October 13, 2019

Énergie Saguenay, a proposed $14-billion pipeline and LNG terminal, is the largest private investment project in recent Quebec history. But do Saguenéens want it?

CBC Quebec travelled through the region to find out what's at stake. Here is the second in a series.

The town

Nancy Lavoie’s rustic log home overlooks the lush, green hills leading into Sainte-Rose-du-Nord, at the foot of the Monts-Valin mountain range in Quebec’s Saguenay region.

“I moved here because it’s an incredible place, with charm and tranquility. It’s the front door to Quebec’s wilderness,” said Lavoie.

Sainte-Rose-du-Nord is one of several small towns strung along the Saguenay Fjord, where cliffs rising as high as 500 metres above the river provide views so breathtaking that locals have tried, unsuccessfully so far, to have the fjord recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

With its deep sea ports in La Baie and Grande-Anse and a course that ends in the St. Lawrence Estuary, the Saguenay River is also an attractive navigation route for industries wanting to ship their products abroad.

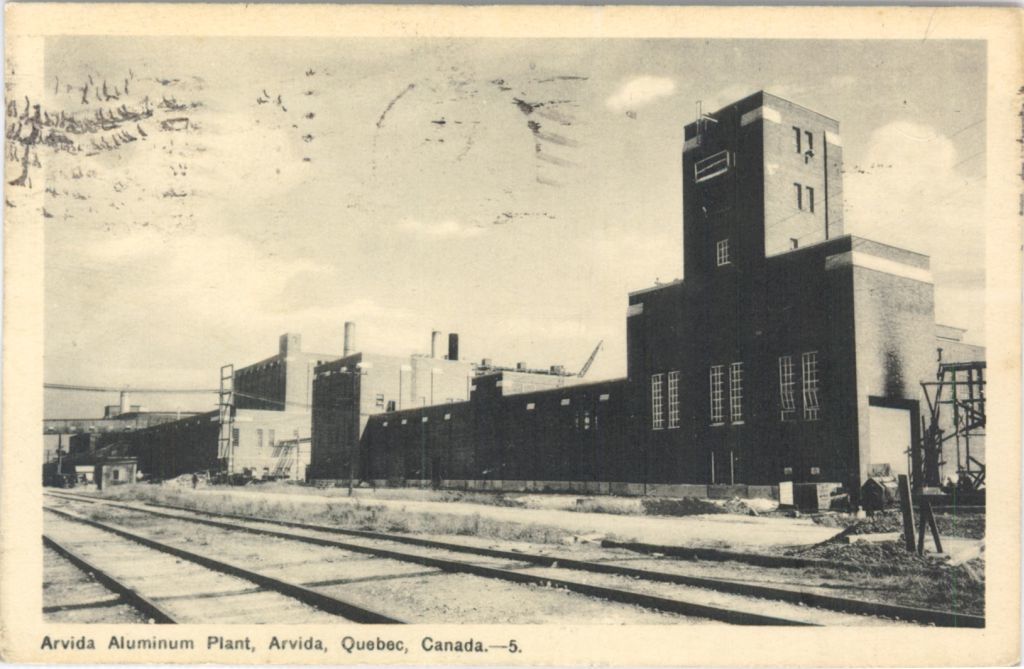

The 250-metre-deep fjord, a trough carved by glaciers of the last Ice Age, is what allowed Quebec’s Saguenay region to become one of the world’s most important aluminum producers.

Throughout the 20th century, ships carried bauxite into the fjord to feed the region’s smelters, where it was transformed into aluminum and shipped out by rail.

Before it was sold to Rio Tinto in 2007, the aluminum giant Alcan employed generations of Saguenéens, including several members of Lavoie’s family.

Lavoie often feels stuck between those two realities — her love for the majestic fjord, and her recognition of the role industry, and her own family’s hard work, have played in building the backbone of the Saguenay region’s economy.

“My dad, my grandfather, my uncle: everyone worked for Alcan back in the day,” said Lavoie.

Lavoie broke with family tradition and became a biologist at the nearby Saguenay-St. Lawrence Marine Park.

But she fears the way of life she’s chosen for herself and her children could be jeopardized if a liquid natural gas (LNG) plant and a marine terminal to ship the product to international markets are approved and built in the next few years.

With an unemployment rate of 5.3 per cent, the fourth-highest in the province, the Saguenay is hungry for jobs, and promoters know it.

Lavoie’s aunts and uncles tell her the region shouldn’t turn its back on well-paid work — an argument the biologist said doesn’t necessarily resonate with her generation.

“Sure, you have a good salary, but there wasn’t necessarily any quality of life in these big factories,” she said.

