July 12, 2020

Jonna Laursen risked everything to make her Canadian dream come true.

The young single mother had given up a life in rural Denmark, fulfilling the goal of her parents to move to this country one day.

By 1980, she was a self-taught seamstress and designer who had just wrapped up stints with two major clothing companies in Canada, including as product manager with Levi Strauss.

On a crisp January morning, she was getting ready to start a new job in Winnipeg, at an up-and-coming company then known as TanJay. It was run by a charismatic businessman with long blond hair, who, like her, had immigrated to Canada from a Nordic country to find a better future.

Then Laursen turned on her radio.

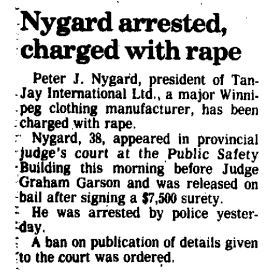

“They said that Mr. [Peter] Nygard of TanJay was charged with raping a girl.… And I was like, what?” she said. “And I was just shocked and I thought, ‘Well, what do I do now?’ ”

On her first day of work that morning, Laursen was assured by her manager there was nothing to the allegations. Nygard was rich, successful and often the target of young women trying to make quick money, the manager said.

And sure enough, within six months, according to a report by the Winnipeg Free Press at the time, the rape charges against Nygard were dropped because the complainant refused to testify.

By then, Laursen said, her new boss had already turned his attention toward her. Over the next 19 months, she said, she was sexually harassed, tormented, screamed at, raped and finally fired.

Through his lawyer, Nygard “categorically denies” the allegations, saying they are “completely false.”

“To publish such a serious allegation which is not true, would be not only negligent, but also grossly unfair and illegal,” wrote Jay Prober in a statement.

Laursen, however, says she struggles with the memories of what she says Nygard did to her, to this day.

