October 28, 2018

A gunshot broke the quiet in the jungle hamlet of Victoria Gracia. There was a commotion outside a cluster of modest wooden shacks on the main dirt road. Then two more gunshots rang out, and 81-year-old Olivia Arevalo Lomas, one of the most renowned shamans in the Peruvian Amazon, lay dead on the ground.

While the locals in Victoria Gracia don’t trust the authorities, someone called them. After a while, the police from the nearby city of Pucallpa were there, marking the scene, collecting evidence, taking names. Grieving villagers stood by, fuming as Arevalo’s body lay in the dirt for hours.

Before the authorities had even started their work, the villagers had fingered a suspect: a British Columbia man named Sebastian Woodroffe.

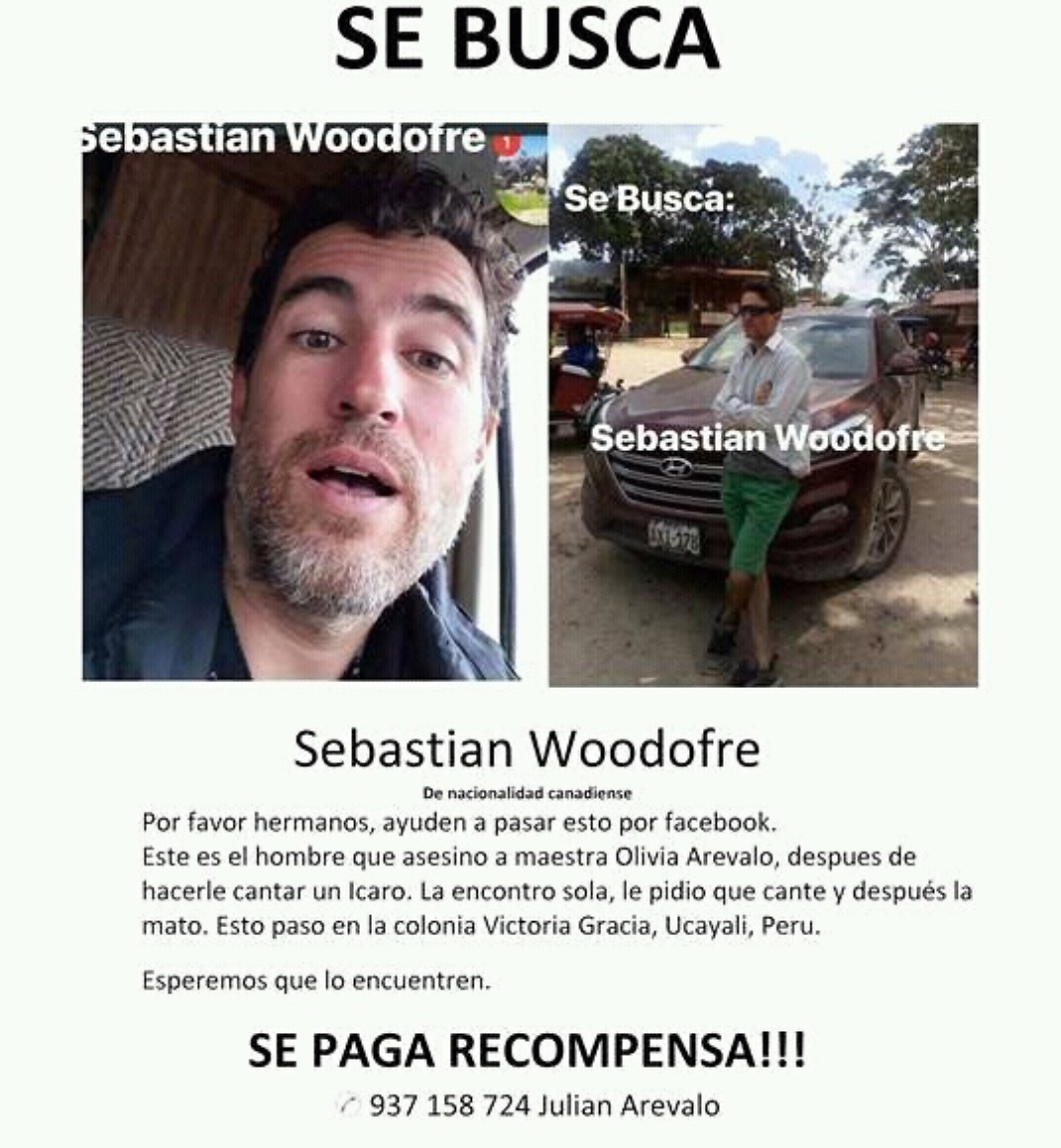

Soon after the shooting on April 19, 2018, a homemade poster was circulated online, with the words "SE BUSCA" — Spanish for "wanted" — in bold caps at the top of the page. Below were two photos of a gringo male with dark hair and stubble. He was identified as "Sebastian Woodofre [sic], De nacionalidad canadiense."

