January 31, 2021

WARNING: This story contains graphic content.

One afternoon in 2015, word went out to staff at Peter Nygard's palatial seaside compound in the Bahamas. A meeting between Nygard and a senior politician had the green light.

A well-oiled machine comprised of staff members who knew what to do when encounters like these were planned sprang into action. Cash was prepared by accountants. Vehicles were readied. The former Canadian fashion mogul was informed it was time.

The massive wooden gates at the sprawling estate named for its owner, Nygard Cay, slowly rose to allow a convoy of cars to leave. Nygard would often meet powerful and influential people in the Bahamas under unusual circumstances.

"I know of the instructions for the accountants to get cash for [Nygard] to take to his private meeting after hours," said a longtime employee, whose identity we are protecting. He still fears retribution from Nygard, and those close to him.

- Watch "Peter Nygard: The Secret Videos" on The Fifth Estate and listen to CBC Podcasts' new series about Peter Nygard, Evil By Design.

The employee, who worked at Nygard Cay in various roles for nearly eight years starting in 2008, was responsible for directing staff to make arrangements for the meeting. For him, it was a familiar scene.

The former employee, and three other sources, describe attempts by Nygard to forge connections at the highest levels in the Bahamas where he is accused of operating an elaborate sex trafficking ring spanning more than two decades, involving dozens of young women and girls, an investigation by the CBC podcast Evil By Design and The Fifth Estate has found.

"I felt broken, like a piece of me was taken from me," a woman known as Jane Doe No. 1 said in an interview.

She is one of 10 original women who went public in a class-action lawsuit with allegations against Nygard exposing for the first time what was going on behind the gates at Nygard Cay.

According to the suit, filed in New York last February, she was 14 years old when Nygard raped her in 2015.

Since then, more than 70 additional women have stepped forward with similar allegations. In December, U.S. authorities charged Nygard with nine counts of sex trafficking, sex assault and racketeering involving at least dozens of survivors. He was arrested in Winnipeg on an extradition request.

The CBC investigation, involving interviews with 19 women who say they were raped by Nygard and many more conversations with lawyers, private investigators, politicians, local activists and former employees, reveals an elaborate effort to cultivate influence with prominent decision-makers in the Bahamas, silence victims and block anyone who tried to expose him.

The tactics include payments to senior politicians and police officers in the Bahamas, drugging and holding young women and girls against their will, an alleged campaign of violence against a group of local people who stood up to him and an aggressive legal offensive aimed at the CBC that began investigating reports of sexual misconduct involving Nygard in the Bahamas as far back as 2009.

Nygard denies all of the allegations, and says they are lies and part of a conspiracy meant to destroy his reputation spearheaded by his former neighbour in the Bahamas, billionaire Louis Bacon.

For the women who told CBC they were assaulted, Nygard’s methods created a climate where it seemed impossible to come forward against someone who appeared so powerfully connected on the Caribbean island, keeping his alleged campaign of rape and sexual assault in the Bahamas a secret for more than two decades.

"The government of the Bahamas gave him a sanctuary in which to operate a criminal sex trafficking ring," said Lisa Haba, one of two U.S. lawyers who is suing Nygard on behalf of survivors.

"He uses power, his influence, his brand, to show the world that I am Peter Nygard, and I control everything I touch."

I: ‘A corrupter of men’

In 1984, Nygard purchased a modest bungalow on a breathtaking piece of property on the western tip of New Providence island in the Bahamas.

Known as Simms Point for more than 400 years, the piece of Caribbean paradise is surrounded on both sides by the sparkling Atlantic Ocean and is perched at the edge of a wealthy gated community called Lyford Cay.

Nygard, the Finnish-Canadian founder of a Manitoba-based multimillion-dollar fashion empire, had fallen in love with the Bahamas.

"We'd been living in Winnipeg … with 40 below [temperatures]. And I'd never been to a warm country in my life," he told a Bahamian TV production in 2008.

"I saw this beautiful place with beautiful white sand, these beautiful people here. And I said, 'That's for me.' "

Over the next 20 years, Nygard constructed a 2.4-hectare estate consisting of a series of tree house-type buildings made of rock and glass that jut out over the sea. It has 12 bedrooms, a berth for a 25-metre yacht, pools and jacuzzis carved out of stone, a 21-car garage, tennis courts, volleyball courts, a disco and a movie theatre.

As you approach the compound, tall wooden gates, edged with barbed wire, are under constant surveillance by a series of cameras. From above, a soaring glass roofed structure shaped like a star, known as the main hall, anchors the centre of the property while giant stone lions guard a turquoise lagoon and a vast white sand beach dominates the southern edge of the estate.

While the natural beauty is striking, it’s a stark contrast to the decades of pain and damage Nygard is accused of inflicting on so many there.

The entire compound is styled after a Mayan temple.

"I've been very careful not to build a Beverly Hills house in the Caribbean," Nygard said in a 2005 legal deposition.