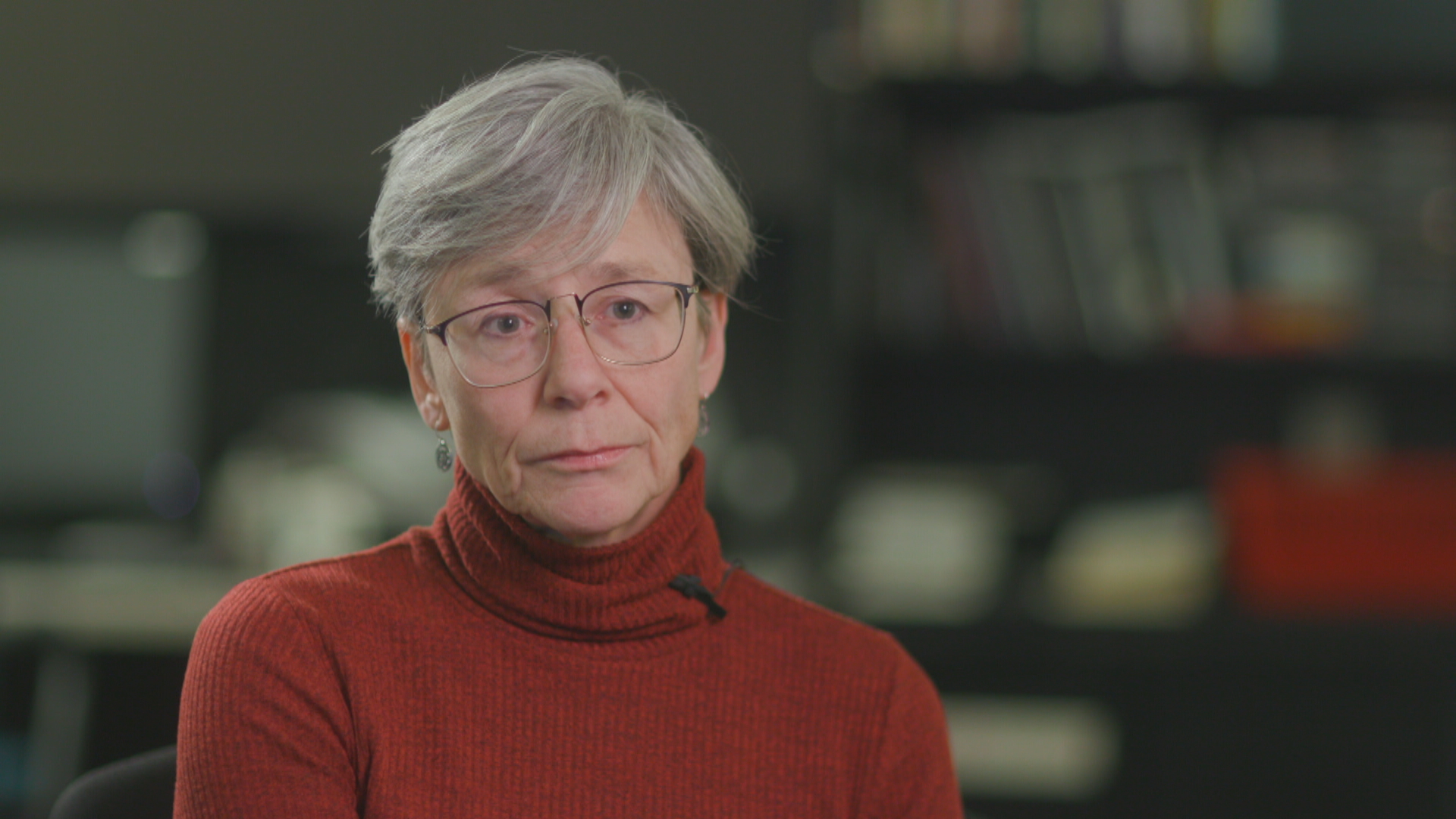

“It still affects me,” Laursen, now 72, told CBCs The Fifth Estate in an interview at her home in northern Denmark, where she is married and retired.

“Making me dirty, somehow.”

Her daughter Zitta, 53, was sitting nearby, hearing the details of her mother’s torment for the first time, 40 years later.

Laursen broke down crying. Her daughter quickly rose to embrace her, quietly whispering in her ear how much she loves her. They held each other and wiped away tears.

“She's so strong,” her daughter said. “She will get through this.”

Laursen eventually moved back to Denmark from Canada in 1982, after several months of failing to find work in Winnipeg. After she was fired by Nygard, she said “nobody dared to speak to me.”

Her Canadian dream was dead.

“Nygard killed it,” she said. “I hope that he's going to pay for some of his bad deeds in his living life.”

At the time, Nygard was a successful clothing manufacturer who would later become one of the 100 richest Canadians.

Today, his offices have been raided by the FBI as part of a sex trafficking investigation and he is accused of raping or sexually assaulting 57 women and girls as part of a civil class-action lawsuit.

CBC News has also spoken directly to 10 women who say they were raped or sexually assaulted by Nygard.

He has since stepped down as the face of his company, which has been forced into receivership.

Apart from the rape charge in 1980, Nygard has never been charged with other sexual offences. None of the civil allegations has been proven in court, and Nygard denies them all.

But as more and more women come forward with stories of harassment and rape dating back years, it begs the question: How did so many of these allegations stay secret for so long?

An investigation by CBC's The Fifth Estate reveals how Manitoba's largest daily newspaper, the Winnipeg Free Press, killed a plan to publish Laursen's story in 1996 and how Nygard's influence assisted in keeping her allegations against him under wraps for more than 40 years.

1. The rise of Peter Nygard

By 1980, Nygard’s Winnipeg-based company was already hugely successful.

He had just expanded his clothing empire into the U.S., earning him a reported $30 million in sales the previous year. He would soon expand again with a new Canadian marketing and sales headquarters in an $8-million building in downtown Toronto.

He had come a long way from his roots, as an immigrant from Finland who arrived in Canada in 1952 as a boy with nothing.

“I realized early in my life that you must set your goals - you’ve got to get your head in the right direction,” Nygard told the CBC in an interview in 1979.

“There are too many hopers and wishers.... You’ve got to really decide in your head, what is it you want to do… and drive yourself towards it.”