"Please brothers, help pass this on facebook," the message read. "This is the man who killed our teacher Olivia Arevalo, after making her sing an Icaro. He found her alone, asked her to sing and then killed her. This happened in the Colony of Victoria Gracia, Ucayali, Peru."

In South American Indigenous culture, an icaro is a healing chant. Sung by a curandero, or shaman, it is said the icaro channels medicinal spirits.

"Let's hope they find him," the poster said, offering the familiar incentive: "REWARD!!!"

But the poster was misleading. The suspect wasn't on the run. According to local authorities, the poster was a ruse meant to distract police from the grisly fact that Woodroffe was already dead — lynched by a mob just minutes after Arevalo's killing.

We know this because a cellphone camera was a witness. And on April 21, two days after Arevalo's death, a local media outlet received the video.

The footage, which went viral and made international news, is hard to watch. It captures the final throes of Woodroffe's 41-year-old life. He is slumped over in the mud, moaning, pleading, incoherent, his face beaten to a bloody pulp. More than a dozen onlookers casually stand by as a man fashions a noose out of a seatbelt, forces it around Woodroffe's neck and then violently drags him through the dirt until he is strangled to death.

The locals believed police weren't taking Arevalo's killing seriously, but the video evidence of Woodroffe's death spurred immediate action. On the same day the lynching video surfaced, dozens of police officers descended upon Victoria Gracia looking for the gringo's body, with the news media hot on their heels.

Investigators had received a tip that Woodroffe's corpse was hidden in a shallow grave somewhere, and before long, they found the body buried in a thicket of high grass. They also unearthed a 9-mm Taurus pistol and a dismantled motorcycle.

The hardest questions about this bizarre double killing wouldn’t be answered with forensic evidence. This was a tragedy shrouded in the mysteries and mysticism of the Peruvian Amazon.

Woodroffe had wanted to help people. He had wanted to be a healer. He had journeyed to Peru several times over the last few of years of his life to sit with Indigenous shamans and find enlightenment, which included taking a plant-based hallucinogen called ayahuasca.

To this day, Woodroffe's family and friends don’t believe he was capable of killing someone. But in the years prior to his gruesome death, they noticed changes in him — and what they saw wasn't enlightenment.

II.

Sebastian Woodroffe was a seeker. He was never interested in a conventional life.

"He had a strong philosophy that went against mainstream lifestyle," recalled his stepbrother Richard Dockrill. "He opposed consumerism, materialism and technology."

Woodroffe lived on Vancouver Island. He didn't have a career plan, but didn't seem to worry too much about money. He picked up work in construction, tree planting and on and off as a sea urchin diver.

The guys on the boats dubbed him Seabass, and said he was distant, wrapped up in his own world.

"From the minute I met him, I felt like he was lost and was trying to find himself," said fellow diver Mike Kelly. "He was the kind of guy you'd have a conversation with, and he would disappear — staring off into space. You'd ask him a question, and you would have to break him out of his thoughts. He'd just be gone entirely."

"He was one of those white kids searching for any kind of spiritual connection he could find."

Still, by most accounts, Woodroffe had a big heart and was genuinely concerned about others.

"Here's a man who always saw the beauty in struggle, you know, in the people who were in struggle," said Yarrow Willard, an herbalist on Vancouver Island, and a friend. "He knew all the homeless people in town."

Woodroffe would "give you the shirt off his back, give you his last dollar," said his father, Gary Woodroffe. "If you needed help, he'd always be there for you."

Sebastian Woodroffe was in his early 30s when he became a father. The relationship with his son’s mother didn’t last, but they remained friends, and Woodroffe loved the boy. The two of them would bond in the wilderness of the Comox Valley, swimming in Courtenay's Puntledge River and foraging for mushrooms in the forest.

Woodroffe would also teach his son about the healing powers of the plants all around them.

In addition to his love of nature, much of Woodroffe's adult life was spent trying to achieve spiritual enlightenment. He immersed himself in North American Indigenous culture, and participated in the annual Sundance ceremony, which meant fasting, praying and physically sacrificing his body. The ceremony involves piercing the skin with a hook and being tethered to a tree.

Mike Kelly recalled Woodroffe showing him his scars.

"He was one of those white kids searching for any kind of spiritual connection he could find," Kelly said.

Watching the Indigenous healers, Woodroffe became interested in learning as much as he could about plant medicines. He was also starting to learn about ayahuasca, an Indigenous medicine from South America that healers there had been using for centuries.

Steve Ellis, Woodroffe’s ex-brother-in-law, recalled turning him on to ayahuasca after attending a ceremony in Whistler, B.C.

