November 3, 2021

This story contains details readers may find disturbing, and discusses suicide and sexual assault.

They must have looked an odd sight, the two of them.

A 14-year-old boy decked out in tails, strolling around with an Anglican minister in full priestly regalia.

It was the late 1970s, on New Year's Day.

The boy, Glenn Johnson, and the priest, Wayne Hankey, were wandering the streets of downtown Halifax together, attending the New Year's levees.

It should have been a celebration, a chance to take in the promise of a new beginning.

But for the boy, it was anything but auspicious.

Some of the memories of what happened on that trip to Halifax got buried deep in Johnson's mind. It wasn't until this February that those memories surfaced, quickly and violently.

"I wanted to kill myself that instant and very nearly did," Johnson said in an interview from a hospital in Ottawa, where he is receiving treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder and depression.

"This is as real to me now as it was back then."

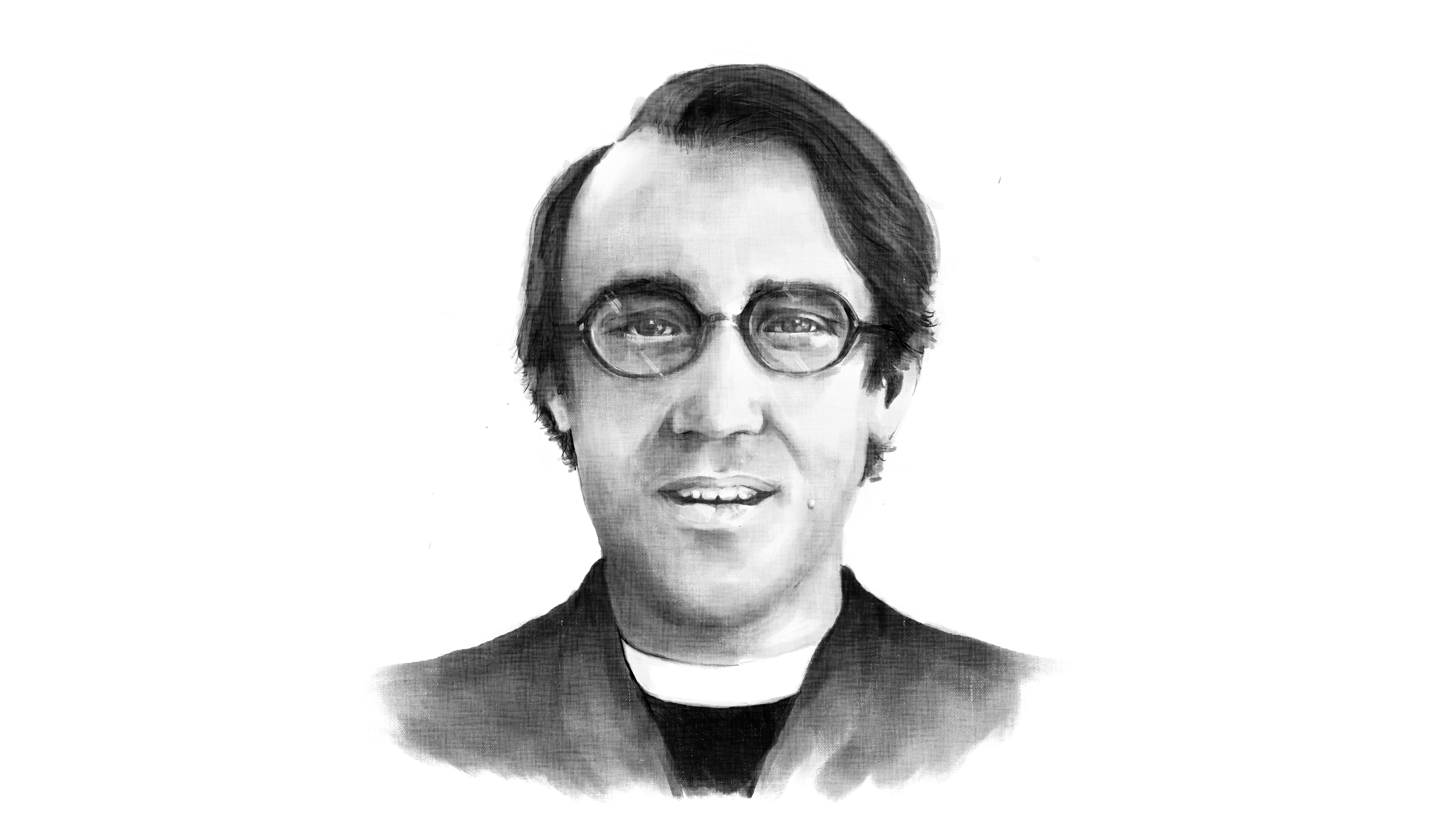

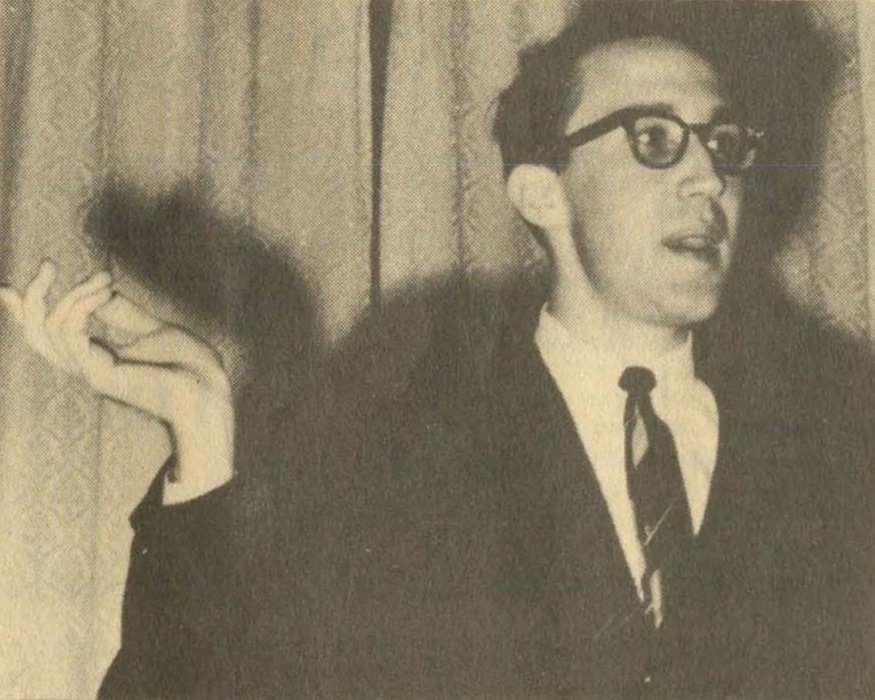

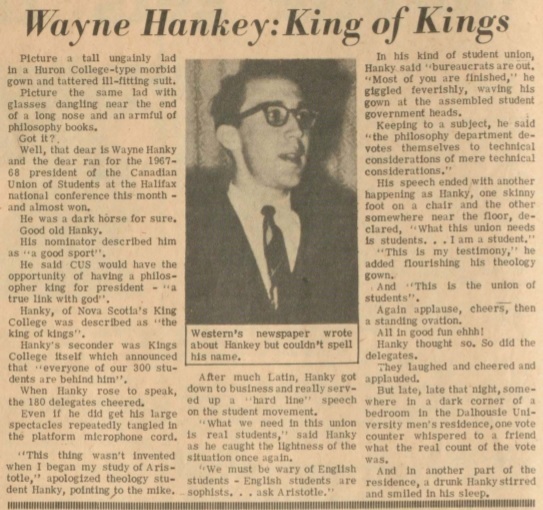

Hankey wasn't simply a priest — he was by this time a central figure on the University of King's College campus, a small liberal arts school in south-end Halifax.

