers often tried to pick up the children.

Records show that at the time, the relationship between the children’s mother and her aunt had begun to deteriorate.

In May 2013, according to the RCMP summary of the case filed during the preliminary hearing, the aunt told social workers she was limiting the mother’s access to her children because she had been showing up unannounced and was giving the kids too much candy.

In turn, the mother reported that a cousin had discovered some adults in the house were smoking marijuana in the kitchen.

CFS notes from May 23, 2013 contained in the court file state that a social worker who arrived at the daycare to pick up the children was told they were at the aunt’s house. The kids were taken to visit their mother, who was noted to be “neat and clean in her appearance” and did not appear to be under the influence of drugs or alcohol.

“All the children’s needs were met. [Mom] appeared very loving,” the notes read.

A week later, the records show, a different worker went to the daycare and was told the children weren’t there. When the worker drove to the aunt’s house, the aunt said Serenity’s older sister was sick, and she was taking her to the doctor instead of going on the visit.

The social worker collected Serenity and her brother. After arriving with them at the local child welfare office, she realized she had got the time wrong, but called their mother to see if she could come early.

The mother rushed over in a cab, the visit supervisor said in her notes, and swept her two youngest children into a hug.

I miss you, she told them.

She asked if they like being at Kokum’s house (Kokum is the Cree word for grandmother).Is it fun? Her little boy reported that their sister was sick. She had vomited on the bus and then at home, he said.

How’s daycare? the mom asked.

Good, he said.

Do you like it?

Yes.

The mother put Serenity’s hair in a ponytail.

Watch me play, her brother called.

Do you take the school bus? Who with? she asked him.

Serenity pretended to cook.

Cooking looks good. Can I have some? the mother asked as the toddler served her make-believe food.

It tastes good! she said.

The little boy asked for candy, but his mom said lunch first. He bothered Serenity with a toy.

Please don’t scare Serenity, his mother said, scooping her up onto her lap.

Finally, the social worker returned and gave permission for the mother and children to go to Walmart to buy clothes and have lunch. They ate McDonald’s and she bought them new outfits.

When it was time for the children to go, their mother hugged and kissed them.

I love you, she said.

The visitation supervisor drove the kids back to the aunt and uncle’s house, but no one was there. She dropped them off at their daycare instead, according to the records.

Notes from a June 13, 2013 visit state that a worker went to do a pickup at the daycare and was told the children had not been coming there — something their caseworker hadn’t been aware of.

During that visit with their mother at a Dairy Queen, Serenity was fussy but cheered up once the family went out to play in a park.

Six days later, the young mother had her fourth child, a son, fathered by her new boyfriend.

On July 2, 2013, when a different driver arrived at the daycare, the report states the aunt insisted she hadn’t been informed about the visit. The aunt said she would go to the back, where the kids were.

“I assumed she was going to get the kids ready,” the notes read.

When the aunt did not return, the worker asked other staff where she was.

“ … the daycare staff said [aunt] had left out the back door and that those children were not in the daycare but at her residence,” the notes read.

On July 13, 2013, a different social worker went to take the kids for a visit with their parents and other family members.

The gates to the aunt and uncle’s property were locked, so the worker had to call to have the children brought out, according to their report.

In notes filed with the local Child and Family Services office, the writer noted the yard appeared neglected and filled with junk.

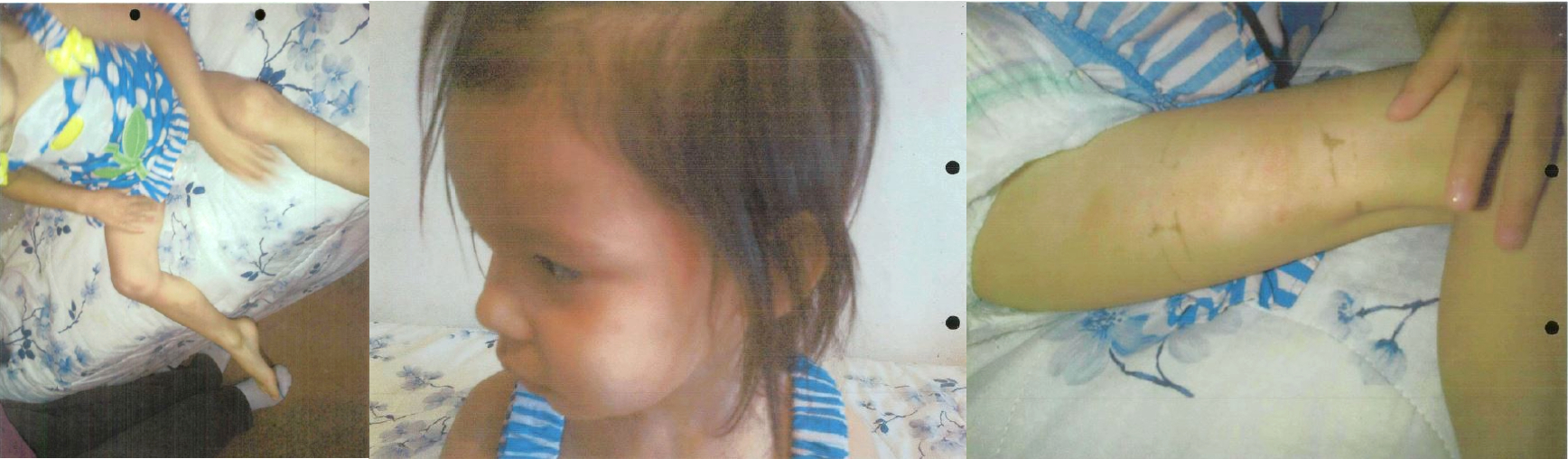

As she buckled the children into their car seats she noticed small bruises and numerous mosquito bites.

