May 2, 2021

For Jaclyn Hall, being out on the land provides a deeper connection to her language and culture.

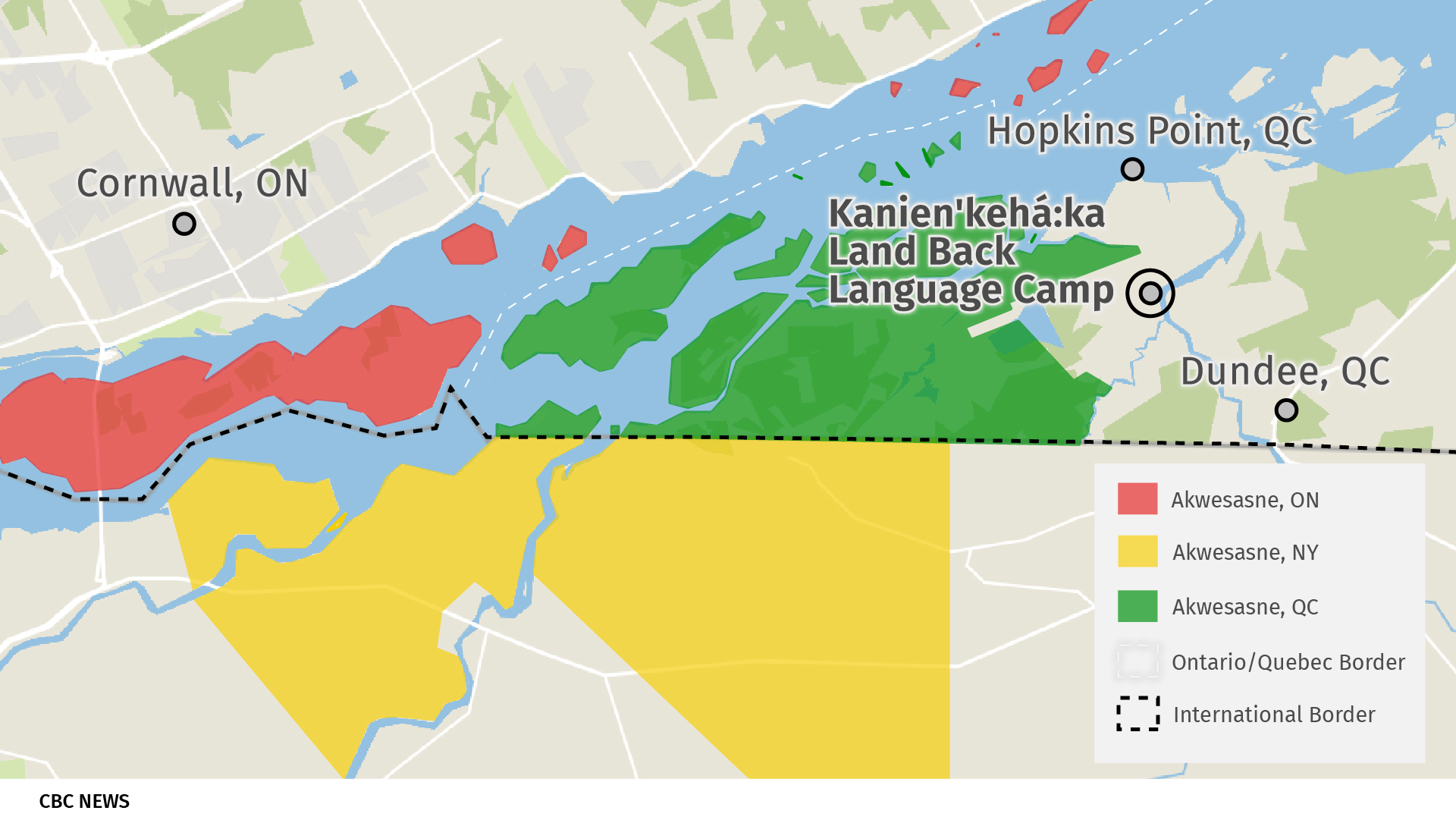

It’s why the mother of five from Akwesasne, a Kanien’kehá:ka (Mohawk) community on the Ontario, Quebec and New York State borders, has spent the last eight months building a camp to foster using Kanien’kéha (Mohawk language) and culture-based learning.

In the process, she’s reclaimed land in the Quebec township of Dundee that once was a part of the community’s vast territory — albeit to the dismay of nearby cottagers.

“I hope they could just leave us be and just let us just be on the land,” said Hall.

“It's a safe place for our family. We're just trying to take care of our kids and teach them.”

The camp site along the Salmon River has a camper for Hall’s family, a large canvas tent for visitors, a sugar shack, and a small school house is under construction. Over the last few months, they’ve fished, canoed, snowshoed, and trapped beavers and muskrats.

