November 11, 2021

Warning: This story contains graphic content.

It’s 4:45 a.m. and the sun has not yet broken the darkness that hugs the cold stone walls of the sprawling gothic-style buildings overlooking the banks of St. Lawrence River in eastern Ontario.

A teenage boy slowly pulls on his exercise shorts and T-shirt as he reluctantly prepares for the first day of what he’s been told is a "boot camp," or exercise designed as discipline to "make him more of a man." The boy is a student and his trainer, or more accurately, his disciplinarian, is his computer science teacher.

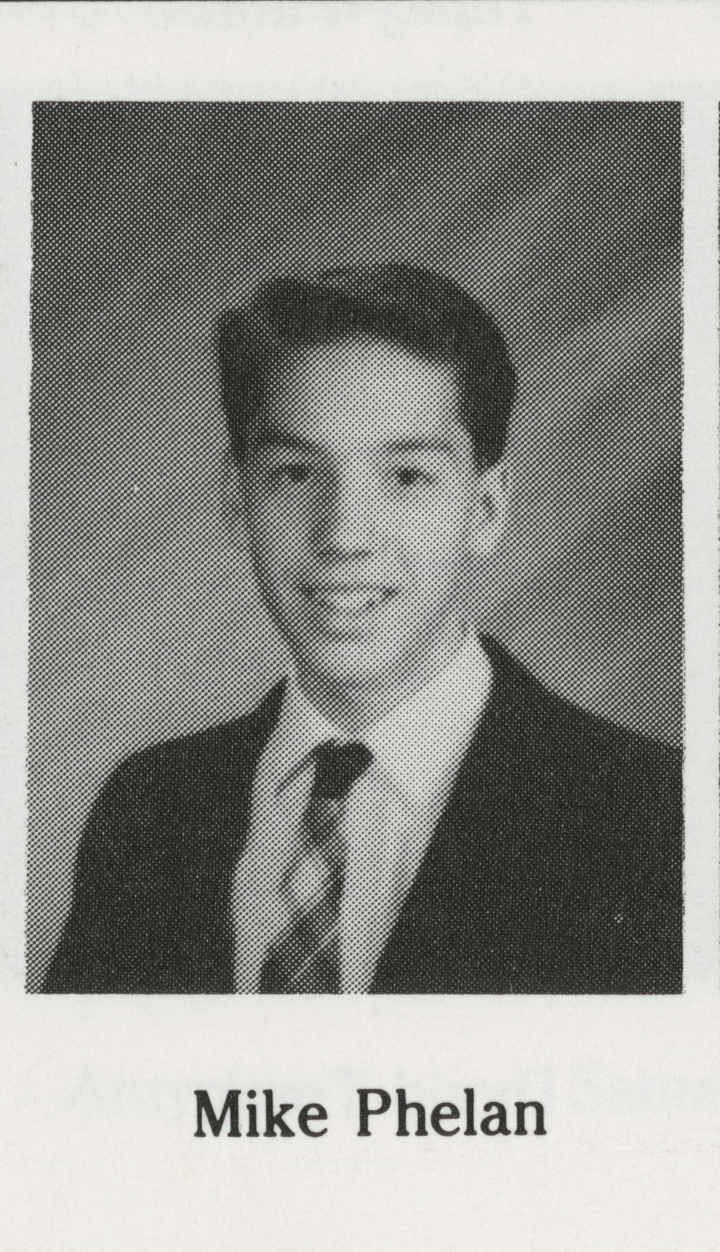

"I didn't know what to expect," Michael Phelan says as he recounts the details. "I just knew I was really scared."

- Watch "School of Secrets" on The Fifth Estate on CBC-TV at 9 p.m. Thursday or stream on CBC Gem

The plan that early winter morning in 1992, he says, was for the two of them to ride stationary bicycles in a small, windowless room attached to the school gymnasium as hard as they could for as long as they could.

"I just remember him yelling at me like ‘Harder, harder, harder,’ and I just remember I was so exhausted and I was in so much pain."

Afterwards, he stumbled to the showers. He was nauseous from overexertion and violently vomited. When Phelan told his teacher he had been sick, the response he says was cold and cruel: "Then we’re doing something right."

His teacher has denied making that comment.

Phelan says that "boot camp"-style discipline continued for months. Looking back, Phelan says he understands exactly what was going on with continuous references to the funny way he walked or how he was "too artistic."

"They're saying — whether you know it or not — you are espousing all the attributes of someone that is gay … and that's not happening on our watch," says Phelan, now 43 and living in Burlington, Vt. "Your soul's at stake.

"They were trying to do everything they could to beat that out of me."

WATCH | A former student says he was forced to do extreme exercise:

This was Grenville Christian College, an elite Christian boarding school affiliated with the Anglican Diocese of Ontario that catered to children of well-heeled families for more than 30 years.

In 2007, after it closed, it found itself in a cloud of controversy. Much of what went on behind those stone walls was exposed in a court battle that lasted more than a decade. In 2020, a judge’s ruling in a class-action lawsuit launched on behalf of nearly 1,400 former students left no room for wondering.

