October 10, 2018

The blast blew out windows and sent metal fragments flying, ripping through walls and wooden beams inside the P.E.I. courthouse, shattering the stillness of a fall Monday morning.

It was Oct. 10, 1988, just after 6 a.m. The homemade pipe bomb had been hidden in a flower bed at the rear of the building. The force was so powerful it drove some pieces of metal into the judges’ chambers on the second floor.

The bomb went off right under the corner office of now-retired Supreme Court Chief Justice Kenneth MacDonald. When he arrived for work a couple of hours after the blast, he remembers feeling “disbelief that it could happen here.”

MacDonald found “two or three” holes in the floor of his office and one piece of shrapnel lodged in his desk “around where my belly button might be.”

Due to the early hour of the explosion no one was hurt but it did shake up those who worked there.

"I was pretty disturbed. The courthouse was supposed to be kind of a sacred spot,” said Bill Acorn, who was deputy sheriff at the courthouse at the time.

'A pretty safe place … up until then'

“P.E.I. is a pretty safe place. We thought it was up until then,” said Acorn. “We never had bombings on P.E.I. before. That’s just not P.E.I.”

Acorn remembers being assigned to take his German shepherd, Max, to patrol houses of a couple of judges late at night, as a precaution.

Police installed an alarm system in MacDonald’s house. He recalls the phone company mistakenly cutting the wires one day, setting off the alarm, which prompted a team of officers to storm the house — a shock for everyone in the house that day.

Investigators suspected the bomb had been planted by someone with a grudge against the courts, but couldn’t find any solid leads.

Province House targeted

Weeks stretched into months, stretched into years and still no arrests. The bombing eventually slipped to the back of the community’s collective mind.

It took another eight years and a dedicated special task force to link that bombing to three other explosions in Charlottetown and Halifax, and eventually arrest the man responsible.

It was an explosion at P.E.I.'s Province House on April 20, 1995, that put the bomber back in the news.

The device, planted under a wheelchair ramp, went off in the middle of the afternoon during a sitting of the P.E.I. Legislature.

The building was full of politicians, staff, spectators, reporters and tourists. A group of students had walked over the same ramp to enter the historic building just minutes before the blast.

This time the impact was much greater — a man on a park bench suffered a broken ankle and was injured by shrapnel. The force shattered windows, shook the building and the composure of those who had previously considered it a secure place.

Adding to the atmosphere of unease, a day before the explosion at Province House, Timothy McVeigh had bombed the federal building in Oklahoma City, killing 168 people.

Around this same time the Unabomber — Ted Kaczynski — was sending a series of pipe bombs in the Northeastern United States. There had also been a series of unsolved arsons in Charlottetown.

'It left the community in fear'

Due to the close-knit nature of people on P.E.I. police often get tips that help them solve crimes — but not in this case.

“There was a real ‘whodunit’ factor. People didn’t know. No one claimed responsibility initially and it left the community in fear,” recalls Brad MacConnell, now Charlottetown’s deputy police chief.

As the months ticked by, with no arrest, a veil of unease settled in.

“It was a sense of fear that gripped the community at the time,” said MacConnell.

Bomb at propane tank station never went off

Just over a year after the Province House bombing, in June 1996, police got a letter warning of another bomb at a propane tank station on Allen Street in Charlottetown.

The bomb didn’t go off on its own due to a manufacturer’s defect in the timer, said MacConnell, so the bomb squad was called in and used a robot to detonate the device remotely.

“If it had’ve exploded it would’ve had a significant impact on our city,” said MacConnell.