“I also noticed a bruise on Serenity’s right cheek, about the size of a silver dollar,” she wrote.

The visit was sweetened with hugs and kisses, and gifts for the children. The older siblings’ dad played with the kids and their mother served them lunch, according to notes from the day.

A birthday cake was served and the children blew out candles. Treat bags were handed out.

The writer noted that as various relatives helped clean up the party room at the social agency, Serenity’s mother was changing her daughter’s Pamper.

“She showed me some sores on the inside of Serenity’s thighs about midway between her knees and body,” the note reads. “I also noticed a rash of sores on the upper part of Serenity’s buttocks. [Mom] told me she had taken pictures of the sores on the children before.”

When the children were taken back to the aunt and uncle’s home, the gates were again locked, according to the notes. The writer said an older man walked up and talked to her about the fence.

“I looked at the fence and saw that it was pieced together with mismatched pieces of wood and metal work,” she wrote.

The worker noted in her file that she reported the bruises, bites and sores to the children’s caseworker.

According to CFS records filed with the courts, caseworkers observed that the relationship between Serenity’s mother and her aunt had become further strained because the mother expected to get her children back after they were placed with the aunt.

The mother disputes that, and said recently she was trying to work with her aunt in hopes of one day regaining custody. She said that effort ended when she began to believe her children were being mistreated.

Concerns about the children’s welfare led to an official investigation by the caseworkers involved with the family on July 15, 2013.

According to records, the aunt was called and advised that there would be a visit to her home that day.

A report from the visit states that when social workers arrived at the aunt’s home, Serenity was sitting on the couch with an older cousin. Her sister and brother were dancing.

“They were well-dressed and they all appeared to be in a good mood,” the social worker wrote.

The aunt told the workers Serenity had bruised her face by falling into a rocking chair while dancing. The aunt claimed the rash was because the little girl was defecating several times a day. The social workers told her she needed to take Serenity to a doctor. They asked about the children’s eating habits.

The social workers wrote that a large pot of soup was cooking on the stove, and reported that the aunt said the children loved her cooking.

During the visit, the caseworker forged ahead with plans to get the aunt and uncle private custody of the children, and explained the necessary paperwork to the aunt. She told the aunt to take the children to the doctor.

But Serenity’s mother was still concerned, and told anyone who would listen.

Records show she called her MLA, Verlyn Olson, who was serving as minister of agriculture at the time. His constituency assistant emailed the Central Alberta Child and Family Services office on July 17, 2013, and asked them to look into an emergency request made by Serenity’s mother.

“She says that she is very concerned about the welfare of her children, and would like them placed in a different foster home so they are safe,” the assistant wrote. “[The mother] maintains that she has gone to her social worker several times over the past month, and the worker does not listen.”

“ … [the mother] is not certain that anyone is going to listen to her before her children get hurt more. [The mother] says that the children are getting very thin, and have bruises, and health concerns.”

Other records filed show the request triggered an email chain among central Alberta Child and Family Services staff, which suggests at least one provincial government minister was made aware of the complaint.

“Apparently [mother] has scheduled visits with the children that she often misses, but will show up unannounced to visit the children. The family is working on establishing boundaries, which makes [mother] very angry,” a program relations specialist wrote in an email forwarded to the regional manager of public relations.

That manager in turn forwarded the complaint further up the chain, adding a request.

“Can you make contact with [the mother] to follow up and report back on the outcome? We will then report to the minister’s office.”

On July 18, 2013, the young mother’s new baby was seized under an apprehension order, according to CFS documents.

The mother said the baby, about a month old, was taken away because social workers found a bag of marijuana when they searched her house.

“They took [the baby] away from me for having an ounce of weed,” she said. “And she made me and [her partner] go to rehab.”

According to notes dated that same day and later filed with the court, the mother went to her social worker in tears, saying her older children were being mistreated.

“She said that the children were starving, and that they had to get up through the night to steal fruit out of the fridge,” a caseworker wrote in a report about the meeting, adding that she tried to reassure the mother that her children looked fine.

“This writer told [the mother] that when she saw them at [the aunt’s] the day before they appeared happy and didn’t look any thinner,” she wrote. She said Serenity looked tired, and the aunt had been instructed to take her to the doctor.

The mother cried throughout the meeting, according to the notes.

She told the social worker she knew she would never get her children back. “I thought this was going to be the best thing for them,” she said, according to the notes. “But now I just want them in foster care where they are safe and not hungry.”