"Grenville knowingly created an abusive, authoritarian and rigid culture which exploited and controlled developing adolescents who were placed in its care,” Ontario Superior Court Justice Janet Leiper wrote in her decision.

"The evidence of maltreatment and the varieties of abuse perpetrated on students' bodies and minds ... was class-wide and decades-wide."

An investigation by The Fifth Estate has shed new light on the extent and depth of that abuse, including new allegations of sexual abuse involving senior figures at the school.

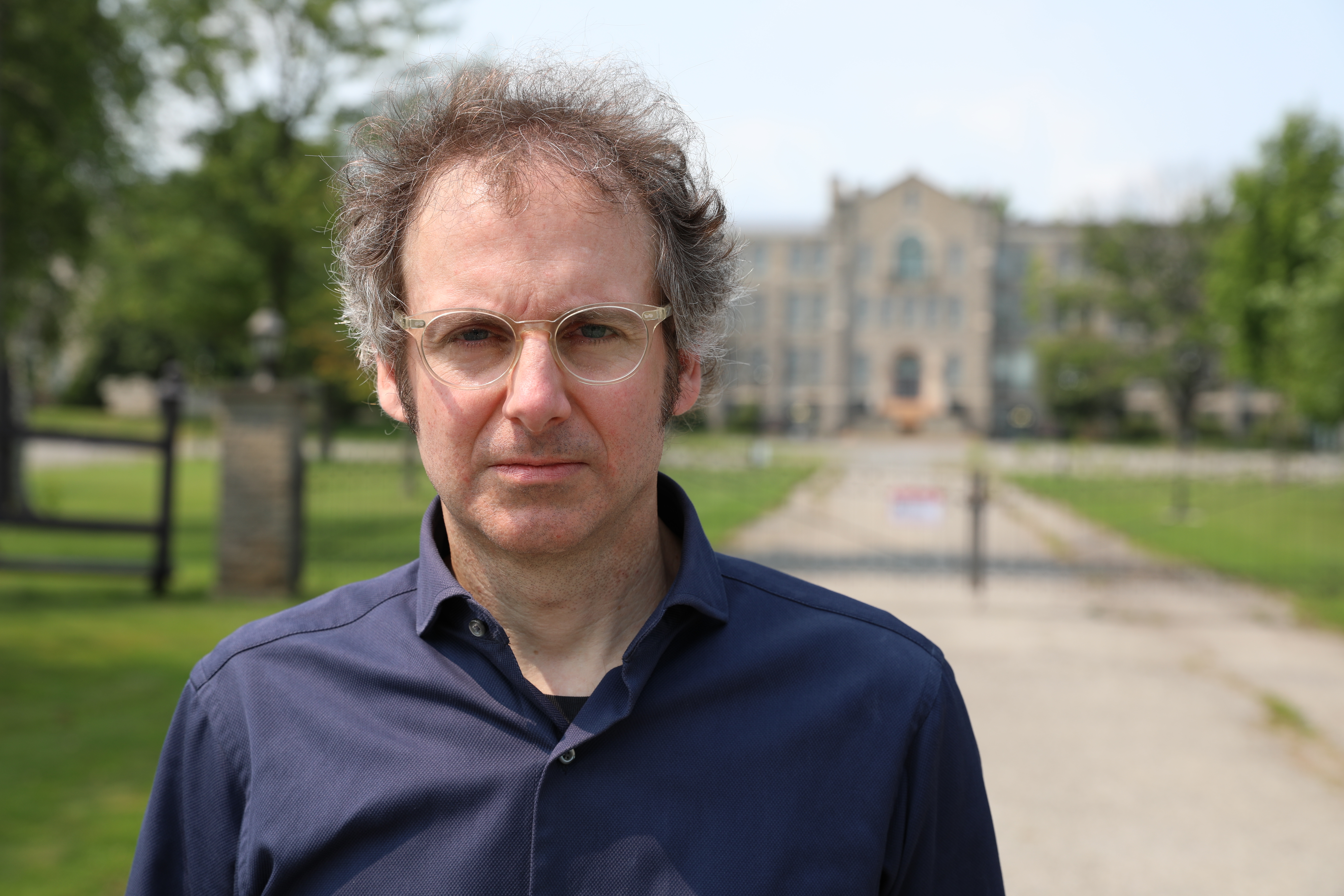

The Fifth Estate has interviewed lawyers, experts, police officers, journalists, former teachers, administrators and more than 30 former students, revealing allegations of sloppy police work, clear warnings ignored by the Anglican Church, a connection to a mysterious and abusive Christian cult in Cape Cod, Mass., and the role played by that computer science teacher, Gordon Mintz, a man who has since gone on to a senior position of trust in the Canadian military.

"[The school] ran very much like it was a cult. And so everyone was involved in all aspects of the cult all the time," says Rebecca Sangster, a former student who attended in 1986 and 1987.

Sangster paid close attention to the testimony in the class-action lawsuit, especially when Mintz took the stand.

