July 10, 2019

As a longtime journalist, you inevitably gather notebooks, memories and boxes full of stories.

If you’re lucky, you get to revisit some of those stories.

In 1988, Canada was part of an international effort to end the apartheid regime in South Africa.

It was an extraordinary coordination of world trade and travel sanctions which squeezed South Africa to the brink, toward the so-called “rainbow nation” in 1993 that ended institutionalized segregation. At the time, it was one of the biggest stories in the world.

It was then, as a young journalist, I, perhaps naively, jumped at the invitation of a colleague, a bureau chief for an international satellite news organization in Johannesburg, to see that part of the world first hand.

I witnessed the segregation, felt the tension, the indignation, the fear.

Now, more than 30 years later, I had the opportunity to return to South Africa to be part of an event unimaginable in 1988, not to mention demonstrably illegal and, considered by some, immoral.

An interracial, same-sex marriage

In full view of hundreds of tourists, my nephew Ramsey married his partner Abel on top of Table Mountain on the southernmost tip of the African continent. Due to concerns for their well-being, CBC News is only using their first names.

Their union gave me an opportunity to reflect on the past, and look at how far that country has progressed.

And, of course, take stock of my own personal journey.

Try as I might, I could not find the photos of my 1988 trip. They’ve been lost to decades of moving and life.

This, remember, was well before iPhones and the internet. I recall being apprehensive about even bringing a camera along.

As a young woman travelling alone, I didn’t want to attract attention.

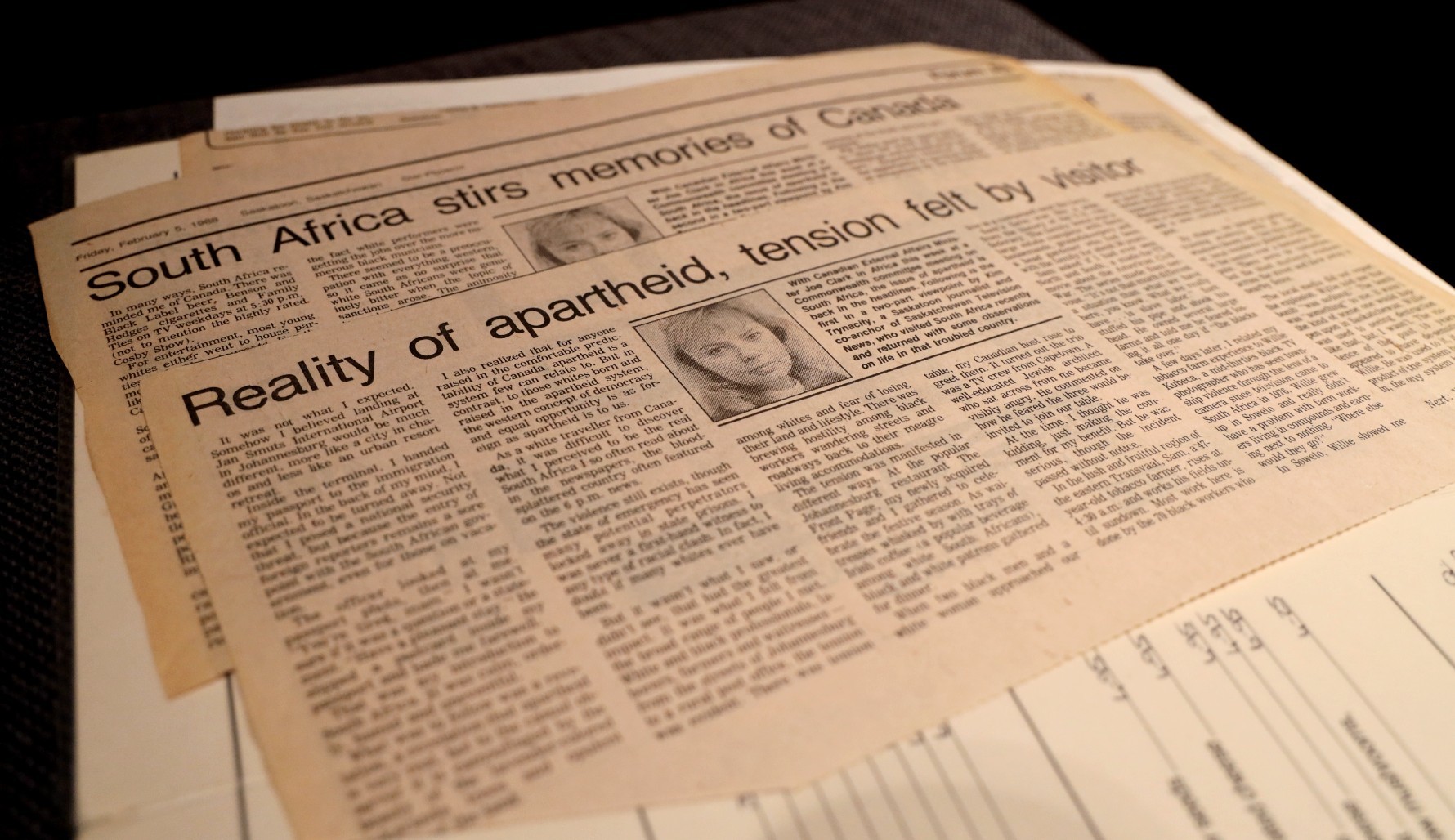

I did however discover a menu from the Johannesburg Hard Rock Cafe and inside two articles I wrote for the Saskatoon Star-Phoenix newspaper.