Letters from 'Loki 7'

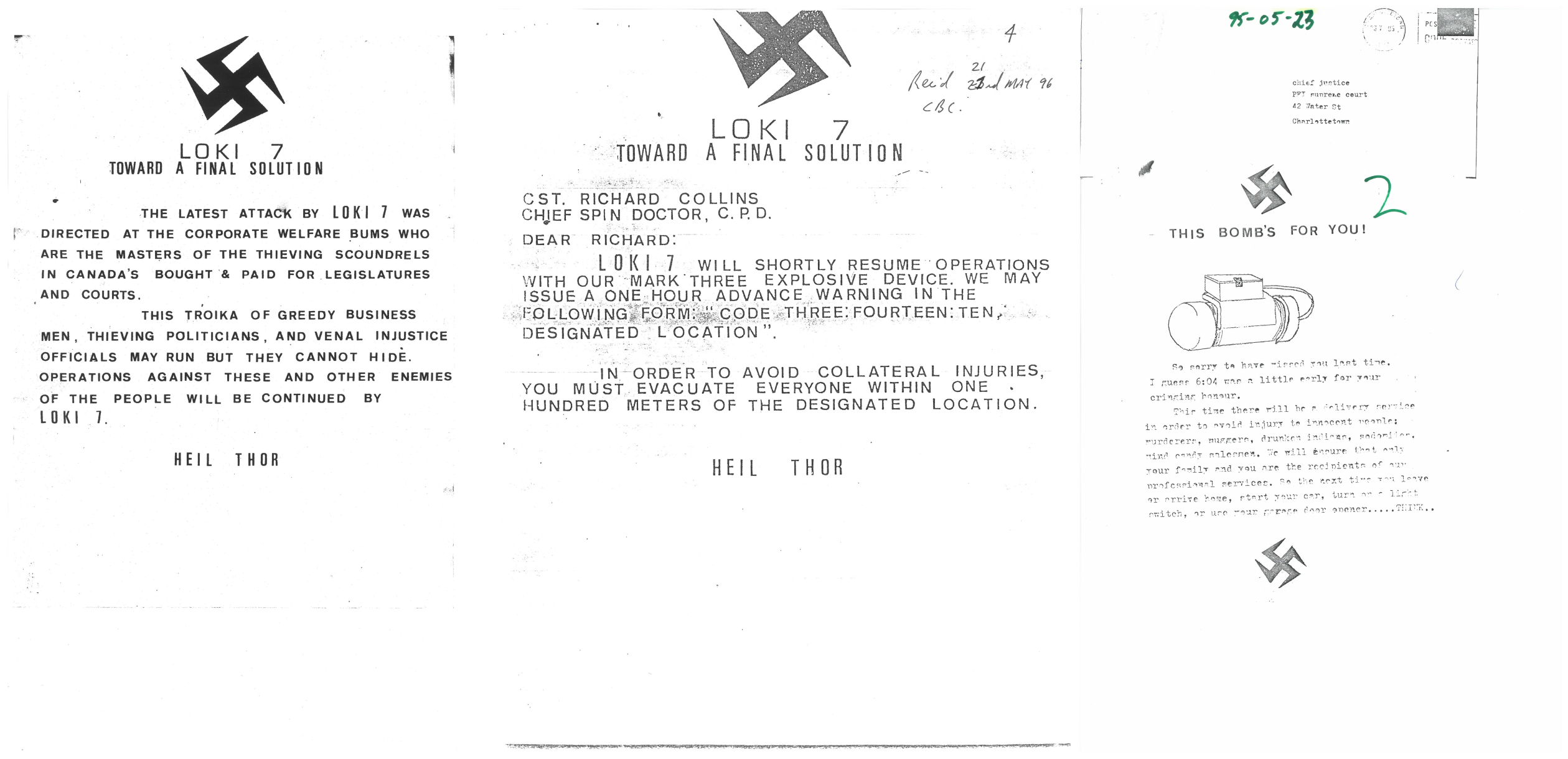

The stakes were raised as the bomber sent letters to police signed “Loki 7.” Loki is a figure in Norse mythology symbolizing destruction and mischief — letters railing against politicians, judges and big business.

Letters also went to the media and officials in the community bearing messages like “This bomb’s for you” and “Next time you open your garage door you better think.”

