April 14, 2019

Dana MacInnis was in his early 20s when he started abusing opiates, after a knee surgery gone wrong.

“I got access to a large supply of opiates and started to tell myself that it was OK to use just a little bit,” MacInnis says, sitting on a cream-coloured sofa at Vancouver’s Overdose Prevention Society on Hastings Street.

“But it's not.”

About three people die of a drug overdose every day in British Columbia. Three years ago, the provincial health officer declared a public health emergency in response to the rise in drug overdoses and deaths.

Since then, the province has increased the number of safe consumption sites like the Overdose Prevention Society and made overdose-reversing Naloxone kits widely available. Health officials say the changes have saved about 4,700 lives.

But officials and critics alike say more needs to be done.

Provincial Public Health Officer Dr. Bonnie Henry says later this month she will release a report pushing for more bold solutions, like pharmaceutical alternatives to street drugs and de-facto decriminalization.

“This is all about stigma," Henry said.

"And one of the reasons that people use alone and are dying alone is because they're afraid of getting a criminal record, and losing their job, and losing their family, and all of the other things that go with that,” Henry said.

Those on the front lines, like MacInnis, say they’re hopeful the crisis will end — as long as the province keeps advancing new solutions.

“People have to be bold enough to take the steps that are needed to end the crisis,” MacInnis said. “If they don't then it will go on and on.”

Over the years MacInnis, 50, has been in at least three car crashes and two workplace accidents as a journeyman carpenter.

He now uses fentanyl. MacInnis says he has tried to quit it three times, but the severe cramping and convulsions of withdrawal were too much to bear. So he takes his chances buying drugs on the street.

Still, he considers himself lucky.

“I don't really feel for myself, I feel for other people that don't have access to all the facilities that I have,” he says.

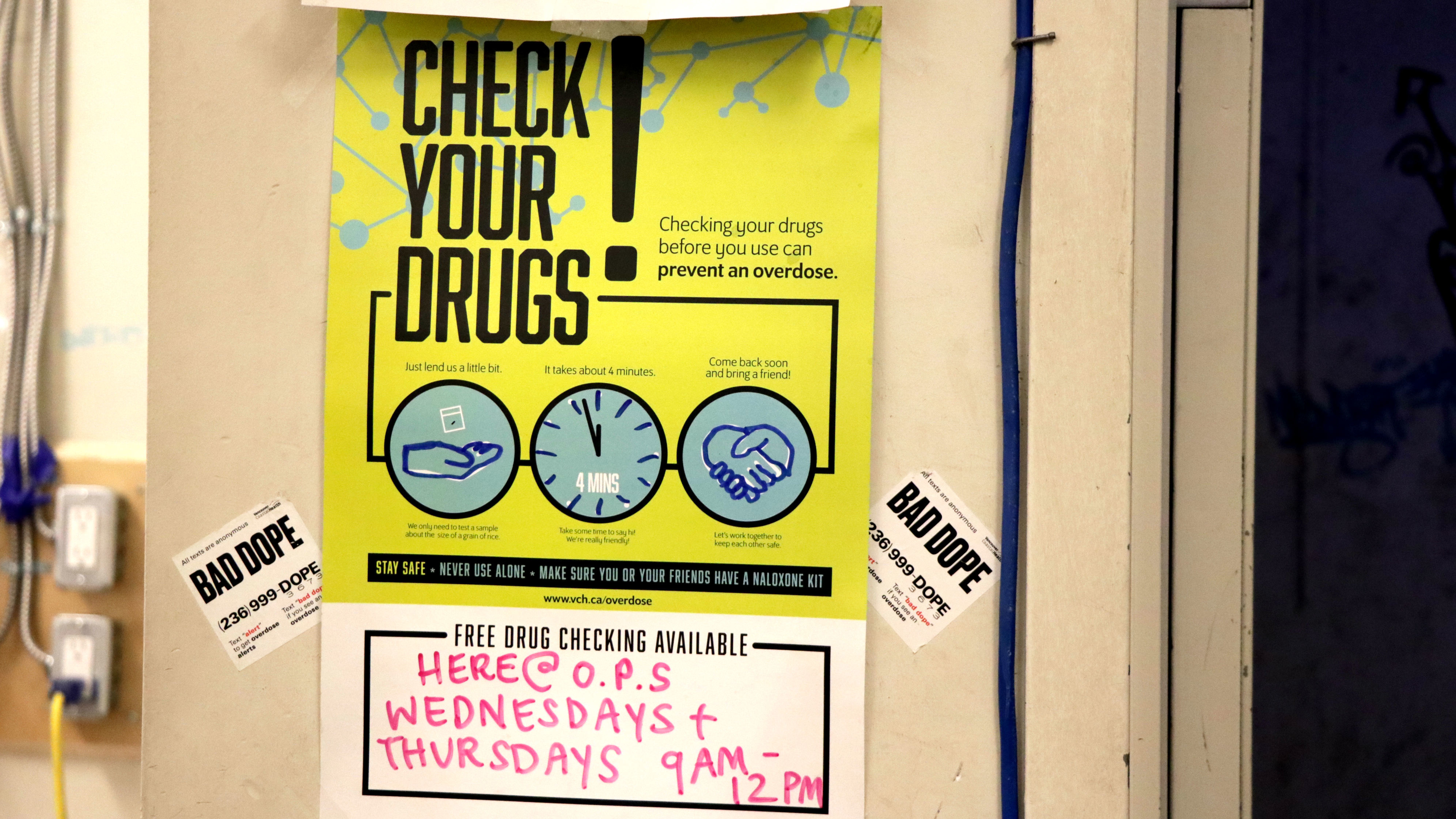

The Overdose Prevention Society is packed with medical equipment, the walls adorned with posters warning people about the latest problems plaguing the drug supply.

Recently, officials realized that many products are now laced with a benzodiazepine-like analogue called etizolam. The deadly combination means users aren’t recovering from overdoses as quickly as they do with the usual antidote.

In the back room, about 10 drug users sit at open cubicles against the wall. Staff standby, Naloxone at the ready in case anyone overdoses — which happens about once a day. At one table in the middle of the room, a man wearing a toque and coat sleeps deeply.

'A problem of drug prohibition'

Mark Haden, an adjunct professor at the UBC School of Population and Public Health, says the province needs to be bold.

Like many on the front lines, Haden wants the province to decriminalize drugs to give people access to a safer drug supply that isn’t laced with powerful, lethal drugs.

“What we need to do is see this problem as a problem of drug prohibition,” Haden said.

Haden also wants the province to put fewer resources into police interventions, which he calls “an inappropriate response to a health care crisis.”

That’s the recommendation Henry hints she will include in her upcoming report.

Drug laws are under federal jurisdiction, but Henry wants the province to divert addiction-related offences from the legal system and instead connect people with health resources.

Henry agrees there have been many positive changes in the province since the public health crisis was declared. But she says there is still a long way to go.

“We have neglected mental health and substance use support in our our health system for a long time. And it takes time to build those up again.”

Many on the front lines agree that the opioid crisis disproportionately affects some of the province’s most vulnerable people — victims of trauma, homeless people, or those with mental illness.

Judy Darcy, the province’s Mental Health and Addictions minister, agrees. Darcy says B.C. has led the country in its response to the overdose crisis, but too many people are still dying.

Darcy says the province has committed to building 2,000 new homes for those who don’t have one. It’s also creating new primary care centres with peer support workers, and providing youth with access to more mental health services.

“The danger is that this will become the new normal and that's why we're committed to continuing to escalate our response,” she said.