Over the course of more than 50 years, many of them teaching philosophy, classics and theology until his retirement in 2015, he asserted his presence and carved out his legacy.

The Oxford-educated professor, who came from a modest upbringing in Lower Sackville, N.S., would become as familiar and integral to the world of King's as the stones and pillars of its buildings.

His charisma was epic, according to former students, though he could be ruthlessly critical. His intellect would make him the academic inspiration to generations of ambitious students.

But he also left in his wake lives that were forever changed for the worse.

While rumours and stories of Hankey's misdeeds have swirled on campus for decades, knowledge of some allegations of abuse has been confined to tight circles that are only now loosening.

In February and April this year, Hankey, now 76, was charged with sexual assault, indecent assault and gross indecency for incidents involving three different complainants between 1977 and 1988, including some alleged to have occurred on the King's campus.

He has pleaded not guilty in each case.

The CBC sent a letter to Hankey's lawyer, Stan MacDonald, outlining the allegations it planned to publish in this story. MacDonald said many of the allegations are "untrue and inaccurate," but that his client is "in the midst of court proceedings and is unable to comment specifically on allegations against him at this time."

The criminal charges have left many connected to the university questioning what exactly administrators knew at the time, and what, if anything, they did in response.

The stories continue to emerge.

If you have information to share about this story, contact reporter Frances Willick at frances.willick@cbc.ca

Chapter 1: At the President's Lodge

Chapter 3: The boy in the pool

At the President's Lodge

Johnson's horrifying memories returned suddenly one day early this year after he read a news article about the first charge laid against Hankey.

In the 1970s, he had been a kid from East Port Medway, a small coastal community about 130 kilometres southwest of Halifax. His parents weren't particularly religious, but his grandparents were, and he was thinking about becoming an Anglican minister.

His parish priest, Wayne Lynch, had introduced the young altar boy to Hankey, a professor and the director of an academic program at King's called the Foundation Year Program (FYP), which taught the underpinnings of Western philosophical and political thought.

Johnson was still a bit young to be considering his post-secondary education, but Hankey had told him about the program and he was interested.

So when the two priests came to his parents' house to ask their permission to take him to Halifax for a few days over the Christmas holidays to show him around campus, they didn't blink an eye.

"My parents thinking … what could be wrong? We have people in authority, we have people who are in a trust position with the family," Johnson said.

Johnson's parents didn't know that Lynch was far from trustworthy. Their son hadn't told them that he'd previously been assaulted by Lynch.

He would remain silent, too, about what Hankey allegedly did to him on that trip to Halifax.

Here's a poor kid from a fishing community staying in a mansion where there's free-flowing wine and booze — even for a 14-year-old.

Johnson believes he spent three nights in Halifax in late 1977/early 1978, staying with the two priests at the President's Lodge at King's, where the president of the university traditionally makes his home.

He said he's not sure where the president at the time, John Godfrey, was, or how Hankey got the keys to the house, which is located on a corner of the campus.

He remembers the colonial-style painting above the fireplace in the bedroom, the grandfather clock near the staircase downstairs, the big kitchen.

He remembers listening to music on an "amazing" stereo, and a bright sunroom that stretched from one end of the lodge to the other.

To Johnson, it seemed opulent. He was dazzled.

"Here's a poor kid from a fishing community staying in a mansion where there's free-flowing wine and booze — even for a 14-year-old."

Johnson said the priests got him drunk on wine and gin, and one night he woke up to find that his underwear were off and he didn't know why.

Another night, he said, he awoke to find Hankey in bed with him, assaulting him orally. Johnson said it was dark in the room, but he knew it was Hankey because he recognized his voice.

"I didn't know what to do," said Johnson. "I froze. I was really confused. I didn't know, like, is this something I'm expected to do in order to get into King's? Is this what you have to do when you want to be a priest?"

Many years later, in 1999, Lynch would plead guilty to sexually abusing Johnson, and was sentenced to house arrest for two years. Johnson's civil suit against Lynch and the Anglican Church was settled out of court in 2000.

Johnson is not one of the three complainants in the criminal cases involving Hankey now before the court. He contacted police, but they decided in June not to lay charges. Johnson said police told him that because he mixed up the names of Wayne Lynch and Wayne Hankey one time in his written statement, his credibility would be disputed in court.

A spokesperson for the Halifax Regional Police would not explain why no charge was laid, saying that in order to protect the privacy and well-being of sexual assault victims, police do not provide any information about investigations.

Johnson said if his case had moved forward, he would have requested that a publication ban on his name be lifted. He also requested that the CBC use his name for this story.

"I don't want people to feel that there's a stigma surrounding this, because it is not our fault," he said.

Stephen Lindsay, a psychology professor at the University of Victoria who studies memory and conscious experience, said if a person avoids thinking about an experience, or avoids cues that could trigger memories of that experience, they can develop a habit of not remembering the event.

"It is possible for somebody to have had a seemingly very memorable, important, dramatic event and not remember it," Lindsay said.

Highly distinctive cues, such as being in a specific place or seeing a photo, can bring those memories back.

Lindsay said people can also have false memories, wrongly believing something happened when it didn't.

"But I think normal people are unlikely in response to ... a normal cue like that to have a qualitatively false memory. I think that's quite rare."

Johnson didn't end up going to King's. He didn't want to be assaulted again.

Instead, he studied journalism at Holland College in Charlottetown and built a career in newsrooms from Nova Scotia to Manitoba, culminating in a senior news position at Postmedia.

He left the industry in 2011, and was working at a software company in Ottawa until he went into the hospital after remembering the incident with Hankey.

He feels King's has some culpability.

"Here is a guy who was out there soliciting potential people for King's — or saying he was…. He told me I'd be a shoo-in ... and he assured me that I'd be able to get into it because of him."

Johnson has contacted lawyers to discuss filing a civil case against Hankey and King's.

"I hope that King's will acknowledge that they had a predator. They may not have understood he was a predator, but they're responsible for it, because they had to hear stories throughout the years."

When news of the first criminal charge against Hankey broke on Feb. 1, King's immediately announced it would conduct an independent review of the allegation. The university has hired two Toronto lawyers to determine the facts of any allegations, to decide whether King's acted to ensure the safety of students and to make recommendations on how King's should respond.

The university has declined interview requests, saying it wants to respect the independent review and criminal justice process.

