September 30, 2021

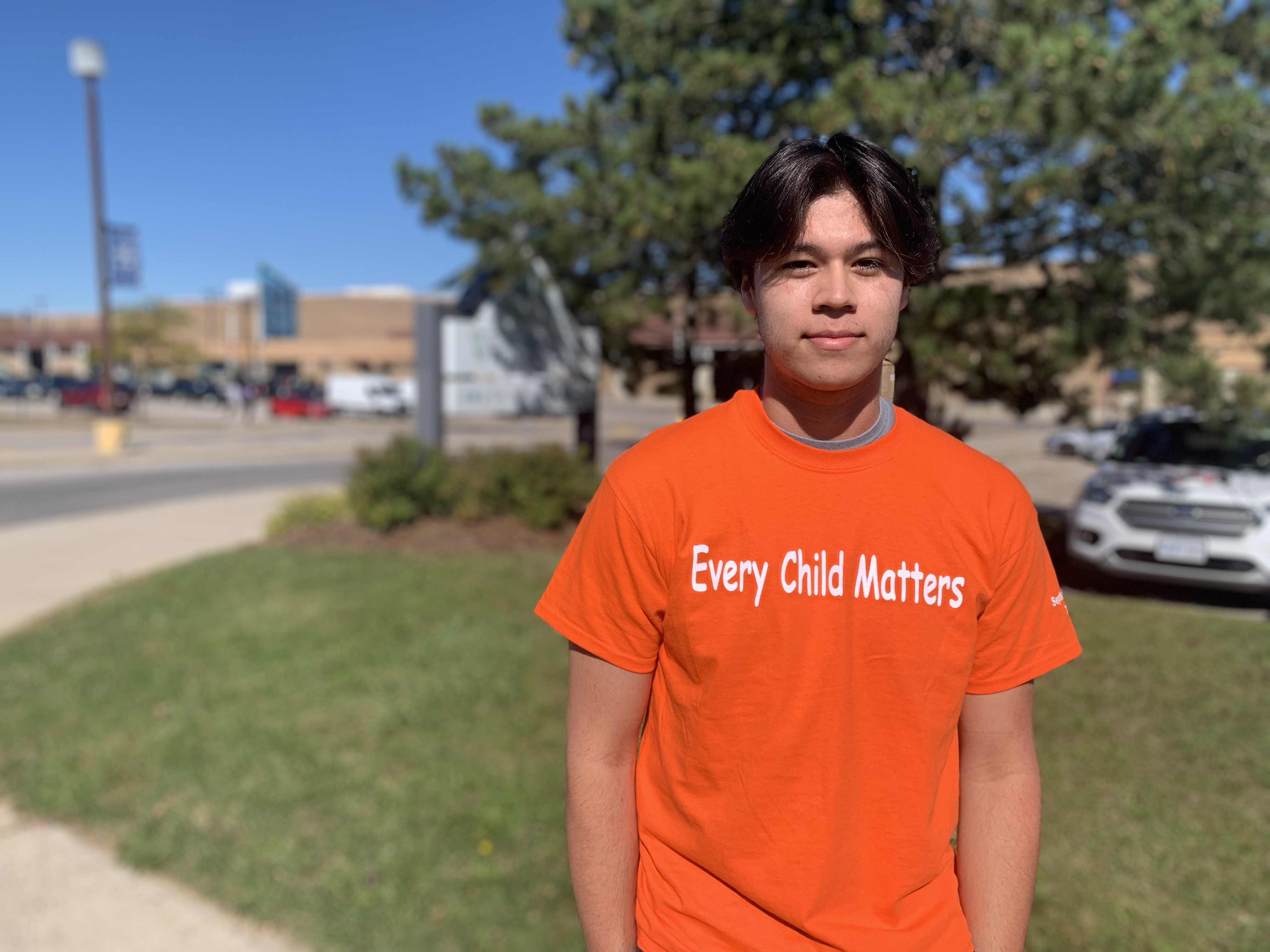

Canada’s first National Day for Truth and Reconciliation is a time to reflect on the country’s “dark” past, including the horrors experienced by Indigenous people at residential schools, but also an opportunity to move forward to share successes and culture, says Dillon Moses Strasser Einish, a high school student in London, Ont., who is from the Naskapi Nation of Kawawachikamach in northern Quebec.

“It’s a day to acknowledge our dark history and what Canada has done, instead of brushing it aside that way we’ve done for so long, for years and years and decades,” Dillon says.

