February 5, 2020

It's July 9, 2011, in St. John's, and the rain is coming down hard.

In an otherwise quiet neighbourhood around Portugal Cove Road, the sound of a single gunshot reverberates in the air.

The shot kills a 20-year-old man.

It sends another man to federal prison for the first time.

This is a story about time inside a Canadian institution, and the daunting transition from a cell to the outside world.

I. Eggs are good for you

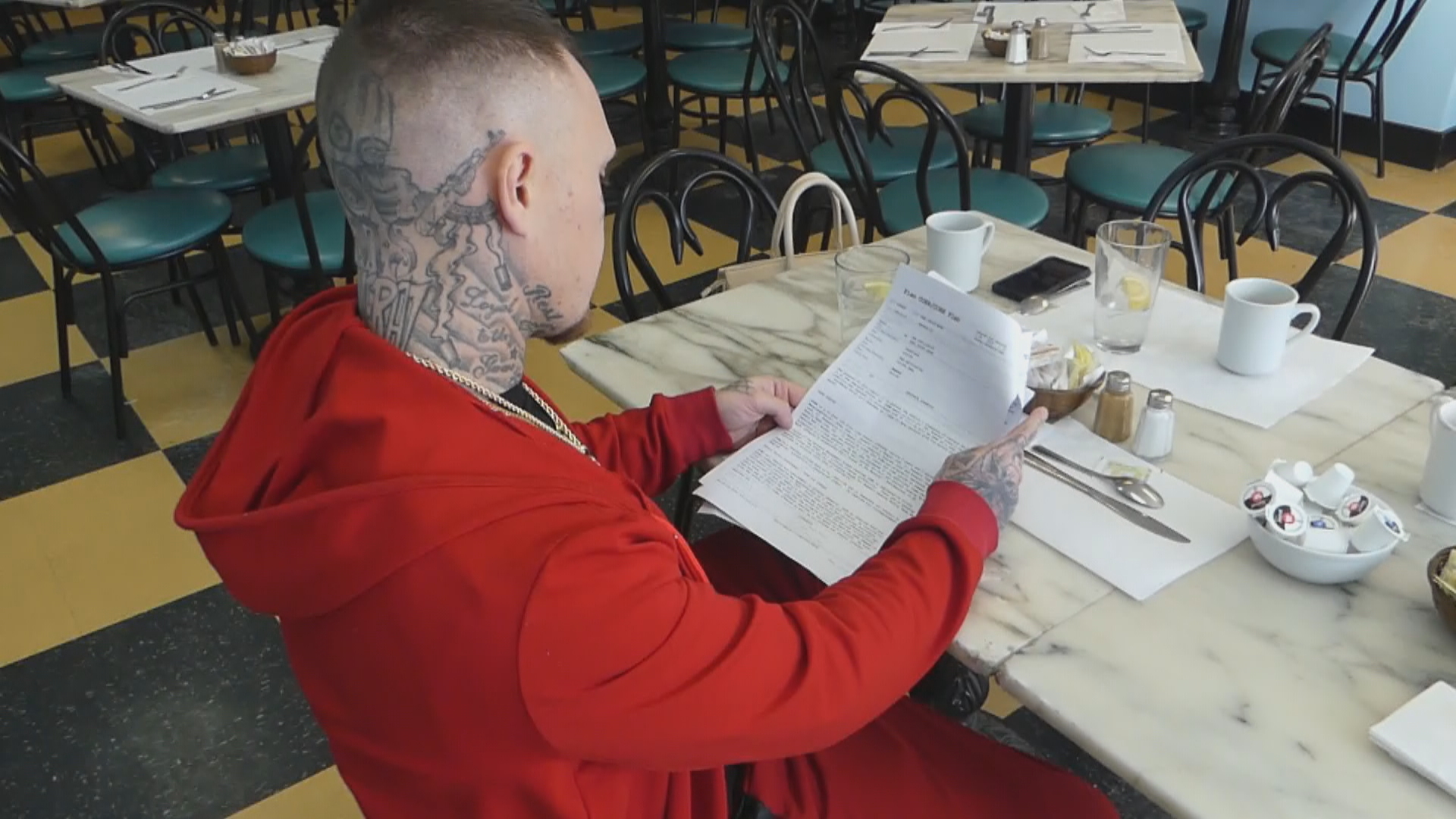

Sitting in a coffee shop in Dartmouth, N.S., Philip Pynn carefully reads over the menu between sips of coffee. Three gold chains and a cross sit heavy on his chest.

It's January 2019, 10 days after Pynn — a notorious crime figure in St. John’s for years, even though he’s still in his 30s — was released from the Atlantic Institution in Renous, N.B., a maximum security prison known for its violence and frequent lockdowns.

It’s been nearly eight years since he fatally shot his best friend.

On this morning, Pynn settles on the breakfast combo that offers the most eggs, and gives the waitress a “thank you” without looking up from his menu.

"There are so many ways you can cook an egg," he says, listing the techniques you use to cook in prison.

"It’s good for ya, right?"

Pynn is on statutory release — a term used by the Parole Board of Canada to indicate when an offender is, by law, ready for a second chance.

In his case, it’s more than just his second.

Despite being incarcerated for nearly all of his adult life, there is nothing foreign or awkward about his interactions with average people in his new home in Dartmouth.

He holds doors for others, cracks jokes with servers in restaurants and makes small talk with retail workers.

