June 17, 2021

Huddled together, hands outstretched to a flickering campfire, a small group of activists dedicated to protecting old-growth forests marvel at the sinking glory of the setting sun. They are the occupants of Ridge Camp, located at the headwaters of Fairy Creek on southwestern Vancouver Island.

The camp is the original and most remote in a series of blockades obstructing old-growth logging in the area — and it is the last stand stopping industry from building roads into the unlogged Fairy Creek watershed.

Some of the activists have known each other for months; others are new. All break bread together as they are serenaded by a sweet, mournful banjo played by a man known only as Blue. The wind whips around their small, ridge-top gathering, and the sounds of their laughter mix with the music before wafting out across the rolling hills and down to the sea.

Driving into the hills behind activist lines, you could be forgiven for thinking you’d been transported to a dystopian landscape. Every few steps, for kilometres, there are piles of rocks, mounds of debris, makeshift campsites and abandoned cars waiting to be rolled into place to block the road. The people who pass by work in small crews reinforcing their embattlements, their sweat-stained faces full of suspicion, worry and resolve.

For many, news on June 9 that the British Columbia government has agreed to defer logging at Fairy Creek for two years falls flat. Activists say their blockades are about more than one watershed and that the limited protections granted to Fairy Creek, as a result of lobbying by three Vancouver Island First Nations, don't go far enough to stop the encroachment of industry via road building.