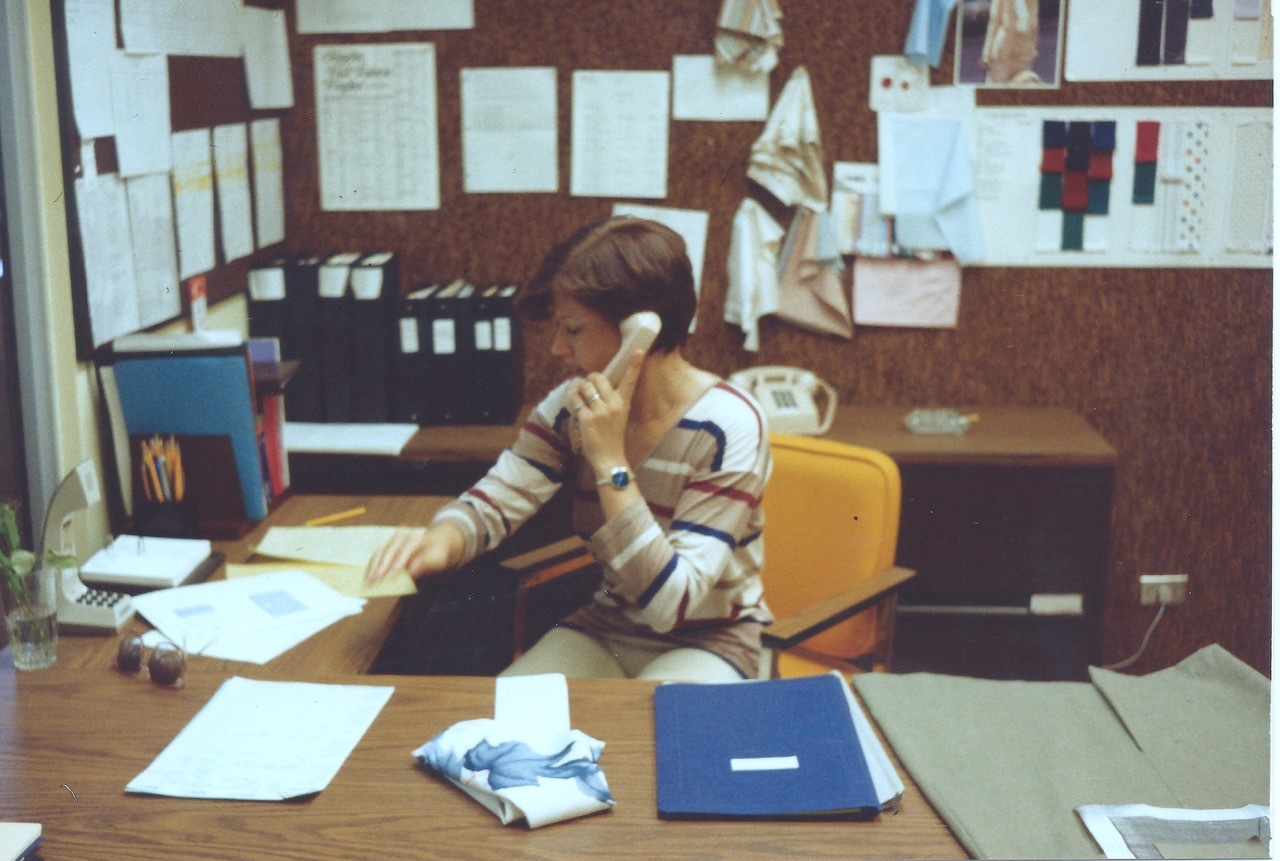

Dale Dreffs was hired as Nygard’s executive assistant in 1980. She was 25 at the time.

“He certainly had a reputation of being this very wealthy, good-looking guy [with] a rags-to-riches story. He was very successful.”

But it didn’t take long for her to regret the decision to work for Nygard. She was exposed to the same kind of harassment that many other Nygard employees would report to CBC, and Nygard would consistently deny, decades later.

One day he called her into his office, which doubled as his living quarters. She said he was sitting on the toilet with his pants down. Another day, she said, while in a meeting, he ran his foot up her inner thigh.

And then there was the yelling.

“I mean, it's frightening, but it's also very degrading,” she said. “I just was a nervous wreck. I was like: ‘What am I doing here?’ ”

Dreffs, too, remembers the rape charge in 1980.

She said Nygard burst into the office that day and asked to borrow the keys to her car. He said he needed to go to court and didn’t want to be seen arriving in one of his signature Chevrolet Excaliburs.

The Winnipeg Free Press later reported the case had been stayed.

The Crown prosecutor at the time told the newspaper he had advised Nygard’s 18-year-old accuser to proceed with the charge, but she had refused.

“We put her on the stand and asked the appropriate questions, but she didn’t want to say anything,” Wayne Myshkowsky was quoted saying at the time.

After the case was thrown out, Nygard once again turned to Dreffs for help. He wanted her to go to police headquarters to collect a box of his belongings that had been held as evidence.

“I can remember [the police officer] ... starts pulling stuff out of the box, a soiled sheet and you know, I just said: ‘Just put it back in the box,’ ” Dreffs said.

“There I am, going out to the public safety building with this box with this writing on it, like ‘Nygard rape case,’ " she said. “I was mortified.”

Around the same time she remembers Jonna Laursen starting with the company. They became fast friends.