"In the class-action lawsuit, he still defended the school, he still defended the faith," she says.

"Which to my mind means that he's still a member of the cult."

I.

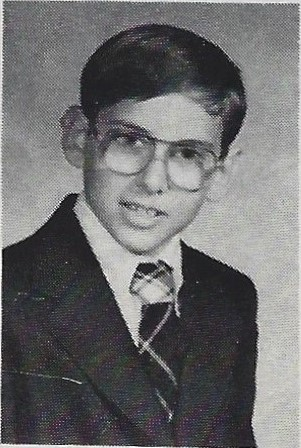

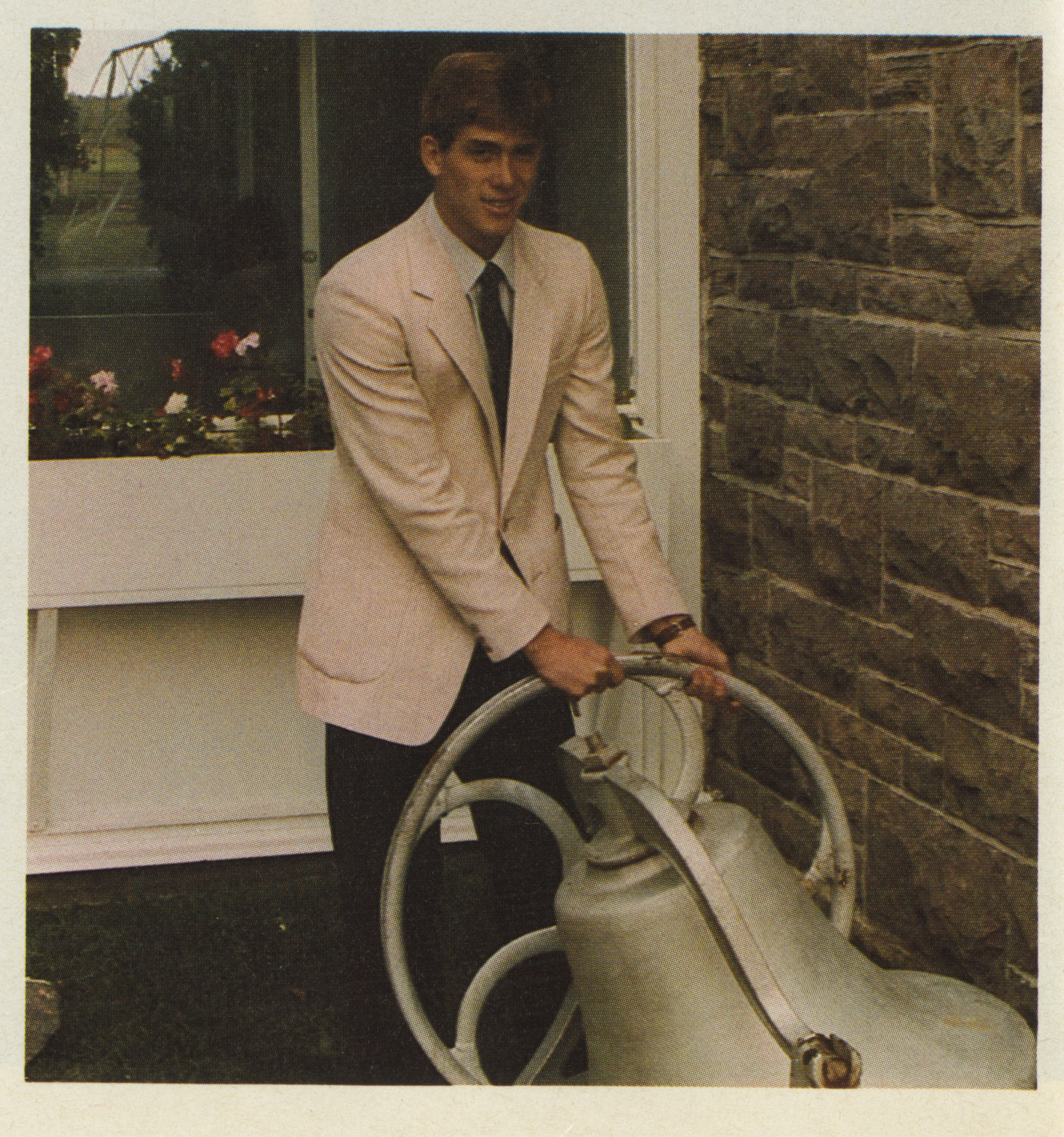

In 1984, Mintz received an urgent letter from his younger sister who was in Grade 12 at Grenville. According to an interview he gave Maclean's magazine in 1995, she told him she was being held prisoner, surrounded by a high fence patrolled by a guard dog.

"It sounded like a Nazi concentration camp run by a cult," Mintz told Macleans. He decided to investigate.

It was summer and Mintz was enrolled in the upcoming semester at the University of Toronto’s Wycliff College, a theological studies program described as following the Anglican tradition. He reached out and asked if he could visit Grenville.