"I was interested in physics, quantum mechanics, atoms, energy, crystals," Ellis said. It was after connecting with a community of "open-minded individuals" that Ellis had his first ayahuasca experience. "It was a really scary and profound life-changing experience. I shared [the details] with Sebastian, and he was really interested in it."

By 2013, Woodroffe's fascination with Indigenous culture, plant medicines and ayahuasca — coupled with an intervention for a family member struggling with alcohol — led him to a life-changing decision.

"I've decided to leave my current career behind and in September 2014, I am starting school, beginning a 6 year process to become an addictions counsellor," he declared in an IndieGoGo appeal.

His first step on this new career path was to start a crowd-funding campaign to raise money so he could study plant medicine and take ayahuasca in the Peruvian Amazon.

In this online video from 2013, Woodroffe talks about wanting a 'career change.' (Sacred Circle/YouTube)

In the crowd-funding plea, Woodroffe wrote that he had an opportunity to study for three months with a Shipibo plant healer in Iquitos, Peru. "This man comes from a long line of healers going far back into the mists of time," he said.

The healer allegedly had more than 40 years of experience using native plants’ potent capacity for healing, and Woodroffe was interested in learning "how they can be used successfully in the treatment of people with addictions. The more that I can learn and apply, the better I will be at helping in this line of work."

Woodroffe's campaign goal was to raise $10,000, which included $6,800 for the healing centre, $2,000 for travel and $600 for a Spanish translator.

He only raised $2,261, but he was undeterred. One way or another, he was going to Peru to sit with a shaman. His persistence would be his undoing.

III.

The Ucayali region in Peru is named after the winding tributary that feeds into the Amazon River.

An hour flight from Lima northeast over the Andes mountains takes you to the regional capital of Pucallpa, a bustling city of more than 200,000 that sprawls from the banks of the Ucayali into the surrounding rainforest.

The region is home to a number of Indigenous peoples, including the Shipibo-Conibo, who have lived in the rainforest for centuries. Marginalized and poor, the Indigenous peoples of the Amazon have been in constant conflict with powerful oil, mining and logging interests, which have stripped away much of the rainforest and polluted the waterways.

Over the past two decades, more and more Western tourists have been coming to the Peruvian Amazon in search of another natural resource, ayahuasca, a sacred medicine that Christian colonizers tried in vain to outlaw centuries ago. The Shipibo believe the visions conjured up by the hallucinogenic can help heal the body and mind.

Ayahuasca is a dark tea derived from mixing a leaf and a vine. The leaf, Psychotria viridis, contains dimethyltryptamine (DMT). Taken by itself, the leaf is benign, because enzymes in the stomach neutralize the DMT. But the Shipibo figured out hundreds of years ago that when the leaf is boiled down with the ayahuasca vine, Banisteriopsis caapi, it blocks those stomach enzymes, and creates a potent psychedelic brew.

Ayahuasca is not a recreational drug. The ritual is physically and mentally demanding. The curandero prescribes strict dieting and fasting beforehand, because the ceremony often starts by smoking a strong, sacred tobacco — mapacho — that, along with drinking the ayahuasca, can cause severe vomiting.

The drug trip can last three to four hours. Participants lie on mats in the dark and fall into a dreamlike state. The curandero will sing icaros. People who have taken ayahuasca say the visions can be intense and life-altering, often calling up past traumas buried deep in the subconscious.

"It's a fascinating compound, and until recently, it was largely unknown to the West," said Charles Grob, a psychiatry professor at the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) who has done field studies on the effects of ayahuasca in South America.

Grob said he has also found "the whole area of hallucinogens or psychedelics to be of great interest and great potential for future psychiatric treatments."

Psychotherapy that incorporates hallucinogens has been making a comeback in North America. With the efficacy of prescribed opioids coming under greater scrutiny, hallucinogens are getting a second look when it comes to treating depression and addiction.

In 2011, the CBC's Nature of Things followed doctor and author Gabor Maté to Peru, where he was exploring the use of ayahuasca to help patients in downtown Vancouver get at the root cause of their drug addictions.

"In the right context, with the right intention, with the right support system, ayahuasca can be remarkably therapeutic, and that's what's drawing Westerners down to the Amazon basin," said Grob.

Monetizing this ancient ritual has become a big part of the economy in Ucayali, and a major source of income for the Shipibo. A two-week ayahuasca experience, which involves dieting and ceremonies, costs thousands of dollars.

Maestro Olivia Arevalo Lomas was one of the most recognizable shamans in the Peruvian Amazon, and had worked at some of the ayahuasca retreats aimed at tourists. Members of Arevalo’s extended family also established ayahuasca retreats and became sought-after shamans themselves.

A small, frail-looking elder, Arevalo had a child-like demeanour that belied the fact that she was a powerful curandero.

"What struck me most about her was she was just full of kindness and light, and she would giggle and laugh," recalled Mick Huerta, an author and ayahuasca researcher.