The caseworker wrote: “This writer assured [the mother] that her concerns were heard and that we would make sure that they were safe and not hungry.”

The next day, Serenity’s mother met with caseworkers again about her complaint to Olson’s office. She said the social worker hadn’t addressed her concerns, and that the children had reported the house was dirty, they stayed in their rooms all day, and that the older children hit them when they didn’t listen, according to the court records.

The social workers asked if there was any way the mother could change her relationship with her aunt. The mother again said she was worried about her children, notes from the meeting state.

She and her partner were then trying to get their infant son returned to them. The couple started the rehab program, but the mother said in a recent interview they decided to move to British Columbia, where her partner’s family lives, and get a social worker there who might be more willing to work with them.

She said they arrived in British Columbia and she worked with a social worker there, who helped the couple regain custody of their infant son.

“She returned my son to me without having to go to rehab for weed,” the mother told CBC. “She told me I seemed like a good person.”

WATCH THE FULL DOCUMENTARY

Back in Alberta, caseworkers found the aunt’s explanations for the children’s injuries were plausible, according to the court documents.

Still, the records state that on July 19, 2013, the aunt was directed to take the children to the doctor for checkups. Later documents show that when a caseworker followed up about this, the aunt said she was “too busy” to go.

After prodding by a caseworker, she finally took the kids to the doctor on July 24, 2013, according to the CFS files.

While there, the doctor noted that Serenity had lost more than two pounds since December, when she’d been in foster care. He said the older sister was also underweight.

The doctor made referrals for Serenity to see a pediatrician, and for blood work. Records show the pediatrician who saw her in October 2013 asked the aunt to bring Serenity back for a follow-up appointment in three months.

There’s no record of that happening, according to an RCMP review of Serenity’s medical history.

Because of the concerns about Serenity’s condition, a specialized investigator was assigned to complete an assessment, according to an internal review later undertaken by Alberta Human Services.

During a visit to the home on July 26, 2013, caseworkers reported observing the children eating breakfast.

In a photograph apparently taken that day that was later filed with the court, Serenity sat at a table between her older siblings, wearing a yellow T-shirt and eating pancakes off a green plastic plate.

The investigator’s review included interviews with the children and their caregivers. The older children reportedly said they “loved” living in the home, while Serenity was “quiet during her interview and did not engage in any direct conversation.”

“Those pictures from that day haunt my memory, because whenever I pull them out I can see she’s just not happy.” — Serenity's mother.

The review states the aunt told the investigator she understood she would have to follow up on medical appointments. She said the children were active and had accidents, but she had adjusted her home so more accidents wouldn’t happen. She said she was aware of the children’s desire to eat more.

“[The aunt] was clear that no neglect occurred in her home,” the review read.

The investigator also spoke to the doctor who had seen the children, and was told Serenity had been referred to a pediatric specialist in Leduc. CFS confirmed that Serenity was taken to that appointment.

The investigator concluded that the allegations of physical abuse and neglect were not substantiated, according to the review.

On Oct. 10, 2013, a caseworker received an email from a sender whose identity was redacted in the court documents obtained by CBC. The sender raised concern that the caseworker planned to take permanent custody of Serenity’s mother’s new baby and place him with the same kinship caregivers.

The sender noted there were “grave concerns” about the environment and level of care in the home, and listed hygiene problems, scabies and lice, overcrowding with 14 people living in the house, an unsafe yard filled with junk, family violence, a number of people smoking marijuana, and an allegation that the aunt and uncle had taken the children “just for the money.”

“[Name redacted] claims that these concerns have been reported to the Alberta Social Services office and nothing is done,” the email said.

“What is the process of reporting these concerns through the proper channels if this has not been done?”

According to CFS records, on Oct. 11, 2013, Serenity’s mother told a caseworker she was aware of the plan to grant the aunt and uncle private guardianship of her children, and did not plan to contest it.

When the caseworker drafted an order recommending the aunt and uncle be granted private guardianship, she wrote that Serenity had been declared “healthy overall.”

In a recent interview, Serenity’s mother said the last time she saw her three oldest children together was during a visit to celebrate Halloween in October 2013. She said her two older kids seemed OK, but she was worried about Serenity.

“Those pictures from that day haunt my memory, because whenever I pull them out I can see she’s just not happy,” the mother said. “I wish maybe if I would have gone to the police that day maybe something would have happened. But I didn’t.”

After the couple were granted private guardianship on Oct. 24, 2013, the document trail dried up. Once the order was granted, Child and Family Services no longer had lawful authority to monitor the family.

On Feb. 4, 2014, records show the provincial government closed its files on all three children.

That summer, on June 23, 2014, security guards at West Edmonton Mall noticed two small children walking unattended through the mall.

The guards followed the kids, a boy and a girl they later reported as looking “malnourished,” according to an internal review of Serenity’s case by the province that was completed in 2015 and ultimately filed with the court.

The children left the mall on their own. Outside, they climbed into a car. The guards took down the licence plate and filed a report with Edmonton police.

The car belonged to Serenity’s kinship care provider, according to the review. The complaint was sent to the local RCMP. A police officer went to the home and asked the aunt about the children’s health.