“It’s nice to know that we’re finally being heard and that our time is coming up, that we’re emerging from this dark history that we’ve had.”

On Sept. 30, kids in schools across the country will wear orange shirts, a visible reminder of the legacy of Canada’s residential schools, which tore children from their families in an attempt to erase Indigenous culture, tradition and language.

Dillon loves musical theatre and singing. He’s also part of the Grand Confederacy Council, which brings together Indigenous students from nine high schools in the London District Catholic School Board, a chance for the teens to learn from and about each other.

“When I first moved here from northern Quebec, I found it really ironic that an Indigenous kid was at a Catholic school, but I can teach people here and educate them,” says Dillon, who moved to the southwestern Ontario city after his dad died.

It is his father’s Indigeneity that inspires him to open up to others about his heritage.

“My dad was the one who wanted to know all about the culture and bring it to light. He was into drumming, smudging, sweat lodges,” Dillon says.

“Today is such an important day to remember that kids were forcibly taken from their homes and never made it back. I just hope that in the society we live in now, we are all able to come together for each other in times of need.”

Zephyr Collar knows his great-grandmother and grandfather went to residential schools.

“When [my great-grandmother] went in, she could only speak the Oneida language, but when she got out she would only speak English to us,” Zephyr says.

Now, the nine-year-old is learning Oneida alongside his mom, who also doesn’t have the language of her ancestors.

“It’s good to remember every year, on Orange Shirt Day or any day, what happened.” Orange Shirt Day is now called the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation.

Zephyr participates in ceremonies and smudging, and has grown his hair long, a symbol of strength and wisdom.

The Grade 4 student is into hockey and lacrosse. He’s also taking guitar lessons. His eyes light up when he talks about the culture that elders share with him.

“It’s not about the colour orange. It’s about residential schools. Sometimes, back in the day before residential schools happened, they did the quiver dance. A quiver is something you wear on your back to hold arrows, and before they went to hunt food, they would stack all the quivers and they would dance around it and chant. No drums, no rattles, just a chant. It would be a good luck for catching some food.”

Catherine Masutti didn’t know about her Indigenous heritage until a few years ago, when her mom started exploring her own ancestry after the death of her own mother.

“There was alcoholism in my family that caused us to distance ourselves from my grandfather, but now we’re working on rebuilding that and it’s really good to know what’s been missing. It makes me feel whole.”

The 17-year-old has discovered her father’s family is Algonquin and Métis, from the Ottawa area.

“For me, this day is really important because it gives us the opportunity to discuss the effects of residential school and the families that went, and the legacy that they left behind,” she says, acknowledging her separation from her culture is part of that legacy.

“It’s rough because of all the knowledge I’ve lost and my mother has lost as well, with that culture that we didn’t know about.”