Huerta, who grew up in St. John's, N.L., has travelled throughout South America and written extensively about it. He now lives most of the year in the Peruvian Amazon, where he is working on a new book called Ayahuasca, the Amazon Path to Yourself.

He said Arevalo held a huge amount of plant knowledge. Huerta said he was told that "a shaman of her level would know 500, 600 plants that can address a wide range … of maladies."

Huerta has met all kinds of people in the jungle, including soldiers who have come to treat PTSD, and others who have OCD.

"I'm a believer in the Western science," Huerta said, "but when there are holes in that, I believe that these people here in the jungle have the ability to heal things that we in the West have never ever been able to touch."

Woodroffe first journeyed to the Peruvian Amazon with the money he raised back home. He went to Baris Betsa, a retreat in Iquitos that was managed by Arevalo's cousin Maestro Guillermo Arevalo.

"The first time [Woodroffe] went to Peru, I was not concerned," said Yarrow Willard. "I thought, great, take this journey, find yourself, come back and probably you'll have some deeper insight and awareness."

The trip seemed to go well. When Woodroffe returned to B.C., he doubled down on his exploration into ayahuasca as a healing tool for himself and others.

Ayahuasca is illegal in Canada and the U.S., but there are underground ceremonies from coast to coast, often guided by gringo curanderos who have been trained in the Amazon. It's not uncommon for an organizer to fly a Peruvian shaman up north to guide a ceremony.

Woodroffe's former diving colleague Mike Kelly said he often overheard him on the phone, arranging ayahuasca ceremonies in Comox, B.C.

"They had a shaman that would come up and perform the ceremonies," Kelly said.

But right away, people in Woodroffe's circle sensed that something was off. He could be aggressive, and at times he seemed mentally unstable. The ayahuasca seemed to be hurting, not helping him. The organizers eventually told him he could sit in ceremony with them, but not drink the tea. But it didn’t matter — Woodroffe arranged ceremonies on his own.

Close friends and family also started to notice a change. He was obsessed with plant dieting. He was more introverted, and his personal life was in turmoil. Around this time, another long-term romantic relationship he was in broke up.

Willard, who has a philosophical way of speaking, had this theory: "Once he had seen beyond the curvature of his own earth on a number of occasions, that challenged maybe the mental paradigm he had previously believed in, and created a little bit of conflict and instability within himself."

"He was sad about the way life was going at this time, I guess."

"I know the idea," Willard said, "the dream of working with people as a healer, and helping support others' addictions was a really powerful [idea] that he held strong. Yet the reality of coming back to Canada, and having to work as a diver and having to step back into the real world, was a bit of a disconnect to that dream vision."

Woodroffe's father, who retired after serving four decades in the Royal Canadian Air Force, advised his son to seek professional help.

"He was sad about the way life was going at this time, I guess," Gary Woodroffe said. "We all have times in our life where things are down, and things come back up, and if you can get some help and you can get some assistance, then you can work your way through it."

What worried Woodroffe's family most was when they lost track of his whereabouts, only to learn that he was back in Peru.

On July 26, 2017, Woodroffe posted on Facebook: "Anyone like to see me. Feeling low. Reaching out." He appeared to be back in B.C.

But that summer, Woodroffe turned up in Pucallpa. A young American who would not give his real name but goes by Daniel Love recalled seeing Woodroffe walk into a café popular with expats.

Love, who was building his own jungle retreat in Peru at the time, said he saw Woodroffe have a strange conversation with one of his friends.

"As [Woodroffe] left, my friend came up to me and asked me, 'Do you know that guy?' And I said, 'Not really, I've just seen him today in the café,'" Love recalled.

To which Love's friend responded, "'Well, he just asked me for a gun.'"

IV.

Those who knew Woodroffe don't believe it. He wasn't into firearms.

"We've never had guns here at home, and have never even talked about them in any way, shape or form," said Gary Woodroffe. "So him getting a gun is totally, 100 per cent out of character — or even wanting a gun, he's never talked to me about it. And as far as I know, he's never talked to other family members about being down there and needing protection."

But Woodroffe was acting strange and at times desperate. In September 2017, he contacted the owners of the fishing company he had previously worked for in B.C. and asked for a loan.

Mike Kelly recalled Woodroffe contacting him as well around this time. Kelly said Woodroffe told him his wallet and passport had been stolen, and that he was hoping his former employers would loan him several thousand dollars.

Woodroffe didn't end up getting that loan, and he was back working on a boat in B.C. later that same month. But he didn't stick around for long. Two weeks before Christmas, Woodroffe’s dad drove him to the airport in Nanaimo. He was heading back to Peru.