Johnson spent much of this summer whiling away the time in the hospital, occasionally watching movies or veterinary shows on TV or reading Monty Python books, the only reading material he could focus on.

After being interviewed by the CBC, Johnson underwent electroconvulsive therapy to treat severe depression. He returned home in early September, but was readmitted to hospital a few weeks later.

Nightmares, he said, haunt his sleep.

He sees Hankey coming down the hospital hallway toward him.

He wakes up.

He leaves his room, wanders the halls, looks for a nurse, but there's no one there.

He wakes again.

A dream within a dream.

"I was stuck with nowhere to go and nobody to help me," he said. "They can't give you pills that are going to fix this and take it away. So I'll carry this with me to the grave."

If you are thinking of suicide or know someone who is, help is available nationwide by calling the Canada Suicide Prevention Service toll-free at 1-833-456-4566, 24 hours a day, or texting 45645. (The text service is available from 4 p.m. to midnight ET).

If you or someone you know has experienced sexual assault, there are several resources available to help.

If you feel your mental health or the mental health of a loved one is at risk of an immediate crisis, call 911.

The virtuoso

The cassette starts rolling.

Tendrils of sound, gentle piano notes, spread through the church. Then his voice begins, deep and full.

The world can be a lonely place

Without a warm familiar face...

There are goosebumps and tears among those gathered in the pews for their friend's funeral as they hear his voice, as if from the beyond.

This is, as it were, Richard March's curtain call.

Remember every fond embrace

There's a tiny crack in his voice — one that wouldn't have been there a few years ago, before he got sick.

And keep me close to you.

March was, by all accounts, something of a musical prodigy.

As a kid, one day he decided he wanted to learn how to read music. "A week later, he could read it," said his brother Peter March.

Soon after, Richard's bedroom was full of file folders of musical scores. At about 13, he got himself a music stand and conductor's baton, and would enthusiastically direct a room full of imaginary musicians.

In high school, Richard created the Waegwoltic Chamber Ensemble, a rotating cast of his high school friends and other kids he knew from the Halifax All-City Music Program. Woodwinds, strings — whoever was free on a given weekend afternoon — would gather at the March family home in south-end Halifax and play chamber music together.

The ensemble played publicly a couple of times, including at concerts in the community of Crousetown on the province's South Shore.

After he graduated from Queen Elizabeth High School, Richard started the Foundation Year Program at King's. Though his brother Peter said Richard's personality wasn't very suited to the program, it made sense in some ways. Richard was always up for a challenge — plus, the director of the program, Wayne Hankey, was well known to the family.

Peter almost calls Hankey a family friend, but he stops short. He wasn't, quite.

The March family was a churchgoing family. On Sundays, parents Bill and Barb and their children would head to the cathedral downtown for mass, where Bill would belt out the hymns. Afterward, the kids would hang around while their parents drank bad coffee in the church hall and chatted with priests and other parishioners. Socializing would often spill over into the afternoon at one house or another.

"It wasn't weird or odd in our upbringing to have people — ministers, priests, people from the church — sort of dropping in for social occasions. It was sort of built into the way we were brought up," said Peter.

Hankey, he said, had a knack for insinuating himself, trying to "engineer himself as a friend of the family." He would show up on a Sunday morning with a newspaper, sit in a chair in the backyard and expect to be invited for breakfast or lunch.

He had a way of fobbing off the awkwardness on his seeming eccentricity, Peter said.

"He cultivates this sort of, you know, a donnish or British intellectual divine person, right? And so he was sort of a little exotic."

In retrospect, Peter said, "it's like the premise of a horror movie. You can see it coming."

Almost 50 years after the fact, Peter and his four remaining siblings are uncertain about the precise circumstances of how and where Hankey sexually assaulted Richard.

Most of the siblings knew something — bits and pieces gleaned over the years from conversations with Richard or their parents, who have all died.

They got together on a recent Zoom call to pool their knowledge and talk about it for the first time.

They know it happened in 1973 or 1974, when Richard was 17. They know it happened during a concert series in Crousetown, near the small community of Petite-Rivière, where Hankey had been appointed priest-in-charge of the parish. They know Hankey and another priest, Wayne Lynch, got Richard drunk on gin.

'He looked bad, but he looked like he was not spiralling down a hole, but just sort of deeply, deeply hurt and trying to regain some equilibrium or, you know, get over a trauma.'

Initially, Richard clammed up. But eventually, he told his parents what happened.

He became depressed and was admitted to hospital to receive psychiatric care. Peter remembers visiting him while he was there, and Richard told him, in vague terms, what had happened.

"He looked bad, but he looked like he was not spiralling down a hole, but just sort of deeply, deeply hurt and trying to regain some equilibrium or, you know, get over a trauma."

Virginia Beaton, a high school friend who played in Richard's ensemble, said she heard about the assault from a mutual friend at the time.

"He had always been very, you know, light-hearted, energetic, happy — you know, a performer. It seemed to really shake him."

The CBC has spoken with one other person who independently knew of the assault. Hankey has never been charged.

Within a month or two, Richard more or less became himself again — funny, gregarious, exuberant. He left King's and eventually graduated from Dalhousie University.

Richard chased life to Toronto and then Stratford, Ont., where he became a regular on stage at the Stratford Festival.

In 1985, Marion Adler was an aspiring musical theatre actress who dropped in on a late-night cabaret when Richard happened to be performing Donizetti's Sonata for Flute and Piano — only he had adapted it for vacuum cleaner and piano, using his lips to make the sound of a vacuum cleaner.

"It was an incredible feat of humour and virtuosity at the same time, because it was just ridiculous," she said. "And I looked at him and I thought, 'I am coming to this theatre company and I'm going to work with that guy.' I was so, just, besotted."

She got her wish. Adler and Richard — a "blazing light" of a creative partner — became dear friends and artistic collaborators.

Richard became a well-known figure in Stratford, not just in the acting world, but in the community, too. He'd play bingo with the locals on Sunday afternoons, and couldn't walk down the street without someone — a mechanic or a shop owner — stopping him for a chat.

At the time, in the late 1980s, the "townies" were suspicious of theatre folk, Adler said, and many were homophobic, too. Richard won everyone over and became the de facto ambassador for the festival and the gay community, earning the nickname "the mayor of Stratford."

'So our whole relationship was about living in exactly that moment. He would talk about the past, but not very much, and so I really don't know his back story.'

Adler knew something was seriously wrong when Richard started to hem and haw about going to New York City to perform in a role she and her husband had written for him.

It started out as a cough. Gerry Valentino, Richard's partner at the time, said soon afterward, Richard had full-blown AIDS.

"So our whole relationship was about living in exactly that moment," Valentino said in an interview. "He would talk about the past, but not very much, and so I really don't know his back story."

Neither Valentino nor Adler recall Richard talking about being assaulted as a youth. For all his extroverted effervescence, this was something he didn't discuss.

Richard had a "tonne-of-bricks type of personality," said his brother Peter.

"So, not a shrinking violet. So, he may have been able to absorb an experience like this without having it crush him. It didn't crush him," he said.