WATCH | Grenville Christian College and its tough love philosophy:

That week-long visit turned into a career at the school that spanned 23 years, first as a maintenance person, then a teacher and eventually headmaster.

In 1995, Maclean's was profiling the school. In the end, the magazine published a glowing review.

Mintz told the magazine the fence imprisoning his sister turned out to be the "wrought iron gate gracing the entrance" and the guard dog was a "family pet" owned by the school’s headmaster. His assessment of the school at the time: "I had never seen a group of people more committed to the idea of maintaining integrity and caring about others. It really is like an extended family."

II.

It was Grace Irving’s first week of Grade 11, in 1996, and while students chatted excitedly about their summer holidays as they filed into Grenville's cavernous dining hall for breakfast, she was on her hands and knees serving a punishment as she scrubbed the carpet with a seven-centimetre nail brush.

"I can recall very clearly doing that," she told The Fifth Estate.

"Being on my hands and knees cleaning that carpet, praying, asking God to forgive me, and asking him to basically allow the people around me not to hate me."

Irving’s punishment would last five days. Referred to as being on "D," or discipline, she was forced to sleep and eat separately from her fellow students, banned from wearing the school uniform or attending classes and ordered not to speak to anyone.

"Discipline at the school was public intentionally," she says. "It definitely was humiliating."

Her offence: teachers searching her room found a friendly note from a boy. Boys and girls were forbidden from having any relationships whatsoever.

That week of discipline was the beginning of a downward spiral for Irving. She became ill. Then she stopped attending classes. Recurring nightmares started involving the headmaster, Charles Farnsworth. Memories from her childhood were haunting her.

"I just was so afraid of him for so long, really probably until he died."