“My first impression was she was very competent, and she’s articulate, and attractive. She was very friendly, she was very welcoming,” Dreffs said. “I liked her immediately.”

2. 'He would touch my breast'

Laursen remembers walking into TanJay headquarters on her first day of work and seeing the walls plastered with posters of Peter Nygard.

“He was like an overgrown teenager, in his open shirts and his pointed fingers in the belt loops,” she said.

“I just thought he looked ugly.”

But Laursen, who was initially hired as a merchandising manager, wouldn’t be reporting directly to Nygard, so she figured she would have little to do with the company owner. She was wrong.

She said Nygard approved almost every decision at the company. In the beginning, she said, he was happy with her work.

Before long, she said, she was promoted to head up the design at one of his divisions, overseeing a staff of eight women. Nygard often championed her ideas, but she said eventually his support came at a price.

Laursen remembers doing a presentation one day in a boardroom with Nygard and several other senior executives. Nygard asked her to personally model some of her new designs and then he approached her.

“He would go up and he would touch my breast and [say]: ‘Well, you have to lift this because your one breast is too low,’” she said.

He would also kneel down to inspect the hem on an outfit and look up her dress. She said as time went on, Nygard became “creative” in what he asked her to model, including tight fighting jeans and see-through blouses.

He would also “make sexual remarks to either the upper or the lower part of my body in front of staff members.”

She said senior executives and other staff members often witnessed Nygard’s behaviour, but didn’t say a word.

“There were just 10 men sitting there like they had nothing to do,” she said.

“They must have been stupid if they didn't know.... Nobody has ever put me in such an uncomfortable situation,” she said. “I was shocked.”

Laursen said she endured the harassment because she needed the job. As a single mother living away from her home country, she felt she had little choice but to continue working for Nygard. The pay was good and there were perks, too.

Laursen was also asked to make trips to the Far East, where Nygard sourced fabric and manufactured his clothing.

It was on one of those trips where she says her life changed forever.

3. 'He raped me'

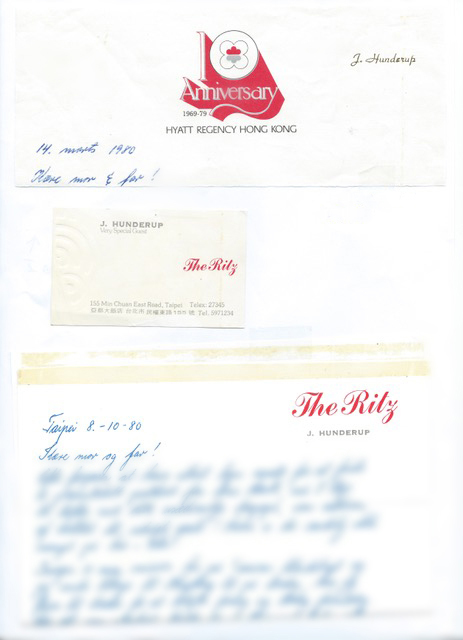

Decades later, Laursen admits the whirlwind itineraries of those trips to Asia are now a blur. At one point, she believed the incident with Nygard occurred in Taipei, and at another point she thought it was in Hong Kong. But the details of what happened that night are seared into her memory.

She remembers being shown her room by the hotel manager. She had been booked into the bridal suite.

“I was just a country girl still, at that time. I'd never seen anything like it. There was chocolates and stationery with my name on it and one room connected to another room and food. I couldn't believe it.”

She noticed a door to an adjoining room. It made her feel uneasy, so she asked the hotel staff to make sure it was locked.

After dinner, she fell into bed exhausted.

In the middle of the night she woke up with a shock.

“There was somebody in my bed. And I woke up and I saw it was Nygard and I was about to say something and he put his hand over my mouth, and he said just don't worry, you are a nice girl, I'm not going to hurt you.

“He raped me.

“I felt dirty. He's a big person. Like I couldn't do anything.... He said: ‘Well, this is just it. Don't go to the police, you won't get anything out of it.’ ”

After Nygard left, Laursen said, she got up from her bed, sat on a chair and cried.

Once again, she felt like she had no choice but to carry on with the company. The next day, she said, she confided in a colleague, a senior executive who was travelling with her.

When The Fifth Estate reached the executive, he said he didn’t remember Laursen telling him what happened.

Back in Winnipeg, she said Nygard never physically assaulted her again, but she was uneasy every time he was around her.

It was around the time when she started a relationship with another company employee that Laursen said Nygard’s attitude seemed to change.