"We're completely convinced that it scarred him…. It hurt him and it stayed with him for the rest of his life."

As Richard's days dwindled, he put his energy into one final performance in Stratford that was recorded on a cassette called Ricardo Live.

The benefit concert for a local AIDS counselling and support program would also serve as his goodbye to the community that watched him grow as a performer and nurtured him through his illness. Four hundred people packed into a rehearsal hall that night to hear him play.

Six months later, in March 1992, many of those same people gathered again for Richard’s funeral in Stratford.

The cassette rolls and he sings his farewell.

Don't cry my love you'll be all right

I'll stay the whole night through.

Sweet dreams my love till morning light

And keep me close to you.

Neither Richard March nor Glenn Johnson told the University of King's College about what happened.

But other incidents did come to the school's attention over the years that followed.

The boy in the pool

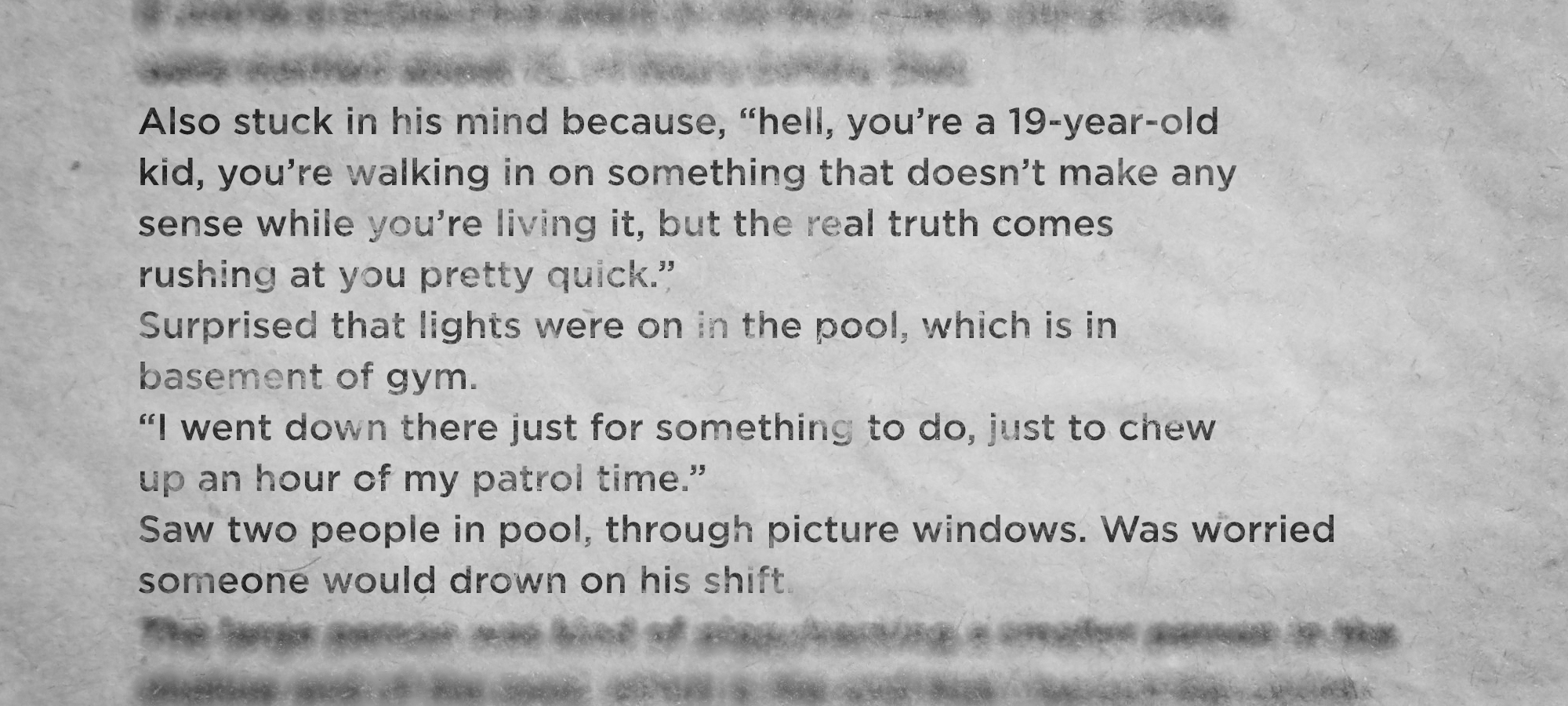

The date was memorable, at least to the sole known witness of the incident.

It was July 29, 1981, at 10:22 p.m.

"The reason that sticks in my mind is, if you're a monarchist you'll know that Charles and Di were married about 13, 14 hours before that," Dave Beed later recalled.

Beed was a student and a campus police officer at the University of King's College that summer. His recollections of the incident were documented in an interview with a retired RCMP officer who was investigating Hankey for the Anglican Church about 10 years later.

The CBC has obtained a copy of the investigator's notes from his interview with Beed.