She reportedly told the officer the children were so small because they had tapeworms. She told the officer they were on medication, and were going to see a specialist about it. No documentation was provided.

The matter was referred to the on-reserve child and family services office for followup.

In an email on July 7, 2014, one worker was asked to contact the aunt and ask which doctor was treating the children, so they could check the tapeworm story.

“If we can confirm what [aunt] stated about children having tapeworms, and that she is following a treatment plan, there would be no reason to pursue this any further,” the email said. The court files included no documentation to suggest anyone followed through with that investigation.

As the mother and her partner built a new life in British Columbia, she continued to long for her three children in Alberta.

“I was so depressed that I didn't have my three kids all the time,” she said. “Every night I would literally put my babies to sleep, and then I would go cry myself to sleep because I was constantly, always, worried.”

“I never put pictures of them up because it would make me sad.”

The tire swing in the aunt’s yard hung suspended by three chains from its wooden frame.

The grass below was worn away in a near-perfect circle. Behind the swing, green bushes and a fenced paddock were visible in the background.

A dog lazed in the grass near the edge of the photograph, which was taken by police who documented the scene.

Three people initially claimed they saw Serenity fall from the swing on Sept. 18, 2014, including her older half-sister, who was seven, and her half-brother, who was six, according to a record of the RCMP investigation into the case that was later filed as an exhibit at the preliminary hearing.

Over time, records show stories about what exactly happened changed from witness to witness, and interview to interview. Generally, police were told the children were playing in the yard when Serenity fell off the swing.

It took nearly two years for the report from the medical examiner to be completed. When it was, pathologist Dr. Bernard Bannach concluded that complications from blunt cranial trauma — a head injury — caused the little girl’s death. He determined it was possible the injuries were caused by a fall from a swing.

“As the exact circumstances leading to the head injury cannot be determined with a reasonable degree of certainty, the medical statistical manner of death remains undetermined,” Bannach said, according to the RCMP report.

Witness accounts of the afternoon Serenity fell from the swing vary depending on who was speaking, according to the police records that were later filed in court.

Did Serenity ever regain consciousness? Did she speak? Did she get up and walk back into the house? Did someone throw water on her face? Why had her clothes been changed? Was she left lying on a couch, or put in a corner? Did she squeeze someone’s hands on the ride to the hospital?

Whatever happened, it may not have made much difference to the outcome. After arriving at the nearest central Alberta hospital, medical records show Serenity was flown by STARS air ambulance to the Stollery Children’s Hospital in Edmonton.

In followup meetings with the RCMP, Bannach explained that the prognosis for surviving the type of head injury Serenity suffered decreases sharply after 30 minutes, according to the police records.

Given the distance from her aunt’s home to the closest hospital, it wouldn’t have been possible for Serenity to be seen by a neurosurgeon within that 30-minute window, Bannach reportedly said.

Medical records show the doctors and nurses who worked to save Serenity's life were horrified by her overall condition, and suspicious.

“She was extraordinarily emaciated,” Dr. Michele Harvey-Blankenship, a pediatrician with the Child and Adolescent Protection Centre, wrote in an October 2014 report she sent to the child and family services office on the reserve.

“No subcutaneous fat was evident. Her ribs were clearly visible and her sacrum was covered only by skin. Her buttocks was wasted.”

Serenity had lesions all over her body, which were photographed.

“She had bruising on her forehead, around her lips, on her mons pubis, around her anus, and multiple bruises on her hands,” Harvey-Blankenship wrote.

She said Serenity had burst blood vessels across her chest and on her back.

“There were linear patterned bruises across her back, buttocks and legs. There were multiple scabs and abrasions across her hands,” the pediatrician noted.

The doctor said X-rays showed previous injuries to one of Serenity’s pinkie fingers, and to the second toe on her left foot.

At the time, Harvey-Blankenship agreed the fall from the tire swing could have caused the massive subdural hemorrhage that ultimately killed Serenity.

“This explanation, though, did not account for her severe emaciation and profound malnutrition, nor did it explain the extent of the petechiae, bruising, abrasions, scabs, and patterned bruising,” Harvey-Blankenship wrote.

“The severe emaciation, malnutrition, and skin findings likely contributed to the severity of her presentation and may even have contributed to the acute event.”

Bannach disagreed. He told police that Serenity’s body composition would not have had an effect on her head injury, according to police records.

In an interview, Serenity’s mother said her daughter had been in the hospital for two days before she was told. A cousin called when she was feeding her baby breakfast.

“She said, ‘I have to tell you something, but I don't want you to freak out because I don't know if it's true or not,’” the mother recalled.

“And she's like, ‘I heard Serenity’s on life support.’”

The mother said she hung up the phone.

“I frickin’ looked at everybody in the kitchen, and I screamed. And I ran outside and my legs didn’t work, so I just sat on the ground.”

She said her cousin called back to say she didn’t know if the news was true or not.

“And in my heart, I knew it was,” she said. “And I just told her that. I said, ‘It’s true, I know it's true. She's there, I know it.’”

Her cousin called the uncle, the mother said, and was told it wasn’t true, that Serenity wasn’t in the hospital. The mother didn’t believe that.