I went to South Africa at the height of the worst violence of apartheid.

The stories I wrote described the people I met, the tensions I observed, and the stark contrast with my comfortable Canadian life.

Re-reading them now took me back to my visits in 1988 to Johannesburg, Cape Town and the township of Soweto.

I went to Soweto with black cameraman Willie Kubeca.

I recall him telling me to keep my head down when I was in the back of the car as we drove past Winnie Mandela’s compound surrounded by barbed wire and young security guards.

He showed me a building where a bomb exploded the day before, blowing out all the windows.

He told me it was “nothing.”

This was a crew that captured the brutal human tire burnings and violent uprisings.

And then, there was Cape Town.

An outpost of progress and inclusion even back then. And its natural splendour.

Cape Town is extraordinarily beautiful.

I remember driving up to Table Mountain, the defining landmark of the region, in a VW Kombi van with a small group of visitors.

The tour operator told us about the beauty of the mountain, the surrounding wineries, and asked us where we were from.

I was the only Canadian.

The tour guide switched from wineries and wildlife to politics.

She sneered at the “unfair treatment” by the “West” and how South African athletes were no longer welcomed to compete with the world.

Yachtsmen from prestigious Cape Town clubs were left to sail solely against one other. Only golfers from Brazil, she told us, would play with South Africans.

That story stuck in my mind all these years. Economic assumptions aside, it was the snubbing of athletes by the international community that made an impact on the tour operator.

South African marriage officer Dion Goldie performed Ramsey and Abel’s wedding ceremony.

Goldie grew up in South Africa during the apartheid era. He was conscripted into the army and lived overseas for a while before returning to Cape Town.

Marrying a same-sex interracial couple during apartheid would have been out of the question, much less doing so on Table Mountain, Goldie said.

“You would never,” he said when I spoke to him from his home in Cape Town recently. “Same-sex weddings were illegal. Interracial weddings were illegal. It would have been the holy grail of the most unlawful of weddings, so to speak.”

While times have changed, he still doesn’t see many interracial marriages.

When he does it’s usually white European men marrying women of colour from South Africa, he said.

Same-sex unions however, are becoming more common, now making up about 10 per cent of his business.

“I mean there are still communities today that don’t accept same-sex weddings or interracial,” he told me.

“You’re always going to get people who are against it, who fight against it, whatever their personal beliefs are.”

Ramsey and Abel wanted to marry in South Africa because it’s where Abel grew up. Besides, it’s a great place to escape the winters of London, where they live.

Abel is also from a generation that never experienced apartheid.

Apartheid officially ended 25 years ago in 1993, under the leadership of anti-apartheid activist Nelson Mandela.

He famously coined the phrase “rainbow nation,” imagining a progressive nation without a colour filter.

Since his death however, South Africa has struggled to thrive amid corruption scandals, lingering economic problems and racial disparity.

The shantytowns I saw in 1988 are still around, though new housing developments are being built nearby in an effort to give residents better living conditions.

As a money-making venture today, communities conduct tours through some of the shantytowns selling souvenirs and locally-made crafts.

I took a walking tour through historic Cape Town the day after Ramsey and Abel’s wedding.

Visitors are taken past iconic government buildings, through a park and to small monuments to what life was like during apartheid.

As a journalist in Saskatoon in 1988, I had interviewed South Africa’s ambassador to Canada, Glen Babb.

At the time, Babb was widely criticized for arguing Canada too was guilty of apartheid in the way it treated its Indigenous peoples.

After leaving the foreign service in 1995, Babb started a language translation company in Cape Town.

Babb felt enormous pride when it seemed his country would emerge from apatheid as the “rainbow nation, when everything seemed to be bright and happy.”

When I spoke to him recently, he pointed out sadly the promise hadn’t turned out the way many had hoped.

“Racial tensions have once again revived, which is a great pity,” Babb said.

He talked about the slowdown in the economy, the lack of foreign investment and the impact of poor communities becoming worse off.

But, he said without hesitation, there’s no turning back in one area.

“Ten years ago it was still strange to see a mixed couple. But now it’s just common,” Babb said.

“Nobody even raises an eyebrow if there’s interracial marriage, interracial sex, interracial communities. Things have changed enormously over the last 20 years.”

That is something I too noticed.

Under a stark blue sky, in the warm January sunshine, two men avowed their love for one other.

I was prepared for my assignment of holding the wedding rings, but not for the rush of emotion I experienced when the ceremony began.

“Well the big day has arrived,” Goldie declared.

“You guys can hold hands, by the way,” he added assuringly.

Ramsey and Abel laughed nervously, then took each other’s hand.

“Think about the progress of your relationship. The friendship that grew and from that friendship the love that has blossomed and evolved and grown deeply.”

I was overcome thinking of how tough it must have been for the couple to get to this place in life and of the huge challenges still ahead.

While streams of tourists walked by to glimpse the wedding, nobody blinked an eye, except for me as I tried to wipe away the tears.

The wedding was closing the circle on a journey I started 30 years ago.

*Due to safety concerns, some details in this story have been removed since it was originally published.