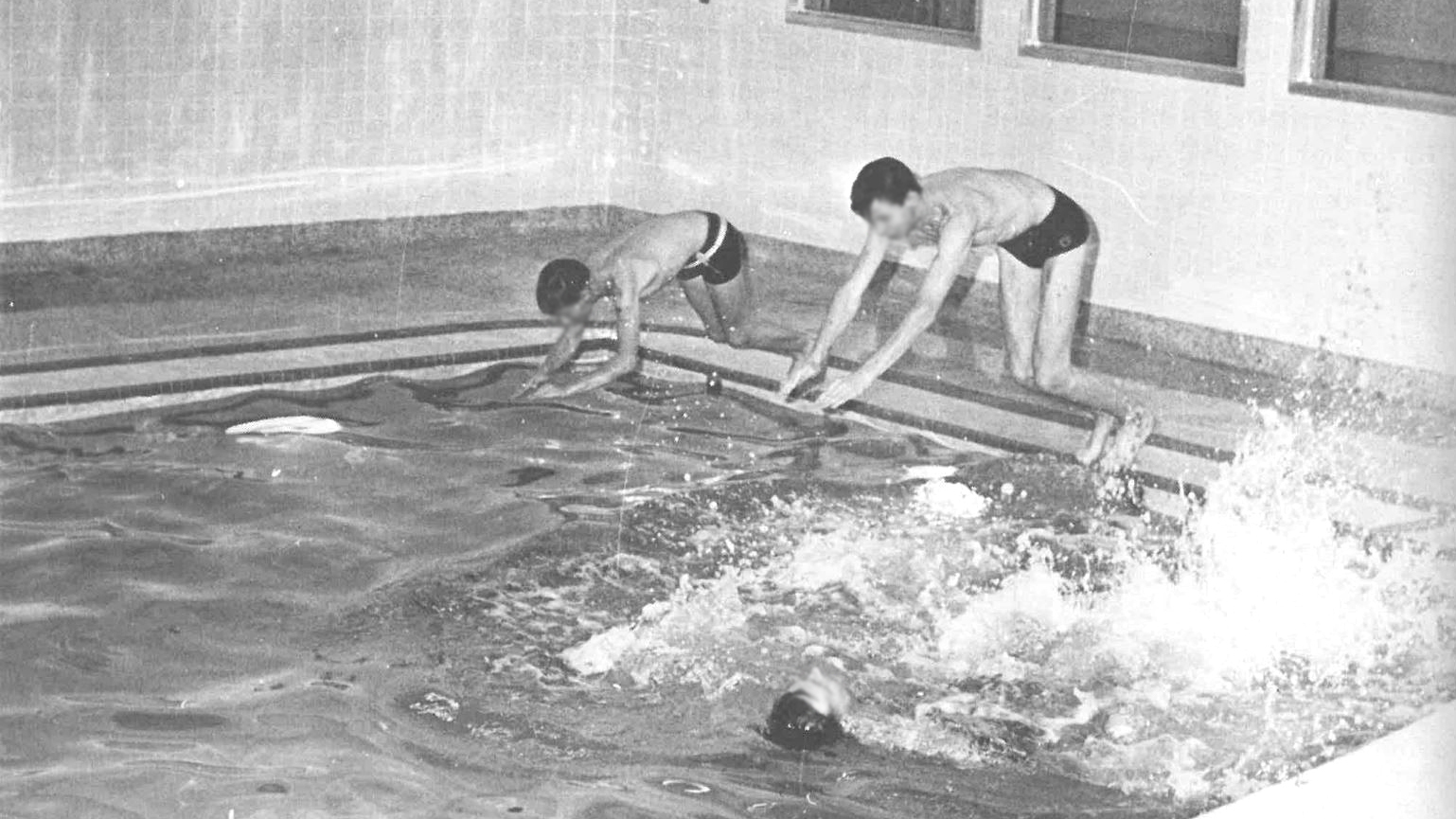

The notes say Beed was making his rounds that night when he saw the lights on in the pool at King's.

Through the windows, he saw a large person "kind of piggybacking" a smaller person in the shallow end.

By the time he opened the door into the pool area, the two people had separated, with the larger person swimming to the deep end and the smaller person, a boy, climbing up onto the pool deck.

"This kid's looking up at me, absolutely terrified, crouched nude, totally nude," the interview notes say.

Beed told the investigator the boy was "definitely a minor" because of his size, and guessed he was 12 or 13 years old.

The larger person eventually swam over and Beed recognized him as Hankey, who was an assistant professor.

"I remember saying to myself, 'You son of a bitch.'

"He was totally nude, hanging onto the ladder, totally lost for words, and if you've ever talked to the man, he's not a man lost for words."

Beed told Hankey to let him know when he'd locked the pool, and left.

Later that evening, Hankey appeared in the campus police office and told him he had a bad case of gout and that his doctor had recommended swimming. He did not offer an explanation for the boy's presence, and Beed later wondered if Hankey believed he hadn't seen the boy.

Beed wrote in the campus police logbook, "discovered or found Rev. Hankey with male friend swimming nude in the pool."

But the next time he was on duty, that page was missing.

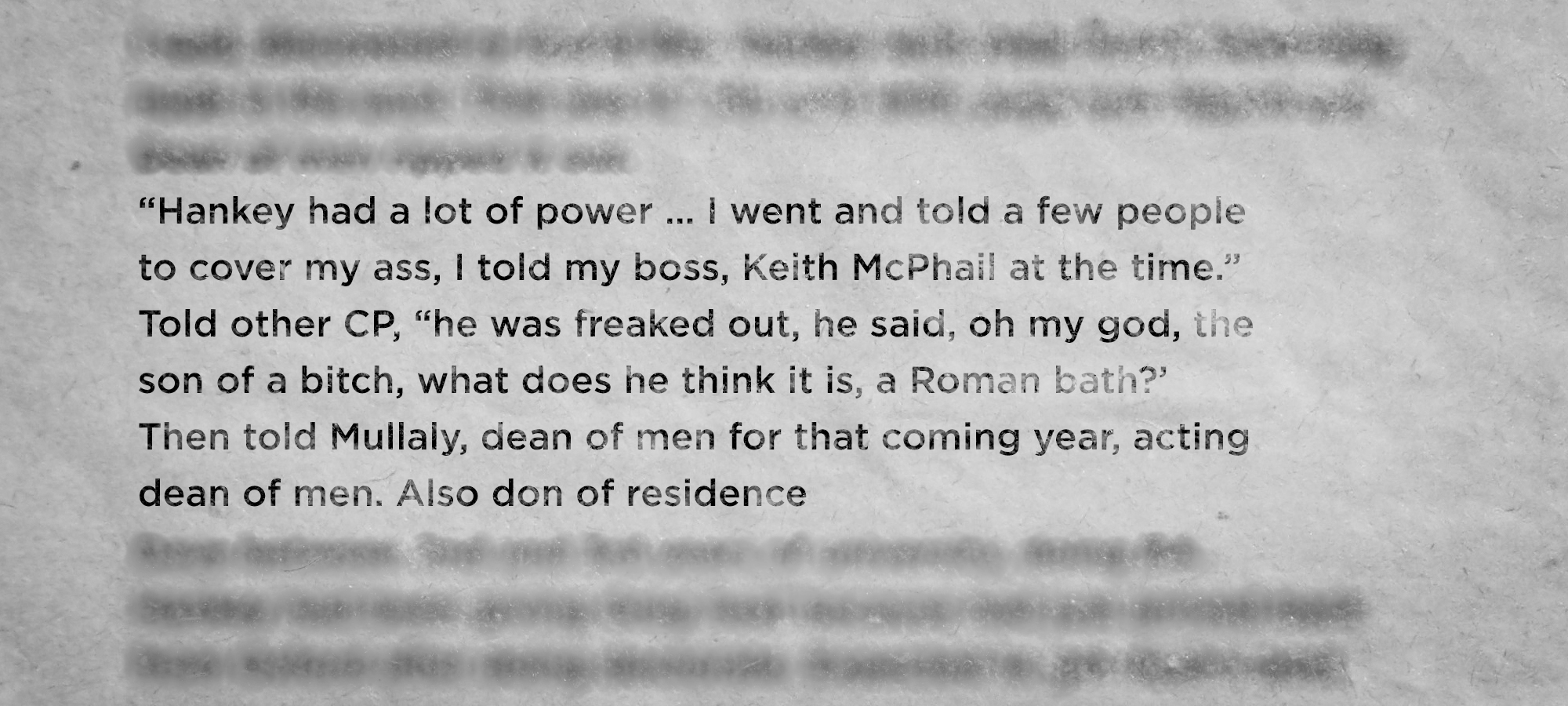

The investigator's notes say Beed told his boss, Keith MacPhail, about what he saw in the pool as well as Greg Mulally, who was dean of men and don of residence at the time.

Word spread quickly, including to adjacent Dalhousie University, where Hankey would also teach classics for many years, including after his formal retirement.

"Found out a week later the entire Dal Faculty Club knew of it," the notes say.

