February 20, 2021

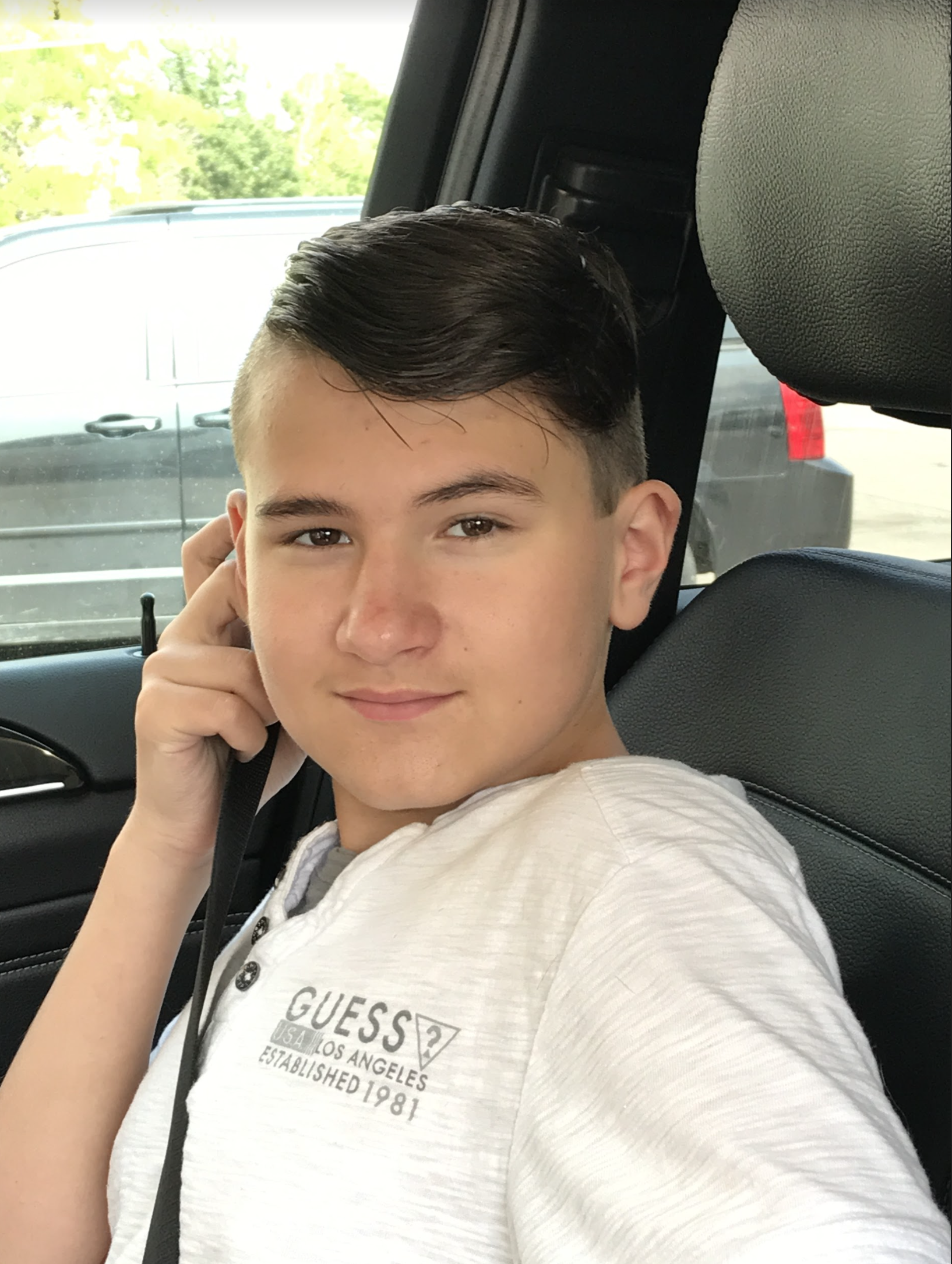

His head battered, his body bleeding and his thin,15-year-old frame only covered by a white T-shirt, David Roman struggled up the curved stairs of his foster home.

Outside, on that early February morning two years ago in Barrie, Ont., the air was frigid and still, the sun so far below the horizon that only an overcast sky obscured the stars.

Daybreak was more than an hour away but David would not see the sun rise again.

Reaching the top of the stairs, he turned left, staggered several steps and knocked on the bedroom door of 24-year-old foster parent Jordan Calver.