Scrambling, she reached out to child welfare, but said staff told her they weren’t involved in the case. She insisted they check.

A half hour later, she said, the child and family services office on the reserve reached out to confirm her daughter was in hospital.

She was told the agency would handle the case, that provincial child and family services wouldn’t be involved.

The mother said she tried to get on a flight, but her ID had expired. She found someone to drive her to Edmonton.

“I had to drive the longest drive of my life to the hospital to say goodbye to my kid,” she said.

Records of Serenity’s weight in September 2014 vary widely.

The doctor who delivered her in June 2010 described her as a “healthy, normal baby” who was born prematurely and weighed 5.8 pounds at birth, according to a medical history compiled by the RCMP in their investigation report filed in court.

According to Harvey-Blankenship’s report, Serenity gained weight well from the time she was born until her first birthday.

When she was about 26 months old, she dropped below the third percentile of weight, meaning she weighed less than 97 out of 100 children her age.

She started to make gains again from age three to about three-and-a-half. Shortly after she turned four, however, “she had very clearly plummeted in her weight to well below the third percentile,” Harvey-Blankenship wrote.

A social work record for the day she was admitted to hospital said she weighed less than 20 pounds.

A handful of other charts recorded her weight as 22 pounds. Harvey-Blankenship’s report states that Serenity’s weight was estimated at between 19 and 22 pounds when she was admitted to hospital.

When she was weighed during her autopsy, Bannach recorded her weight at 25 pounds. He said that being on IV fluid while hospitalized could have caused her to “lose a pound or two.”

According to the RCMP report, Bannach agreed during his 2016 interviews with RCMP that Serenity was malnourished, which he said could have been caused by not eating enough or not being provided with enough food, or by an undiagnosed medical condition.

In her report, Harvey-Blankenship said testing found “a notable mixed amino acid deficiency in keeping with insufficient protein intake, or increased protein metabolism or excretion.” The doctor noted her kidney and liver functions were normal, and that all previous screens — including as a newborn — had been normal.

Injuries near Serenity’s anus and genitals were noted on medical reports. One record noted that the child’s hymen may be missing.

But according to the RCMP’s investigative file, Harvey-Blankenship found that the bruises around Serenity’s vagina and anus were not consistent with sexual assault, and Bannach found that her hymen was intact.

“Investigators do not believe there is evidence to suggest a sexual assault took place,” RCMP wrote in a summary of their findings.

Police decided to interview Serenity’s siblings. According to RCMP files, when officers and social workers arrived at the home on Sept. 19, 2014, to pick up the children, the gate to the property was locked.

It took 75 minutes for the two children to come outside. The province’s internal review notes the family displayed “limited co-operation.”

When the siblings arrived at the Zebra Centre for Child Protection in Edmonton, records note that the six-year-old boy was “roughly the size of a four-year-old,” and that his seven-year-old sister was “thin and pale.”

According to transcripts in the court file of the first interview with investigators on Sept. 19, Serenity’s sister told police Serenity was sometimes hit with sticks or clothes hangers while in the home.

She also alleged Serenity was punched in the face, causing a nosebleed. She told police her mother’s aunt had told her that if she lied she would have to stay in Edmonton. Her younger brother initially told police there was no hitting in the house.

The aunt was also interviewed by police on Sept. 19. She told officers that Serenity bruised easily and had always been skinny, according to an RCMP summary of the investigation.

She claimed the family tried to help the little girl gain weight, and took her to a doctor, a claim her daughter repeated, according to the summary.

Police records note the aunt told investigators the children were disciplined with time outs. She reportedly told police she didn’t call an ambulance for Serenity after the fall because it would have taken too long to arrive, and said she had “no reason” for changing the little girl’s clothes before taking her to the hospital.

Other members of the family who lived in the home, both adults and children, were interviewed and reiterated the story about the fall from the swing.

Police files show multiple children, including Serenity’s siblings, said the four-year-old’s other injuries had been self-inflicted.

On Sept. 20, 2014, social workers secured an apprehension order to take custody of Serenity and her siblings.

Meanwhile, records show that doctors at the hospital were urgently trying to reach the aunt and uncle. Serenity’s condition was deteriorating and they needed to make a decision about a do-not-resuscitate order.

During a phone call the next day, Serenity’s aunt told social workers she and her husband would attend a medical meeting later that day, according to an affidavit filed in 2015 by one of the caseworkers involved with the family. The caseworker stated the aunt and uncle never showed up for the meeting.

Serenity’s mother said she can’t recall whether she finally arrived in Edmonton on Sept. 21 or the following day.

“I walked into the room and, you know, I looked at her, and it did not look like her,” she said. “It just did not look like my Serenity at all. She was so, so starved to death. She just looked like a skeleton with skin on her, and she didn't even look like her. She didn't barely even have a nose because her nose was so small.”

Moments later, social workers showed up with Serenity’s older brother and sister.

“I turned around and I saw them,” she said, “and I fell to my knees, because I was so sad about Serenity. But I was so thankful that they were alive. I didn’t know what to do at that moment. Do I sit here and cry? Or do I sit here and hug these two kids and tell them everything is going to be all right? I didn’t really have time to cry because there were two kids right there looking at me.”

