For Mill Woods homeowner Lorna Dyck, the history of Papaschase First Nation is all around her.

Eighty pages outlining her family tree, dating back to the 1700s, sit on her living room table, along with a pamphlet from the First Nation that lists the names of some of the earliest band members.

Her ancestor, Catherine L’Hirondelle, a medicine woman, is the earliest example of her ties to the First Nation that used to live on the land that is now Mill Woods.

“I am proud to be from Papaschase and proud to be Métis,” Dyck said.

She has spent decades searching for family connections to the band, a role she has taken over from her parents, who were both Papaschase descendants.

Like many other band members, that family history can be difficult to track.

The Mill Woods area was once part of the land occupied by the Papaschase First Nation, after they signed an adhesion to Treaty 6 in 1877.

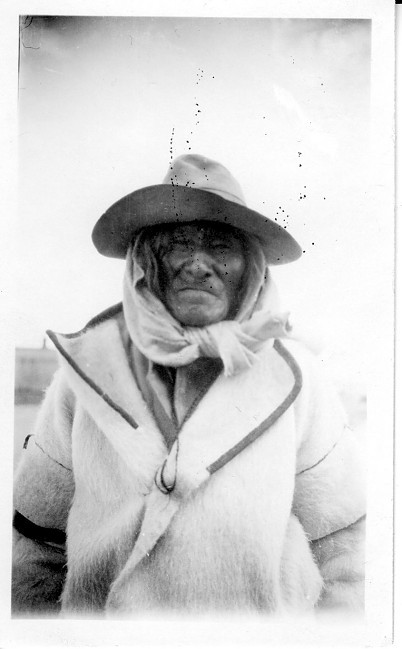

Many band members scattered after their land was taken away a decade later, according to Chief Calvin Bruneau. But some remained in Edmonton, including Dyck, who has lived in Mill Woods for 42 years.

She said it was important for her to stay in the area her ancestors once called home. Stories passed down to her recall a time when her great-grandparents picked berries in what is now Mill Woods, a memory she has cherished over the years.

“I have really good feelings [about the area]. If I’m feeling down, I can go for a walk or take a drive and I can feel my ancestors around me,” she said.

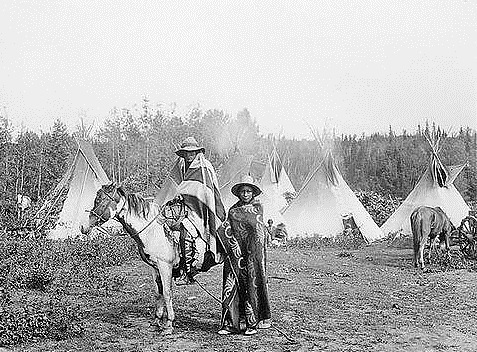

The Papaschase people moved in the 1850s from the Lesser Slave Lake area to the area around what was then Fort Edmonton, to hunt and trade with the Hudson's Bay Company.

Chief Papaschase signed an adhesion to Treaty 6 at Fort Edmonton in 1877. A year later, surveyors with the federal government were sent out to find reserve land for the band, according to the Papaschase First Nation history.

Bruneau said the treaty outlined that one square mile of land would be designated for every family of five that was part of the Papaschase band.

“The treaty was a way to help us survive, but the government was breaking the treaty,” Bruneau said.

The band population at that time was 249 people, he said, but the government omitted certain members and designated only 40 square miles of reserve land for the band.

Papaschase band were eventually relocated to what is now southeast Edmonton.

Bruneau said several years later, many band members were starving, some dying from lack of food.

After the Riel Rebellion in 1885, the government offered people, including Papaschase band members, Métis scrip, which gave members the choice to take either a parcel of land or money, said Bruneau.

Twelve Papaschase members took Métis scrip. By taking the scrip, they then lost their treaty status, he said.

Bruneau said his ancestors were forced to take the money so they could survive.

“In order to feed their families, they took the Métis scrip,” said the chief.

In 1886, 102 members had taken scrip, the chief said.