Since 2016, CBC News has been in contact with Pynn, a criminal figure who many people in his home province of Newfoundland and Labrador love to hate. Pynn’s sensational 2014 murder trial captivated the province, marked by scandals, twists, Pynn’s shameless comfort in court, and a spotlight that illuminated a way of life in the St. John’s underworld.

For more than three years, he has spoken to us frequently over the phone, and sat down twice for in-person interviews. He’s spoken about prison life, crime, childhood, second chances and rehabilitation.

He’s also talked about his friend Nick Winsor.

Pynn agreed to be profiled as he transitions from a cell — his 2014 conviction marked the first time he was sent to a federal institution — to the outside world.

He is one of more than 14,000 people incarcerated in Canada. The majority will be released at some point in their lives. The hope is that they will be reformed people, for the betterment of themselves and society.

Watch the full documentary Killing Time below

II. A meeting in Springhill

Three years before that meeting in a coffee shop, we met Philip Pynn under very different circumstances.

Springhill is a small Nova Scotia mining town in central Cumberland County. It’s home to famed Canadian musician Anne Murray, and the Springhill Institution, a medium-security prison that sits back from prying eyes off a rural road.

It’s October 2016. Pynn is led inside the prison’s cafeteria. He's ready for an on-camera interview, with outfit changes on hand. He’s carrying a water bottle and takes off his sunglasses before warily shaking our hands.

“There’s never a day that I wake up in the morning thinking, ‘I hate this place,’” Pynn said.

“I wish I did, because I really want to wake up and hate this place. I’m so used to it, I’m almost like a robot to it now … like this is how it is.”

Despite Pynn’s best negotiating efforts, a correctional officer makes him change into institutional blues — a T-shirt — before the camera starts rolling.

Institutional clothing is just part of Pynn’s lifestyle. Decisions are made for him about where he can be and when, what and where he can eat, who he can see.

A frequent inmate at provincial jails in Newfoundland and Labrador, Pynn is accustomed to it.

“I don’t think of myself that I’m institutionalized.… I think I’m institutionally adjusted,” he said with a smile.

“So, I’m 30 years old, I spent about half my life in jail … at least.”

A life without freedom is one Pynn knows well. It is his normal.

Even so, the summer of 2016 was his “best summer yet,” filled with suntanning, friends and ice cream.

Still, he is insistent he does not want to stay in jail.

“I missed out on a lot … a lot of stuff,” he said.

“But that’s the price you pay. You go out, you live this lifestyle and you want to go around and around, and doing what you’re doing and this is what happens. You go to jail, you get back out, you do the same thing. It’s a shitty cycle.”

Since he turned 18, the longest stretch Pynn has had outside prison is 11 months. Even then, he said, there were two weeks in that period when he was put back in jail before being granted bail.

It’s a cycle that Pynn said started simply enough, then culminated like a snowball rolling down a hill that couldn't be stopped. He didn't try and no one was there to stop it.

Steal, jail, breach, repeat.

Assault, jail, breach, repeat.

“It’s hard to rehabilitate people when they’re around a bunch of criminals,” Pynn said.

“I believe that unless you want actual change yourself, no matter what program or what you're doing, it doesn’t make a difference. It ain’t going to make a difference unless you do it yourself.”

The Correctional Service of Canada says about 23 per cent of the inmate population will reoffend — a statistic the federal agency says has dropped drastically from 1995.

Statistics from the federal government for 2016-17 peg the average annual cost of keeping a male inmate incarcerated at $112,640. The annual average cost for incarcerating a woman was $191,843.

The associated cost with having an offender serve a sentence in the community is 74 per cent less than the costs of having a person in custody at a federal prison.

When a person is sentenced in Canada, a judge must consider a number of things: denunciation, to ensure the punishment reflects society’s thoughts on the crime; deterrence; protection of the public; reparation; responsibility; and rehabilitation, to make offenders into productive citizens.

Pynn has participated in numerous programs while in federal prison, targeting inmates who are repeat offenders.

None have appeared to make a large impact, and Pynn insists his accomplishments with programming is never acknowledged.

III. Growing up Pynn

How do you break a circle you were born and bred into?

In the Pynn household, being a criminal is the norm.

It’s what Philip Pynn, the youngest sibling in a blended family, has known since he was a young child, and what he admits he’s good at. With just a Grade 6 education, selling drugs and committing crimes that come along with the trade is easier than putting out resumés.

"One day, I was getting ready to go to school and the door would get kicked in, the cops would be running in with guns and stuff," he said.

"They’re checking your book bag, and after 15 or 20 minutes, they’re like, 'He can go out, he got nothing.'"

Breaking the cycle at this stage of his life will mean breaking family ties, turning his back on old friendships, and rearranging the only life he has ever known.

It also means things like properly learning to read and write.

Through years of interviews, Pynn consistently refuses to blame his parents for his shortcomings, despite being raised in a criminal lifestyle.

“They treated me good. They did. My whole family, my mom and my dad. They did the best they could for us, for our family,” he said.

“And yes they did sometimes, like, sell drugs to make money, but it was to provide for the family. I think of it as, I’m lucky to have a family that would do what they had to do to provide for us.”