On Sept. 23, Serenity’s siblings were again interviewed by police. This time, according to police records, they both talked about physical abuse occurring in the home.

They said the adult who punched Serenity in the face did so because she was stealing food. Her brother said Serenity was hit with hangers and a belt.

On Sept. 25, the aunt and uncle appeared in family court to address the custody issue. According to the caseworker affidavit, the aunt said Serenity had been “fine” when she had last seen her, while the little girl was being admitted to the hospital.

The uncle reportedly said he “didn’t know anything” because he had been living in a shack behind the house, rather than inside.

The couple was questioned about Serenity’s bruises, which the aunt attributed to the fall from the swing. Asked about Serenity’s weight, the couple did not respond, the caseworker alleged.

After all of the mother’s efforts to get Serenity back, a judge finally awarded her custody.

“He granted me custody of Serenity back,” the mother said, “so that I was the one that had to go and I was the one who had to say, ‘OK, it's time for her to go now.’ So that's the only time [they] gave me custody back, was to pull her life-support cord. So none of them had to do it.”

The aunt and uncle, along with one of their daughters and an elder and spiritual adviser, went to Serenity’s room in the hospital to pay their last respects, according to the caseworker’s affidavit.

“Look how small she got,” the aunt reportedly said. The uncle remained silent while their daughter texted on her cellphone. According to the affidavit, the elder said in Cree, “Just let them kill her,” and left the room.

Serenity’s father, who was in prison at the time, was brought to the hospital to say goodbye to his daughter, records show.

On Sept. 27, 2014, Serenity’s medical team told her mother it was time. Many people were gathered in the room. Serenity’s mother sat at the foot of the bed.

“I could not see my daughter take her last breath of air,” she said. “I just could not do that. I could not see her not breathe anymore, so I had to sit at the end of her bed on my knees, and I just held her feet.”

She said it took Serenity about five minutes to die.

“It was the worst feeling, probably the worst day of my whole life,” she said. But just outside Serenity’s room, her surviving siblings were waiting.

“How do you deal with that, and then at the same time I have to be so strong for other little human beings, because now they're looking at you for that? You have to teach them to be strong. And that's what I had to do. I had to teach them how to deal with things, because they had been through so much.”

Not long after Serenity died, records show, her brother and sister were referred for counselling to deal with grief and trauma. They also met with a dietitian and pediatrician.

According to a caseworker’s affidavit, in the 10 days after the siblings were removed from their kinship care home and placed in the custody of the on-reserve child and family services agency, the boy gained more than four pounds, and his sister gained about six pounds.

“The dietitian advised caseworker to allow children to consume food at their pace, as this is what is referred to as ‘catch-up weight,’” the worker wrote.

Though police opened the case shortly after Serenity arrived in hospital, it was years before they released findings. Records show they conducted interviews and took pictures at the property.

The RCMP’s major crimes and forensic identification units were both updated on the case but did not attend the scene, according to police files.

In April 2015, police contacted Child and Family Services about accessing records, but were told a procurement order would be needed, according to the RCMP summary of the investigation.

“At that time, a decision was made to await the medical examiner’s report to determine the exact offence being investigated,” the report said.

"There are no specific features identified at neuropathological examination to indicate the nature of the blunt trauma that occurred to cause the injuries identified." — Calgary neuropathologist Dr. Leslie Hamilton

Once police received confirmation the medical examiner’s report was on its way, they tried to access Child and Family Services records, filing a request with one of the agency’s central Alberta offices on July 19, 2016.

The final report from the medical examiner was completed on Sept. 9, 2016, after Bannach received the results of an examination of Serenity's brain by Calgary neuropathologist Dr. Leslie Hamilton.

Hamilton confirmed that "blunt head trauma and its complications" caused the death, but found no evidence to suggest what led to the trauma, whether a fall from a swing or otherwise.

"There are no specific features identified at neuropathological examination to indicate the nature of the blunt trauma that occurred to cause the injuries identified," Hamilton wrote.

While waiting for the medical examiner’s report, police followed up with Serenity’s mother and siblings about further disclosures of abuse. Records show they also investigated the possibility that someone in the home had struck Serenity in the head with an object.

That theory was determined to be unfounded by police, and they concluded that there were “reasonable grounds” to believe Serenity died because of the fall off the swing. At a September meeting with Crown prosecutors, a decision was made not to pursue homicide charges, according to a summary of the investigation.

During Bannach’s discussions with police in 2016, files show he told investigators he did not think there was any evidence that Serenity died from being beaten.

On Oct. 12, 2016, a Child and Family Services officer told RCMP they would have to file a request for Serenity’s records through the on-reserve children’s services office.

Alberta’s Office of the Child and Youth Advocate was already conducting its own review, and on Nov. 15, 2016, released a report on Serenity’s death, identifying her only as “Marie.”

In his report, advocate Del Graff cited the death of a malnourished four-year-old and called for more thorough assessments of kinship placements. He also called on the province to strengthen safeguards for children in such situations.

Media reported extensively on Graff’s report.