Across the hallway in another bedroom, 15-year-old Evan opened his eyes, his hand on the phone he had held when he had dozed off. It was 5:34 a.m.

Unsure what had awakened him and his bedroom door closed, Evan could hear David and Calver. They talked about going to the hospital.

"They were stressed. Confused," Evan later told CBC.

Not wanting to be left alone in the home with another foster teen who had been violent and boastful of his supposed criminal history, Evan arose, walked to his door and opened it.

David was sitting on a hallway chair, bleeding everywhere and saying one thing over and over.

“Please help me.”

WATCH | Confused teen awakens to the sight of blood:

David would not survive the coming attack, but his parents won't let his final plea die, too, filing a lawsuit they hope will spur change to a foster system where they say profits trump the care of kids.

In Ontario, children's aid societies place an estimated one in five foster kids in homes operated by the private sector, most of those for-profit companies. But while the responsibility is immense, an investigation by The Fifth Estate has found the level of public oversight is minimal.

Among the investigation's findings:

- The Ontario Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services allows any adult who hasn't been convicted of certain crimes of violence or abuse to be a foster parent even if they have no relevant education or experience.

- Private companies operating foster homes claim expertise on licence applications by checking boxes that are not scrutinized by the ministry and then use licences to market themselves as having expertise.

- Collaboration among children’s aid societies is encouraged but not mandated.

As of 2016, companies were licensed to look after as many as 2,291 foster youth in Ontario, the most recently posted government figures show. That number is about the same as the combined total looked after by foster parents trained by children’s aid societies in Toronto, Ottawa, London-Middlesex, Windsor-Essex and the Toronto area regions of Durham and Peel.

There are more than 60 licensed companies and when they run their operations to capacity, they are eligible to be paid between $125 million and $167 million a year, according to CBC estimates. That money comes from Ontario taxpayers, with the government routing funds to children’s aid societies, which then typically pay between $150 and $200 per child per day.

Those companies also get money from children’s aid societies to operate staff-run group homes that provide about 1,504 spots, with higher daily pay rates pushing their total potential annual revenue above $200 million.

"The buck stops with the government," said Irwin Elman, Ontario’s first and only child advocate, whose office was shut down in 2019 by the provincial government after it issued a damning report on the state of foster care. "The government didn't want to accept responsibility, because if it accepted responsibility, it would have to do something."

I.

A dozen years before David Roman was born, his parents, Elena Dvoskina and Antonio Roman, fled Russia in 1991. They came to Canada, leaving their only child, a seven-year-old daughter, behind with family. She followed in 1995.

For years after, the couple did not consider having another child, but as their daughter approached adulthood, Dvoskina had a change of heart. While pregnant, inspired by a Russian book that suggested meanings for names, she chose David, which the book said meant the "chosen one."

David was born in 2003, and while Dvoskina and Roman would divorce two years later, they were devoted to their son and determined to let him explore the world with few limits.

By the time he was four, his parents were driving him two or three days a week from their home in Richmond Hill to the Ontario Science Centre a half hour away in Toronto, a routine that continued until he was eight.

"He was an explorer … a wanderer," Dvoskina said.

At school, David loved to socialize but not to conform to the routines or expectations of teachers, with whom he got in trouble. By age 10, he was diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder — ADHD. While he lacked focus, he was bright, excelling as a writer.

Dvoskina resisted getting medication for her son. In Russia, any sort of mental illness or difficulty was taboo. But by the time he was 13, she agreed to medicate her son for ADHD. His focus improved, but his interest in school did not. David tried living for a few months with his father and stepmother, but decided he wanted to stay with his mother.

At Jean Vanier Catholic High School in Richmond Hill, a suburb of Toronto, David started to smoke marijuana, straining the relationship he had with his mother.

"I never judged him, except for that weed," she said.

David started skipping classes and hanging out with new friends his mother didn’t trust, Dvoskina told The Fifth Estate. She sought help from school officials, and they tried, even telling David he could skip class so long as he stayed in the school building.

But his truancy became the norm and the school contacted York Region Children’s Aid Society. The agency called Dvoskina, but by Grade 10, he was leaving school as soon as she dropped him off.

Then, just before Dvoskina was to embark on a week-long business trip to Calgary, she found out she had cancer, scheduled surgery for the day after she returned and arranged for David to move to live with his father and his new wife. Within days, when Antonio Roman saw his son using marijuana and not attending school, he arranged for a conference call with Dvoskina and the CAS. Both asked for a foster placement while retaining custody.