Company representatives are hearing those conversations play out as they drive up and down the winding roads to promote the project, called Énergie Saguenay.

Worth an estimated $9.5 billion, it may be the largest privately funded industrial project in Quebec history.

The natural gas liquefaction plant would be built on land owned by the Saguenay Port Authority, at the Grande-Anse Marine Terminal, 20 kilometres east of the city.

It would also require the construction of a 782-kilometre pipeline extending from where that pipeline now ends in northern Ontario to Saguenay — another $4.5-billion investment.

But selling that vision to locals, many of whom are trying to turn the page on the Saguenay’s industrial past to focus on ecotourism and the region’s natural beauty, is a hurdle the project’s promoters are facing in every village in which they stop.

In Sainte-Rose-du-Nord one recent September day, European tourists hopped off a chartered bus, stopping for a soft ice cream cone dipped in maple syrup glaze.

As they walked towards the wharf, they were met with cardboard signs on people’s front lawns that read: “No to a 3rd port on the Saguenay Fjord.”

The “third port” is yet another project slated for the region, which would be built to ship apatite, a primary source for fertilizer, from the Arianne Phosphate mining site. For now, the mine is on hold, but both the mine and the port have already been approved by both levels of government.

One of those posters hangs on Lavoie’s front porch.

She calls it “illogical” to build yet another port upstream from the protected marine park.

The cumulative effect of all the industrial projects proposed for the region is what Lavoie said is sparking debate in the Saguenay.

“I’m against the speed in which these projects are being presented, one after the other,” said Lavoie.

Énergie Saguenay still has to jump through several hoops before the project can proceed, however. Both the provincial and federal governments will undertake environmental reviews once the proposals are final.

Lavoie hopes the governments will listen as respectfully as her own relatives have when the issues come up at family dinners.

“When you give them counter-arguments, my aunts and uncles, they agree that it’s up to [my generation] to decide.”

The city

On a remarkably warm September morning, there are few pedestrians out on Racine Street, downtown Saguenay’s main drag.

Empty storefronts are a sign the economy of Saguenay, population 146,000, has seen better days, said Sandra Rossignol, the general manager of the local chamber of commerce and industry.

The region lost 22,000 young workers between 1996 and 2006, she said.

That’s why the chamber, backed by 18 local businesses, wrote an open letter expressing its support for Énergie Saguenay and the potential spin-off benefits the project could bring to the city.

“The region needs new projects to diversify its economy and to be less vulnerable to price fluctuations,” said Rossignol.

The promise of 1,100 direct and indirect jobs in a region that has witnessed the exodus of young families is hard to ignore, despite the environmental concerns being raised.

“We have to welcome these projects and wait for the environmental reviews before dismissing them,” Rossignol said.

Those reviews will be done by the Impact Assessment Agency of Canada, and its Quebec counterpart, the Bureau d'audiences publiques sur l'environnement, or BAPE.

The impact the plant would have on Canada’s greenhouse gas emissions is one important question people want answered, but so is the effect of shipping LNG on the fjord itself.

GNL Québec, the company promoting the LNG plant, set up its offices along Talbot Boulevard, a busy commercial strip on the outskirts of town where Tim Hortons and other restaurant chains compete for business next to car dealerships and hardware stores.

Sitting in a meeting room there, the company’s president, Pat Fiore, said that “from day one” GNL Québec has been committed to listening to the concerns raised by residents.

“We’re raising the bar as high as we can.”

Fiore said for example, the company is planning measures to reduce noise pollution as tankers travel up and down the fjord, to limit their impact on marine mammals like belugas.

The plan is now to build the liquefaction plant away from the shoreline, to limit its visual impact, especially at night.

“We're using artificial intelligence to drop the lights when the employees are not in that specific area,” Fiore said.

The port

While opponents of the project argue Saguenay is no place to build a natural gas liquefaction plant, the Saguenay Port Authority takes the polar opposite view — that the fjord is the ideal place for the LNG terminal.

“It is very wide. It’s very deep — so it’s a very good navigation channel,” said Carl Laberge, the general manager of the port, located 20 kilometres east of the City of Saguenay.

At the peak of aluminum production in the 1980s, as many as 600 ships plied the fjord annually.

That number has since dipped to fewer than 250 per year, Laberge said.

Even with the arrival of Énergie Saguenay, the fjord would hardly turn into a navigational “highway,'' as opponents fear, Laberge said.

“If you did want to see a [cargo ship], you're going to wait 12 to 18 hours, sitting on your seat.”