Mullaly, now a retired lawyer living in B.C., said he remembers Beed reporting he'd seen Hankey and an "underaged male who wasn't a student" swimming naked in the pool together.

Mullaly said he remembers telling a more senior staff member at the university about the incident, and, though he doesn't clearly remember who that person was, he believes it was either Henry Roper, the registrar at the time, or possibly Colin Starnes, who was the director of the Foundation Year Program.

Reached by phone at the end of May, Roper said, "I have absolutely no comment" and hung up the phone.

Starnes told the CBC he never heard of any misconduct allegations against Hankey before a later 1990 allegation that led to Hankey being disciplined by the school.

A Chronicle Herald story published earlier this year said when the president of King's at the time, John Godfrey, learned of the incident in the pool, he asked a senior administrator to speak with Hankey and report back.

The administrator, who was not named in the Herald story, said Hankey swore to him that the incident was completely innocent, and when the administrator reported this to Godfrey, the president ended the probe and wanted no written report.

When the CBC called Godfrey at his home in Toronto in July, a woman who answered the phone said he would not answer any questions about the Hankey allegations.

Mullaly said he never heard back from administration after passing on the report.

"Nobody ever got back to me. Nobody ever said a word," he said.

Beed told the retired RCMP officer that if the school did investigate, it didn't include him — likely the only witness: "They didn't investigate at all. Nobody asked me anything."

Beed said he was afraid of being kicked out of residence, and was intimidated by Hankey, according to the notes, so he didn't report the incident to police.

"I guess I was scared being up there and standing, not only in front of Hankey, but where would the university come in? They're going to protect one of their own … get rid of the big-mouthed kid campus police guy instead of one of our own."

The priest, chastened

In late 1990, a man sat down and hand-wrote an eight-page letter addressed to the bishop of the Anglican Church in Nova Scotia, Arthur Peters.

The letter claimed that Hankey had sexually abused the man for about two years in the late 1970s, beginning when he was in his late teens.

The bishop brought a charge of immorality against Hankey, and a rare ecclesiastical court was convened to adjudicate the matter. The CBC has obtained a copy of the court's decision.

The document said the assaults took place while Hankey and the young man were swimming naked in the pool at the University of King's College.

"I felt Wayne's hand on my genitals," it said, quoting from the man's original letter to the bishop. "It was invariably in the shower that he continued to assault me either orally or manually. At no time did I protest."

'Dr. Hankey entered an inculpatory statement which in our opinion constitutes a confession of guilt to the charge or charges brought against him.'

The charge of immorality specified that Hankey initiated the acts "without invitation or verbal consent," that in doing so he sexually abused and sexually assaulted the youth and that he abused his power and breached a “duty of trust as a priest, teacher and family friend.”

During the trial Hankey pleaded not guilty. Then, according to the decision, proceedings took "a most unexpected turn."

"Dr. Hankey entered an inculpatory statement which in our opinion constitutes a confession of guilt to the charge or charges brought against him."

Hankey’s statement said he acknowledged that "sexual acts as generally described" by the complainant took place between them.

"I acknowledge and repent my fault and sin in them: first, because as sexual acts outside the marriage bond they offend the sixth commandment, but also I accept that because of the difference in age and status between [the complainant] and me, the responsibility for these sins is more heavily mine," he wrote.

The court found Hankey guilty, despite the testimony of friends and colleagues in the church, at King's and Dalhousie, and about 25 letters that were "overwhelmingly" in support of Hankey "as a priest of the Church, as a very distinguished scholar, and as a teacher and helpful friend to many."

The church stripped Hankey of his right to practise as a minister, and he was also expected to undergo spiritual and psychological counselling.

Rev. John Newton, the only surviving judge in the ecclesiastical court case, said the judges had a desire to be "utterly fair" to everybody in the case.

"But clearly, there had been a serious violation here, and there had to be discipline involved," he said.

Newton said while Hankey was well known — "whether famous or notorious is a better word, I'm not sure" — for his "large personality" and "aggressive" style, he had never heard of any allegations about him before the bishop called him one evening to be a member of the court.

"It came as a bolt out of the blue for me."

Asked whether the fact that the allegations involved two people of the same sex played a role in the finding of immorality, he said it did not.

Newton said the case was highly emotional, and people were in tears.

"I was always drained of energy when I walked away from it each day. It was intense."

The repercussions of those allegations did not stop with the Anglican Church.

The man's complaint was forwarded to King's, where Hankey was the librarian, professor in residence and associate professor of classics.

The president of the university, Marion Fry, struck a committee to investigate the allegations and the committee filed its report to her in April 1991.

That report, however, has gone missing.

The university was unable to find it when the Halifax Regional Police began asking for Hankey's employee records as part of the police investigation earlier this year.

In a letter from current president William Lahey to the King's community this March, the university acknowledged the committee's report is "no longer available."

"While there is institutional memory about the work of this committee and ancillary documents pertaining to the committee's work, a comprehensive search led us to conclude that the university's copy of the report has not existed for a number of years," reads Lahey's letter.

Although the report is missing, the punishment meted out on Hankey is well known: "King's professor suspended a year after allegations," reads a May 1991 headline in the Halifax Daily News.

Hankey was suspended from the university without pay for one year and banned from ever living in residence again.