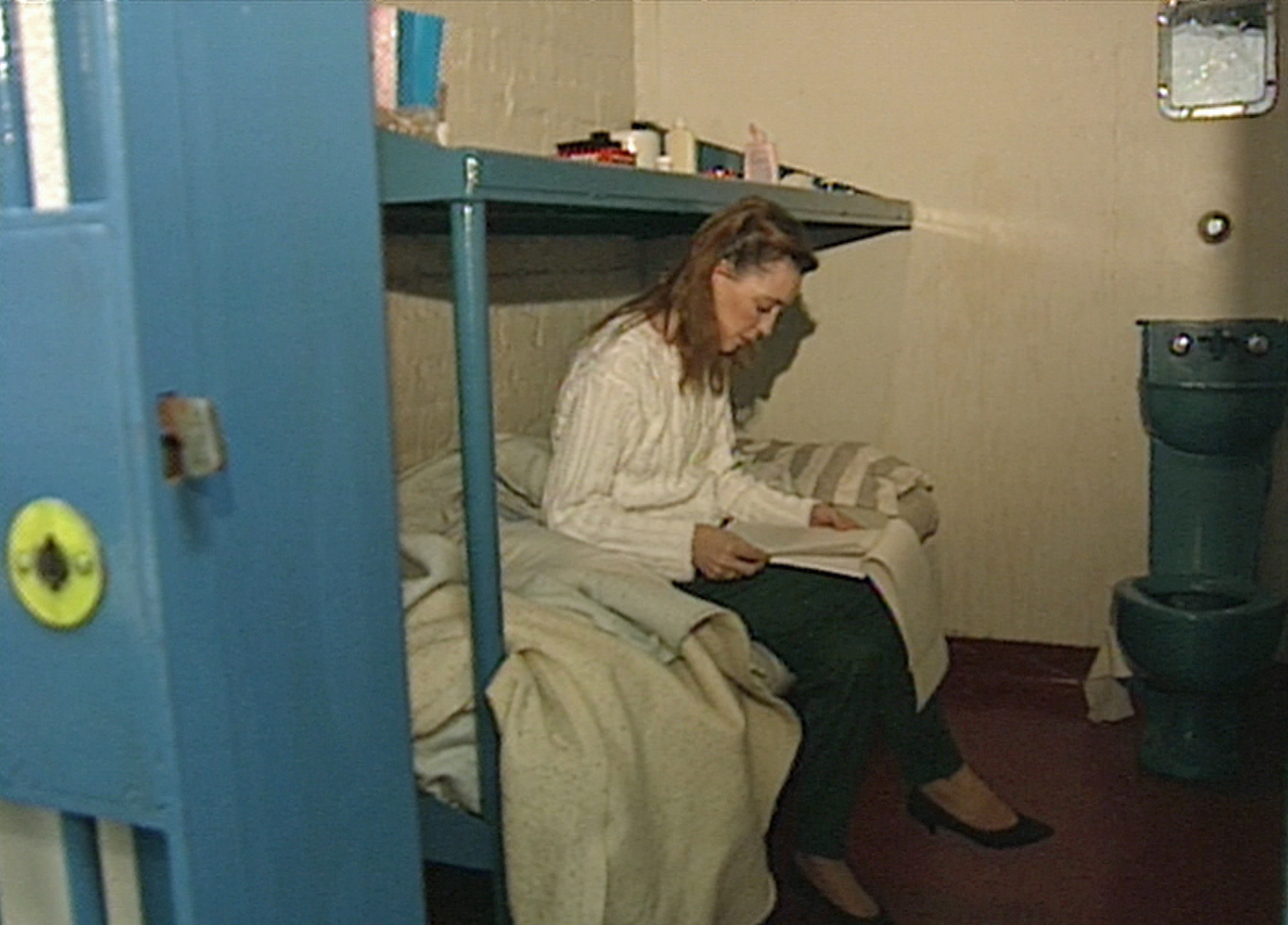

His mother, Loretta Pynn, was once a familiar name on the evening news — when her youngest son was just a child — entering the same courtrooms and sleeping in the same cells that her son would also one day frequent.

Then known as Loretta Clarke, she is believed to be one of the first female armed robbers in the province. Reporters covered each court appearance of the pretty and petite Clarke, as salacious details emerged about a brazen daylight robbery in July 1993 at the TRA wholesale business in St. John’s. Clarke drove the getaway car.

Clarke begged to stay at the St. John’s lockup, a place designated for short-term stays, instead of the women’s jail in Stephenville on the other side of Newfoundland.

In 1995, prison officials gave in. She was allowed to stay in St. John’s near her children.

Christmas colouring sheets were taped along the cold, painted brick cell that Loretta Clarke called home. Bright red, purple and green crayon scribbled inside the lines of a Christmas scene cartoon.

“To Mommy from Philip, Felicia and Dad.’ Dad helped them colour it,” Clarke told CBC News at the time. “Now, this one here you can see he made in school, with a bit of help from the teachers.”

Before the TRA robbery, the family had a different life. Philip Pynn says they lived in a middle-class home in Elizabeth Park, a residential neighbourhood in Paradise.

His parents had a second-hand car lot and restaurant but lost it all, he said, when his father — also named Philip — failed to pay taxes.

“At the time, my dad, he drank heavily. But I guess he was going through his own problems, losing his house and business,” Pynn said.

“We went from living in Paradise in a nice home, and we ended up living on Barachois Street in a rundown house.”

There was no routine in that home, no structure, no guiding hand. His mother was in and out of prison; his father was fighting alcoholic demons. His grandmother was trying to do her best.

“I was in the mall just stealing food, hungry and stupid stuff like that. I got picked up for, I think it was theft, and then it just escalated,” Pynn said.