The placement at a Newmarket foster home lasted a couple of weeks, but when David still refused to attend school, and with Dvoskina back home after a stay in hospital, her son returned. Increasingly frightened that her son’s truancy would force the school to expel him, Dvoskina again sought help from the York Children’s Aid Society.

"I didn't know how to act, how to reason with him. In my mind it was my last hope," she told CBC.

A children's aid society social worker suggested a new foster home in Barrie that he said specialized in kids who were truants — a claim that baffles those in the field who say there’s no such specialization and that only 44 per cent of foster youth graduate from high school, compared to 81 per cent for all Ontario students.

The new home, an hour away, would also separate David and the friends with whom he used marijuana.

"He will be with knowledgeable people who know how to make sure that kids are learning, going to school," Dvoskina said.

She gave her son an ultimatum: return to school near home or go to Barrie.

He chose the latter.

In December 2018, David’s parents drove him to Barrie to see the home and meet Calver.

Roman didn’t like what he saw: a young adult with no background in social work who was not much older than his son. Dvoskina saw that, too – but something else. David and Calver seemed to bond.

"He didn't impress me as a father figure," Dvoskina told CBC. "But then I thought that maybe Jordan [would] understand David more than I could."

From Dec. 17 to 20, David was the only foster child in the home, and when Dvoskina would phone, she’d hear in her son something that had been absent for years: laughter.

II.

The Barrie foster home where David Roman was staying was operated in February 2019 by a for-profit company called Expanding Horizons Family Services.

The house on Penvill Trail looks impressive with its nine-foot ceilings, four bedrooms and three bathrooms. The same may be said about the website Expanding Horizons created to promote a business incorporated in 2010.

As late as September 2020, the website listed what seemed like an impressive roster of staff, but those claims unravelled when scrutinized by The Fifth Estate and it was taken down after CBC sought interviews with those who run the company.

The consulting psychiatrist, Dr. Frank Smith, was chief of psychiatry at a hospital in York, Ont., decades ago, but his wife told The Fifth Estate he retired in about 2013, hasn’t been licensed since 2016 and at age 83 is being cared for in a long-term care home.

The person identified on the Expanding Horizons website as its executive director, Marilyn Malton, said she never played that role and had asked the company to remove her name. Malton is a retired school principal who tutors kids and said that years earlier, she helped the company get started as an educational consultant.

The company’s legal counsel, Derrick McNamara, helped the company to incorporate, but surrendered his law licence in 2018 after misappropriating nearly $500,000 from clients.

Karen Lo Greco, wife of the program manager Frank Lo Greco, was listed as a "registered behaviour consultant," but such a designation doesn’t exist in Ontario.

Asked by The Fifth Estate whether ministry officials review websites of foster companies before issuing licences and renewals, a spokesperson said they did not unless someone flagged a concern.

Since Expanding Horizons created its website, at least 16 children’s aid societies have placed foster children in the company’s care.

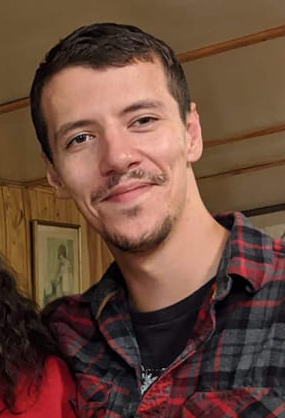

Jordan Calver was 23 and pursuing a career as a chef when he heard Expanding Horizons wanted to hire a foster parent, so he reached out and was invited to meet Frank and Karen Lo Greco in September 2018 at a Starbucks in Barrie. The couple told him they'd place only youth who were not violent or disturbed under his care and would support him so he could meet their needs, according to an $11-million lawsuit Calver filed against the company, the Hamilton children’s aid society and staff at each, including the Lo Grecos, and the youth charged in David’s killing.

Calver’s training was done on Nov. 26 and 27 at a public library. When that training included how to physically restrain youth, Calver expressed alarm, but Lo Greco assured him the company would place no violent youth with him, the lawsuit alleges. The only other training was to observe another foster parent for a few hours, and a CPR course the following February.

Calver visited the Penvill Trail home Oct. 31 and was asked on Nov. 3 to sign a $2,200-a-month lease. Later that month, he signed an agreement in which Expanding Horizons promised to train and support him, and react promptly should Calver request help, the lawsuit alleges. Calver moved into the foster home in December, days after his 24th birthday.