After months of attempting to track down and access Serenity’s intervention records, RCMP were finally granted access on Nov. 22, 2016. But “due to RCMP technology,” they weren’t able to open the documents to view them until Dec. 6, 2016, according to a review of the case.

Around the same time, Serenity’s mother went to the media. For the first time, photographs of Serenity — the once happy, chubby toddler — were published, making headlines across the country.

The photographs of a healthy, active toddler were later published side-by-side with pictures of the four-year-old lying bruised and emaciated in a hospital bed, attached to a tangle of tubes and wires.

The story sparked shock and outrage. Within days, a ministerial panel was struck to look at the child intervention system.

The panel later came up with dozens of recommendations aimed at strengthening Alberta’s child intervention system. Danielle Larivee, the children’s services minister at the time, promised to implement all of the recommendations.

On Dec. 12, 2016, an email from RCMP major crimes Insp. Derek Williams outlined what police had learned so far in their review of 7,400 pages of Child and Family Services records.

Williams noted he expected more back-and-forth between police and the local Crown as prosecutors conducted a review of a possible charge of failure to provide the necessaries of life.

Soon after, then-premier Rachel Notley split the human services department in two, creating one branch known as community and social services and another as children’s services. She cited Serenity’s case as one of the motivations behind the change.

On Oct. 5, 2017, more than three years after Serenity’s death, the RCMP laid a charge against the aunt and uncle for failure to provide the necessaries of life.

"I've been waiting to hear that for three years, so it really hit home, really hit my heart,” Serenity’s mother said after the charge was announced. “It was a really emotional day.”

Her sense of relief was short-lived.

A preliminary hearing began in February 2019. In August of that year, Crown prosecutor Brandy Shaw filed a stay of proceedings.

"The charges were stayed following review of the evidence at the preliminary inquiry and a determination that we no longer had a reasonable likelihood of conviction," Shaw told CBC in an email.

In a statement, Eric Tolppanen, assistant deputy minister of the Alberta Crown Prosecution Service, also said there was no longer any reasonable likelihood of conviction. He noted the Crown has one year to potentially reinstate the charge and declined further comment.

That window closes on Aug. 13, 2020; a check with court staff on May 28 confirmed the charge remains stayed, and that nothing further is booked for the case.

In an interview with CBC after the charge was stayed, Serenity’s caregivers denied that the little girl had been abused. They claimed their lives had become a nightmare after the allegations went public.

"It hurts to be accused of something you didn't even do," the aunt said, tears running down her face. "It was an accidental death. A tragic accident that happened. They turn around and blame us like we did something to her. We did nothing but protect them and help them."

This month, CBC reached out through the couple’s lawyer, Robert Lee, and posed a number of questions about Serenity’s care and the child’s physical condition at the time of her death.

In an emailed response, the aunt said that had the couple known about Serenity and her siblings’ “high needs,” they would not have taken the children in, and argued that the province’s child welfare system misled and coerced them. She said they wanted to help Serenity and her siblings because of the systemic racism she says Indigenous people face in Alberta’s child welfare system.

Looking back at the stories written at the time of the arrest, Serenity’s mother said she feels like she was led on, that her daughter’s case was never properly investigated, and that the prosecution wasn’t pursued in good faith.

“They were just doing this so it looked somehow like they were doing a proper investigation,” she said. “But they didn’t. Not at all.”

Serenity’s death also triggered a series of civil legal actions: her mother filed a lawsuit against the kinship care guardians and other members of their family, their First Nation, the province, and two social agencies who had involvement with the family. All of the defendants have filed statements of defence, denying the claims made against them.

In turn, the aunt and uncle have filed claims against members of the media — including CBC, Corus Inc., and former Edmonton Journal columnist Paula Simons, now a Canadian senator.

The civil actions are all ongoing, and none of the allegations made in the claims have been proven in court.

Serenity was among 33 children and young adults to die while receiving intervention services from the province between April 1, 2014, and March 31, 2015.

According to the data the province publishes, 20 of those children were Indigenous.

Nearly every year, Indigenous youth and children account for more than half the deaths of young people who die while receiving intervention services from the province, though Indigenous people make up 6.5 per cent of Alberta’s total population, according to 2016 census data.

Dozens more children and youth have died in the years since:

- 2015-16: 22

- 2016-17: 26

- 2017-18: 33

- 2018-19: 33

- 2019-20: 33

The province tracks deaths according to its fiscal year, April 1 through March 31. The most recent numbers available for the current fiscal year show that there were two deaths between April 1 and April 30.

In Alberta, the province holds a fatality inquiry when someone dies while in the custody of the government, whether it be a prisoner or a child in care. Provincial court judges who preside over the hearings cannot assign blame, but can make recommendations aimed at preventing such deaths in the future.

The fatality inquiry that will examine the circumstances of Serenity’s death has yet to be scheduled. It’s on a list of cases awaiting court dates, pending the resolution of investigations and criminal matters.

In the meantime, the way the province manages and supports kinship care providers remains under review.

In Child and Youth Advocate Del Graff’s 2016 review of Serenity’s death, he flagged a number of concerns with the province’s kinship care program, including a lack of mandatory training, as well as the receipt of less support and resources than non-familial foster parents.