“Once I got in the system, there was a breach [of conditions]. Basically, I had a curfew, and I’m young — no one’s there telling me to come in.”

Years ago, Loretta said she wrote a letter to all of her children, apologizing for being a friend, not a mother. For being someone who introduced and fostered a criminal culture. For not making her children go to school.

Pynn, however, said his situation is one of his own making.

“I’m 30 years old. I put myself in the situations,” he told us during that 2016 interview.

“I was introduced to it, but at some age, I was old enough that I could have changed it if I wanted to.

“I don’t like putting blame on other people. I think if I do something, that’s on me.”

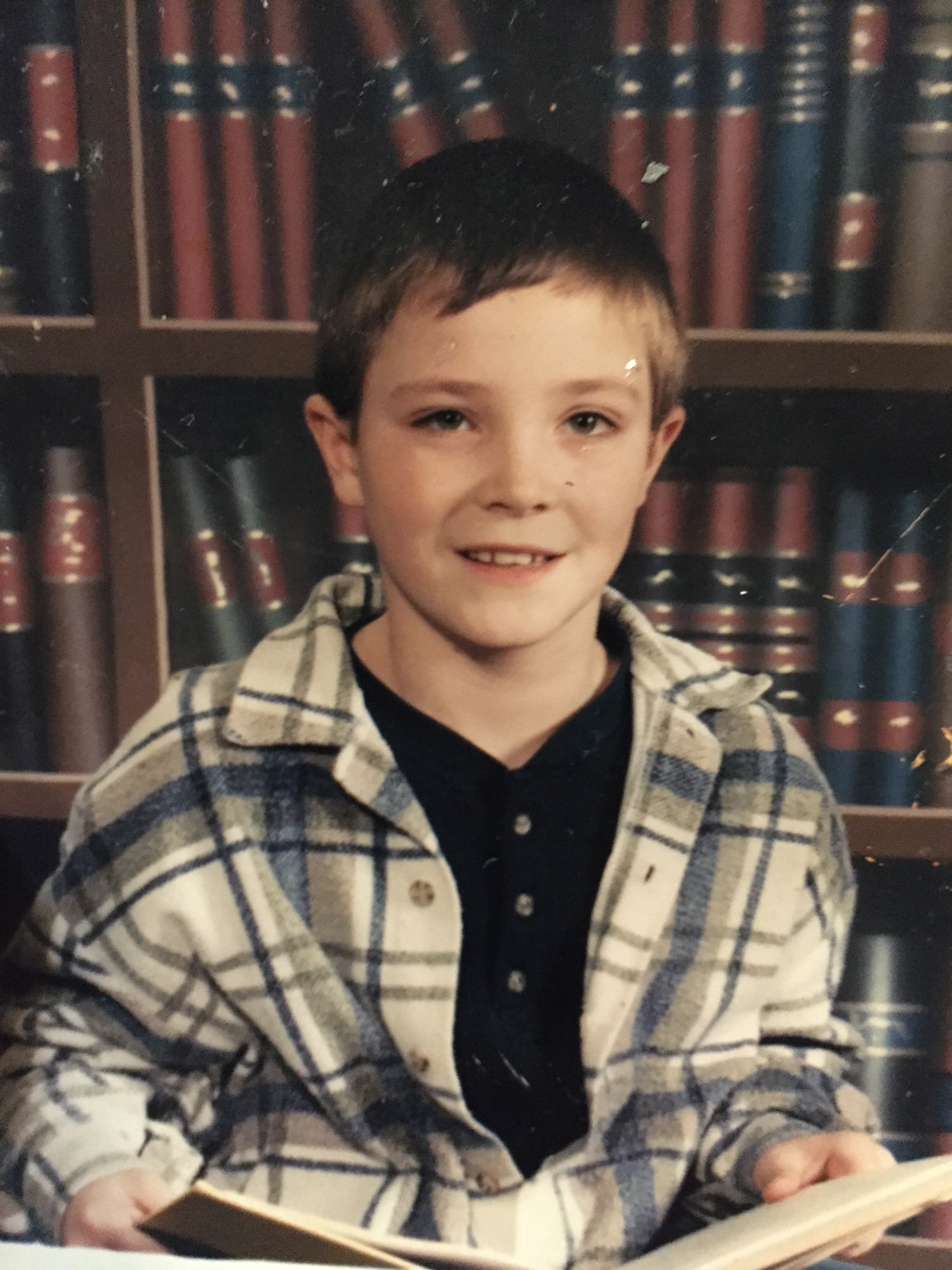

By the time Grade 7 rolled around, Pynn had already been suspended multiple times and had a reputation — one that had started before he ever got into the school system, a byproduct of family notoriety. He took part in fights. He brought weapons to school.

He wasn’t forced to attend classes and when he did, he found it hard to keep up. Pynn had undiagnosed dyslexia.

“I couldn’t read a lot of stuff and I couldn't participate in a lot of stuff,” he said.

“Basically my way was, I’d sooner get expelled than figure it out. It was too hard at the time and once they realized I was in and out of trouble, [teachers] understood this is the road he’s going down and that’s it.”

IV. Making a friend in juvie

By the age of 12, Pynn was in the juvenile correctional system, and he liked it.

He later made friends, like Nick Winsor, a younger boy.

"He was one of the best friends you could have," Pynn said.

"He was a really, really loyal person. He was really fun and he was talented."

At 20, Winsor’s life would be taken away with a single shotgun blast to his neck.