Loki 7 also took responsibility for a pipe bomb set off in a garbage can at Halifax’s Point Pleasant Park back in July 1994. Police now had a serial bomber on their hands — claiming responsibility for four explosions.

Task force struck

Police assembled a joint task force of RCMP and Charlottetown city police, working full-time on the investigation, supported by resources from other police departments across the country.

MacConnell was brought in for his specialized training in IT obtained in the armed forces. This was a time when the internet was still in its infancy. “I was probably the only officer at the time with those internet skills,” he said.

“We’d experienced bomb threats before but actual bombs going off was totally different,” MacConnell said. “It changed the way we approached those types of incidents.”

The team met in a windowless chipboard-covered room in the basement of a government building — a location kept secret in case the bomber decided to make them a target. There they systematically investigated every possible lead from all four bombings, including the metal fragments, the letters, and tips from the public.

There was “a sense of urgency and pressure to get this solved before the next bomb did go off and cause a loss of life or a huge destruction of property,” said MacConnell.

The task force put together a list of 10 suspects. One of them was retired high school chemistry teacher Roger Bell.

Piecing it together

He was on the list based on a tip from a man who knew Bell and had “deep concerns” he was responsible. He’d also been flagged by Canadian Border Services a few years earlier for buying a book about explosives.

Gradually, the pieces of the puzzle came together.