"It's finally a dream come true that I can do for me and that I can share it with a lot of my friends, the Bahamians."

Indeed, Nygard made influential friends in the Bahamas.

In a 1992 letter Nygard sent to a local up-and-coming-politician, he offered a reminder of his "significant" $45,000 pledge to the politician’s party and asked for a series of favours.

The politician at the time was the minister of agriculture, trade and industry in the ruling Progressive Liberal Party, or PLP.

Nygard wrote that he’d already been "given approval" to extend his property, and that he now wanted to make it a "legal fact." He also asked to officially change the name of his property from Simms Point to Nygard Cay in time for an upcoming shoot with celebrity television show Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous.

"Obviously, this whole world is based on one hand helping the other," wrote Nygard. "And you know that I am prepared to do whatever is in my capacity to help out the Bahamas and the PLP party and of course yourself in any way I can."

That politician was Perry Christie, who would go on to become prime minister of the Bahamas in 2002.

Fast forward to 2011. Christie, now leader of the opposition, was preparing a campaign for a second run at prime minister.

He took time to fly to Winnipeg in July to attend the wedding of Nygard’s daughter. He celebrated there with Nygard's friends and family and the mayor of Winnpeg at the time, Sam Katz.

Nygard "is a significant personality in the Bahamas, known for his philanthropy, a contributor to those who are in need," Christie said in a speech at the wedding, and then he went on to describe a favour he provided to Nygard.

"He was having some difficulty with his residency. I was introduced to him and facilitated the granting of that certificate that enabled him to be a resident in the Bahamas."

Later that same year, Christie travelled with Nygard to Las Vegas for a conference. Video from that trip shows Nygard introducing a series of young women to Christie in a hotel suite after a meeting. A photo, obtained by CBC News, shows Nygard and Christie seated between two young women in a restaurant. One of the women has a rolled-up wad of cash in her bra.

In 2012, Christie won the election, becoming prime minister for a second time. A video from election night shows Nygard celebrating at his office in Times Square in Manhattan. A camera was rolling while he was talking on the phone.

"Isn't it wonderful, we won, we won, we won. One of the best nights of my life," he can be heard saying.

"I never thought I would get so involved with politics of all things. Let alone be the key instrument in making it happen, for Christ's sake. As you know, I’ve got millions in this."

WATCH | Peter Nygard reacts to Perry Christie's 2012 win in the Bahamian election:

In the days that followed, another video shows Nygard hosting a group of government ministers from the PLP at Nygard Cay, boasting again about how he supported them.