A year later, some of the Papaschase band were persuaded to move to Enoch Cree Nation or to other reserves, he said.

Indian Affairs officials advocated for the removal of the remaining Papaschase people from their land. Three band members agreed to a land surrender, and the south-Edmonton plot of land was later sold to third parties, according to the Papaschase First Nation history.

“Put all of these factors together, that’s how the band was broken up and dispersed,” Bruneau said.

Educating the next generation

With band members scattered, the Papaschase band was left without land, according to Bruneau.

The stories of the Papaschase band were passed down through the generations, he said, keeping memories of their ancestors alive.

Dwayne Donald, a descendent of the Papaschase Cree and an associate professor of education at the University of Alberta, has been hosting river walks in Edmonton’s river valley since 2006. It was an exercise he started with his students when he decided to take his lectures into a natural environment and teach them about the land and local history.

He now guides the walks for the general public, by request.

He often speaks about Papaschase history and tells people about the separation of wahkohtowin, the Cree word for kinship, which represents both human kinship and kinship with the environment.

“Part of the tragedy of the Papaschase, apart from what happened to them materially and the violation of the treaty agreement, was also the very violent separation of wahkohtowin, kinship sensibility," he said. People who have come to live here have never had the chance to learn about it. That is something I really try to attend to, and try to help people understand on that walk."

His passion for guiding people also extends to his classes at the faculty of education at the U of A.

He is teaching two courses this fall semester, including one called “Aboriginal Curriculum Perspectives.”

He passes along his knowledge to the next generation of teachers by allowing students to express their own thinking. Instead of a final exam, he gets his students to do a Winter Count, a traditional practice of some Indigenous peoples.

“The traditional practice was to get a buffalo hide," he said. "It was someone’s job in the community to identify significant events that happened in the previous trip around the sun. They might have a number of things they may want to remember, so once they reach consensus on one or two things, the job of the Winter Count maker was to create a symbol that represented that event or that story. These symbols would be painted on a buffalo hide in a recognizable pattern. Some could have 70 to 80 years of memory."

With many symbols on the hide, the Winter Count would work as a mnemonic device, he said.

His students are asked to make their own symbol for every week of the class.

Over the years, students have sculpted, created melodies or drawn symbols they felt represented the class.

“That’s the kind of thing I’m interested in," he said. "That honours that tradition, we just have to update it.

“For me, it honours the wisdom. People have found it so meaningful.”

'We need to rebuild the band'

Bruneau said connecting with Papaschase descendents remains one of the most critical steps today.

Many, like Dyck, are tracing their family heritage and learning about their Papaschase ancestors.

But the chief said the most critical next step for the Papaschase First Nation is to be offically recognized by the federal government. They are currently not listed on the federal government’s website as an official First Nation. Bruneau said some of their approximately 1,000 “probationary” band members cannot get Indian status until they become an official First Nation.

The Papaschase band filed a claim in 2001, but it was "tossed out of court in 2008 because of technicalities," said Bruneau. He said one of the reasons is because they "were not a recognized band."

Now the process to become an official First Nation is back in motion.

“Any claim going forward would have to include Enoch,” he said of Enoch Cree Nation.

Discussions are underway with Enoch, he said, and he’s optimistic a joint claim will move forward to the federal government.

Enoch Cree Nation was not able to be reached prior to publication.

Bruneau said he wants all levels of government to acknowledge what happened to the Papaschase band. With government recognition and official First Nation status, he hopes Papaschase will eventually have their own urban reserve, businesses and schools.

The chief said creating more awareness about what happened to their band is key. Papaschase leaders recently consulted with city and contract officials involved with the construction of the Valley Line LRT that will extend to Mill Woods.

He said it's a step in the right direction in establishing Papaschase as an official First Nation and shows how now is the time to move forward with a claim.

“We need to rebuild the band, we need to rebuild our nation. If the government didn’t do what they did, we’d still be on the south side,” said the chief.

“We’d have land, houses, we’d have administration, businesses, schools, everything that is built on there now. Now we have to reassert ourselves, come back into Edmonton and say ‘Well, we’re back.’ ”