Photos of Winsor as a thin, young man show sharp, dark eyes and hair to match, with tattoos on his face and neck. His lips were pressed together in a straight line.

The words "Trust No One" were tattooed in cursive writing across his two forearms. Spiderwebs spread out from both elbows.

“I would literally to that day … still to this day do anything for him and he would have done the same for me,” Pynn said.

“That’s the type of guy he was. If he was your friend, he was your friend. There was nothing he would not do for you.”

Pynn says he takes the blame for his death.

“It was my fault. It was on me. It was my situation,” Pynn said, mumbling. His head shakes side to side, his eyes close to slits.

“He wouldn’t have been there for no other reason than he was a good friend and he was there with me.”

V. What went down on Portugal Cove Road

For the first time since his trial and sentencing, Pynn is revealing his story of what happened the night he, Winsor and another man (the Crown believed it was Lyndon Butler, who would stand trial with Pynn) went to a home on Portugal Cove Road in the east end of St. John’s with a loaded shotgun. These are details that were not disclosed during his 2014 trial.

Pynn said he wanted to take back a gold pendant and chain — or its worth in cash — that his friend sold for him when Pynn was still inside Her Majesty’s Penitentiary.

Billy Power, who lived at the Portugal Cove Road house, would tell a jury he bought the jewelry for $5,000 years earlier, and that it was melted down.

“Once I grabbed a hold of it, the gun went off, it hit my friend. It hit Nick.”

Grainy black and white surveillance video from outside Power’s house showed what happened before Winsor’s death.

Three hooded men go to the back door of a house. Billy Power comes out. Four people walk inside a detached garage. Moments later, a single shot rings out. Screams quickly follow.

Only three people run out.

Watch surveillance recorded at 271 Portugal Cove Road on July 9, 2011

Pynn says the gun’s purpose was to scare, not shoot.

“The gun was brought there with me. It was an intimidation-type thing, like ‘Hey, I want my f--king money.’ Once the gun came out, the guy just grabbed a hold of it, [Billy Power] just grabbed it,” Pynn said.

“There was a struggle, and obviously once you got your hand on it.… Once I grabbed a hold of it, the gun went off, it hit my friend. It hit Nick.”

Pynn has regrets — but perhaps not the regrets one might expect.

“He hit the ground and you could tell, all life went out of him. I knew he was dead,” he said.

“I needed to get out of there and I felt … and still feel to this day horrible about [that] because he’s my friend. I felt like I left him there on the floor bleeding out. He was dead. But I left him there. And that affects me.”

A short time after the men ran away from the garage, Billy Power’s then partner and her daughter made the grisly discovery. Their blood-curdling shrieks are heard on the surveillance video.

For that, Pynn says he feels guilty, too.

VI. Bombshells in the courthouse

Three years later, amid unprecedented security, a dramatic trial played out at Supreme Court in downtown St. John’s.

The public would learn that not one but two well-known St. John’s lawyers were in relationships with the Pynn family. A Crown prosecutor, Nick Westera, exchanged information for a relationship with Pynn’s older sister, Felicia. It was said to be of a sexual nature.

Pynn himself was captured by police at his lawyer Averill Baker’s house, but not before the two fell onto the ground in a passionate kiss. Their audience: an entire Royal Newfoundland Constabulary tactical unit wearing riot gear.

People who normally would have no interest in the court of law were showing up to watch the show. Each day provided insight into the criminal underground of St. John’s, and no one knew what twist would come next.

Pynn didn’t shy away from the cameras. He relished them, wearing fancy suits and shiny shoes. He would turn and look at each camera, making sure every journalist got their shot.

In the end, a jury convicted Pynn of manslaughter — not the second-degree murder charge that prosecutors had argued for. Lyndon Butler, his co-accused, was acquitted.

The person driving the getaway car has never been charged. Pynn says he has no intention of giving them up.

Pynn was sentenced to 8½ years in a federal prison, minus the time he had already served in HMP, some of which had been spent in segregation.

Extra time was tacked on for yet another headline-grabbing crime: a February 2014 prison riot that broke out during Sunday service at the HMP chapel.

Pynn and other inmates attacked Kenny Green, another well-known St. John’s criminal, who at the time was awaiting trial for murder.

Elderly members of the Salvation Army clergy watched in horror as Green was attacked with homemade knives and shards of a church pew that was used as a spear.

VII. ‘If I get more time, I’ll be pissed’

In Canada, inmates serve two-thirds of their federal sentence before they are eligible for statutory release.

When we spoke to Pynn in October 2016, he had a year and a half left until reaching that mark. He admitted that the unknown — life outside of prison — was scary.

“I never, ever worked a job before until I came to federal prison. But I made money, I did really good over the years. But I made money over criminal activity,” he said.

He wasn’t wishing away his time. Thinking about the days left inside makes the wait that much longer.

Pynn was, however, thinking of who he will be and what he needs to do once he is released. He plans to visit Nick Winsor’s grave and sit down with Winsor’s mom. Until that happens, he said, he won’t begin to forgive himself. He had tears in his eyes.

“Am I going to break the cycle? I’m so deep into it now, it’s just been who I’ve been for so long.”

Pynn was later moved to the Atlantic Institution, a maximum-security prison in Renous, N.B., and was set for statutory release on July 30, 2018.

“Anything can happen in that year and a half. It’s just so hard to depend on that date until it comes,” he said.

“I will be pissed if I pick up more time.”

He picked up more time.