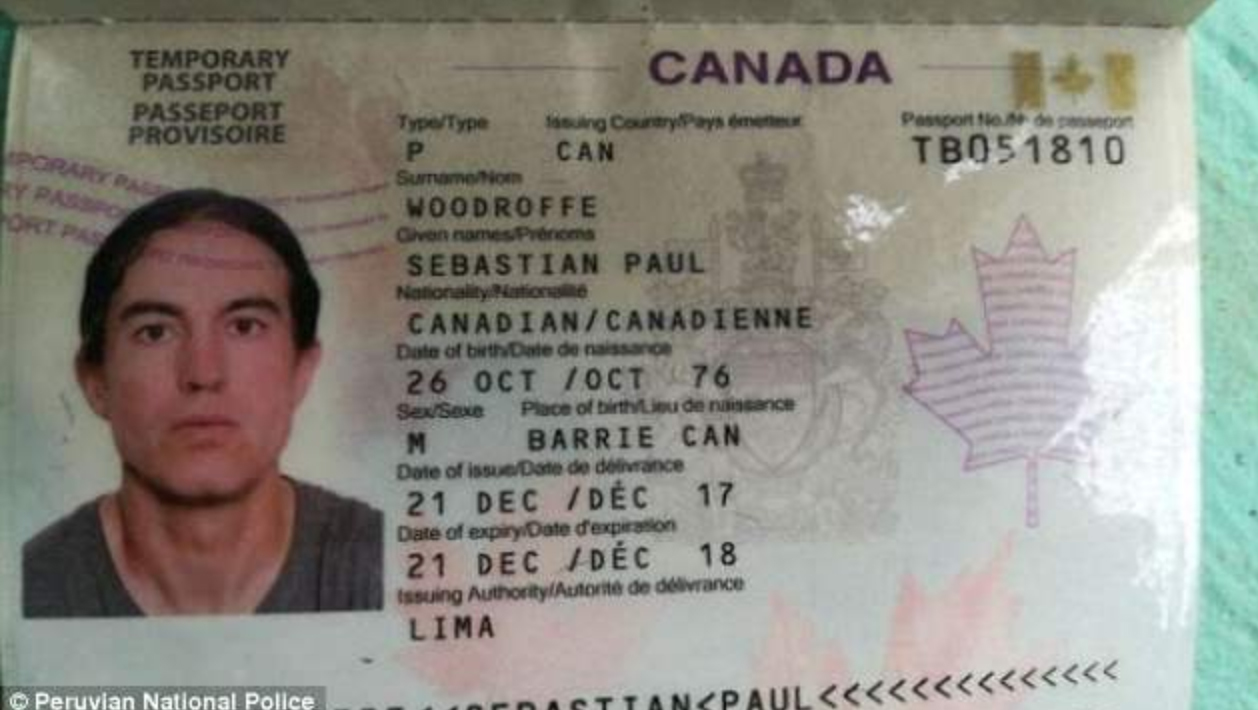

Woodroffe arrived in Lima on Dec. 15 and almost immediately ran into difficulty. He reported that his passport was stolen. Then he was involved in a collision in Lima while driving a rental car. While they waited for the police to arrive, Woodroffe and the driver of the other vehicle used their phones to communicate using an online translator.

The man thought Woodroffe had asked him if he knew where he could get a gun. The man thought the translator had interpreted incorrectly, or that he’d misunderstood. He responded by saying, "I don't know," and Woodroffe told him not to worry about it.

"Some neighbours found him prowling around there in the darkness. What was he trying to do?"

When he finally arrived in Pucallpa, Woodroffe sought out a taxi driver to act as a translator and help him locate the famous shaman Olivia Arevalo. He eventually found Herbert Ravelio, who drove him around town until someone was able to tell them where precisely Arevalo lived.

According to a statement Ravelio made later, they went to Arevalo's house in Victoria Gracia. Since Arevalo didn't speak Spanish, a villager translated for Ravelio, who in turn translated in English for Woodroffe.

Woodroffe asked the shaman if she could cure him and his family. Arevalo responded that she could, if he had faith. Woodroffe said he would talk to his family and come back soon.

Woodroffe returned to Victoria Gracia a while later, but something wasn't right.

Becky Linares, the mayor of Victoria Gracia, said Woodroffe would come by, insisting that Arevalo take ayahuasca with him. Arevalo refused. According to Linares, Arevalo hadn’t taken ayahuasca in years.

Woodroffe seemed obsessed with the Arevalo family. And his interactions with locals in Victoria Gracia were becoming more aggressive.

"He wasn't a normal person," said Linares. "Some neighbours found him prowling around there in the darkness. What was he trying to do?"

According to multiple accounts, Woodroffe turned up in the hamlet one night during a healing ceremony wanting to speak to Arevalo's son Julian. Woodroffe was reportedly carrying a long club, and was initially turned away from the lodge. He tried to sneak back, and apparently struck the man guarding the ceremony. Some villagers pursued Woodroffe, but other locals intervened to stop him from being seriously hurt, and ended up taking him to the police.