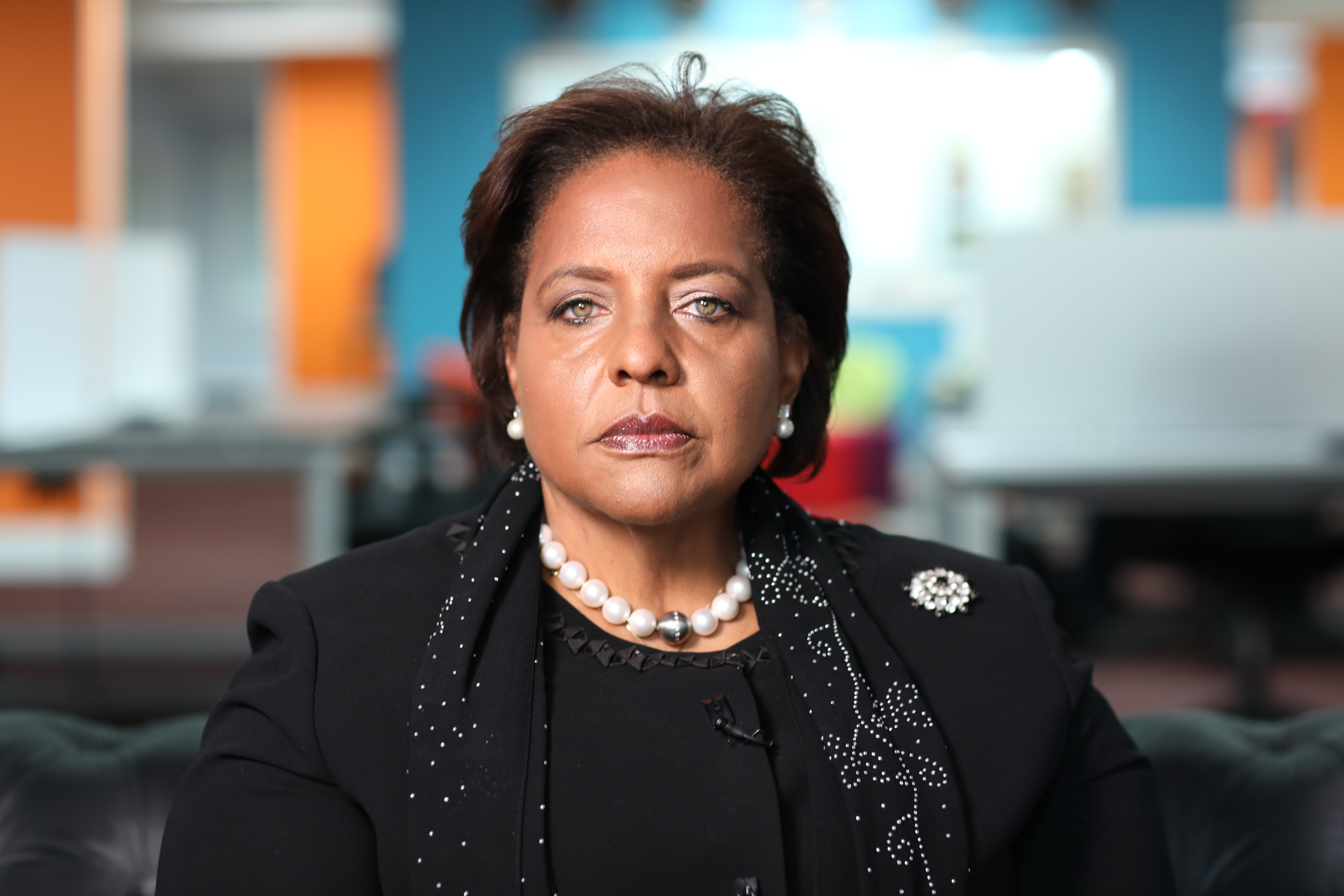

"It's a video that many Bahamians would have found was absolutely despicable," said Loretta Butler-Turner, the former leader of the opposition party, the Free National Movement.

She describes Nygard as someone who "uses their money and influence to get people to help them achieve whatever it is that they're hoping to achieve or to try and turn a blind eye to whatever it is they're doing, a corrupter of men."

II: 'She panicked and started screaming'

While Nygard and Christie were celebrating their election victory in 2012, CBC was facing an aggressive legal campaign aimed at suppressing reporting about Nygard’s sexual misconduct in the Bahamas.

The Fifth Estate team had been sued twice in civil court by then, and then in 2013 Nygard charged us privately with criminal libel in connection with a 2010 documentary by The Fifth Estate that reported he had psychologically abused employees and exposed allegations of sexual misconduct at his home in the Bahamas.

If found guilty, the maximum penalty for The Fifth Estate team was five years in a federal prison.

"This Nygard saga really does show how powerful private individuals can use the criminal justice system to silence and punish anyone, including members of the press, who are critical of them," said Jamie Cameron, professor emeritus with the Osgoode Hall Law School in Toronto.

"I don’t see this as anything other than a scandalous and utter abuse of the criminal justice system."

The original CBC investigation into Nygard began in 2009. Over the next 14 months, The Fifth Estate spoke to dozens of former Nygard employees.

The team also dealt with a series of strange incidents. A vehicle was parked outside the home of a member of the team, with a man watching for three days and a strange computerized voice on our cellphones that said someone was recording our calls.

While there is no way to know if Nygard was connected to these events, another incident can be traced to the legal team representing him at the time.

Nygard’s lawyers provided CBC with a series of emails from Nygard employees and business associates, praising their boss and friend.

"I'm proud to call Peter Nygard a true friend in business and personal relationships," one email said.

CBC could see the email originated from the individual's account, but when he was contacted, he was adamant he never wrote or sent it.

"It’s from me?" he asked, with surprise. And then he laughed. "I'm going to phone my office and find out what the hell is going on here."

The 2010 Fifth Estate investigation focused on what several sources described as a highly sexualized atmosphere at Nygard’s home in the Bahamas, including a tradition for holding weekly gatherings, what Nygard called pamper parties.

They were described as a chance for Bahamian women and girls to relax and have fun. Staff coaxed women to attend the parties, saying Nygard was searching for models.