As the days ticked down to his release, Pynn had been in the process of determining which halfway house he would go to. He selected his top three choices, with St. John’s being No. 1 on the list.

But at the 11th hour, police charged Pynn with a crime that had happened a year earlier inside the federal institution.

In July 2017, Pynn took part in a violent four-on-one attack that ended with the victim mopping up his own blood.

Deflated, hardened, but not perturbed, Pynn explained during a phone call that it was simply a crime of necessity that landed him back in trouble.

“I picked up some charges from running up on a PC unit. I ended up assaulting a PC [protective custody inmate] and I got a bit of time for that,” he said matter of factly.

Protective custody is an area of a prison where inmates are kept when there is a high risk of them being harmed or killed by other prisoners. Often, people who have abused children or women are kept separate from the rest of the prison population.

Pynn said if he had the chance, he would do it again.

“That’s just been the routine. We see one of the PCs and we get ‘em, right. It’s just the way it’s been there. It’s just the way it is. Sex offenders, people who checked in off another unit who owed money,” he explained.

It’s part of prison politics, he says.

But suggesting he had to do it didn’t sit well with him.

“I don’t feel like I have to do anything. I’m a grown man, so I make up my mind on what I do. But if you see a PC, we get ‘em,” he said.

Before that incident, Pynn had a history of prison violence. Correctional Services of Canada considers him to be a founder of one gang and an associate of another.

Pynn served 11 separate terms behind bars at provincial prisons between 2004 and 2011. On the inside, he has been slapped with 97 institutional charges for things like possessing contraband, failing drug tests and fighting.

"We are asking this court to have belief that Mr. Pynn can be somebody other than his past."

Pynn pleaded guilty to the assault on the PC inmate. At a sentencing hearing at Miramichi provincial court in December 2018, his lawyer urged the judge for leniency.

"As a child, you're not supposed to worry about where your next meal is going to be. Mr. Pynn, being raised that way, turned to the only thing he knew, crime, the bad side of his town in Newfoundland.

"We are asking this court to have belief that Mr. Pynn can be somebody other than his past."

Pynn’s girlfriend — whom he met while he was in prison — and her mother signed letters of support for him.

VIII. Released, but not to St. John’s

After serving additional time for the assault, Pynn was released from prison in January 2019. His request to return to St. John’s was denied because of fears over his relationship with some of the men he would encounter in a halfway house.

Instead, Pynn was transferred to a halfway house in Dartmouth, N.S.

It’s a bitterly cold, dry January day, but the skies are clear and winter hasn’t yet done its worst.

Wearing an all-red sweat suit, Pynn saunters out of Jamieson Community Correctional Centre, a halfway house strangely positioned in an industrial area of town.

The outside corners of his eyes crinkle when he smiles. Prison has aged him. Pynn has gotten bulkier, too, and he has new tattoos, including red cherries on his left ear in honour of a friend he met in prison who was shot dead.

Slowly counting on his fingers, Pynn tallies the dead, of people lost to drug overdoses or murder in the time he’s been in jail. The number is more than 10.

“It makes me wonder if I’d be dead too, if I were on the outside,” he said.

Any time Pynn leaves the halfway house, he has to call and let them know where he’s going, including a number of Airbnbs he rents in the day. He pays for them with wads of cash he carries around with him.

Things have changed on the outside, too. He fields numerous calls and flips through new apps and technology on an iPhone, which he has had to learn how to use. There’s Snapchat, Instagram, Facebook and Twitter. When he was last out of prison, he had a BlackBerry and a flip phone.

He has a lot of catching up to do.

“All these people are saying, ‘Hey, what’s up?’ These are friend requests, almost 200 friend requests. I do them almost every day, I confirm them,” Pynn said. He scrolls through dozens of messages and requests.

Some women send unsolicited nude photos. Men wish him well. They’re all strangers.

During his trial in St. John’s, women sent mail to Her Majesty’s Penitentiary expressing — at times, in detail — their interest in him, seemingly unperturbed by his criminal lifestyle. While in federal prison, he spent countless hours on payphones speaking with different women.

Despite a strange sense of hero worship that comes to him through social media, scores of people comment with vitriol and scorn on online stories about Pynn’s cascade of activities in the justice system. In the court of public opinion, most always focused on retribution over rehabilitation, Pynn is a villain.

His tattooed skin and nonchalant attitude are seen as flying in the face of the justice system there to convict him, time and time again.

“To each their own. I don’t really care. They don’t know me.… The way I look at it, for everyone who hates, I got a lot of people who loves,” he said.

“I done my time for it, I served my time for it. People are going to have to get over the fact that I’m out.”

Prison comes with its own routine. For Pynn, working out was part of that. In Dartmouth, he continued to go to the gym near his halfway house in an attempt to stay out of trouble.

“Keeps me in a good headspace. Keeps me in a good routine, which I feel like I need, a bit of structure,” he said between breaths as he lifts weights.

“I’d like a job that involves fitness, I know a lot about it. I find when you work out, it keeps you in a good headspace, it keeps your mind clear, you eat healthy, you feel better right?”

With 10 days of freedom, Pynn insisted he hasn’t done anything remotely criminal and that he had no desire to do so.

The Parole Board of Canada, however, doesn’t share the faith that Pynn has in himself.

The board has very little positive to say about Pynn, in fact, and has deemed him a high risk to reoffend.

"The board views you as an individual who strictly adheres to a pro-criminal way of life," a July 2018 decision reads. "Your values and lifestyle are deeply entrenched and you maintain associates with similar values."