On Dec. 17, David Roman arrived. His parents didn’t know Expanding Horizons was already considering a placement there for a 14-year old in Hamilton whose troubled, violent and criminal history had been misrepresented to Calver by Lo Greco and the Hamilton CAS, the lawsuit alleges.

Four days later, a social worker drove from Hamilton to Barrie to drop off the youth who would be charged two months later with first-degree murder in David’s death.

Ten days after the Hamilton youth arrived — CBC is using the pseudonym James because a youth charged can’t be named — he tried to rob a nearby Hasty Market, telling a clerk he had a gun. When no gun was found, James was charged with trespass. Calver alleges that was the first of many serious occurrences he emailed to Expanding Horizons.

According to the lawsuit, those occurrences include:

- On Jan. 5, 2019, Calver found James under the influence of drugs and with white powder Calver suspected was an illegal drug but Frank Lo Greco told him not to notify police.

- James threatened to kill Calver twice, first on Jan. 9, saying he’d put him “to sleep” and that he “wouldn’t get a chance to call for help.” The youth bragged about committing crimes before he was placed in the Barrie home. Lo Greco discouraged him from filing a serious occurrence report to the ministry.

- On Jan. 30, James broke down Calver’s locked bedroom door. Lo Greco promised his wife would provide one-on-one support, but that never happened. Instead, the following day, the company added a third foster teen, and on Feb. 5 a fourth teen, sent there from youth detention after being kicked out by a seasoned foster parent in another Expanding Horizons home who had a live-in social worker, the fourth teen told CBC.

"It's breathtaking in its outrageousness," Elman told The Fifth Estate of placing four teens, two with a history a violence, with a young, rookie foster parent.

There’s "more than one victim in this situation. Certainly that child who died is one and my heart goes out to his family and loved ones and to the world that's now not going to see him reach his full potential," Elman said. "But those other [foster youth], they're victims, too. And that [foster parent] is a kid. He's a victim, too. It was a set-up from the beginning.

WATCH | Foster system driven by money, expert says:

The lawsuit alleges that when Calver asked Lo Greco for help managing James’s medicine and fetal alcohol spectrum disorder, Lo Greco told him to Google it. When Calver asked for support, the lawsuit alleges, Lo Greco told him to find his own staff. Ontario allows up to four foster youth per home but placements of one or two are typical, those in the field say.

James became more violent in mid-February, alleges the lawsuit and the third and fourth teens placed in the home, who spoke to The Fifth Estate. Since both are potential witnesses in the criminal case involving James, CBC is using the pseudonyms Evan and Nick.

"Most of it was him coming into my room, unallowed, and so I'd tell him to leave, and he'd start grabbing me and trying to hit me," Evan told CBC. "He bragged about [being in youth detention]. He'd say how he’s gang-affiliated…. I didn’t believe it [but] I just kept my distance."

James had a teardrop tattoo below his eye that some get as a badge of being incarcerated and wore laceless shoes of the sort given to youth in detention, Nick said.

On Feb. 15, James threatened Calver and staff at a school where the foster parent tried to enrol him, and later that day, threatened to kill Calver because his skateboard had gone missing, the suit claims. The next day, after Calver found James and Nick using cannabis in the house, James shoved the foster parent, Nick said.

On Feb. 17, James kicked down Calver’s locked bedroom door while the foster parent was out shopping. Barrie police arrested James. Calver told Expanding Horizons and a social worker with the Hamilton children's aid society that James could not return for safety's sake, the lawsuit alleges.

Both pressured Calver to take James back, the suit alleges, the society because it had no other available placements and the company because rejecting the youth would strain the relationship between it and the agency. Lo Greco wanted Calver to provide seven to 30 days notice before removing James.

Calver also told Evan and Nick he was trying to keep James out of the home, the two teens told CBC.

Only after being pressured by the company and CAS did Calver allow police to return James Feb. 18, the lawsuit alleges. The following morning before 6 a.m., Calver was awakened by the sound of David knocking on his bedroom door.

III.

Companies clear two hurdles to look after foster kids in Ontario. First they get a licence from the ministry and convince children's aid societies they can provide needed, quality services. Once a company obtains a licence and before it can care for children, it must sign agreements with children’s aid societies, whose scrutiny begins when a company seeks a placement of a foster child.