She said Nygard would scream at her relentlessly. She felt she could do nothing right.

In July 1981, she said she got a call to come to meet with another senior Nygard executive. She didn’t see it coming: She said he fired her without an explanation.

Laursen was distraught. She threatened to go to the media and the police and report the rape.

She also disclosed everything that had happened to her friend, Dale Dreffs.

“I tried to console her. She was upset,” Dreffs said.

“She did tell me that she had been convinced that it would be better for her to get a letter of recommendation from them, and you know, so that she could get another job.”

Two Nygard employees visited her at her home later that day, where she said they agreed to change her firing to a resignation. She said she got a letter of reference and $8,000.

The story seemed to end there. Until one day 15 years later when Laursen got a call from a reporter with the Winnipeg Free Press.

4. The Winnipeg kingpins

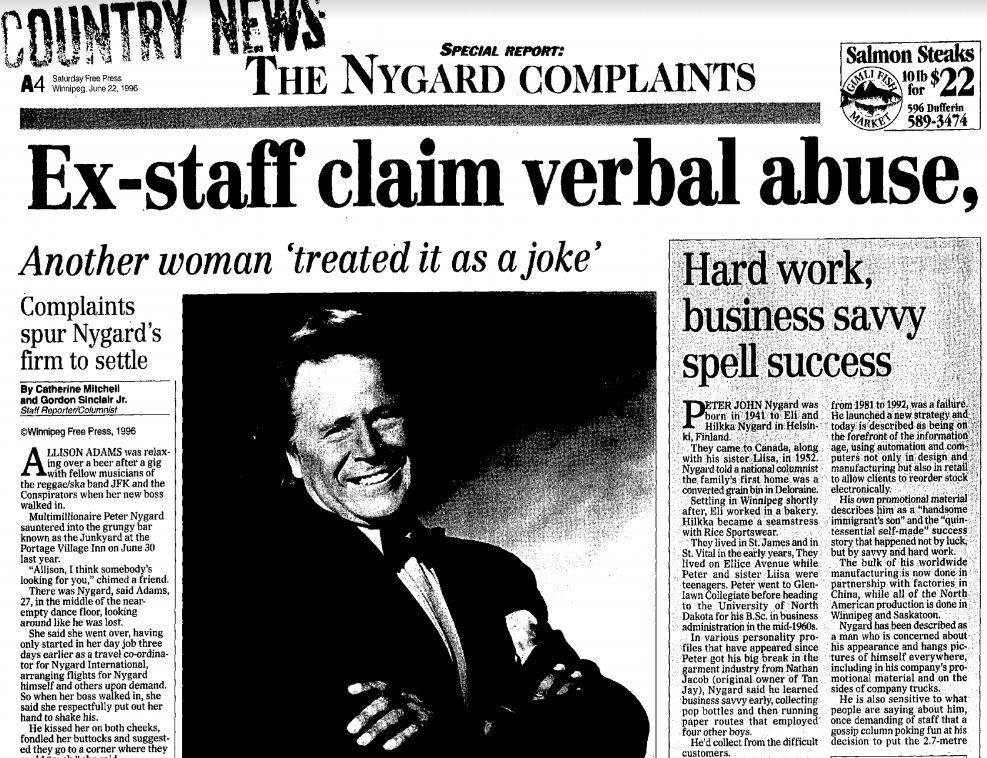

Catherine Mitchell had been working at Winnipeg’s largest daily paper for a decade, when the newspaper received a tip that haunts her to this day.

It came following an expose she and another reporter wrote about Nygard and his alleged treatment of several female employees.

Three of those women had gone to the Manitoba Human Rights Commission with serious complaints about their boss.

According to their 1996 report in the Winnipeg Free Press, Nygard’s company paid about $20,000 to settle three sexual harassment complaints. The complaints against Nygard included adding “skinny dipping” to a meeting agenda, that he “frequently was grabbing himself,” and that he would call a female employee into his office while in a “state of undress.”

“Those who had worked there used the term ‘abusive,’ ” Mitchell said.

“The allegations were that he made sexual comments constantly sort of in a jokey manner ... he would, you know, touch them inappropriately like touching their bodies so they had those complaints and also him fondling himself.”

At the time, Nygard denied the allegations and a spokesperson for his company said it agreed to pay the complainants only because it was cheaper than fighting them, according to the Winnipeg Free Press.

After the story was published, Mitchell said she was flooded with calls, including that haunting tip.

She was told to connect with a woman living in Denmark who said she was raped by Nygard.