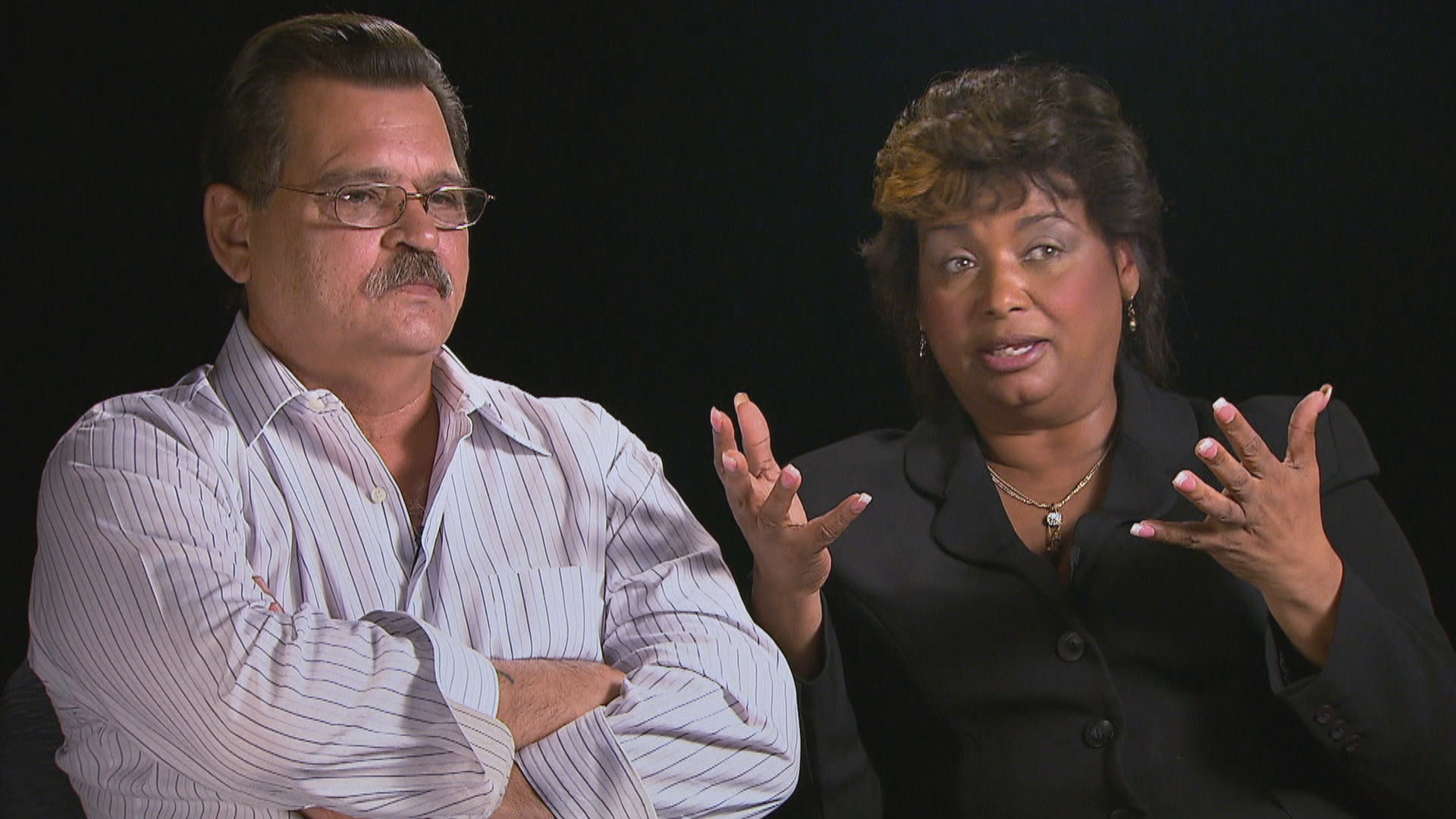

Michelle May, who managed properties at Nygard Cay in 2003 with her husband, told The Fifth Estate back in 2010 that "the pamper parties had nothing to do with trying to find a model."

"It was basically to procure women so [Nygard] would have the pick of the litter to decide who he would bed for the night."

At the time, Nygard denied the allegation.

One of the people invited to a pamper party in 2003 was a 17-year-old from the Dominican Republic. Her name was Maribel Rodriguez.

"She could hardly speak any English. She thought she was coming to be a model," said May.

Three sources told The Fifth Estate something happened to her late one night that frightened Rodriguez.

"She panicked and started screaming and crying and she ran and she actually ended up finding us," May said.

CBC sent a letter with the allegation to Nygard to get his perspective.

Through Nygard’s lawyers, CBC received a sworn statement from Rodriguez saying her time at Nygard Cay was "pleasant and fun" and that all of the men were "real gentlemen," including Nygard. The lawyers also threatened criminal prosecution if the story proceeded.

CBC broadcast the story in April 2010, including the allegation that something happened late one night at Nygard Cay that frightened Rodriguez.

In an effort to block the CBC investigation in the Bahamas, Nygard had already launched lawsuits in Winnipeg and New York City. Next, the CBC found itself the target of an elaborate undercover investigation, in an attempt to undermine our reporting, with no effect. It was followed by a copyright case and a civil case for defamation. In 2011, Nygard launched his fifth legal attack, a rare criminal case against the CBC in Manitoba.

While our investigative efforts had begun, for the first time, to peel back the truth about Nygard in the Bahamas in 2010, it was many years before there would be more reporting about sexual misconduct in the Bahamas.

"[The criminal libel case] creates a pretty serious risk of placing a chill on journalists and members of the press who are seeking to hold public figures accountable for their actions," said Cameron.

In the meantime, a battle between Nygard and his billionaire neighbour in the Bahamas over Nygard’s attempt to expand his beaches by digging up the seabed was escalating and would eventually reveal something far more serious than environmental damage.

III: ‘Our car was firebombed’

It’s 2 a.m. on a cool July evening in 2013, when a car is spotted rolling slowly past the home of a well-known preacher in Nassau, the capital of the Bahamas. It circles the block. As it rolls by a second time, two men get out and throw a flaming object into a car belonging to Rev. C.B. Moss.