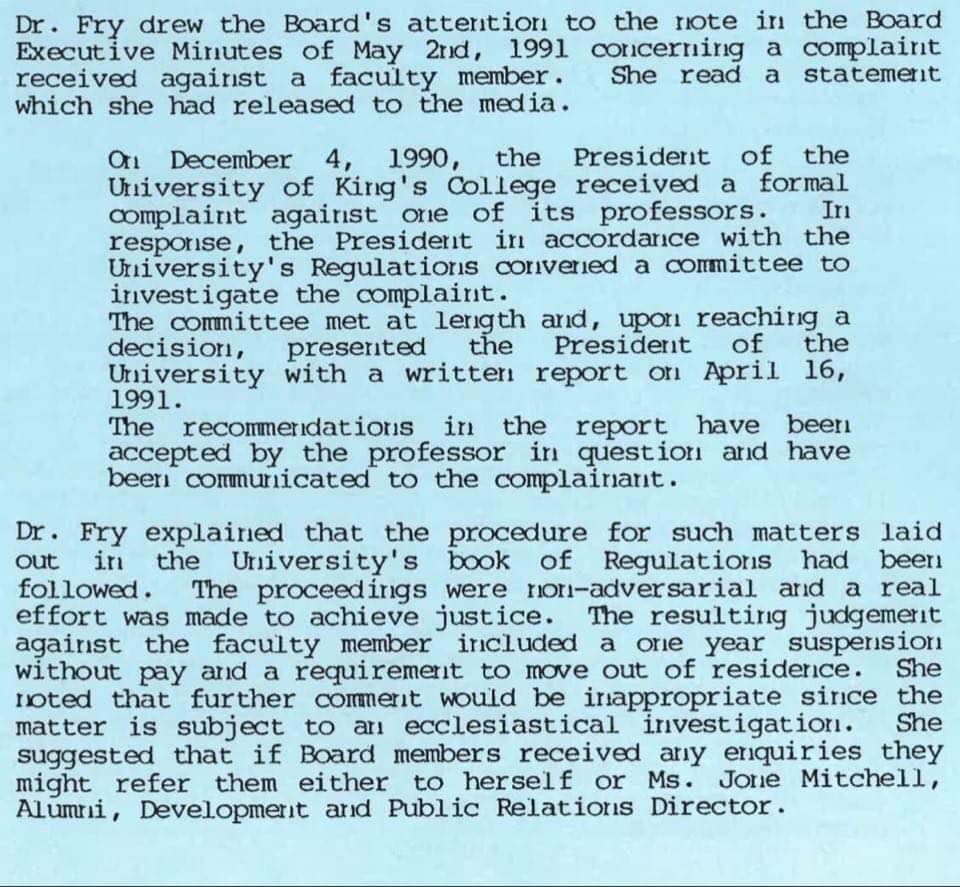

In the minutes of a King's board of governors meeting, Fry said the investigation followed the university's regulations, and claimed that "the proceedings were non-adversarial and a real effort was made to achieve justice."

However, the victim in the case, who has previously spoken publicly about it, said the university never once contacted him during its investigation.

Fry refused to speak with the CBC when she was contacted by phone in May.

One of the people responsible for the report, King's professor Dennis House, also declined to be interviewed. Another, then-vice-president Angus Johnston, died in 2017.

An expert in the field of sexual abuse and the clergy has previously told the CBC that a one-year suspension would have been a "fairly typical" institutional response to allegations of sexual assault in 1991, and that sexual abuse was seen as a "treatable condition" at the time.

Hankey was absent from King's for two years, including the yearlong suspension and a year's sabbatical.

By the time he came back as an associate professor of classics, Colin Starnes had taken over as president.

Starnes said he was not involved in the decision to discipline Hankey, but said at the time, the church's and university's responses seemed to him "the best they could do."

"It was certainly intended to be plenty because he is now Wayne Hankey with these judgments against him."

Starnes, who was president from 1993 to 2003, said he had never heard of any sexual misconduct or assault allegation involving Hankey before the 1990 allegations came to light.

He said he never heard of any afterward, either, adding that he would have been surprised if he did, because of the "searing pain" and "untold misery" for everyone touched by the consequences of the 1990 allegations.

"But he got to be very famous," Starnes said of Hankey, "and that can make it hard to see things. And he didn't get to be very infamous, and that, too, can make it hard to see things."

There had been other warnings, some dating back as much as two decades before Hankey's church trial and university suspension.

A former chaplain complained to both King's and the Anglican Church about Hankey's behaviour and quit his university post when the school failed to act.

Dan Trivett said he recalls his father, Rev. Don Trivett — who was chaplain from 1965 to about 1973 — talking about his decision to quit in later years. Don Trivett died in 2013.

"He was just frustrated. People were coming to him and saying this was happening in the dorms and wherever else, in the pool — it used to be there as well — and he couldn't stop it," said Dan Trivett.

"He decided that it wasn't an environment he wanted to be in. He couldn't condone working there."

Dan Trivett said he doesn't know exactly when his father made the complaint to the Church and King's. The two bishops of the diocese in the 1970s have both died.

The current bishop of the Diocese of Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island, Rev. Sandra Fyfe, said she could not comment on any allegations involving Hankey due to privacy considerations.

The president of King's at the time of Don Trivett's departure, and for several years before that, was Graham Morgan. Reached by phone in June, Morgan said he does not recall having such a conversation with Trivett, and said he had never heard of inappropriate sexual behaviour by Hankey at the time.

The former president had, however, had his own conflict with Hankey.

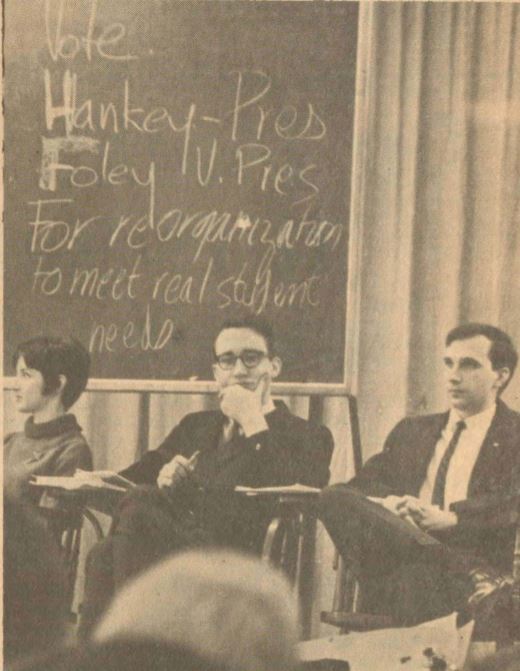

In 1976, Morgan requested Hankey's resignation from the position of director of the school's Foundation Year Program due to Hankey's behaviour toward him, including "the presentation of ultimatums and the levying of threats of withdrawal if I did not pursue a particular course of action," according to a letter from Morgan to Hankey in March of that year. Hankey was seeking control over the hiring and firing of the program's tutors, and wanted more clarity on his official job description.

Morgan told him if he did not resign, he would recommend to the board of directors that he be terminated.

Hankey appealed to a college committee, garnered support from colleagues, consulted a lawyer and wrote a 13-page, single-spaced, typewritten letter to the bishop and chair of the King's board arguing why he should remain.

Documents viewed by the CBC about the dispute do not reveal exactly how it was resolved, but Hankey continued on as director until 1978.

Turning a blind eye?

Aside from the one-year suspension, Hankey continued to teach at King's and neighbouring Dalhousie University until he retired in 2015, and he taught on contract at Dalhousie until the first charge was announced on Feb. 1.

While King's has announced its independent review, Dalhousie has remained largely silent about the allegations against its longtime professor. In a statement issued Feb. 1, Dalhousie said it was committed to providing a safe environment and encouraged anyone who has experienced sexualized violence to come forward. The university declined an interview with CBC, as the allegations are before the courts.

Hankey was a powerful figure on the King's campus.

Sitting at the helm of the Foundation Year Program at its inception, Hankey helped steer the university away from earlier financial troubles, and the success of the program resounds today as it continues to draw students from across the country.

The college's new library, which Hankey helped plan, and which opened during his absence in 1991, reflected the school's aspirations of becoming a heavy-hitting academic institution.

He was a smart administrator, a good fundraiser and, of course, a valued academic.

For students, one of the appeals of King's is its tight-knit community, not only among students but also between students and professors. It's not unusual, for instance, for professors to mingle with students in the campus pub, the Wardroom, after a lecture.

Hankey was well known for hosting soirees with selected students at his home.

Chris Parsons, who between 2004 and 2016 was affiliated with King's in various roles including as a student, a paid staff member of the student union, a teaching assistant and a member of the board of governors, said that type of social levelling was exciting for students, who could crack open a beer alongside someone who'd just lectured them about something they barely understood.

But he believes it also contributed to a culture where inappropriate interactions or relationships between students and professors were accepted.