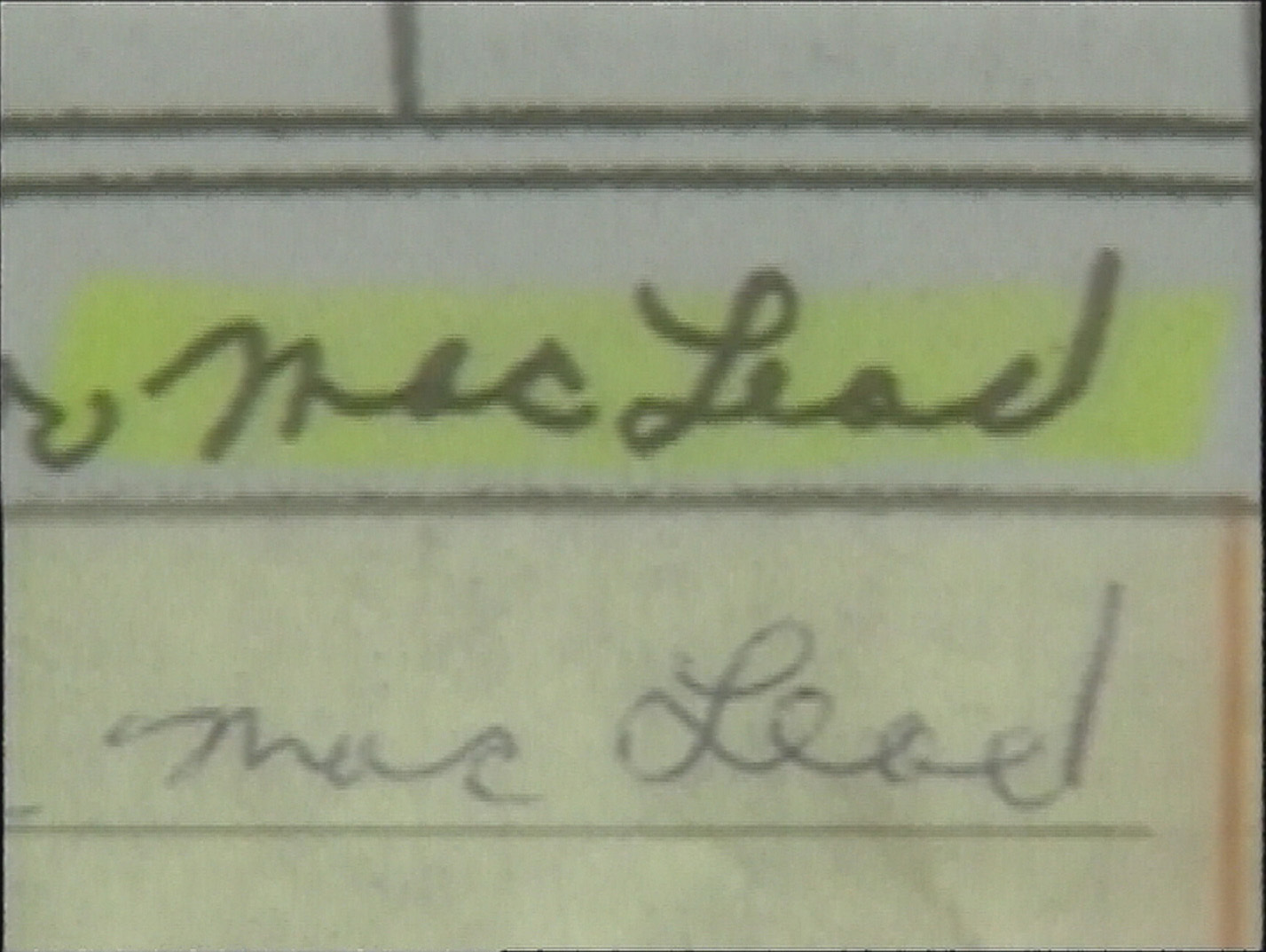

The size of the pipe used in the bombings led investigators to a plumbing supply store in Moncton, and a handwritten cash receipt.

When they checked Bell’s handwriting from school records against the receipt, they got a match, confirmed by a police handwriting expert.

They checked Bell’s garbage for clues. There they discovered Bell consistently played the same numbers on his lottery tickets.

When they checked with the lottery commission they found the tickets were consistently bought at the same store near Bell’s apartment in Charlottetown except for two occasions: they were played in Halifax, at the time of the bombing there; and in Moncton, N.B., at the same time the pipe was purchased from the plumbing supply store.

As leads were further pursued, more and more evidence came together, all pointing at Bell.