“Our car was firebombed,” Moss said. “We were threatened. Our office was broken into. It was frightening but it didn't deter us … we were not going to be intimidated.”

Moss had teamed up with an environmental group called Save the Bays, which was taking on Nygard and his effort to expand his beachfront. Nygard was dredging sand from the seabed and piling it around the edges of his property, creating a large swath of beach where none had been before.

Over 12 years, Nygard had expanded his property from 1.2 hectares to nearly 2.4.

"It's totally artificial," Joe Darville, chairman of Save the Bays, said recently, pointing to the vast white beach while bobbing on a boat slowly circling Nygard's now-deserted property.

In 2010, the Bahamian government ordered Nygard to stop dredging and return the area to its former state. Then, in 2012, the political party Nygard had been supporting, the PLP, came into power.

Nygard's friend, Perry Christie, was now prime minister.

By 2013, Nygard still had not followed the previous government's order. Save The Bays, backed in part by his neighbour Louis Bacon, decided to sue in an attempt to force Nygard to comply.

"We had to fight against not just him but we had to fight against the government … who gave him carte blanche," said Darville.

"He knew how to buy people. He bought out politicians."

WATCH | Joe Darville recalls fighting to stop illegal dredging at Nygard Cay:

Over the next several years, the fight wound its way through the courts in the Bahamas. The battle became bitter and public, spilling onto the streets. Bahamians held protests attacking the group taking on Nygard.

"The abuse was virulent on the radio, on the TV, in the press, in social media," said Fred Smith, legal director for Save the Bays.

Then, one day, Smith said, he was physically assaulted by a group of men at a beach near Nygard's estate.

When he and others probed deeper into who was behind the protests and violence, two local men confessed, swearing affidavits in a court case claiming Nygard had been paying them to threaten members of the group.

"You can soon work out who is the real deal and who is not," said Damian McLoughlin, a former detective with Scotland Yard who assessed the threat posed by the two men who said Nygard hired them.

"I have dealt with informants, I have dealt with undercover work, I have dealt with murders, contract killings and serious people.... They were knocking on the door of being up there. They are serious, very intimidating, very streetwise, very well-connected."

Added Smith: "It got nasty enough for Mr. Nygard, according to our allegations, to hire very dangerous men to kill us."

Those allegations have not been tested in court and Nygard denies them.

By 2017, a Bahamian court slapped Nygard with a $50,000 fine for violating a court order to stop dredging, and threatened him with jail time if he didn’t pay.

Three months later, with the legal battle over the beaches still raging, the PLP government lost power to another party, the FNM.

"The public and the people around Nygard ... started to see that the law could actually work," said Smith, noting that's when individuals with potentially damning information about Nygard began to come forward.

"A few people started to share information about women being abused at Nygard Cay, sexually."

By late 2019, Nygard was back in the news. Six women had gone to Bahamian police and accused him of rape.

The CBCs investigation into Peter Nygard was about to be back in high gear.

IV: 'There would never be an official police report'

In December 2019, the CBC got its first glimpse at convincing evidence Nygard had been raping and sexually assaulting young women in the Bahamas for years, including videotaped statements. It took three days to review the material gathered by Smith and others.

Meanwhile, in the Bahamas, women raped by Nygard were ready to tell their stories, along with several former Nygard employees.

“As time went on, I realized it wasn't really a job, it was just a giant whorehouse,” said Richette Ross.

Ross, who began working as Nygard’s personal massage therapist in 2009, would eventually become a witness to much of what happened behind the gates of Nygard Cay, including Nygard’s well-known pamper parties.

She said if girls and women attending his parties wanted to leave, they often weren’t given a choice.

"I can remember a Bahamian girl going up to Nygard's room. She didn't want to have sex with him and she managed to get out," she said.

"She was naked and she ran straight to the gate and she tried to climb. And his bodyguard came, and he dragged her down the fence. And he carried her back."

Ross said staff also often drugged the women Nygard wanted to have sex with.

"If a female says no, workers would literally drug her and get her prepped for when Nygard is ready to go up with her. The bartenders would usually slip roofies into the females' drinks."

Two other women confirmed they saw white powder at the bottom of their glasses at Nygard parties. And four others interviewed by CBC News believe they were drugged before Nygard raped them.

"He started pushing on me. And I said: 'You have to stop, stop.' And like I said, feeling the way I felt, it was more like I was [trying] 100 per cent, but my body was feeling otherwise," a woman known as Jane Doe No. 3 told CBC News.

WATCH | Jane Doe No. 3 describes what happens when she met Peter Nygard when she was 15 years old:

She is suing Nygard for raping her in 2011 as part of the New York class-action suit. She was 15 years old at the time.

She was invited to a party at Nygard Cay by a female employee who was recruiting young women in the poorer neighbourhoods of Nassau.

"I have never been on that side of the island. So it was amazing,' she said.