Companies are required to submit reports that detail the services offered and how foster parents are selected, trained and supported. The societies also speak to those who run the foster companies and can interview foster parents. But while reports are read and discussions had, agencies trust companies to describe honestly what they do.

And when one society places a foster kid in the jurisdiction of another, co-ordination and communication vary. The umbrella association for children’s aid societies urges them to share what each knows about foster youth, homes and private agencies. While many do, there is no mandate.

When children's aid societies select foster parents, they follow a process that can take 12 months, assessing candidates and their homes using a method known best by its acronym, SAFE, then training foster parents using a program called PRIDE.

But Ontario restricts PRIDE to public agencies. For-profit companies cannot use it. SAFE is available to companies but not required. That leaves foster companies to decide how to select and support foster parents.

IV.

Expanding Horizons president Carmine Perrelli, who serves as its senior finance manager, is also deputy mayor of Richmond Hill and longtime ally of the Ford family — a political dynasty in Ontario, where Doug Ford is premier and his late brother Rob was mayor of Toronto.

Elected in 2010 as a councillor in Richmond Hill, Perrelli grabbed the spotlight in 2013 when he defended Rob Ford after a rival candidate for mayor of Toronto accused Ford of groping her at a party. Perrelli told the media the accuser planned to entrap Ford.

In 2014, Perrelli lost his seat on council and a $100,000-plus annual pay cheque when he failed in his bid to become mayor of Richmond Hill. In 2018, he was elected as a regional councillor who also represents his city on York Region council.

Seven months after David Roman was killed, Perrelli held a festival with campaign-like signs and attendees who included the Lo Grecos. Perrelli refused to tell the media who paid for the festival but was eager to pose with his guest of honour, Ontario Premier Doug Ford.

As a private company, Expanding Horizons isn’t required to disclose its revenue. Soon after David's death, the ministry restricted the company to 21 foster care beds. Its per diem payments were in the typical range of $150 to $200 per day, per child, and if those beds were occupied year-round, that could generate annual revenue of between $1,368,750 and $1,825,000.

Using those same estimates and assuming full occupancy of its four beds, the Penvill Trail foster home would have generated revenue of between $219,000 and $292,000. According to a cash flow statement the company provided to the property owner, later obtained by The Fifth Estate, Expanding Horizons projected annual expenses there would total $69,840.

Phoned by The Fifth Estate, Perrelli said he was struggling to hear, but as host Bob McKeown described what CBC had learned, Perrelli asked for questions in writing.

When emailed questions failed to generate a response, McKeown phoned a week later, and Perrelli said he was struggling to hear and hung up. The Fifth Estate went to Perrelli’s house but a resident there said he was not home.

CBC sought an interview with Frank Lo Greco but he declined.

WATCH | The politician behind Expanding Horizons:

On Feb. 19, 2019, with David bleeding and dazed, Calver phoned 911 and grabbed a towel to clean off the blood, his lawsuit alleges. Evan says he retreated to his bedroom, leaving his door ajar, and said he saw David stabbed by a youth wielding two knives.

Dressed only in boxers, Evan hid under the sheets of his bed, feigning sleep, then hid in the closet before bracing his body against his closed bedroom door. He then fled through a window onto the small roof above the front door landing, he told The Fifth Estate.

Evan recalls a blur of blades and blood, the brutish details of an attack later recorded in a post-mortem report. David was stabbed 20 times, including six times in the head, twice in the chest, once each in the stomach and back and eight times in the neck. He bled to death before paramedics arrived. After the last blow, he was alive for at least seconds, and perhaps as long as a few minutes, forensic pathologists estimated.

An autopsy later would find traces of medication in David, including antipsychotics that he was never prescribed. That finding matches observations by Evan, who said he saw David the night before he was killed take meds that were not his.

Evan saw James flee the house, and afraid he might return, Evan climbed back into his bedroom, raced down the stairs and locked the front door, he told CBC.

When police and paramedics arrived, officers broke down the front door and that noise woke Nick.

"I opened the door and saw David.… He didn't look like he was, um … sorry, this is really hard," Nick said. "There’s a lot of blood everywhere and he didn’t look alive. There were a lot of stab wounds and the worst part was that the handle from the knife broke off and the blade was actually stuck in his throat."

V.

At the time David Roman was killed, ministry officials had been slow responding to a damning report about Thunder Bay group homes run by another for-profit company, Johnson Children’s Services, said Elman, whose office, the Ontario’s Advocate for Children and Youth, penned the report.