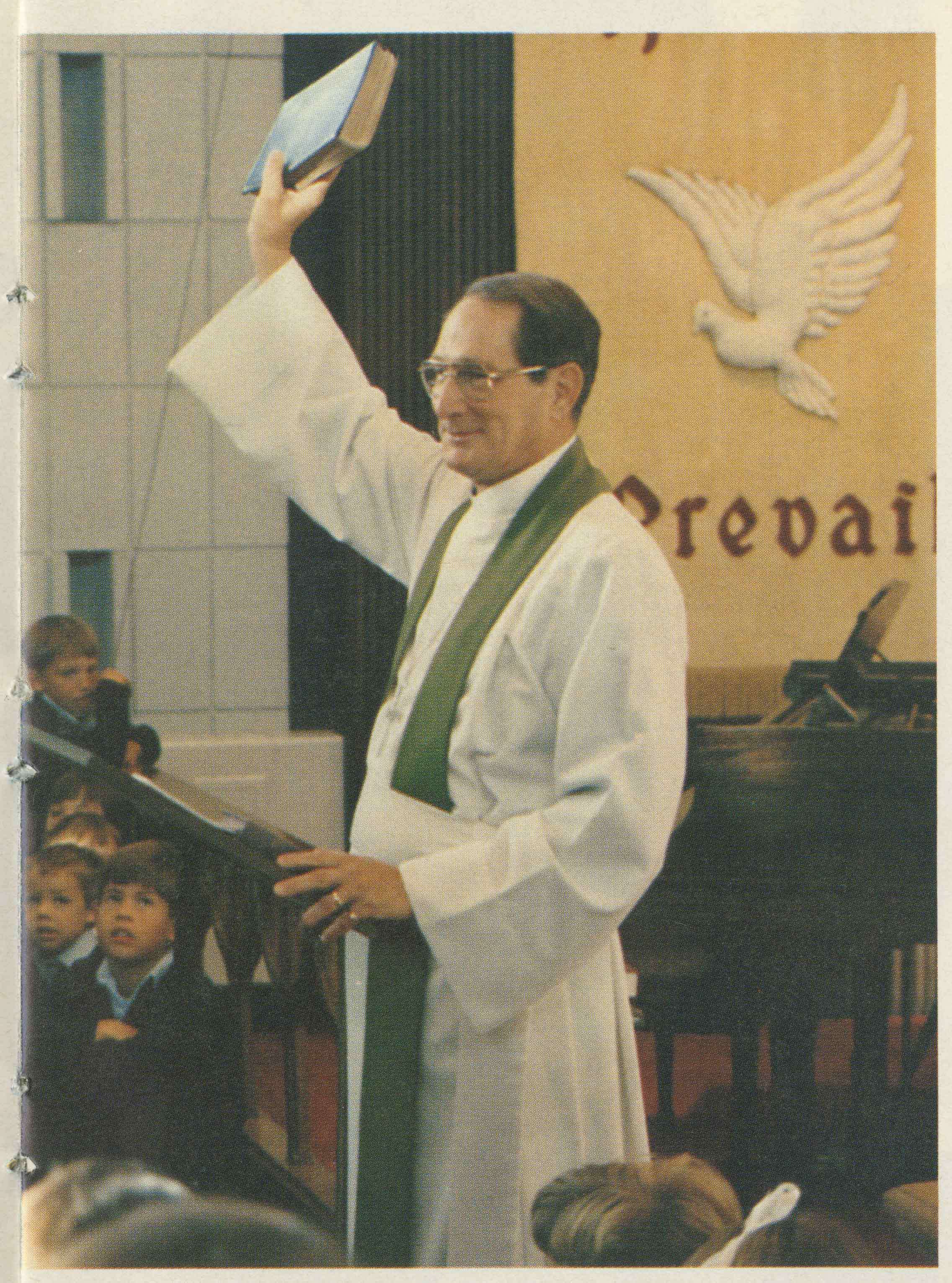

Described in the Maclean's magazine profile as a "warm Anglican priest with a down-home style," Farnsworth was one of two original headmasters at Grenville. He was ordained as a priest in 1977, when the Ontario diocese of the Anglican Church threw its support behind the school, flying its flag out front. From that time on, Grenville was known as an Anglican boarding school.

The school attracted the attention of prominent Canadians.

The board and advisers included a senator and two former Ontario lieutenant-governors. Charles Farnsworth and his wife met with the prime minister of the day, Brian Mulroney.

However, according to the lawsuit and interviews with former students, the school and its headmasters pushed philosophies and practices that had nothing to do with the Anglican faith or typical Christian values.

III.

Girls were chastised for behaving like "prostitutes" and being too tempting for men, while boys suspected of being gay were subjected to homophoic slurs and told they would be "damned to hell," the judge in the class-action lawsuit found.

One former student said he endured 20 "conversion" sessions because staff believed he was gay. Another was told it was his fault for "tempting" his abuser when he was sexually molested as a child.

Former students say these practices were often enforced with violence.

"There's lots of slapping," says Ewan Whyte, a student who attended in his early teens, from 1980 to 1983. "They'd beat the children with belts sometimes."

Phelan, Irving and Whyte were what was known as "staff kids." Their parents worked at the school, some of them as teachers, and because of that, they lived there year-round.

The staff kids had no choice in how they lived, but that wasn’t the case for their parents.

Donna Robertson was one of those parents.

"I wish I'd have stopped a kid in the hall and … had the guts to stop and say what are you on discipline for or can I help you?" she says.

Now 82, she is speaking publicly for the first time. Robertson was an employee at the school for more than three decades, first operating the daycare and eventually was a guidance counsellor.

"When I look back now, I think where the heck was my head?"

IV.

Nearly 800 kilometres from Grenville Christian College, a four-storey stone tower adorned with a life-sized bronze angel pierces the Massachusetts sky. Next to the tower, just visible above the surrounding trees, is the roof of a giant stone basilica.

The buildings are a strange sight for sure, made even stranger by their location overlooking the picturesque shores of Cape Cod. It’s an area better known for the East Coast beaches where Jaws was filmed and quaint harbours where fishermen sell fresh lobster rolls to hungry tourists.

A stone sign identifies the buildings as simply the Community of Jesus.

"[It’s] essentially a cult that has managed to maintain itself and grow over 50 years," says Ruth Marshall, a religious and political studies professor at the University of Toronto.

She has studied its history, philosophies and the way its leaders exert influence over members.

"It really was a complete system of surveillance and control. And they managed to do this mostly with a kind of psychological pressure ... that's what makes a cult."

The controversial Christian community was founded in the 1960s by two middle-aged women, Cay Andersen and Judy Sorensen, known as the Mothers, now both deceased. New leaders have taken their place.

The group's website says it has 275 members, most of them living at the compound in Cape Cod. It describes itself as a nondenominational Christian community living together with a common commitment to love.

Audio tapes of sermons obtained by The Fifth Estate offer another window into it.

"We don't call promiscuity today whoredom. I don't care what we call it. That's what it is. Whoredom," one of the mothers tells their congregation in the 1970s.

"Today, we have a generation of whores, and some of them are your sons and daughters."

According to former members, if they ever wanted to leave, they were told they would die and go to hell.

Carrie Buddington lived at the COJ for 41 years. She became a head sister and helped run the community. Now she's an outspoken critic.

"I soon learned that strict obedience means [the Mothers] were the voice of God…. They knew what God's will was for you," she says, explaining that she lived in a constant state of fear.

"So what they said you did."

Life in the compound often included violence.

"I had vomited at a meal and they said, 'You're going to eat it,' " says Ewan Whyte, who moved to the COJ with his family in the mid-1970s.

"An adult cult member there was pounding my head on the floor and ... was hitting me and I'm scooping it up off the floor and I'm eating my own vomit."

Whyte spent four years at the Community of Jesus before he and his family travelled north, to Grenville Christian College.

V.

One afternoon in 1973, a dusty white Winnebago turned off Highway 2 in eastern Ontario, drove past the iron gates and up the driveway to Grenville Christian College. It had finished a long trip from Cape Cod. The Winnebago pulled to a stop and out stepped the Mothers from the Community of Jesus.

"I can still remember the first day when Cay and Judy came ... then everything went topsy turvy," says Robertson, the longtime Grenville employee. At the time, the school was just starting up and still finding its feet.

"They were coming to fix us."