To get to Nygard Cay, you first need to pass through the gates of Lyford Cay. It’s a community of more than 400 hectares along a peninsula on the western end of the island that’s been home to millionaires and billionaires since the 1950s. It was founded by famed Canadian race horse breeder and business tycoon E.P. Taylor and has been home to the Bacardi family, famous for its vast spirits empire, and actor Sean Connery.

An invitation to a part of the island inhabited by the world's uber-rich was too much for many from around Nassau to resist.

"For them ... they probably don't have running water inside," said Doneth Cartwright, a lawyer in the Bahamas who took many of the initial statements from young women accusing Nygard of rape.

"Or their parents couldn't pay the light bill. They were probably living in darkness. And you get invited to go to where the rich and famous live. You're not going to turn that down."

Many who attended parties at Nygard Cay describe seeing powerful and influential Bahamians in attendance, including politicians and police officers.

Cartwright said this made a strong impression on the women who went there, especially those who said they were raped.

"For them, it was fear. Seeing this very powerful man was so very well-connected, both politically and socially. How do you go against him?"

This is backed up by several former Nygard employees, including the staff member who worked there in various roles for eight years. He said political figures in the Bahamas attending parties also regularly received money from Ngyard employees.

"They know once they come there for any meeting, cash is a thank you for this and an incentive to do more," he said.

"I have seen them get cash in hand and cheques, and instructions for bank transfers to be made with the accountants."

One of Nygard’s former accountants in the Bahamas, whose identity CBC is also withholding because she still fears repercussions from Nygard, said she was instructed to pay out hundreds of thousands of dollars to several key political figures over her five years working for Nygard.

When she made the payments, she said it was the only time Nygard told her not to ask for a receipt. And she was never told what the money was for.

"I never asked him because I wasn’t supposed to know," she said.

"You can make a fair assumption that they were for bribes or payments to various people."

Former Nygard massage therapist Ross said she, too, personally facilitated payments, in one case using creative methods.

"There was a situation where Mr. Nygard had us order ... fish. And he had them thawed inside the kitchen. And he had me [and two other people], here in Nassau, stuff the fish with about $150,000 in cash, U.S.," she said.

"After we stuffed the fish, we brought them back down in the bags and froze them. The next night, me and the two gentlemen, we went to this particular parliamentarian’s house to deliver them."

A 2018 report from a local watchdog group revealed Bahamian citizens consider government officials the second-most corrupt public institution in the Bahamas. Only the police are considered more corrupt.

"We have confidence that [police in the Bahamas] will... harass you if you're a minor or a regular citizen, we have confidence that most days they're probably sitting down in their office getting fat and not on the road," said Nahaja Black, the host of a Bahamian call-in radio show that focuses on current events.

"But what we aren't confident in is justice."

The CBC investigation found local police officers also regularly receiving cash payments at Nygard Cay.

"The police officers used to come on a daily basis for envelopes, but Mondays would be the biggest day because that's the payout day for the week," said Natasha Codner, who began working in an administrative role at Nygard Cay in 2003. It was also her job to invite young women and girls to parties.

"We always deal with cash transactions and no cheques because [Nygard] said he don't want nothing tied to him."

Ross said she, too, made payments to senior police officers.

To back up her allegations, Ross provided CBC News with three months of bank statements from 2016. There are five deposits from Nygard's parent company, Nygard International, totalling nearly $60,000, followed by several large cash withdrawals from her account.

Ross said Nygard accountants funnelled money through her to make payments to police officers and politicians. She said the payments ensured Nygard would escape scrutiny for any allegations made against him.

"Any female coming in claiming that they were raped or human-trafficked or kidnapped, there would never be an official police report. It would always be something where Mr. Nygard knew where the female lived, where she was either intimidated or paid off to disappear."

Nygard has denied that.

The commissioner of police in the Bahamas didn't respond to an email from CBC News with questions about the role his officers allegedly played in covering up the crimes Nygard was accused of.

Publicly, commissioner Paul Rolle has said he won't comment about the allegations against his officers because of the FBI investigation into Nygard, telling The Tribune newspaper in the Bahamas: "We have not received any complaints about complicity of any officers of the Royal Bahamas Police."

Christie, the former Bahamian prime minister, denies there was anything inappropriate in his relationship with Nygard.

"There's no equivocation about my commitment to integrity," he said in a phone interview with the CBC. "And so I just want to be able to say it clearly, as strongly as I possibly can to you. I have no fear of any investigation into my conduct in my public life. Full stop."

In 2019, the group that was taking on Nygard in the Bahamas invited two American lawyers to assess evidence they had gathered against Nygard. Early the following year, those lawyers launched the civil class-action lawsuit in New York with the first 10 women who said Nygard raped them.

"This was by far the most sinister, the most pervasive, the most perverse and the most violent of all of the trafficking endeavours I've seen," said Lisa Haba, one of the lawyers.

One thing that stood out to the lawyers: Nygard's elaborate recruiting network.