Mitchell said Laursen agreed to speak with her when she called her -- and shared a story that Mitchell said was “one of the worst.”

Laursen sent Mitchell a detailed written account, along with several supporting documents, which she has also since shared with The Fifth Estate.

“It was heartbreaking because [she was] a very credible woman, [who] had never launched any kind of suit in the aftermath of the attack,” she said. “She certainly didn’t seek the public spotlight on this.

“Her story had many of the echoes of the stories that we're still hearing, that - you know, hurt by somebody in a position of power, not knowing who I could turn to, who would believe me?"

Mitchell was preparing an explosive follow-up report for the Winnipeg Free Press. Then she was ordered to stop.

She remembers that the newsroom was “solidly behind pursuing the story,” but the publisher was not.

When contacted by The Fifth Estate, that publisher, Rudy Redekop, remembered the incident.

“There was a lot of external pressure from high-positioned Winnipeggers,” or businesspeople he refers to as Nygard “compatriots” and the city’s “kingpins” at the time.

“Those people thought that we were on a witch hunt. I guess they didn't know how to believe that Peter [Nygard] was involved in these things,” said Redekop.

The newspaper reported it had received a threat from Nygard’s company that it would sue, but Redekop said that didn’t affect his decision regarding Mitchell’s story. He also said Nygard never called him directly.

But other members of the Winnipeg business community did. Redekop decided to kill any further Nygard stories.

“You know what, I was not sure that we weren’t just trying to create some sensationalism for Winnipeg. I decided not to continue with it,” he said. “It was a long time ago. Things were different.

“You know what? Maybe we should have proceeded ... but you know, we didn't. The decision was made at the time and we just have to live with it.”

5. 'Completely false'

CBC News detailed Laursen’s allegations in a letter to Nygard’s lawyers.

In response, Jay Prober called the allegations “completely false.”

“There was, of course, never any formal complaints to the police or anyone else and there was never any criminal charge at the time 40 years ago,” he wrote.

“This was likely instigated by those involved in the criminal conspiracy against Nygard.”

Nygard has argued the women who accuse him of sexual assault have been paid to lie by his billionarire neighbour in the Bahamas. Louis Bacon and Nygard have been feuding for more than 10 years, after a property dispute boiled over into a series of lawsuits.

Laursen is not one of the 57 women involved in the class-action lawsuit against Nygard.

Prober warned the CBC that publishing the Laursen’s allegations would be “grossly unfair and illegal” and threatened to pursue the CBC “criminally” if it proceeded.

Another lawyer representing Nygard said his client had nothing to do with the Winnipeg Free Press failing to publish Laursen’s story when she came forward in 1996.

“Mr. Nygard was not involved in any attempt to stop the publication of a story about unreliable, false and malicious allegations by Ms. Laursen about Mr. Nygard,” said Richard Good.

6. 'I ask for some peace'

In 1981, a year after Laursen said she was raped, according to Nygard’s website, he was given an award by the Winnipeg Chamber of Commerce for outstanding Canadian distinction.

In 1986, he was given the city’s community service award.

In 2003, he received the Queen's Golden Jubilee Medal, which was given to Canadians for “contributions to public life.”

Former Nygard executive assistant Dale Dreffs said sadly, it was a different time for women.

“In 1980, there weren’t all the options you have if something like that happens to you now and the attitudes were different.”

Today, wealthy and influential men are starting to be held accountable for sexual misconduct.

A shift began in 2017 when more than 80 women came forward to accuse movie and television producer Harvey Weinstein of sexual misconduct. In February, he was found guilty and sentenced to 23 years in prison.

That’s part of what's given Laursen the courage to finally step forward after more than 40 years.

“I don't get anything out of telling my story, except maybe a bit more peace inside,” she said.

Back in Denmark, her interview is drawing to a close. She is almost done telling her story. Again.

“It's good having my daughter here, as well. I never think that I really told her the details. It's unpleasant. But yet I feel good about her knowing it.”

As the interview ends, Laursen and her daughter embrace once again. Afterwards, Laursen takes a walk by the North Sea. She looks out over the fjord and points to a building in the distance.

It’s the house she grew up in. She’s retired and a grandmother now, living back where her life began.

“I ask for some peace,” said Laursen. “I ask myself for some peace. And breathing space, after all those years.”

With files from Linda Guerriero and Lynette Fortune

- If you have any information, or a confidential tip, to share about this story, please contact Timothy Sawa at timothy.sawa@cbc.ca.