Johnson Children’s Services entrusted youth who were depressed, attempting suicide and battling substance abuse to staff who were mostly new to the field, had received little training, and who were unable to de-escalate volatile situations, according to the child advocate’s report. The lack of oversight ended only after a whistleblower called the Child Advocate’s Office, which contacted the ministry.

In David’s case, oversight intensified after he was killed. Six hours after the fatal stabbing, the ministry’s Central Region office sent an email to 12 people in the ministry. The recipients, for the most part, were experts in managing a media crisis.

"There has been media attention, however no connection to child welfare services mentioned," Sarah Ballantyne wrote in an email, some of the hundreds of pages of records The Fifth Estate obtained.

David's death triggered investigations by the ministry and children's aid societies, but when CBC requested those reports, the ministry shared them after redacting them in their entirety.

While the ministry won't say what it found, after David’s death it ordered Expanding Horizons not to open new homes or accept new children in care, reduced the number of youth it could care for to 18 and imposed dozens of conditions on its licence, including:

- Before accepting children into care, Expanding Horizons must create safety plans to prevent behaviours that would place the child at risk, train foster parents to safely de-escalate conflict and report serious occurrences to the ministry. It also must disclose to placing agencies the length of time foster parents had been approved to provide care, the number of foster youth already there and the schedule of support staff.

- After a child was admitted into care, Expanding Horizons must review weekly with foster parents serious incidents, whether they have concerns about managing youth. When they do, they must document the company’s response and report concerns to the placing agency or person.

More should be done to vet foster parents, Jill Dunlop, the associate minister of children and women's issues, told CBC.

"We were looking at furthering that system so that there's educational qualifications as well," she said. "We are working on legislation to come into place in the next two to three years … we know that we can do better and we must do better for children who are in care."

The ministry inspects only 10 per cent of foster homes each year but that will change, she said.

"We are committed to increasing the number from 10 to 20, and to eventually 50 in the next two to three years."

WATCH | We can do better, associate minister says:

The three children’s aid societies that placed youth in the Barrie home declined to be interviewed but issued a joint statement that expressed regret and called for changes.

"We know that serious systemic issues — ranging from the quality of care provided in residential services, the need for more robust staff training and the need for an improved system of licensing and oversight — must be addressed by residential service providers, government and child welfare together in partnership," wrote York Region Children's Aid Society, which placed David in the home, the Children's Aid Society of Hamilton, which placed the youth charged with murder in his death and Simcoe Muskoka Family Connexions, which placed two youth who witnessed David’s death.

At least until now, the need for reform has stalled because the Ministry and CASs have dodged responsibility and blamed each other, Elman told CBC. “That dance has been going on forever, and the buck never stops anywhere and children are caught in the middle.”

The lack of oversight over for-profit foster companies is inexcusable, said the lawyer representing Elena Dvoskina and Antonio Roman, Alex Van Kralingen. "They're warehousing children. There’s something manifestly wrong about that."

On May 29, 2019, the ministry ordered Expanding Horizons to create a written protocol by June 7 about how the company would respond when a foster parent is unwilling or unable to provide care for a foster youth.

That protocol, later obtained by CBC, was not issued by Karen Lo Greco until Sept. 11, 2019, more than three months after the deadline.

While an investigative report by Simcoe Muskoka Family Connexions was redacted by the ministry, a letter dated July 18, 2019, from that children's aid society to Perrelli appears to blame David's death on Calver rather than the company.

"Our involvement in this matter is complete and this file will now be closed. Should the society learn that the foster parent resumes care of children through your employ, the society may be required to assess the situation further," Simcoe Muskoka Family Connexions wrote.

On Oct. 7, less than eight months after David was killed, the ministry renewed the licence of Expanding Horizons, a copy of which was obtained by The Fifth Estate.

I don’t understand why this company continues to be licenced to house children.

Asked how that was possible, Dunlop said: "It's important that we [understand] it's the director of inspections who makes those decisions on a licence."

That decision makes no sense, Van Kralingen said. "I don’t understand why this company continues to be licenced to house children."

The veil of secrecy imposed by the ministry leaves critical questions unanswered. Did the three children’s aid societies that placed youth in the Barrie home conduct visits as required by regulations seven days and 30 days after placing children? What did Expanding Horizons and the societies share with one another about placing four youth, two of them with a history of violence, with a novice foster parent?