"It's almost like a pyramid scheme," said Greg Gutzler, the other U.S. lawyer representing the women. "You would have this exponential effect of one trafficked woman, she would become a recruiter, she would find four, those four would find four, and then you've got this unbelievable labyrinth of people and everybody kept perpetrating this scheme."

V: 'Good luck trying to get out'

The woman remembers stumbling up the stairs one evening in the early 1990s, her head spinning, as she tried desperately to get back to her room at Nygard Cay. Nygard was at her side, helping her.

The Canadian model worked as a hostess at high-profile events such as award ceremonies.

She and her manager at the time met Nygard on an airplane while travelling for an event, and he invited them to his home in the Bahamas for dinner. Later that evening, her manager informed her he had “traded her” to Nygard, in exchange for sex with three women staying with him.

She said she refused and left the estate, but did go on to work at Nygard Cay off and on for more than five years in the 1990s. Her job was to help organize events and entertain guests at Nygard’s estate.

While she worked for Nygard, she said, he insisted she provide sexual favours to him and she would sleep in his bed at night. But she said she always refused to have intercourse, until one night when he drugged and raped her.

I realized what he did to me.

"In the morning I wake up and I'm face down and I feel like hell," she said.

"I feel like my hair's been pulled, I'm bleeding ... my body hurts, my jaw hurts … and I realized what he did to me."

She is one of three Canadian women interviewed as part of the CBC Evil By Design podcast series who say Nygard assaulted them in the Bahamas. They also either witnessed or experienced methods used to recruit women there.

"I know the other girls used to go into town in the daytime and they were told, like on the beach, go to the disco.... They're recruiting other women," she said.

When they found women, she said Nygard would "reward" them with cash.

Jennifer Gilmore, who was in the Bahamas on a holiday in 1998 after graduating from high school in New Brunswick, said she was recruited by a local tennis coach who was giving her lessons. He asked her if she wanted to meet the "boss."

After a dinner one night at Nygard Cay, Gilmore was left alone with Nygard.

"He was asking me all these questions, and I just started getting a little uncomfortable, but then I also just started feeling kind of fuzzy and numb."

She said Nygard drugged and raped her, too.

Reva Steenbergen was a Canadian model recruited by a musician she knew to travel to Nygard Cay for a photoshoot. When she arrived, she said, she was told by another women that she needed to have sex with Nygard, who said she couldn’t leave until he said she could.

She said Nygard told her: " 'Good luck trying to get out,' and laughed."

"There was a big gate and there were people standing at it, there were guards," she added. "I felt as if I had no choice. I was going to get hurt. Something would happen to me."

Nygard called the women and girls who spent prolonged periods of time at Nygard Cay with him his "girlfriends."

The women CBC spoke to reject that label.

"I have to help [them] swallow the horrific title that is much more true for them, which is sex slave and indentured labourer," said Shannon Moroney, a Toronto-based therapist and expert in sex trafficking who is counselling more than two dozen Nygard accusers, along with members of his family.

"They were trapped by shame and didn't want to go back to their families [because of] financial coercion..… In some cases, that goes on to become a sense of actual ownership of someone and then ultimately resulting in exploitation of that person as a sex slave who may even be asked at some point to begin recruiting others."

Recruitment was only one part of the large and complex machine that enabled Nygard in the Bahamas. The other is the people who helped cover up his abuse.

"We have an international trafficking ring ... with tentacles all over the world with hundreds of people that enabled, helped, and knew about this scheme," said Gutzler.

VI: 'This is crazy, but I have to do it'

Late one night in 2012 at Nygard’s office in New York's Times Square, the company videographer set up his gear to film what he was told would be a "secret" video statement. A young woman sat down timidly in front of the camera.

According to the man operating the camera, he needed to cut several times because the woman was crying and upset. In the end, however, he said she managed to finish the statement, ending with the words: "Nygard was nothing but a gentleman to me."

The entire process, he said, was being directed by a senior Nygard executive.

"This was not a pleasant experience for Maribel. It was very obvious that this statement was written for her and she was reading it and sort of against her will," said Stephen Feralio, the former Nygard videographer who has come forward as a whistleblower.

The woman making the statement was Maribel Rodriguez, who had visited Nygard Cay in 2003 as a 17-year-old from the Dominican Republic.

According to Feralio, following The Fifth Estate's reporting, Rodriguez started working for and travelling with Nygard.

Then one night in 2012 he said he got that call to film the video statement with Rodriguez. Nygard was suing the CBC criminally at the time, after it reported Rodriguez was frightened one night at Nygard Cay. Rodriguez, who denied the event, was his key witness.

When asked why Rodriguez would make that statement, Feralio says he has a theory.

"I remember her saying, like, 'This job is crazy. This is crazy, but I have to do it. I have to support my family,' " he said.

"I know that she would take her pay cheques and send them directly to her mother and her son."

In addition, he said he witnessed Nygard emotionally abusing her.

Feralio provided CBC News with a photo of the interview setup and a copy of the invoice from the job.