Linares said community members took Woodroffe to the police on three separate occasions. But local police have no record of this.

When Woodroffe failed to check in over Christmas and New Year’s, family and friends in B.C. became worried.

"Gotta ask ... does anyone know where Sebastian could be?" someone wrote on his Facebook wall on Jan. 3, 2018. "Family cares and has no idea --- please message me if you do, thanks!"

Two days later, Woodroffe posted, "I am alive."

He left Peru on Jan. 12. But something had soured his relationship with the Arevalo family. A number of rumours later circulated — that Woodroffe had given Julian Arevalo money for ayahuasca ceremonies that he never received, or that he had been ripped off after giving Julian thousands of Peruvian soles (the country's currency) to buy land to start a new retreat. The rumours have never been confirmed, and by all accounts Woodroffe was never that flush with cash.

Whatever it was, something had put Woodroffe on a collision course with the Arevalos.

V.

When Woodroffe returned to B.C., he was living in his RV. By all outward appearances, he seemed lost and confused about what to do next.

"Looking for a job, house ... basically a life," he declared on Facebook in February 2018.

"I miss my family and friends and feel like shit. I hope i am not sick," he posted a couple of days later.

Gary Woodroffe said that each trip to Peru "seemed to close him off to us."

"He wouldn’t talk about what he did on the trips, and he wouldn't talk about a lot of things that went on ... I implored him, I asked him many times ... 'Hey, let's sit down, talk about this, see where you're going, see what you want to do.' And he would put it off."

Woodroffe seemed consumed by internal conflict. "Whose [sic] going to Peru. I have lots of peruvian money to sell," he posted on Facebook at the beginning of March, suggesting he might be done with the place.

Then, a few days later, he decided he needed to go back. On March 11, he wrote this disjointed post: "i am.off to jungle.to.do some.sould searchin and fix the mind. see you whence.i am healed fml. part 4."

His friends and family questioned the decision and tried to talk him out of going.

Woodroffe's family and friends had had their suspicions that this was becoming a mental health issue.

"Are you sure these trips to the Jungle are healing you?" his former brother-in-law Steve Ellis messaged back.

In response to another concerned post, Woodroffe wrote, "Thanks. not gonna take the aya."

Yarrow Willard said that most of Woodroffe's friends and family were puzzled as to why he kept wanting to go south when he had a life in B.C.

"Most of us here in this part of the world that knew him well were like, 'Don't go back there,'" said Willard. "'Be here: You have a son, you have a life, you have a world here that you can be part of. Why are you going?"

There may well have been a deeper reason.

Olivia Arevalo's cousin Guillermo Arevalo said that Woodroffe contacted him before returning to Peru, asking if they could meet up at his centre in Lima. (They never did.) Guillermo also said Woodroffe told him he was bipolar, and that he wanted help.

Woodroffe's family and friends had had their suspicions that this was becoming a mental health issue, but he had never shared that with them.

Arevalo told Woodroffe he would be out of the country. Despite all the concern expressed by family and friends about going back, despite the conflict in Victoria Gracia just months earlier and despite his questionable state of mind, Woodroffe decided he didn't have a choice — he had to go back to Peru.

VI.

On March 14, Woodroffe was back in Pucallpa, but this time he wasn’t staying at a retreat. He was living in a succession of low-rent rooms he found in the hamlets around the city.

It's unclear if he was seeking help, but 13 days after arriving, Woodroffe posted on Facebook, "i am feeling better day by day in peru. so thankful to be sitting with good peeps." But he also added in a reply that, "I am leaving the place I am at due to a tribal disagreement."

Looking back now, the final weeks of Woodroffe's life seem dramatic and frantic. He was paranoid, and a darkness seemed to be blocking out his healing spirit.

On the morning of March 30, Woodroffe walked into a police station in Pucallpa and declared that he wanted to buy a gun. He eventually connected with Glauco Utia, a 25-year-old police officer on duty that day.

They communicated using Google Translate, and according to Utia’s later statement, Woodroffe explained that he needed a gun because he was going into the jungle and wanted protection from animals. Utia went along and asked him how much he wanted to spend. Woodroffe said he had 5,000 soles (about $2,000 Cdn), and Utia agreed to sell him a 9-mm Taurus pistol he owned.

Was Woodroffe planning a trip into the jungle? Utia is the only person to make that claim. But if it wasn’t true, why did Woodroffe believe he needed protection?

Though he had written on Facebook that he wasn’t going to take ayahuasca on this trip, it’s unclear if Woodroffe was adhering to a strict plant diet at this time, as he had before. Such a diet is part of the spiritual cleanse in Peru. But if it isn’t monitored by a shaman, it can have pitfalls.