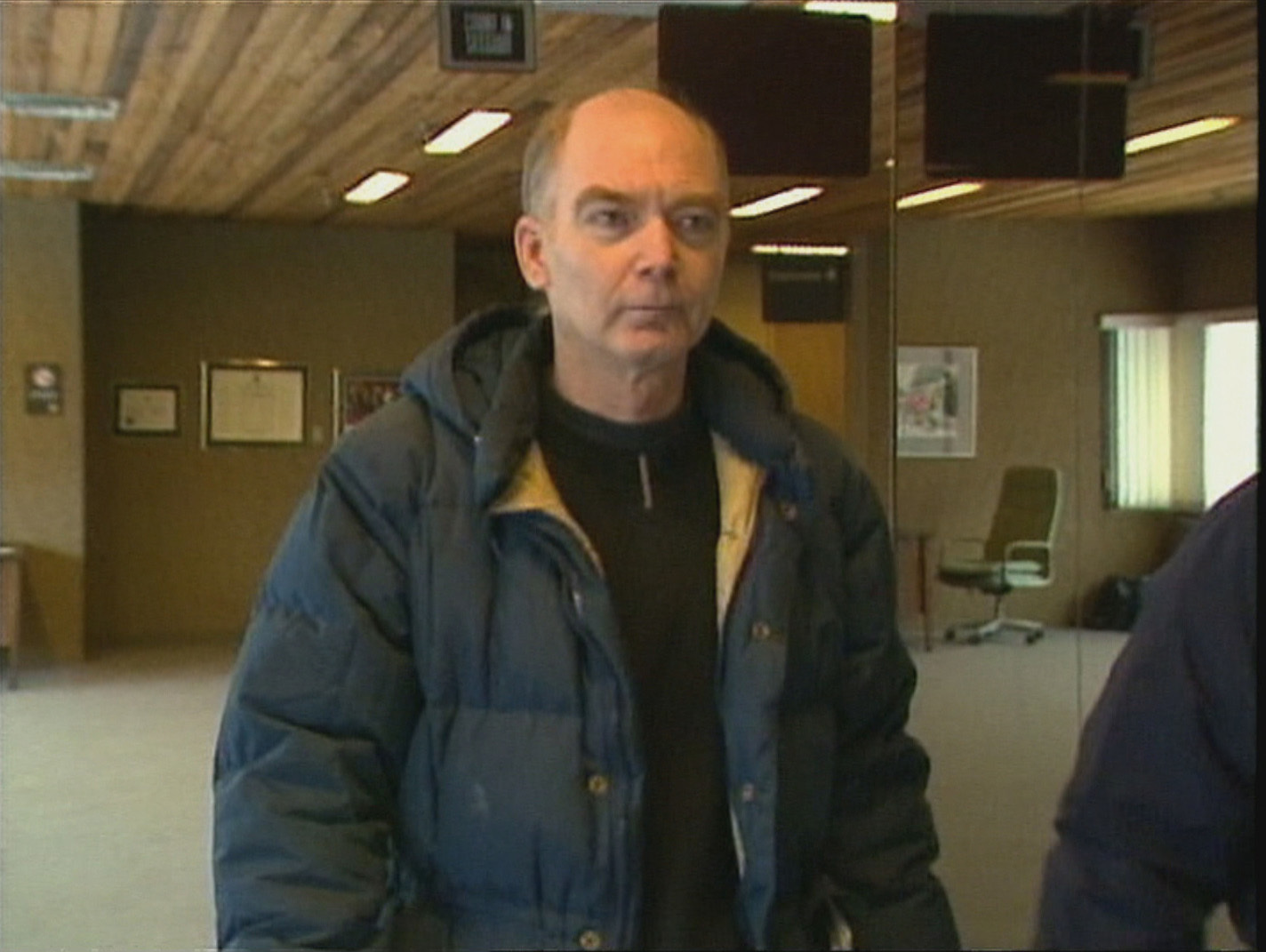

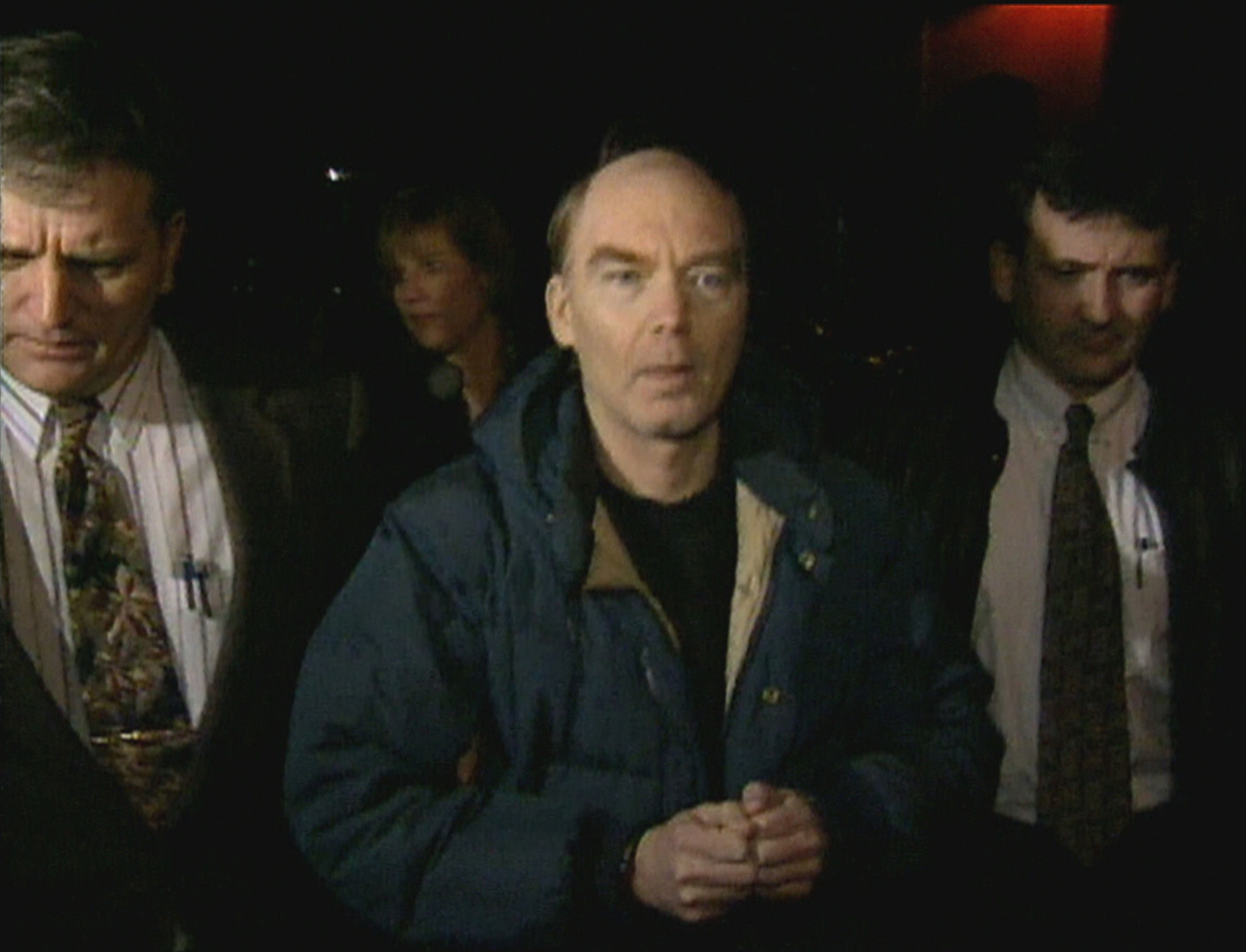

When the task force was set up initially it was thought it might take several years to track down the bomber, however within six months, the task force decided there was enough evidence to arrest Bell. They took him by surprise, entering his apartment around 7:30 a.m. on Dec. 16, 1996.

Sentenced to 9 years in prison

Bell ended up pleading guilty to all four bombings, and was sentenced in June, 1997, to nine years in prison.

In 2002 he told a parole board hearing that his run-ins with the courts, government and big business had left him feeling mistreated by society.

"I think my mission was simply revenge at society," he told the board.

Bell was released from Springhill Penitentiary in 2003 to a halfway house in Halifax. In 2004 at the age of 60, he was given permission to leave institutional supervision and move into his own place.

'A bit of wake up call'

In the two decades since Bell’s arrest, the world has witnessed the 9/11 plane crashes in New York, and numerous terrorist attacks around the world. Changes in security have grown exponentially.

At the P.E.I. courthouse, sheriffs screen visitors to the building, who must also walk through metal detectors. And many areas of the building have restricted access.

Acorn is still working at the courthouse — as a part-time commissionaire.

“It’s like day and night," said Acorn, comparing security now to 1988. "We’ve got security cameras all over the place. You can see someone coming a block away.... It’s a big, big difference.”

“Loki 7 was the catalyst to getting security cameras around the legislature and courthouse. That has evolved today to our E-Watch around the city,” said MacConnell, referring to the 70 surveillance cameras across Charlottetown.

Today, he said bomb threats are traced immediately, and investigators work quickly to involve other policing agencies when they investigate serious incidents that pose threats — whether those agencies are in other parts of P.E.I., across the country or globally.

Although P.E.I. still maintains a relatively low crime rate the bombings on P.E.I. “did change some of the innocence of our population and the fact that we’re not immune to these types of things,” said MacConnell. “1988 was a bit of wake up call for Prince Edward Island.”

Nov. 25, 1997 report on the P.E.I. Bomber