The Mothers had been invited to Grenville by the school leadership, who knew them through religious circles. According to the lawsuit, that's when the extreme and abusive discipline began.

"We all know that Cay and Judy ran [Grenville] from a distance," says Buddington.

"Farnsworth was under their authority.… There was a big connection. A strong connection."

The Community of Jesus, however, has repeatedly denied that connection and any role in the abuse that took place at Grenville that has been confirmed by the Canadian courts.

"I know you have a take. I happen to think it's grotesquely unfair and that it's hugely sloppy," the COJ’s Boston-based lawyer, Jeffrey Robbins, told The Fifth Estate in an interview.

“You accuse these two women and because they believe in Christian fellowship or whatever, that somehow acts over the course of a half century, of insulting people [at Grenville] were at the direction of the Community of Jesus.

“It's preposterous and frankly it should be offensive to anybody who cares about fundamental fairness.”

While Robbins denies any connection between the two organizations, an investigation by The Fifth Estate has uncovered a number of documents that suggest otherwise.

A deed registered in Cape Cod, shows Grenville purchased property directly adjacent to the Community of Jesus in 2001.

A corporate document called a Special Notice was filed with the Ontario Ministry of Consumer and Commercial Relations in 1986. It lists Sorensen and Andersen and later the woman who followed them as leader, Betty Pugsley, as corporate directors for Grenville Chrsitian College.

And, finally, a letter written in 2001 obtained by The Fifth Estate from a Grenville administrator to the Anglican bishop of Ontario says: "The Community of Jesus saved us from closing up in the early '70s."

"From that time on, they played a very major role in the lives of the leaders of our community … and therefore a major role in how many things were done up here."

The Canadian judge hearing the class-action lawsuit called the separation of the two entities a "false distinction."

"The [Community of Jesus] was the physical and spiritual home to the school. Its values, practices, hierarchy and beliefs were applied to the operations of the school," Leiper wrote.

"The two were interwoven."

The two organizations were so interwoven that members from each group travelled back and forth for retreats or visits, including one in 1986 involving a future teacher and headmaster.

At the time he was working at Grenville as a maintenance person, and, according to trial testimony, he was considering a permanent move to the COJ in Cape Cod. His name was Gordon Mintz.

VI.

In 2019, Mintz was called to testify against his former students in the class-action lawsuit. By that point, he had been an Anglican chaplain in the Canadian military for more than a decade, holding the rank of lieutenant-colonel.

During his testimony, he denied witnessing any excessive abuse during his 23 years at the school.

"I think ... people were very glad for the chance and the privilege to go to Grenville," he told the court.

"Overall it was very positive. People by and large enjoyed the activities and the sense of family."

The lawsuit covers the period before Mintz became headmaster, but includes his time as a teacher — slightly more than a decade in all.

In court, he was never questioned about sexual abuse, nor was he personally named in the lawsuit. But as a witness, he repeatedly denied any knowledge of physical or emotional abuse, which the judge had concluded was then widespread at his school.

"He was there for some pretty horrendous psychological, physical abuse of children," says former student Rebecca Sangster.

"And there's no way he can say he didn't know it was going on."

Mintz’s adamant defence of the school and its philosophies, she says, is proof enough for her that he still believes in what she calls the cult of Grenville and the Community of Jesus.

According to his testimony, Mintz went to the COJ again in 2008, after Grenville closed, and again for what he described as a "personal retreat" in 2014, eight years after becoming a military chaplain.

He also testified his mother lived there for eight months and that his wife's twin sister lived there at the time of his testimony in 2019.

While he said his connection to the Community of Jesus is not an "active relationship," he did admit to swearing a life-long commitment to the group.

"Gordon Mintz is completely complicit ... as are all of these ongoing members of the community," says University of Toronto’s Marshall.

According to three former students interviewed by The Fifth Estate, Mintz was also personally involved in multiple instances of extreme emotional abuse at Grenville.

In another account, a former student says he was repeatedly verbally attacked by Mintz while showering.

"I was body-shamed and Gordon would yell and add that I was fat and disgusting," Brad Merson wrote in an email to The Fifth Estate.

A third student wrote to say he, too, was "terrorized" by Mintz.

"Gordon Mintz was the ringleader of the bullies and he groomed other students to bully me in ... the middle of the night," wrote Paul Wachmann, who attended Grenville between 1997 and 2000.

WATCH | The Fifth Estate approaches Mintz to talk about his time at Grenville Christian College:

Wachmann says the attacks led him to attempt suicide while he was at the school.

In court, Mintz denied any involvement in any emotional abuse at the school. And what about his take on his predecessor, headmaster, Farnsworth?

On the stand, Mintz admitted his former boss's approach "wasn't necessarily as healthy as it could be." The Fifth Estate, however, has learned the allegations against Farnsworth went much further than what came out during the trial.

VII.

It was March break in the late 1980s, and Phelan was excited. He was about eight years old at the time and had been invited with a group of boys to the headmaster’s house for a sleepover. He felt special.