The senior executive Feralio said was "coaching" Rodriguez was Nygard’s Toronto-based director of marketing and promotions, Tiina Tulikorpi.

Tulikorpi recalls being present for the statement, but denies it was coerced.

"That's not true," she said. "Maribel Rodriguez would never have done any kind of a statement against her will.

"She was trying hard to pronounce things that she wanted to say in English," she said. "She has a heavy Spanish accent. But ... she would never have made a fake anything."

Years later, in 2020, Rodriguez refused to testify for Nygard in the criminal case against the CBC.

In November, the hearing was officially stopped by prosecutors in Manitoba, who said Nygard had taken too long to make his case.

CBC reached out to Rodriguez through her lawyer, but was told she's not answering questions right now.

Toronto law professor emeritus Cameron said the damage has already been done.

"Think how many potential women would not have been victims if the allegation that you presented in the documentary [in 2010] had been able to lead to charges at a much earlier time," she said.

"He turned the criminal justice system against you, perhaps to prevent allegations coming forward that could have prevented criminal charges coming against him. The criminal justice system shouldn’t allow that to happen."

VII: ‘He was more than happy to grease the palms.'

On Dec. 10, 2020, police officers in Winnipeg set up surveillance teams near a large grey stucco home in an upscale Winnipeg neighbourhood.

Over the next four days, they logged everything they observed, including "large studio-quality photographs of models" in the garage, a female with "grey/blond hair" checking the garbage cans on the street and two sightings of a man in the basement with a “tall forehead and long white hair."

They were there to prepare for an arrest.

According to an affidavit sworn by an RCMP sergeant, the FBI had determined Nygard was a danger to the community, prone to witness tampering, a flight risk and needed to be detained as soon as possible.

"The investigation shows that Nygard's criminal conduct has affected hundreds of victims," the document said.

"Nygard has demonstrated predatory behaviour over a period of decades."

On Dec. 14, the officers moved in and arrested Nygard.

With allegations dating back more than 40 years, Nygard was behind bars facing an extradition request from the U.S.

Nygard continues to deny the charges, arguing his victims are lying as part of his vast conspiracy involving Bacon, his former neighbour in the Bahamas.

For evidence of that conspiracy, he points to allegations made against longtime former employee Richette Ross. According to reporting by The New York Times, two sisters who originally said they had been raped by Nygard in the Bahamas later claimed Ross paid them to lie.

Ross denied the allegation.

"I believe, personally, that they're just running scared," she said.

Ross has also faced criticism for a $5,000-a-month allowance she received to move to a gated community in the Bahamas and for living expenses. It was paid for by the group taking on Nygard, which was partly funded by Bacon.

"Shortly after I relocated, the apartment that I was living in was shot up," she said. "So, if I was still living there, what would have become of me? What would have become of my kids?"

Ross acknowledges she was aware women were being abused at Nygard Cay while she worked there but says reporting it in the Bahamas would have been futile.

"Dealing with the situation with Mr. Nygard is very serious. Because you're not just touching a multimillionaire, you're touching the Bahamas government, you're touching the police force."

In the end, she said she, too, became one of Nygard’s victims. In the lawsuit, she is Jane Doe No. 8.

People who travel to the Bahamas for sun-soaked holidays would rarely encounter this darker side of the islands. Lurking just below the surface, according to a host of studies, surveys and commissions, is widespread corruption and poverty.

Nygard leveraged and exploited those weaknesses, said McLoughlin, the former Scotland Yard detective.

"It comes down to being a white man with money," he said. "Everybody had a hand out and he was more than happy to grease the palms."

"I think it very firmly comes down to government corruption and police corruption."

A few blocks from the beach and luxury hotels in Nassau there is an area referred to as "Over the Hill." It's literally over the hill from the chic downtown boutiques and where the cruise ships would dock almost daily.

Mostly a collection of tiny run-down homes, crammed side by side, stretching almost as far as the eye can see, it's where some of the women and young girls who say they were raped by Nygard called home.

"They never show it to you in the brochure," said Nahaja Black, the Bahamian radio host and social commentator.

"So why would Nygard be here?" she asked. "You can get your women for cheap, your children for cheap."

According to the U.S. indictment. Nygard is accused of using his ties to the fashion industry to lure women and minor-aged girls from disadvantaged backgrounds in the Bahamas and then drugging and forcibly sexually assaulting them.

For the women who came forward against Nygard, it's vindication.

Especially for women like Jane Doe No. 3, who was one of the very first to raise her voice, a decision that led to an avalanche of accusations.

And now she vows to carry on with her life, albeit with an adjustment.

When she was younger, she wanted to be a chef. Today, she wants to join one of the institutions that let her down, along with so many other young women and girls in the Bahamas.

"After the whole situation, I decided that: 'Hey, I want to be a police officer' because I want to protect my friends, I want to protect my family, I want to protect kids on the streets," she said.

"I want justice to be served."

- Watch full episodes of The Fifth Estate on CBC Gem, the CBC's streaming service