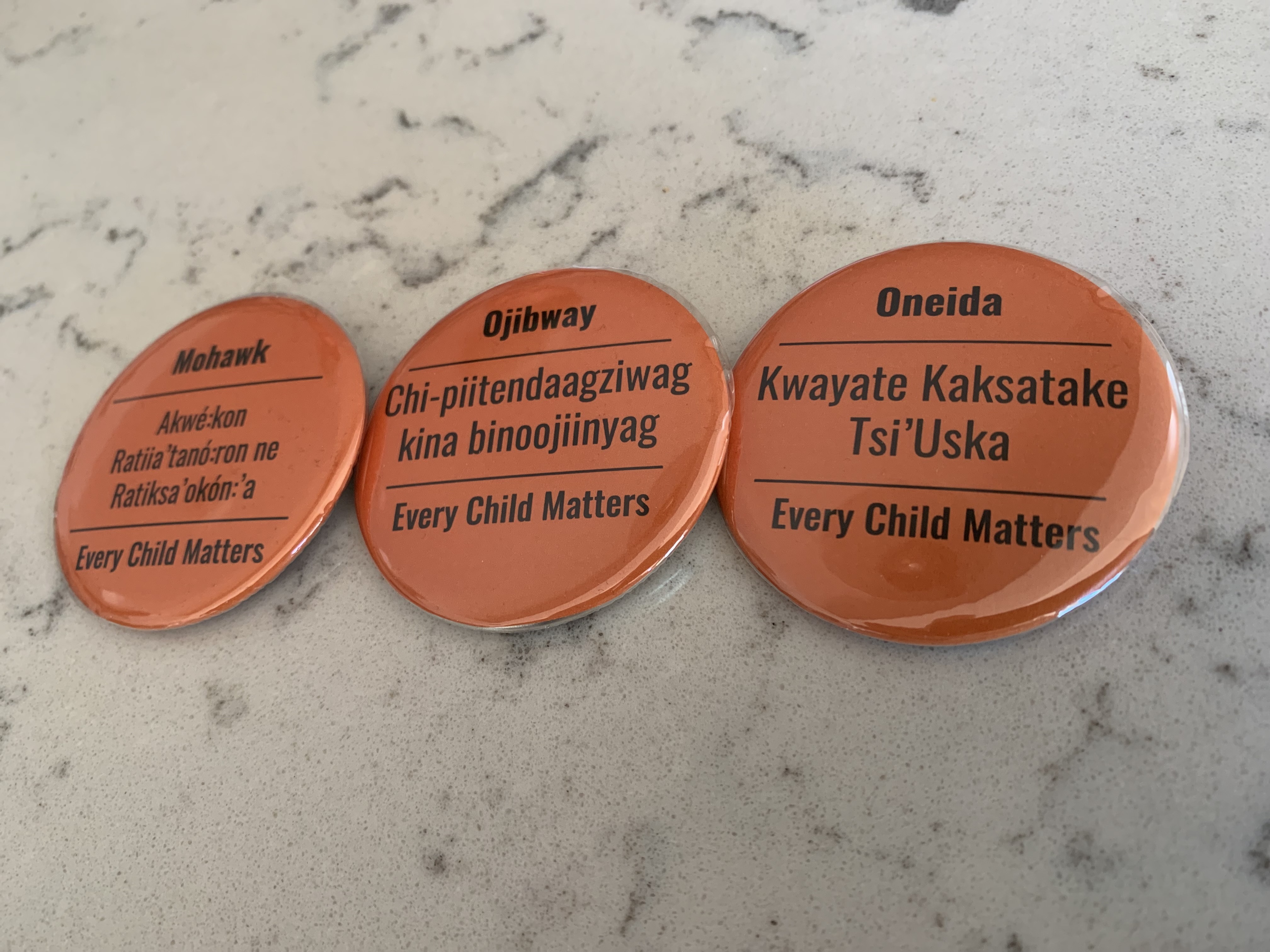

Catherine is part of a group of students who have designed buttons and keychains, created by the technology students, with proceeds going to Atlohsa, an organization that helps strengthen communities through Indigenous programs and services.

Eventually, she wants to go into health sciences, and use Indigenous and other cultural traditions to heal people.

For Emmerson Deagle, news of unmarked graves on the lands of residential schools hit close to home. His family is from the Cowessess First Nation in Saskatchewan, and his grandmother’s siblings attended the Marieval Indian Residential School, where 751 unmarked graves have been identified.

“Today is a day to understand what happened for those many years to those students, and to understand what the Canadian government did to us,” says Emmerson, 17.

But he also wants the school curriculum to move past the negative aspects of Indigenous history.

“We spent two weeks, just two weeks, talking about Indigenous history, and all we did was residential schools,” Emmerson says. “We didn’t learn anything about culture, about food, the colours, the land, the language, songs, hunting the land, none of that. We need to change that.”

That way, Canadians can get a more whole picture of Indigenous life and people.

“Residential school is a wound that’s never really going to heal. It will always leave a scar on those people that attended or had families that attended,” he says.

Now, Emmerson is part of a school community in London that embraces his Indigenous heritage.

“I’ve done teachings about medicine and aspects of cleansing, and I absolutely love it. I love teaching people about my culture as I’m learning about it, too. I started to learn about my culture and I was taken aback by how beautiful it is, and now I want to share those roots with everyone."

It’s the strength of the Indigenous people that high school student Niigonii White-Eye hopes people remember long after the Day of Truth and Reconciliation is over.

“This day is a big deal for me because it’s proof that assimilation was not successful and our people are so strong, and there are generations of us to come,” says Niigonii, 17. He’s a student trustee with the Thames Valley District School Board, a role he sees as a chance to be a voice for his peers at the decision-making table.

“I want people to really take the time to appreciate and commemorate the survivors of residential schools and listen to their stories because we can learn so much from them,” he says.

“I want people to know what we’ve been through and how strong and resilient we are.”