When he found out Farnsworth was going to let him watch Goonies, a popular movie from the 1980s he had been forbidden from seeing, he was over the moon.

Farnsworth’s 18-year-old son Robert was also going to be there. Robert used to take Phelan and another young boy to get ice cream.

But later in the night, after everyone was in bed, Phelan says he was woken up by someone in his room. It was Robert.

"I just remember I was lying on the ground, I had red striped pyjamas and I remember him taking the red striped pyjamas off of me. And I just remember him fondling my genitalia. I remember seeing him fondle the genitalia of the other boy as well."

Later that night, he says he got a visit from Robert’s father, headmaster Farnsworth.

"I just remember he had such a distinctive voice.… I remember that voice just saying 'Michael, Michael' over top of me. And I remember him fondling me as well."

After that night, he says the abuse continued and escalated.

Like him, Grace Irving has painful memories that began as nightmares in her Grade 11 school year.

She disclosed the details to her parents for the first time in 2001, when they finally agreed to move away from the school.

"And at some point after that I felt safe and comfortable, you know, to tell them that I had been sexually abused by Charles Farnsworth as a child."

Farnsworth died in 2015. His son Robert didn’t respond to requests for an interview.

Farnsworth's other son, Don, who was also a senior administrator at Grenville while it operated, responded to an email from The Fifth Estate denying the allegations of sexual abuse, saying they are untrue.

Don Farnsworth also approached The Fifth Estate crew while we were filming at the now-shuttered school, denying all accounts of abuse at the school.

"Often stories like this start out with 'Once upon a time.'

"I believe that systematic abuse is terrible, but I don't believe that happened here. There was no one here that had any intention of harming any child."

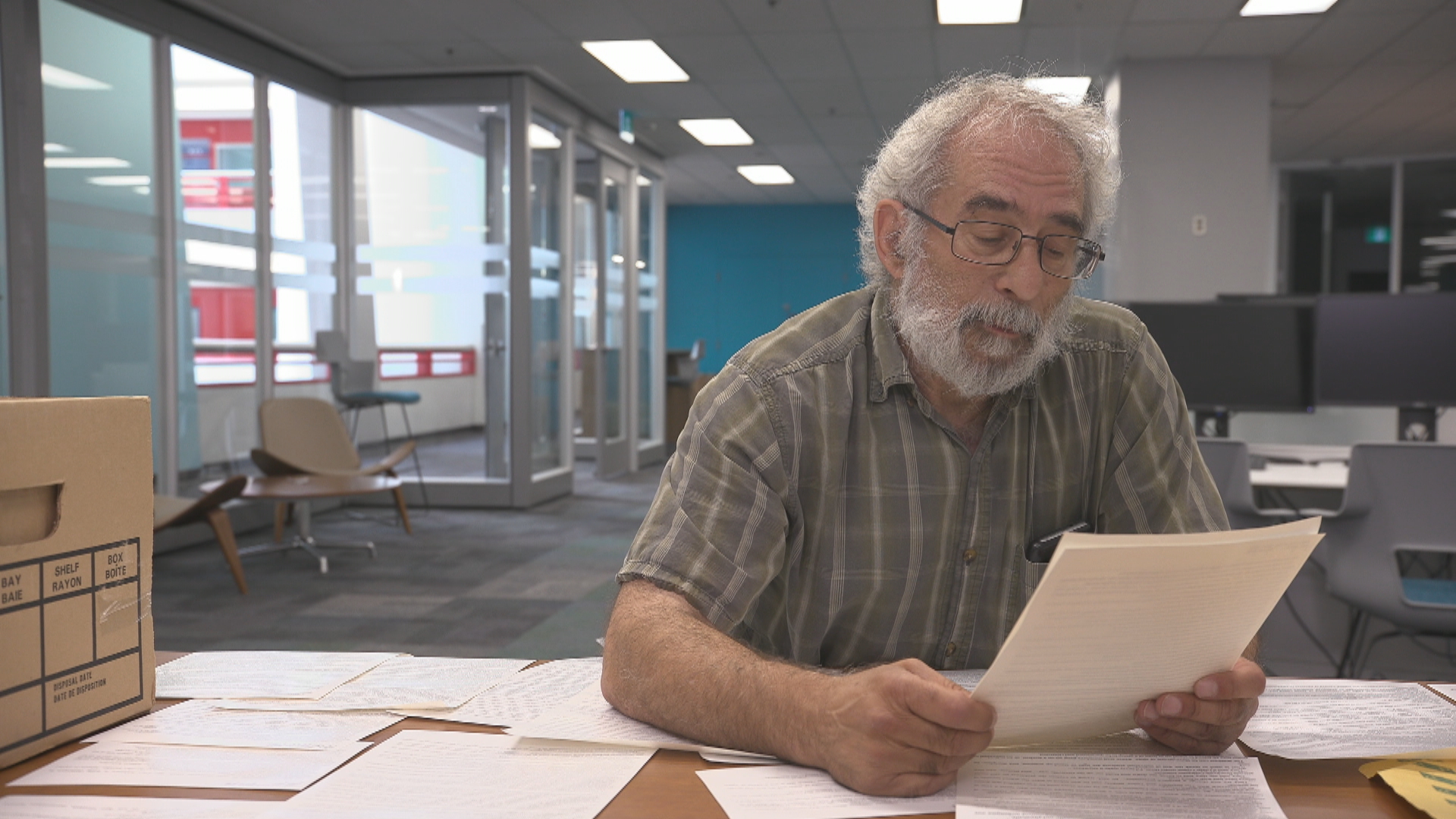

Warnings about abuse, however, go as far back as 1989, The Fifth Estate has learned. That’s when a local journalist investigating the school passed his findings to the Ontario Provincial Police and a senior member of the Anglican Church.