He also noted that the supports need to be culturally relevant.

“In particular, Aboriginal kinship caregivers may be resistant to getting involved with Child Intervention Services due to historical experiences of oppressive and culturally inappropriate services,” Graff wrote.

Better support for kinship caregivers was among the final recommendations of the intervention panel that was struck by the then-NDP government after Serenity’s death.

“... Serenity’s death is a tragedy that informs many of the changes made in the way Children’s Services works. Our priority remains keeping children with their families whenever safely possible.” — UCP press secretary Lauren Armstrong.

When the United Conservative Party replaced the NDP, Rebecca Schulz was appointed minister of Children’s Services. In an interview in January, Schulz said many of the recommendations made by the intervention panel were already in place. But others — including a recommendation to increase training and funding for kinship caregivers — were still under consideration.

Part of the holdup, Schulz said, was that the province has outstanding questions about new federal rules that could upend the structure of child welfare oversight across the country.

The new rules recognize inherent First Nations, Métis and Inuit jurisdiction over Indigenous children who are in care, and outline requirements that child intervention service providers must meet when working on cases involving Indigenous children.

No implementation plan — or budget details — have been released to provinces, which has left Alberta in an uncertain place.

Schulz said she was pleased that recent numbers show a higher proportion of children in the system are being placed in kinship care, with such placements up 17 per cent over the same time frame from the previous year. She said she thinks that is a positive development, in line with the panel’s findings.

In a followup query about policy changes in May, Schulz’s press secretary Lauren Armstrong said the focus in recent months has been on ensuring vulnerable children are still receiving services during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“This has also been the case for many First Nations as well as the federal government, so there have been no recent updates regarding federal laws relating to Indigenous children in care,” Armstrong said in an email.

“That said, Serenity’s death is a tragedy that informs many of the changes made in the way Children’s Services works. Our priority remains keeping children with their families whenever safely possible.”

In the months after her daughter died, the young mother finally regained custody of her two older children.

After Serenity’s funeral, the siblings began to spend more time with their family, and in December 2014 both were placed with their mother at her home in British Columbia.

The mother had made a new life for herself on the West Coast, where she lived with her partner and younger children.

An inspection of the home found the only deficiencies were the need for an extra fire extinguisher and a carbon-monoxide detector.

On a Wednesday in February, Serenity’s mother was at home on Vancouver Island with her son, who had a cold. She lives with her five children, ages three to 12. Her oldest daughter and son are in school, and doing well.

She said they know they can talk to her when they’re having a hard time dealing with the past.

“Is there a day that goes by that they don’t think about their sister? No,” she said.

But she tells them Serenity would want them to be happy.

She is engaged to the father of her three youngest children. He works for a fishery, and she’s halfway through a culinary arts program. Her four oldest children go to school. The youngest will start an early learning program in September.

She said she’s honest with her children when they ask about what happened to Serenity, or their former guardians. She said she tells them her aunt and uncle likely won’t face any legal consequences.

For a while, when the police investigation and court case were active, Serenity’s mother made frequent trips to Alberta, fighting for her daughter’s voice to be heard. But she worried she was spending too much time away from her other children.

She sat them down and asked what they wanted. She said they told her to keep fighting for Serenity.

After everything her family has been through, she said she has no faith in the system. Despite her doubts that Serenity and her older siblings will ever get justice, she said her children — and other people’s children who have been harmed — motivate her to keep calling, asking questions, posting online, and telling her daughter’s story.

“I've felt there's times where I felt like maybe I should just let things go,” she said. “Maybe I should just stop, because it's not going to get anywhere. But then in the back of my mind I hear those words — don't give up yet. And so I'm not.

“At the end of the day, at the end of my life, do I want to sit there and go, ‘What if?’ Or do I want to sit there and go, ‘Man, I tried.’ So I'd rather die knowing that I tried to get them justice. So that's my motivation. My three kids, they deserve justice. Will they get it? I don't know. I can’t say that. I have no hope in the Alberta justice system.”

After she took Serenity off life support, she donated her daughter’s heart tissue. She said she was told that Serenity was the donor for a little boy. She sometimes thinks about how that child is probably about to start kindergarten.

“She was able to save him,” she said. “That makes me happy.”

A traditional Cree wake and ceremony was held for Serenity in her home community, then her remains were cremated.

In the months after her daughter’s death, the mother was too afraid to keep Serenity’s ashes around. Her own mother held onto them, until she was ready. Now Serenity is never far from her: the ashes are enclosed in a statue of a beautiful white angel. She keeps it in her bedroom.

Until recently, she had put off hanging photographs of Serenity in her home. It was hard, she said, for the kids to look at the photos. It made them sad. But she had committed to making sure her kids know the truth about their sister, and as a family they talk about what happened. Over the past few weeks, she started hanging the photographs.

“It’s OK,” she said. “They can walk by her picture and they can smile.”

Correction: This story previously stated that the kinship caregivers had permanent guardianship of Serenity and her siblings. In fact, a judge awarded guardianship to the province, which in turn placed the children in the kinship guardians' home.