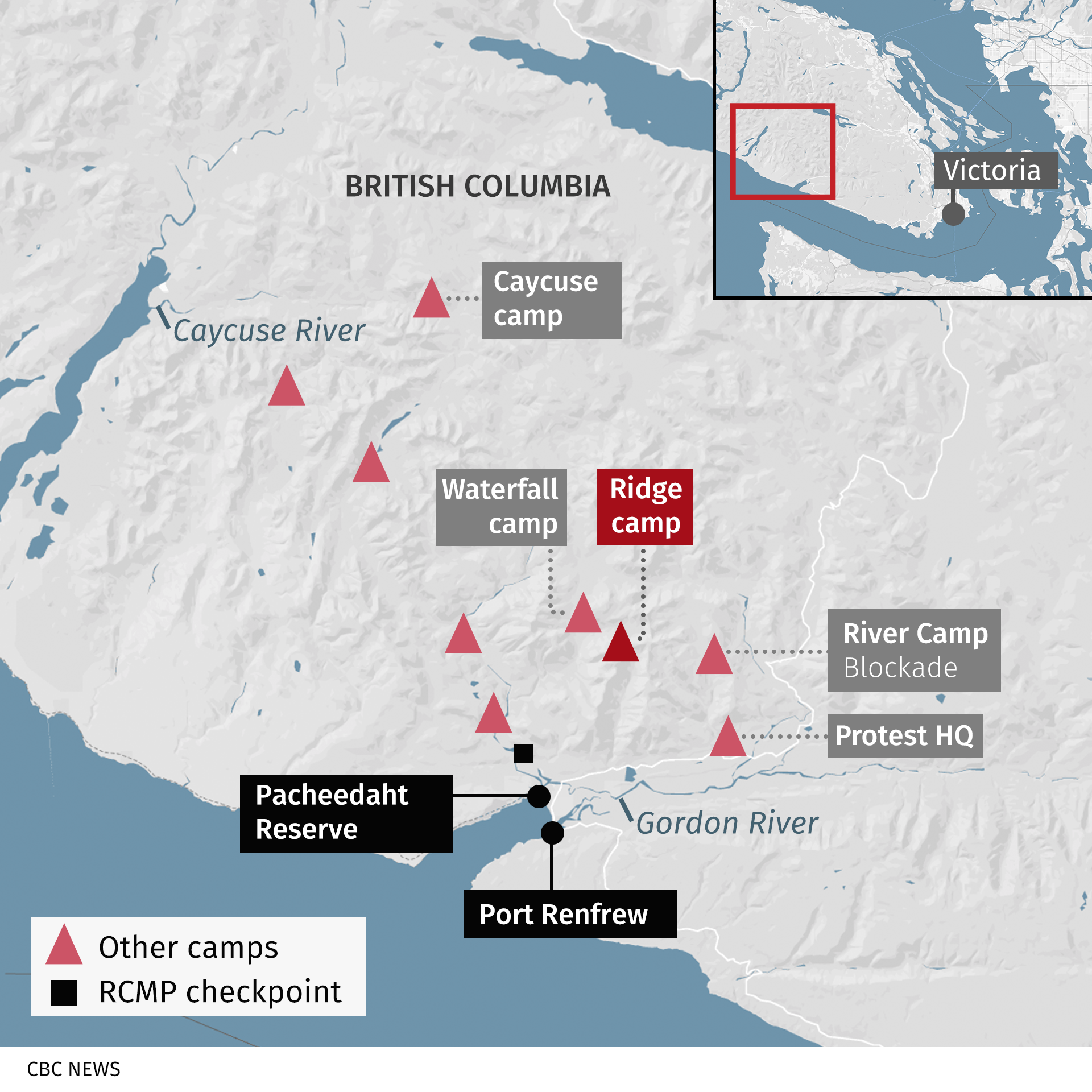

From humble beginnings nearly a year ago, what was once one camp became three: Ridge Camp, blocking Surrey, B.C.-based logging company Teal-Jones Group from constructing a road into the Fairy Creek watershed; River Camp, flanking the east; and Waterfall camp, cutting off access from the west.

In time, they grew — again and again — adding protest headquarters and the Eden Grove blockade, as well as expanding to the Caycuse Valley and beyond.

The sprawling guerilla insurgency has paralyzed logging activities in the area for months and instigated a four-week-long cat-and-mouse game between the Rainforest Flying Squad, a loose organization of volunteers that has been spearheading the protests, and the RCMP, which is trying to enforce a civil injunction to clear the blockades, which was sought by Teal-Jones and granted by the British Columbia Supreme Court on April 1.

Decades-old battle over B.C.'s forests

At the centre of the conflict is the untouched, undeveloped and nearly inaccessible Fairy Creek watershed, located in the heart of Tree Farm Licence 46. Teal-Jones wants to build a road along the upper ridge of the valley, crossing and disrupting several of the modest tributaries of Fairy Creek itself. Activists argue that building the road, let alone logging the headwaters, will irrevocably damage the valley's rare, virgin ecosystem.

The efforts of activists stretch beyond Fairy Creek and are part of a larger battle around forestry in B.C. that has been taking place over the last three decades. Examples include an investigation into logging plans in the Nahmint Valley that led the province's Forest Practices Board to issue a report last month finding a failure to comply with laws protecting old-growth forests and biodiversity values in some ecosystems. The War in the Woods protests, culminating in 1993, helped save Clayoquot Sound from clearcutting.

But while some progress has been made, activists say it's come too slowly.

At Fairy Creek, police and activists have scrambled feverishly for weeks to stay one step ahead of each other. The shifting tactics of both sides have included feints and counterattacks, calculated delays and deception — all the while performing reconnaissance on each other before regrouping and re-engaging.

The activists have used a variety of "hard blocks," including cementing PVC pipes to the road and locking their arms to the ground. Police have used heavy equipment, such as jackhammers and excavators, to dig out protesters. So far, more than 200 arrests have been made.

Fairy Creek's stands of yellow cedar and hemlock date back hundreds, possibly thousands of years. At night in the old growth, the silence wraps around the ancient trees like a soft blanket, broken only by the melodic hooting of owls. Daybreak arrives with a chattering of warblers, robins and thrush.

Tucked away among the yellow cedar is the Ridge Camp. The activists pitched their encampment in the middle of a line of trees that had been felled for road building, just down the hill from the ridge-top lookout.

The camp consists of a smattering of tents dotting the forest, along with a kitchen area and a fire pit, all covered by an intricate series of tarps tied to ancient trees. High up in the canopy, obscured from view, hang a series of tree-sits, at least six, each occupied by activists determined to not let a single other tree be cut down.

The value and scarcity of old-growth forest and how best to preserve it remains a hotly debated topic in B.C. The provincial government considers a coastal forest old growth if it has trees older than 250 years while some types of Interior forests are old growth if they have trees more than 140 years old.