"The specifics I would have had would have been about separating the families ... discipline, psychological emotional abuse," says Mike Moralis.

He says neither the police nor the Anglican Church showed any interest in what he'd found.

A letter obtained by The Fifth Estate written to the Anglican bishop of Ontario in 2001 from a senior administrator at the school shows at least one person was concerned about abuse at Grenville, although she appeared to be more concerned the authorities would find out.

The writer informed the bishop about Irving's sexual abuse account involving the headmaster.

"What happens if this young lady goes to the police?" the administrator asks the bishop. That will be "devastating" for Farnsworth, she writes.

"What if this opens the door to all the other accusations that have come our way?"

When asked about the warnings in the letter, the Anglican Diocese of Ontario acknowledged receiving them, but pointed to a court decision that found it had "no duty of care" in the Grenville case and that there is "no evidence [it had] any direct involvement" in any abuse at Grenville.

The church says it didn’t go to the police about the accusations against one of its priests because the author of that letter "disbelieved the allegations" and "never informed the bishop of the identity" of the alleged victim.

But why would any of that stop the church from going to the police?

"Jurisdictionally it's frankly a nightmare to try and connect the dots between the Anglican Church [and Grenville], but there's clearly a great deal of complicity," says Marshall, who has studied the relationship between the two organizations.

"There's clearly a moral and ethical responsibility."

Seven months after it was warned about allegations of sexual assault involving its priest at the school, the Anglican Diocese of Ontario ordained another priest who would become a headmaster there, a man by the name of Gordon Mintz.

VIII.

On a June morning in 2019, a group of Canadian military officers, wearing crisp black uniforms and chests full of medals, gathered in the Vice-Regal Room of the Officers' Mess at Canadian Forces Base Borden, about 100 kilometres north of Toronto.

They were celebrating the promotion of a colleague who was taking command of the Canadian military’s chaplain school: Lt.-Col. Gordon Mintz.

Ten months later, the judge in the lawsuit against the school where Mintz had worked released her decision, finding widespread and systematic emotional and physical abuse. Although the judge made no finding against Mintz, or individual staff members, she found widespread and systematic emotional and physical abuse at the school.

"I took the judge's decision and I emailed it to [Mintz’s commanding officer], with an explanation saying, 'This is what you have allowed your padre to stand for. And I think that's shameful," says Sangster, the former Grenville student who, by coincidence, works as a civilian employee in the Canadian Armed Forces.

She received a reply the next day from Maj. Gen. Guy Chapdelaine saying he "had not been made aware of the issues described in her email until very recently," that they are “most concerning” and that an investigation has been launched.

Two years later, she has heard nothing back.

Mintz refused repeated attempts to have him answer questions from The Fifth Estate.

Capt. Bonita Mason, director of chaplain strategic support and chief of staff to the Chaplain General, told The Fifth Estate their investigation found “no irregularities” in Mintz'z hiring process.

She added that Mintz "is a wonderful individual" who has an “impeccable record” with the Canadian Armed Forces.

"He gives generously to the Anglican diocese and to different projects that deal with mental health. He is well-liked and has a lot of very good friends and colleagues within the [Canadian Armed Forces]."

However, she says the military was unaware of the specific allegations of emotional abuse against Mintz until contacted by The Fifth Estate. She was also unaware of his testimony in the Grenville lawsuit that has since been contradicted by a finding from a Canadian judge.

Mason says unless Mintz faces criminal charges, no action will be taken by the military.

The OPP did launch a criminal investigation into abuse allegations at the school in 2007. Phelan, Irving and Whyte were interviewed.

In the end, no charges were laid. The outcome wasn’t a surprise to any of them, given the OPPs history of failing to investigate the school.

"The fact that the same branch of the police would be allowed to do an investigation is shocking, absolutely shocking," says Whyte.

After being contacted by The Fifth Estate, the OPP says it has launched a review of its handling of the case.

So who is to blame for all that happened to the kids of Grenville Christian College: the church, the police, the cult in Cape Cod, the individuals involved?

"I think it's probably a mixture of all of the above," says Irving.

However, what Irving and others want most is for those involved to admit their roles and apologize.

"I think it would be helpful for me and for many people if we felt like there were people taking accountability for what happened, if people were taking responsibility. I think that would help," Irving says.

"And at the same time I think some of the damage is kind of irreversible."