Stephanie Potter, who took the Foundation Year Program at King's and then studied classics at Dalhousie from 2001 to 2006, said while Dalhousie had clear expectations about the boundaries between faculty and students, "it wasn't like that at King's."

"Every other university was 20 years ahead of them," Potter said.

Both Potter and Parsons wonder if that permissive culture shaped how King's responded to some allegations about Hankey over the years, perhaps viewing some as consensual encounters when they were not.

Today, the sexualized violence policy at King's — which was adopted in 2018 — says the university believes sexual or romantic relationships that involve a power imbalance have the potential to cause harm and tells instructors to "avoid such relationships."

Stories about Hankey and the pool were passed down from generation to generation of students, though the details became murky over time, like a game of broken telephone.

Some students were warned by their parents to keep an eye on him. Some frosh were warned by upper-year students.

While such stories are sometimes dismissed as rumours, current King's student Megan Krempa said a so-called "whisper network" — an informal network of voices that have been suppressed by those with power or authority — is critical to protect people who don't feel they can speak out.

"Whisper networks are the reason why I knew as a first-year student to avoid Wayne Hankey," said Krempa, who is studying philosophy and the history of science and technology and is involved with the King's chapel, which until recently was frequented by Hankey.

"Whisper networks were the only thing that could keep students safe from Wayne Hankey until such a time in which, unfortunately, charges could be laid so that the ... situation could be public and credible enough for action to be taken."

Hankey, an Oxford graduate and Aquinas scholar, was revered and feared by his students. He was celebrated by many as a supreme orator and brilliant thinker.

He frequently had a coterie of students — a clique nicknamed the "God Squad" by others — surrounding him as he walked the halls or crossed the "quad," the grassy area and parking lot at the centre of the school's campus.

He was powerful enough to make or break a student's academic career.

Hankey was also a demanding professor and a hard marker who ridiculed and belittled his students in front of their classmates.

"He was really mean," said Anne Theriault, who was a student in the classics department at Dalhousie between 2001 and 2003. "He enjoyed telling students how stupid they were…. It was kind of constant, low-grade abuse."

Hankey's "signature move," Theriault said, was to prowl around the classroom and put his leg up on a student's desk and lean right into their face, with his crotch also near face level.

Theriault said Hankey often made sexist comments, saying university wasn't designed for the "female mind," that women should have their own educational institutions and that if it was up to him, he wouldn't teach women.

Hankey was strongly opposed to the ordination of women and, when King's was debating in 1987 whether to include oral contraceptives in the student health plan, he spoke out against the idea, saying it "might encourage more sexuality."

Male students were sometimes targeted in a different way in his classroom.

Theriault said Hankey would make comments about one of her classmates in particular, saying "you're eating that banana so suggestively," or once telling him "now we're all picturing you in your swimsuit" after swimming was mentioned.

The target of those types of remarks, Jesse Blackwood, told the CBC that he never felt uncomfortable with the comments Hankey made about him.

He said although he hasn't been in regular touch with his former professor in 10 years, he considers Hankey a great teacher who has influenced him far beyond the classroom.

"Wayne taught me to think, to write, to open my mind to the world of the intellect and to grow, and in the strength of the intellect to identify what's beautiful and valuable and worth living and defending and to just take joy in those beauties. I think that that's certainly what I'm grateful to Wayne for."

'The severity of Wayne's behaviour and overall persona was always given less attention than Wayne's intellect and prowess as an academic.'

Potter, who studied medieval philosophy and theology and took every class Hankey offered, said he was academically brilliant and motivated her to do her best.

"I loved him. It's such a strange thing — a little bit like Stockholm syndrome maybe — but I loved Wayne," said Potter.

She said Hankey was thoughtful and kind, dropping off care packages of artisanal jams and cheeses on her doorstep when she had joined a religious order and taken a vow of poverty.

Other students have said Hankey was generous, offering to help them out financially or inviting them over to take care of small tasks around his home and pay them for their efforts.

But Potter was also wary of him because of his treatment of female students and because she'd been warned by several people in her first year to keep an eye on him around male students.

She and other students were uneasy about, for instance, leaving their male friends behind at his Christmas party when everyone had been drinking and Hankey was draped across a chaise longue, "like a Rubens painting."

"It had everything to do with the fact that he just acted like a predator, like every predator we had all ever met," Potter said.

"But I think by the time we got there, we had sort of thought Wayne had been chastised and chastened."

Although Hankey undoubtedly felt the sting of his 1991 suspension, it was not the last time he would be chastened by King's.

In 2019 — after his retirement — the university banned Hankey from the campus chapel after a member of the choir who is also a former student said Hankey made an unwanted sexual advance on him.

Aaron Shenkman, now 31, said Hankey had invited him to his home for dinner one evening in April, 2019.

That evening, Hankey talked to him, unsolicited, about his views on masturbation and about a family member's sex life. At one point, Hankey requested a peck on the cheek and grabbed Shenkman's leg.

Shenkman said the experience was disturbing not just because of the unwanted physical contact, but because Hankey had previously been an influence on him, helping shape Shenkman's philosophical and even ethical outlook.

Hankey was seen by some students almost as a sage, Shenkman said.

"Most people don't drink that Kool-Aid. If you do, I think it is a form of grooming," he said. "If you start to worship at the temple of Wayne, your moral compass becomes very aligned with him."

So, that evening in Hankey's apartment, with the lamb and oysters and wine, shook him. The things he valued — things he had learned from Hankey — were now tainted.

When Shenkman told the chaplain and choir staff that he was quitting the choir because he didn't feel comfortable around Hankey, it affected his friendships and created divisions within the chapel community.

Shenkman said some were seemingly unable to understand why he was upset. One expressed surprise that he was "so fragile."

Some said that regardless of the harm Hankey was causing to the community, it would be more harmful to ask him not to go to church.

"Others reflected that Wayne, just an old man, simply wanted to appreciate the music in the chapel," Shenkman said. "Neither of these positions made me feel supported or cared for, and replaced the need to care for community members with the need to acquiesce to the desires of one man."

That acquiescence was a longtime problem at King's, Shenkman said.

"The severity of Wayne's behaviour and overall persona was always given less attention than Wayne's intellect and prowess as an academic," Shenkman said.

"Somehow stories of him driving students to tears in his classes, bullying visiting speakers, and generally being transgressive and inappropriate were collected more as delightful curios than compelling indictments…. That institutional acceptance made it extremely difficult to accept his behaviour as anything other than an interesting and vibrant part of collegiate life."

Krempa, the current King's student, said after she learned of the situation involving Shenkman — but before the criminal charges were laid this year — she wanted to write an article for the student newspaper about Hankey in an effort to force the university to finally reckon with him and his legacy.

She said she was cautioned by a trusted and supportive professor that, "Wayne Hankey will destroy you."

That reputation is part of what kept Hankey in power and on the payroll at both King's and Dalhousie for so long, Krempa said.

"He just glided through on the knowledge that nobody was really willing to risk their career, risk their livelihood, risk their personal relationships with other people to hold him accountable."