The parole board lists Pynn as having a propensity for violence, troublesome associates and an attitude "requiring a high need for improvement."

In a decision released on January 2019, the board was skeptical.

"This criminally-ingrained behaviour has continued throughout much of your repeated incarceral terms, including your current federal sentence," the board wrote Jan. 11, 2019.

"Your offending pattern has been persistent since the commencement of your criminal career."

Pynn insists people — average people — shouldn’t be afraid of him. Not anymore. His targets are targets for a reason, he said.

“Let’s be real here, the people that I allegedly done stuff to and are involved with, they’re no angels,” he said.

IX. The ankle monitor

Unlike other men at the halfway house, Pynn has been ordered to wear an ankle bracelet to monitor his whereabouts, and to ensure he doesn’t enter two specific areas of Halifax and Dartmouth that are said to be associated with gang activity.

Pynn appealed the decision and says it’s a poor solution to a problem that should have long been solved.

“If the system [isn’t] working for people and it’s not integrating people into society, look at that before they look at, 'Oh he’s released into society, now he’s a danger, so we’re going to put a bracelet on him, put him on restrictions,’” he said. His voice has become angry. “When you just had eight and a half years of my time to do something with me!”

Intelligence officers in prison say Pynn was an associate of what’s called a security threat group operating inside the Atlantic Institution. STGs are essentially prison gangs that have been identified as threats to prison officials and other inmates.

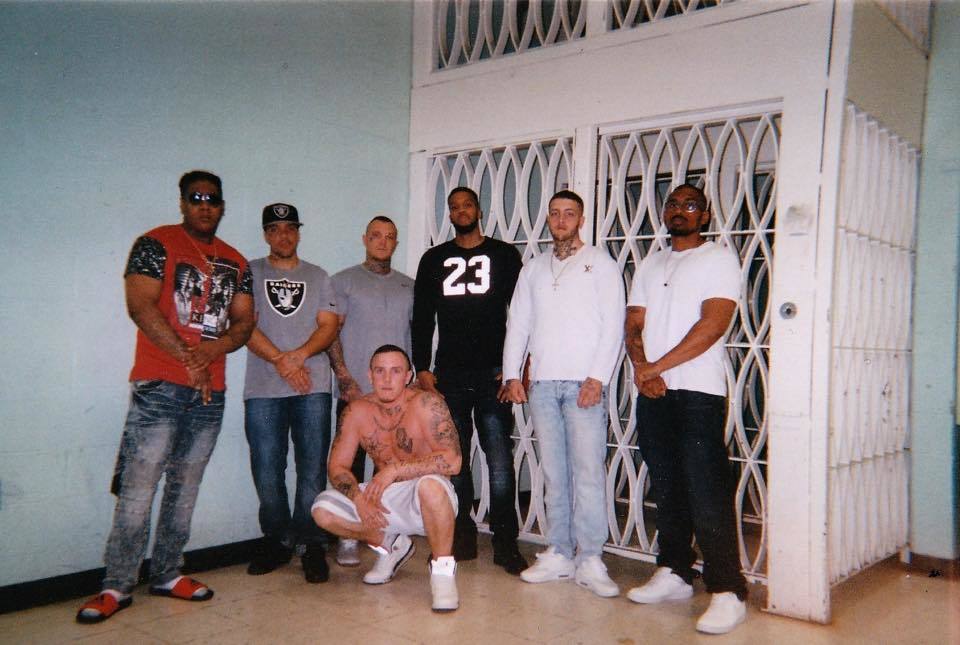

“They’re saying I’m the founder of St. John’s Mob Squad and they’re saying I’m affiliated with RNS — which is Real N--ger Squad. So therefore, they’re saying I’m not allowed in them areas because they’re heavily populated there, so therefore they’re going to put a bracelet on me to make sure I don’t go in them areas.”

While the Correctional Service of Canada has identified St. John’s Mob Squad as a prison gang, local jail officials and police in Newfoundland do not. At least they didn't, when the group first made headlines in 2014.

Pynn insists he isn’t part of the RNS gang, despite having a large RNS tattoo on the back of his neck. He also insists he’s not part of the St. John’s Mob Squad, despite having SJMS tattoos on his arm.

“Would you have a Crips tattoo if you weren’t a part of the Crips?” I ask.

He laughs. “Yeah, you’re right.… I wouldn’t.”

The tattoos, he summarizes, are merely a sign of his friendship among fellow inmates. Not menacing. No, a simple sign of kinship.

The principle of having an ankle monitor when no one else does may not be the real reason for him not wanting to wear it.

“It throws off the outfit and the swag,” Pynn says to his friend Ty Borden, with whom he was incarcerated in Renous.

“You wear your skinnies [skinny jeans] and then [the ankle monitor] is hanging out. The worst part is having to charge it. I have to have it for 90 days.”

The two sit in Pynn’s rented Airbnb in Halifax, which appears to be some sort of seniors' complex. Pynn says he pays money for Airbnbs nearly every day, even though he can spend only so much time out of the halfway house in the day and must sleep at the correctional facility at night.

The source of his cash is questionable, but he flatly says that he “did well” while in prison and before.

Ty Borden is one of the individuals with whom Pynn is not supposed to associate. Borden is also alleged to be an associate of RNS and participated in the July 2017 assault.

Cutting contact with people like Borden will be one of Pynn’s biggest challenges in attempting rehabilitation.