Compared to second-growth (often monoculture forests replanted after logging), old-growth stands are more diverse. A result of their natural progression, this manifests in greater gaps in their canopy, which leads to a broader spectrum of biodiversity in their undergrowth, including a wider collection of lichens, mosses and fungi.

Additionally, activists argue that old-growth forests play an outsized role in carbon sequestration — and indeed, scientists have found that some trees and their ecosystems appear to be more effective than others over time when it comes to carbon capture.

Entrepreneur turned activist

Ridge Camp is the heart of the resistance — and at the heart of the camp is a mother of two and cancer survivor.

Shawna Knight, 43, who is also an entrepreneur and a longtime West Coast fixture, and her children would regularly visit the forests near Port Renfrew to admire the tall trees and "get their tan on" at the local lakes and hidden river swimming holes. In August 2020, when a group of old-growth activists saw satellite imagery of logging roads being built into Fairy Creek, she knew she had to join the planned blockade.

Knight quickly became one of the most active and fervent supporters of the movement, selling her food-truck business and moving first into a bus at Waterfall Camp and now, a tree-sit at Ridge Camp.

"After my last surgery, I came out to the blockade three weeks later and decided this would be a good place for me to learn and heal," she said.

"In Tree Farm Licence 46, there are two years of old-growth logging left, and then, what will we do? If this is going to be gone in two years, why not figure it out now?"

Knight is of mixed Norwegian and Secwepemc heritage. Her maternal grandmother attended residential school in British Columbia's Interior, but she has lived most of her life estranged from the Indigenous part of her identity.

"This whole thing has been a reconciliation in ways for me personally," Knight said. "I'm learning things, where I'm from, where I belong and what my obligations and responsibilities are."

First Nations on both sides

Of particular importance for Knight is the relationship she has built with Bill Jones (no relation to logging company Teal-Jones), an elder with the Pacheedaht First Nation, whose territory includes Fairy Creek and Walbran Valley, another old-growth area threatened by logging.

An ardent supporter of the blockades since their early days, Jones has become a figurehead for the movement and the symbolic leader of the Rainforest Flying Squad.

His outspoken position that old-growth logging in his territory should be halted stands in sharp contrast to the relative silence from other members of his First Nation and in direct opposition to demands made by the community's elected chief, Jeff Jones.

The chief has repeatedly asked for "third-party activists" to end their blockades and respect his authority and the band council's decision to enter into a revenue-sharing agreement with the B.C. government that allows the band to share in the stumpage payments the province receives from Teal-Jones.

In a phone interview with CBC News on June 7, Bill Jones said he has invited the protesters to Pacheedaht territory and that the elected chief does not speak for all Pacheedaht.

"The federal government set this political system up on reserves that entrenched an unfair band council and disenfranchised the band membership by not giving them any input into band council governance," he said.

Under the federal Indian Act, in order to receive funding, First Nations are required to have a band council and an elected chief that conform to the structure laid out in the legislation, with a setup similar to a municipal mayor and council. Jones and others say these Indian Act structures do not reflect traditional First Nations governance structures.

"Calling our leaders chiefs was a patronizing ploy on the part of Indian Affairs," Bill Jones said.

"My mother told me that in her childhood, we didn't have chiefs. We had elders and heads of families. Governance was more familial than it was hierarchical."

He insists that Pacheedaht members have never been consulted on the decisions made by Jeff Jones, including signing what Bill Jones calls a "crippling contract" between the First Nation, Teal-Jones and the provincial government that greenlit old-growth harvesting while also barring Pacheedaht members from interfering with provincially authorized forest activities on their land.

Jeff Jones was not available for comment.

Across the province, several First Nations have recently called for a halt to old-growth logging in their traditional territory, including the Kwakiutl on north Vancouver Island, the Nuxalk on the central coast and the Squamish in the Lower Mainland, while other First Nations, such as the Huu-ay-aht on southern Vancouver Island, have been expanding their participation in the logging industry.