Willard said Woodroffe had been dieting with white sage, which has long been used by Indigenous cultures to repel dark spirits.

"First off, anybody on these types of diet, it's like, they're not eating real food," Willard said. "Like their electrolytes, their protein, every base nutrient is being compromised. So yeah, they're getting this vision-quest type experience, slightly hallucinogenic, just from lack of good nutrition. But then they're also taking in these plants."

"Not enjoying life right. Having a rough go. please send me prayers..."

A Facebook post from April 1 suggests he wasn’t sticking to plants. Woodroffe wrote, "eating street meet [sic] in peru up till this point has been no problem…….until now. shitting in jungle day 3."

Over the next couple of days, Woodroffe and Utia arranged the paperwork for the sale of the gun. The fact that Woodroffe didn't have a gun licence apparently wasn't a problem. It also wasn't a deal breaker when Woodroffe said he could only come up with 3,000 soles. The sale was finalized on April 3.

On April 5, Woodroffe posted this on Facebook: "Not enjoying life right. Having a rough go. please send me prayers..."

A couple of days later, Woodroffe rented a room from a family outside Pucallpa. A member of the family agreed to loan him a Zongshen motorcycle in exchange for paying the insurance, about 90 soles.

On April 10, Woodroffe went to the airport in Pucallpa to seek out Herbert Ravelio, the taxi driver who spoke English. Woodroffe was planning to see Olivia Arevalo in Victoria Gracia later that day and again needed a translator. Ravelio agreed to meet him at Arevalo's house in Victoria Gracia.

According to a statement Ravelio later gave to police, when he arrived, Woodroffe was with a group of people. When he spotted Ravelio, Woodroffe told him he had actually found a shaman who spoke English, apologized for making him come out to Victoria Gracia, and agreed to pay him for his trouble.

Nothing more is known about this encounter. Indeed, on social media, Woodroffe sounded a positive note. On Facebook, he seemed to be looking ahead: "coming home soon and need a place to call home. PM friends if you know of anything." Two days later: "still looking for a place to live in Courteney. love my own place but open to a roommate. i cook."

But whatever was driving Woodroffe to look to a future back in B.C. didn't last. On the night of April 14, Woodroffe turned up at the police station in Yarinacocha, on the outskirts of Pucallpa, with Herbert Ravelio. Woodroffe told the police he had been robbed.

According to the police report and the later investigation, Woodroffe said he was out having beers at around 10 p.m. when he was approached by two men who identified themselves as police officers. They demanded he hand over his backpack, which contained his driver’s licence, passport, insurance and registration for the motorcycle and a cellphone. He apparently did so and they left. No alleged perpetrators were ever arrested for the robbery.

It wasn’t the first time Woodroffe had claimed to have lost his passport and cellphone in Peru.

If Woodroffe was carrying the 9-mm Taurus pistol that night, he had managed to keep it concealed. He allegedly packed it a few days later, on his final visit to Victoria Gracia.

VII.

Warning: This section contains graphic imagery

Woodroffe was up early on the morning of April 19. One of his housemates said he saw him leave on the motorcycle at 7 a.m. Another saw him leave again at 10:30 a.m. Woodroffe was carrying his backpack and allegedly told the landlord’s son that he was going to take ayahuasca.

He arrived in Victoria Gracia just before midday, and stopped outside of Olivia Arevalo’s house. Witnesses say Woodroffe called out for Julian Arevalo through the windows. Woodroffe shot the gun into the air. Julian Arevalo allegedly ran out the back of the house. Around the same time, Olivia came out to speak to Woodroffe.

Carlos Vilcahuaman, the district prosecutor leading the investigation into the deaths, said his team believes Arevalo and Woodroffe came face to face at the side of the house and Arevalo started yelling at him for firing the gun.

"The pressure, the conflict, being yelled at," Vilcahuaman said, itemizing the possible reasons for Woodroffe's alarm. "He points the gun and shoots her twice."

The initial story from villagers was that Woodroffe demanded an icaro from Arevalo before shooting her.

What exactly prompted Woodroffe to show up at Arevalo’s house that day, however, is still a mystery.

According to Vilcahuaman, the theory that Woodroffe had come to confront Julian Arevalo about a loan was never corroborated beyond some witness statements.

In his statement to police, Julian Arevalo claimed he wasn’t even at the scene when the shooting occurred. He said his mother came to visit him around 8 a.m. that morning at his house, which is about a 10-minute walk away. She left at 11 a.m., and he then left his house to get his kids at school. When he returned at about 1 p.m., he received a call informing him that his mother was dead.

By then, angry villagers had grabbed Woodroffe off his motorcycle. According to a witness statement, the mob pulled a pistol out of Woodroffe’s backpack.

They told people present not to call the police — they would mete out their own grisly justice.

VIII.

To this day, many of Woodroffe's family and friends don't believe he could have shot Olivia Arevalo. Despite all his troubles, killer didn't fit the profile of the man they knew.