“I’m sure some people would lose respect if I went totally clean and cut everyone out and stuff. Yeah, they’d be pissed. Why wouldn’t they?” Pynn said.

“You want to go and smarten up, cool? But why cut me out of my life? That ain’t me. I’d never do that personally. I think when you’re down, that’s when they need you the most. “

Pynn was one of the first people Borden met when he went to Springhill in 2015. The two have been friends ever since.

“He’s not some angry, crazy killer like they make him out to be, right?” said Borden.

There’s a barber shop in town in the basement of a clothing store owned by a man who has himself been to prison. His barbering skills were recommended by another convict.

There’s a single mirror and barber chair in the windowless basement. A large television screen mounted on the wall is sectioned into quadrants showing the view from surveillance cameras positioned around the building.

“Rehabilitation, it’s not as easy as they put it out to be,” the barber says, flicking his electric razor along the sides of Pynn’s head.

“They’re not giving me much opportunity to be successful,” Pynn answers.

“Set you up to fail,” the barber mumbles.

“You gotta play the game, you gotta do what you gotta do. Better off where I am than where I was.”

In the next several months, Pynn plans to get his driver’s licence and find a job.

He had two jobs lined up, but they fell through for reasons beyond his control, he says.

“[My friends] asked me straight up, ‘What’s your plans? Are you getting out, are you being good? Are you going to end getting in trouble?’” Pynn said.

“I said, ‘I want to try whatever I can to stay out.’”

The men offered him work in the construction field, but are still under the watch of parole officers themselves. Pynn is encouraged to be around them, but they have been warned by their parole officers to stay away from Pynn, an alleged gang founder and member with little chance at rehabilitation.

Greed has played a big role in Pynn's past downfalls. He admits it. At the time of his release, he is 33 years old, and he wants all the things other people his age have worked years to achieve. Working at a minimum-wage job pales in comparison with the cash he could make in the drug trade. Easy, quick money.

Resisting the urge may be too strong to overcome, but Pynn maintains he does want to legitimize his life, and toys with the idea of one day opening a business.

“I’m in the best headspace I’ve been in. I’ve been in [prison] a long time. I’m a lot older, I matured a lot. I actually think about stuff before I act.

“Now I’m out here and I’m going to do good no matter what it is, no matter what job it is starting off until I get used to it.”

X. Behind bars again

A month later, in February 2019, Pynn was rearrested.

The Parole Board of Canada cited numerous reasons why Pynn’s statutory release was revoked — social media posts, a failed drug test, associating with the wrong people.

"You were said to be struggling with your special condition not to associate with criminally active individuals, as you stated many of your friends you had met while incarcerated were residing at the halfway house with you, or were known to be involved in a security threat group," the board's decision states.

During his release, there were "numerous concerns regarding your social media presence," the decision added.

"Your parole officer (PO) observed public social media posts you made displaying your gang-affiliated tattoos; you also appeared to be associating with questionable individuals.”

Months later, reached by phone back at the Atlantic Institution, a familiar voice picks up.

His excuses for rearrest were lengthy and varied but he eventually admitted, "It's obviously my fault I'm back in jail."

“They got me now until they got me. I’ll be here until my time is up,” he told me.

“They warehouse you. Lock anyone in a cell 23 hours a day and see how they do.”

XI. ‘She’s in jail, too’

Back in St. John’s, Loretta Pynn has reset the countdown clock until her youngest is released.

Her fridge is a collage of photos. Almost all are of Philip, including a kindergarten graduation photo, where he’s wearing a blue gown and clutching a white diploma.

She sleeps with a stuffed animal her son had delivered to her while he was in HMP. It hasn’t been washed in years. If she were to put it in the washing machine, she says, it might not be dry by bedtime, and she won’t sleep without it.

She’s in the kitchen of her St. John’s apartment, on the phone with her son, who called from a prison payphone to discuss when she can visit him.

“So you want me to hold off on sending in the applications today? Sweetheart, I just think I should see you first. She sees you every day,” she tells him. Her legs are crossed, her eyes fixed forward.

Loretta Pynn’s daily routine revolves around her son, even though he is provinces away.

“They don't know Philip at all. Philip is nowhere near what people say he is — he's not a monster. Far from it,” she said.

Philip Pynn admits that in his mother’s eyes, he can do no wrong.

As for regrets, Loretta Pynn has a lot.

“I take the blame. I own that. For their lives. They probably would have been better educated,” she said. “I think I tried to be more of a friend and I should have been a better mom.… You know, I never ever punished Philip.”

What her children lacked in discipline, she tried to make up for it in material things.

“I got called into school and asked if I could, if they could take my son's rings and chains off his neck until after school,” she said.

“I'm not going to dress them down. This is what they're going to wear if they like it. And no one's going to tell me any different.”

Bedtime for Loretta is the precise time federal prisons shut down for the night, and inmates are in their cells.

She wouldn’t dare sleep before then.

“When I’m in jail, it’s like she’s in jail, too,” Pynn said.

XII. Waiting

Philip Pynn’s federal sentence will expire in May.

If death, violence and second chances aren’t catalysts for change, a young girl back home may be.

“I have a daughter. I owe it to her to do it for her. The thing that has stopped me in the past is some of the lifestyle I was living, I didn’t want her growing up around that,” he said.

“No kid deserves to grow up around this or be anywhere near this. And she didn’t deserve to grow up around that because the way people grow up affects them, right?”