They’ve begun tilling the land for a garden this summer and are ready for another season of fishing.

With each activity, Hall said she strives to use as much Kanien’kéha with her children as possible.

“You're actually doing the things and using the language . . . when you're conducting yourself and not sitting there looking at a book and learning words you would never use,” said Hall.

The place where they drag the iron chains

Historically, Akwesasne called the Dundee area Tsi:karístisere, which means "the place where they drag the iron chains” in Kanien'kéha, referring to the survey chains used to determine the U.S./Canada border in the early 1800s.

Last year, Canada finalized a $240 million settlement with the Mohawk Council of Akwesasne over a 8,000-hectare land grievance in Dundee. The agreement includes the ability to purchase up to 7,400 hectares of land from willing sellers in Quebec and Ontario.

Hall was one of the many community members who did not agree with the settlement, nor did she participate in the referendum held in 2018 to ratify the agreement.

READ MORE: Akwesasne moves ahead in $239M Dundee land claim settlement after appeals dismissed

READ MORE: Akwesasne Mohawk council puts settlement of 130-year-old land grievance to a vote

She channeled her resistance to the settlement into starting the camp in September 2020. Her goal was to raise awareness about the amount of privately-owned land in Dundee township that has the potential to be returned to Akwesasne.

The camp is located in an isolated area west of the Salmon River, a few kilometres south of cottages at Hopkins Point. The area is mostly marshland and accessible only by a road from Fort Covington, N.Y., that closes in winter. It’s on one of few spots that didn’t flood last spring, according to Hall. Most of the land where the camp is was purchased by a Mohawk Council of Akwesasne corporation called Akweks:kowa when the community began negotiations over the land grievance. It has yet to go through the additions to reserves process.

Hall’s camper sits on property privately owned by two individuals. Dundee’s municipal council considers the camp an “illegal occupation” according to Nov. 3, 2020 meeting minutes.

Hall expressed a willingness to buy the land but neither of the parties have reached out to each other.

“People in Dundee believe they own this land when we never surrendered it,” said Hall.

"I'd give them the market value for that property or nothing. You know they didn't really give us that choice but I'm trying to be fair. They haven't been using that property. The trees were overgrowing, so they haven't been there in years. Like they weren't even utilizing the property and we want it."

Looking for a peaceful solution

The township of Dundee’s municipal council has filed complaints with the RCMP, the Sûreté du Québec (Quebec’s provincial police force), and sought assistance from the province’s Indigenous affairs minister regarding the camp, according to minutes from a Nov. 3, 2020 meeting.

Mayor Linda Gagnon told CBC News that there’s also been concerns about Hall not checking in at the border, building structures without proper permits, and occupying land that is privately owned.

“The truth is that we are in Dundee, Que., Canada. We're not on the reserve, so they have to follow the rules that we have,” said Gagnon.

“I can understand that everybody in pandemic times wants to go back in nature, and I can understand what she's [Hall] saying, but the problem is that she's on other people's properties.”

Gagnon said she’s open to speaking with the two families, and is looking for a peaceful solution.

Abram Benedict, grand chief of the Mohawk Council of Akwesasne, echoed similar sentiments.

“From a community perspective, we want to be able to exert our rights over territories that are ours but also at the same time, we want to be able to build relationships with the communities around us,” said Benedict.

“We're concerned about those two other properties that they're on that don't belong to anybody in our community. That's what's really causing some hardship for the residents of Dundee. If they were strictly on our land, it's something we can manage, but it's if they're not and it's not the reserve.”

CBC News was unable to reach the private property owners.

Feeling ‘kind of unwelcome’

Hall’s family aren’t the only ones using the camp. Chrissy Jacobs wants people to get accustomed to seeing Akwesasne community members use that part of the territory.

“I think the important piece is the action of showing my children that they are not bound by the drawn out boundaries of a reservation,” said Jacobs.

“It is their inherent responsibility to protect that undeveloped area and to have such a connection with it that they will fiercely protect it.”

Jacobs and her family have pitched a tent at the camp, picked medicines, gone duck hunting and snowshoeing as a way to reconnect with the land and grieve after the loss of a family member.

Jacobs plans on spending the majority of the summer there but is concerned about not feeling welcomed by the nearby cottagers. The police were called on her last year after one of her children laid tobacco down near the cottages.

“It’s just not a nice feeling to feel kind of unwelcome in your own territory. The kids go outside to play and everybody's watching what they're doing,” she said.

Hall said she’s open to dialogue but said decision-making does not lie solely on her. Throughout the process, she’s received guidance from traditional leaders. For her, it’s about finding peaceful solutions to have the land returned to Akwesasne.