Compared to the St. Lawrence River, where ships have to line up every day on their way to ports along the seaway, Laberge said the Saguenay port still has plenty of room to expand its operations and the expertise required to handle it.

“We think we can do it very well here in Saguenay.”

The water

Balanced in his kayak, looking out over the calm waters on another warm September morning, Mathieu Boulanger-Tessier explained why people from around the world travel to see “the giant” that is the fjord — what he calls “his office.”

Boulanger-Tessier has been a guide for seven years and the tour company’s director of operations for the past five.

After travelling around the country doing odd jobs, he settled down in L’Anse-Saint-Jean, on the south side of the fjord. He now owns a home off the grid, powered by solar panels, in the hills above the town of 1,200, with a stunning view of the bay.

“When you are paddling on the fjord, it's all pristine,” he said. “It’s all nature.”

Thirty minutes after pushing off from the beach, Boulanger-Tessier spots a harbour seal, perched on a rock on a small island.

For a few moments, he just watches. Then the tranquility is broken, when a water shuttle transporting tourists from Saguenay to L’Anse-Saint-Jean enters the bay.

The small boat’s wake scares the seal off the rock. It dives into the water, where it will have to wait until the tide rises again in six hours before hauling itself back onto dry land.

“When they feel in danger they will go back in the water,” says Boulanger-Tessier.

Three or four tankers exponentially larger than the shuttle boat would move through the fjord and past L’Anse-Saint-Jean each week if the Énergie Saguenay project proceeds, for a total of 150 to 200 ships a year.

Boulanger-Tessier wonders what impact the passage of those ships will have on his company, Fjord en Kayak, and on the safety of his customers.

“Does it mean that, as a sea kayaking company, we’ll have to stop our operations when this boat is passing?” he asks.

Boulanger-Tessier has sat down with GNL Québec promoters to hear their pitch — and their promise that the project is environmentally benign.

The company claims its natural gas will replace coal and oil in Europe and Asia, bringing down C02 emissions by 28 million tonnes per year, according to a study it commissioned.

A team of Quebec scientists has, however, challenged those figures — arguing they don’t take into account the impact of so-called “fugitive emissions” throughout the process.

“This is not the real change that we need” when it comes to solving the climate crisis, said Boulanger-Tessier.

He asks why Europe and Asia don’t move directly from oil and coal to greener technologies, such as geothermal or solar energy, instead of “transitioning” from dirty fuels to natural gas.

Unless GNL-Québec gets a firm commitment from its customers that they will ditch coal, Boulanger-Tessier doesn’t believe the project should be allowed to move ahead. And he’s skeptical such a commitment would be forthcoming.

“We’ll believe it when we see it.”

The shoreline

On the fjord’s north shore, musician David Ellis walks down a lush forest trail to the riverbank and looks out at the Port of Saguenay on the opposite shore.

Originally from Vermont, Ellis found the perfect spot to build his dream home in Saint-Fulgence, on a bay called l'Anse à Pelletier, a 30-minute motorcycle ride from his work at the Conservatoire de musique du Québec in the city.

From the back veranda of the log cabin he built with his partner, a Montrealer, he’ll have a front row seat to witness the LNG plant carved out of the boreal forest if the project goes ahead.

Ellis says it’s a challenge to keep tabs on that project as well as others brewing, including the third port, the Arianne phosphate mine and another mining project, Metal Black Rocks, that would exploit deposits of iron and titanium.

The debate over what’s best for the Saguenay has been difficult to manoeuvre for locals, he said. Everyone has friends and acquaintances who are for and against. And what information is out there is sparse — and conflicting.

"There are people in the region that are [in favour of] development but are questioning the kind of development, or [if there are] other opportunities for development,” Ellis said.

Citizen committees have formed in most towns along the fjord, as residents try to make sense of the slew of data that changes as the companies refine their pitches.

Gazoduq, the company promoting the Ontario-Quebec pipeline extension, hopes to submit its preferred route and environmental and social impact study by the end of this year or early 2020.

GNL Québec, in charge of the LNG plant itself, is now reviewing its preliminary study before re-submitting the project to federal and Quebec agencies for another look.

Like many, Ellis questions why the government review agencies are examining the pipeline and the natural gas liquefaction plant separately, since one can’t exist without the other.

“I think it’s very confusing for the normal person, the normal citizen, to understand how that could even happen,” Ellis said.

Ellis said he recognizes that it’s Saguenay’s industrial past that has allowed other sectors in the region, including culture and tourism, to flourish.

But as he looks out at the pristine mountain range with its untouched crown of trees, he can’t help but marvel at the beauty.

“We’d love to keep it that way.”