Bill Jones and the Rainforest Flying Squad have refused to acquiesce wholesale to the authority of the band council, but that doesn't mean they aren't willing to sit down with Chief Jeff Jones to find common ground. In fact, they say, they have been waiting to do just that.

The opportunity presented itself on June 8. In the early afternoon, Knight and two other senior members of the squad who go by the names Karst and Moe received a radio transmission from one of the lower camps.

"We just got word that Chief Jeff Jones wants to meet with Rainforest Flying Squad and Bill Jones at HQ tonight," Knight relayed, the excitement in her voice palpable.

"Oh my God! Is there anyone there who can represent us capably?" Karst asked.

A long beat of silence passed between the two.

"We can hike out," Knight suggested.

"OK, let's go."

The day before, three First Nations — the Huu-ay-aht, Ditidaht and Pacheedaht — released a declaration calling for limited deferment of old-growth logging. The time seemed right for compromise, so Knight, Karst and Moe headed down the mountain in high spirits.

They left behind a cadre of supporters tasked with improving camp infrastructure and installing new hard blocks. It was agreed the crew would be setting up a new suspended tree-sit to help block further road building.

'It had to happen'

Jean-François Savard is one of those who stayed behind. The carpenter from Jordan River, on Vancouver Island, has been at the blockades for more than two months. He joined the movement after the court injunction was granted on April 1.

"It's unfortunate we have to be in this position to perform civil disobedience and block industry," Savard said while scouting for the location of their new tree-sit.

"But it had to happen, right? Otherwise, there'd be a lot more trees down now as we speak."

Savard moved to the West Coast years ago and worked as a commercial fisherman. But he saw the industry decline and as a result, made the decision to shift careers. Now, he is perplexed with the forestry industry's continued focus on old growth and its inability to see the writing on the wall.

"In a few years, if all this old growth gets cut down, those people won't have any work," he said.

"I understand that people need to feed their families, but it is very short-sighted to not see that resources are dwindling down to nothing, and shortly, people will have to find new jobs anyway."

In a statement on June 14, representatives for Teal-Jones said the company expects to continue harvesting in Tree Farm Licence 46 for decades.

The forest sector accounts for more than a quarter of B.C.'s total exports. It brought in $11.9 billion in 2019 and employs more than 50,000 British Columbians. The B.C. Council of Forest Industries estimates that 38,000 direct, indirect and induced jobs depend on logging old growth.

To Savard's mind, it is incumbent on the government and society at large to act now to help the forestry industry shift to more sustainable harvest practices. But, he said, since the government refuses to take action in time to save what little old growth is left, he will.

Shimmying up an ancient cedar with no safety line, Savard and another activist tie off a series of rope anchors from which they will hang their new tree-sit. Below, the remaining activists work hurriedly to construct a platform on site using two-by-fours and plywood flown into the camp by a rogue helicopter pilot.

What next?

There was a brief pause in the work when it was announced on June 9 that, following the declaration made by the Huu-ay-aht, Ditidaht and Pacheedaht, B.C. Premier John Horgan had decided that logging in the Fairy Creek watershed would be deferred for two years. Teal-Jones had also previously agreed to abide by the wishes laid out in the declaration and was quick to point out that the document also explicitly asks for all other logging activities to go forward.

"Are they stopping road building as well?" Savard asked from his lofty perch.

"Not clear," was the answer.

With a collective shrug, the activists returned to their work hoisting the new blockade platform into the treetops.

At dinner, there was a sense of accomplishment, and news came on the radio that police had been repelled for the day from Waterfall Camp. But the elation was met by the sombre return of Knight and Moe.

"What happened at the meeting?" asked their fellow activists.

"It was nothing," Moe said.

The limited communications between camps had resulted in a version of the children's game telephone, in which one person whispers a message into another's ear until the message returns to the original teller completely transformed. In this case, a representative from the Pacheedaht First Nation delivering a written copy of the recent declaration had morphed into a request for a meeting from the elected chief.

"We don't negotiate with colonizers," Knight said in an attempt to save face and lighten the mood.

"The only thing left to do is get back in our trees."

As night fell, the camp and its inhabitants were left hanging — along with the question of how long they would be able to keep up the fight and what will ultimately be accomplished.