"I find it hard to believe that this actually occurred," said Gary Woodroffe. "I just know my son."

Yarrow Willard said, "In my heart, I know that Sebastian would never have done anything like that."

While the video of Woodroffe's lynching went viral, investigators couldn't confirm exactly what occurred on April 19 in Victoria Gracia. In fact, initial news media reports suggested Woodroffe may not have been the perpetrator.

There were also questions about the ongoing investigation. Woodroffe's family and friends weren't confident that once the story faded from the headlines, Peruvian authorities would be inclined to get to the bottom of what really happened.

At the same time, locals in Victoria Gracia believed the authorities didn't care about the killing of Olivia Arevalo, and were only pursuing the case because it may have had something to do with a dead gringo.

Carlos Vilcahuaman knew all the criticisms, but he and police ignored them and just worked the case.

Since Woodroffe's body had been buried, it was going to make forensic testing tricky, though not impossible. At first, they didn't find any traces of gunpowder (lead, barium and antimony) on Woodroffe's hands, which led some to believe at first that he hadn't been the killer. But Vilcahuaman said further testing confirmed it.

"We've done various tests, both the police and the prosecutors," said Vilcahuaman. "And the most important of those tests are the traces found on Sebastian's hands and his sleeves."

As well, the three bullet casings found at the scene of Arevalo's death were all from a 9-mm Taurus pistol.

Investigators tracked the gun sale and obtained a notarized contract. Officer Glauco Utia wasn't bothered when he heard the news that the gun he had sold Woodroffe was found to be the one that killed Arevalo.

"I sold it legally, with paperwork," he said. "It's the responsibility of the person I sold it to."

Vilcahuaman said the gun sale was "irregular" but not illegal. However, he said they are now investigating whether Utia also provided the bullets for the gun, after initially telling investigators he had not.

Once investigators had satisfied themselves that Woodroffe had in fact pulled the trigger, the focus became finding and prosecuting his killers.

Police in Pucallpa are still seeking four men in connection with Woodroffe's lynching — Fidel Arevalo Mori, Nicolas Mori Guimaraes, River Griberto Rojas Rojas and Jose Ramirez Rodriquez, who was the mayor of Victoria Gracia at the time. They are all currently at large.

"You can't take justice into your own hands," Vilcahuaman said. "Sebastian, for what he did, had to face justice. The people who killed him have to face justice ... You can't respond to a violent, illegal act with another violent, illegal act."

The people of Victoria Gracia never wanted violence, said the hamlet’s current mayor, Becky Linares.

"It's a tranquil community," said Linares. "We've never seen anything like that — what Sebastian came and did to us."

Linares said she doesn't know what caused the rift between Woodroffe and Arevalo's family — only that the rest of the community is now stuck with the repercussions. Victoria Gracia didn't just lose a respected elder. The four wanted men were all breadwinners, and their families have now been left in limbo.

"For me personally as a woman, as a mother, I don't wish death to anyone," Linares said. "Neither the old woman nor Sebastian should have died like that."

In their quest for Woodroffe's killers, investigators gave little thought to his apparent motive for killing Arevalo.

For one thing, they paid little mind to the personal items they found in Woodroffe's rented room. The items included a book (The Happiness Equation), a long hunting knife, a wrestling mask, sleeping pills (zopiclone) and two other prescription drugs from Canada.

One of those prescriptions was Olanzapine, an antipsychotic drug used to treat schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. The other was Clonazepam, an anti-anxiety medication.

When a person is in a psychotic state, "you have a false perception of reality, you can become quite delusional and your judgment is skewed," said UCLA Prof. Charles Grob.

"So this individual may have misperceived others around him as being a threat to him. Whereas in reality they weren't — it was the amplification going on in his own mind, triggered by what could have been a destabilizing psychiatric state."

It's unclear if Woodroffe was taking ayahuasca on that last trip. But it is clear that ayahuasca and antipsychotics don't mix.

"There is a real cautionary tale here — to not mess with your spiritual self."

"If you have a bipolar condition, you are certainly at higher risk for having a destabilizing experience under the influence of ayahuasca," said Grob.

At the time of publication, the results of the toxicology tests on Woodroffe had still not come back from Lima.

Gary Woodroffe was unaware his son was taking an antipsychotic drug. Woodroffe has never watched the cellphone video of his son's killing, and doesn't intend to.

"I want to remember him as we knew him, as the kind, generous, loving son, brother, father, spouse, that he was."

Yarrow Willard views the deaths of Woodroffe and his Peruvian shaman as casualties on humanity's road to higher consciousness.

"There is a real cautionary tale here — to not mess with your spiritual self."

Additional reporting by Chelsea Gomez, Kimberly Ivany, Mark Kelley and Simeon Tegel