Expanding Horizons paid $4,500 last year to become a member of a group of private service providers called the Ontario Association of Residences Treating Youth. On the association's website, it said the company cared for kids who were emotionally disturbed or behaviourally disordered.

Association executive director Rebecca Harris, asked what it does to verify members' expertise, said: "Members self-identify their areas of expertise and services consistent with their licence."

The association is "not an oversight body," she said. "We trust in the ministry’s oversight and look to the annual licence as a mark that an operator is meeting all standards and providing quality care."

Expanding Horizons applied in 2020 to renew for another year its licence, which in the meantime remains in effect until the ministry completes an inspection, The Fifth Estate has learned.

VI.

David Roman’s time at the Barrie foster home was fleeting, but he left a large impression.

"He's a really funny guy and he’s caring … him and I got close.… He made you feel welcome. He made me feel at home," Evan said.

When 16-year-old Nick arrived, coming straight from juvenile court, he had nothing but what he was wearing, so David lent him clothes.

After David's death, the children's aid society sent Nick and Evan to live in a mental health treatment facility but police ordered therapists not to allow them to talk about what they had witnessed, the youth say.

"It’s in my head forever now," Evan said. "It's hard for me to talk about it now because I had to deal with it all by myself for the longest time."

Asked by The Fifth Estate about what the foster youth claimed, the treatment facility and Barrie police declined to comment.

"As the matter is still before the criminal courts, I will not be providing an interview," Barrie Police Chief Kimberley Greenwood wrote in an email.

Nick wishes he could have talked sooner about what he saw.

"I needed to get everything out. And they just wouldn't let me," he said. "There [are] times that I do think about it and I just break down in tears."

Evan can’t fall asleep at night until about 6 a.m., and when he finally dozes, he has a recurring nightmare, one that begins with David’s killing and ends with James coming back and killing him. Jobs come and go because he’s too tired to stay focused. And when he tries to have fun with friends, he often suffers a panic attack.

"I can barely even breathe when that stuff's on my mind," he said. "I used to be afraid of ghosts and monsters. Now I’m afraid of people."

After David's death, Calver started therapy for what was diagnosed as post-traumatic stress disorder, but that therapy soon stopped when Expanding Horizons cut him off from company benefits, his lawyer Michael Warfe said. Calver struggles to sleep, has flashbacks when he sees blood, takes medication to manage anxiety and has suicidal thoughts. He tries to work but has been unable to hold down a job.

After David was killed, no one from Expanding Horizons phoned his parents, they say. When Dvoskina phoned Lo Greco asking him to return David's possessions, Lo Greco apologized, but nothing was returned.

Nick, Evan and David’s parents all say James was a victim, too, because he needed to be placed where treatment was provided. David was killed, they say, because of systemic failure in foster care and grievous conduct by Expanding Horizons.

"They're making money on children," Dvoskina said. "They're taking children in without any consideration if they know how to deal with those children."

After 12 youth in care in Ontario died from 2014 to 2017, all who struggled with their mental health, an expert panel concluded that their needs had been neglected.

"The quality of care was impacted by the capacity, lack of supervision, qualifications, training and education of staff and caregivers,” the panel wrote in September 2018, the same month Expanding Horizons first met with Calver. "Most of [the youth] experienced fragmented, crisis-driven and reactionary [mental health] services and, in some cases, no services at all."

WATCH |A mother grieves her son in a room that’s now a shrine:

Dvoskina and Antonio Roman have left David’s room mostly untouched, a shrine where a mother goes to feel close to her son.

"Our first meeting. A bright star against a dark background. Ultrasonic picture. Your growth is measured in millimetres," Dvoskina wrote as part of what she plans to be a victim’s impact statement.

"I put you in bed for a nap. I leave the room and don’t see you getting out of bed and quietly following me. It is only before I go to the back yard that I turn around and see you. You throw your hands up and shout, 'Good morning!' You are four."

"We are flying on a zipline over the treetops. The wind is buzzing, and I can see you waving your hands; I cannot hear you. Later, when we are in the car heading home, you say: 'Mommy, I felt so sorry for all these people tethered to the ground.' You are 11.

"I kiss you, as always before bedtime, and say, 'Good night, baby. Mama loves you.' You are 15. I want to lose my mind. May the madness wipe off February 19. Let me feel the fear and pain that you felt. My son will never be 16.'

- Watch full episodes of The Fifth Estate on CBC Gem, the CBC's streaming service.