August 3, 2020

They're back. And they're hungry.

"The females are incredibly good moms," said researcher Erin Foster, after spotting a sea otter feeding her pup in the ocean waters off northern Vancouver Island.

Foster was surprised to see the size of the meal the mom had secured. It was a large geoduck (pronounced gooey-duck) clam, which Foster equated to a person eating an entire loaf of bread in one sitting.

"She has a huge pile of meat on her chest, she's tossed the shell overboard and the pup keeps jumping on top of her, biting pieces off," Foster said excitedly.

The fact that sea otters are living in this bay at all is an incredible tale of recovery for a species once hunted into oblivion for its lush fur. Now numbering in the thousands, their ferocious appetite is dramatically altering large parts of the West Coast ecosystem.

Despite its cute and fuzzy appearance, the sea otter is a top predator. Without them, the underwater environment changes dramatically. When otters were hunted out of existence in B.C., the population of one of their favourite foods — sea urchins — exploded.

Those urchins went on to eat vast forests of kelp that once blanketed much of the B.C. coastline. Stretching up to 36 metres from its root-like holdfast on the rocky seabed, kelp is a vital habitat for a diverse range of species.

Less kelp equals less diversity.

With the return and resurgence of sea otters, the ecosystem has been changing yet again. It all has far-reaching consequences for multimillion-dollar commercial fisheries as well as people who had been harvesting shellfish for food along the coast for generations.

Foster watched the feeding session from a small, rocky islet, observing through a powerful spotting scope that gave her a close-up of the action.

Documenting what otters eat helps researchers assess the species' impact, and the geoduck was on full display as the mother used her chest as a fur-covered kitchen table to feed her pup the morning's meal.

"What's really cool is when we have the time to watch them there for a few months and just watching how quickly they change the ecosystem. It's incredible," said Foster, who has been charting the steady expansion of the otters' range along with other researchers.

As a murder is to crows, a raft is to sea otters. They like to gather in large groups, floating close together over kelp beds near the shoreline. On this July morning, Foster counted 59 in one small bay alone, a mix of males, pups and mothers.

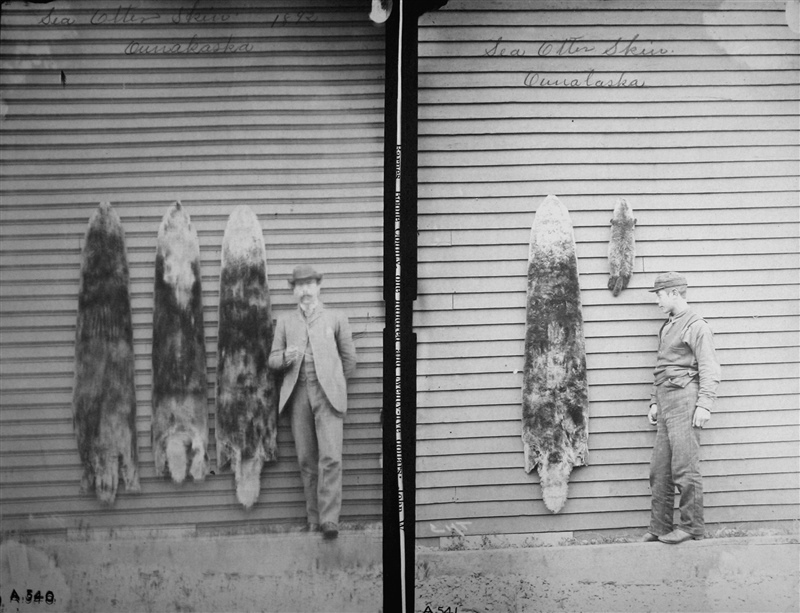

In appearance, they're one of nature's warmest and fuzziest of critters, with their broad whiskers, curious gaze and playful demeanour. Their glossy fur coat is spectacular — so much so, it led to the otter’s downfall in the region. It is incredibly thick and warm, trapping air to form an insulating layer against the cold Pacific water. Unlike other ocean mammals, they have no insulating layer of blubber.

The history of the otter is unique in that its disappearance along Canada's West Coast coincided with rapid population growth of non-Indigenous people.

Before the commercial maritime fur hunt began in B.C. in the late 1700s, up to 300,000 sea otters were believed to be living throughout the north Pacific Ocean, with a range from northern Japan and the Aleutian Islands all the way along the West Coast of North America.

The otter's unique, dense fur was considered high fashion in China, motivating foreign traders to flock to B.C.’s Nootka Sound to fill their ships with tens of thousands of pelts, which they sold for an exorbitant profit overseas.

Within about 100 years, the fur trade had extinguished itself because there were so few of the animals left along the West Coast. By the early 1900s, sea otters had been hunted to the brink of extinction right across the North Pacific, with only a few pockets surviving in inhospitable, remote areas such as the Aleutian Islands.

In 1929, the very last sea otter known to inhabit British Columbia's waters was shot dead off the coast of Vancouver Island.

Capture and return to B.C.

Since the otter had been largely wiped out for so many years, there was little knowledge about the animal's role in the coast's food web.

Historically, Indigenous communities had long co-existed with sea otters, but they, too, adapted as otters disappeared and other wildlife moved in. The sea otter was something preserved in Indigenous culture and language, but not in the everyday experience of people living on the coast.

In the late 1960s, Canadian biologists began planning to return sea otters to British Columbia. Biologists in Alaska had already started a capture and relocation program, transplanting otters from areas where they were plentiful to locations where they had been wiped out.

Helped by their U.S. counterparts, Canadian biologists captured dozens of sea otters in Alaskan waters in the summer of 1969. The plan was to relocate the animals south to the B.C. coast, something that had never been done before.

This documentary followed the three-year project that released 89 otters into B.C.'s Checleset Bay. (CBC Archives)

After capture, the otters were transported by boat, helicopter and aircraft from Alaska to Vancouver Island.

It didn't go well.

Forty per cent of the captured animals died on the long and complicated journey to B.C. due to stress and overheating.

In 1970, scientists tried a different approach, sending a Canadian Coast Guard vessel to a section of the Alaskan coast where otters were abundant. Special saltwater pools were built on deck to transport a large number of otters at once.

There were some fatalities, but in the end, 89 sea otters were successfully reintroduced to Checleset Bay, near the remote northwest tip of Vancouver Island.

Provincial officials were confident the otters would survive back in their native waters.

In a 1971 interview with the CBC, Ian Smith, a B.C. government wildlife biologist who was part of the expedition, said the animals quickly divided into small groups upon their release.

"The big question is not whether they'll just survive, but whether they'll breed," said Smith.

"And this means finding mates in the ocean, and it's a big ocean out there."

Since their reintroduction 50 years ago, the otters have thrived on their own in B.C., growing from a population of 89 in 1972 to about 8,000 in the most recent federal wildlife survey in 2017.

From their initial release point in Checleset Bay, their range has spread hundreds of kilometres around Vancouver Island, north to B.C.'s Central Coast and, most recently, Haida Gwaii.

Some people mistake the sea otters for their smaller relative, the river otter, which, despite its name, is also frequently seen in the ocean. But sea otters are much larger, with males measuring up to 1.5 metres long and weighing up to 46 kilograms.

What started as an experiment has become a significant conservation success story.

"Sea otters were introduced and then just left to be, and they did what they did," said Jane Watson, an adjunct professor of marine ecology at Vancouver Island University who has monitored the impact of B.C.'s otters more extensively than anyone over the past 30 years.

"When sea otters were reintroduced, no one knew that they were going to change ecosystems," Watson told CBC News on a recent visit to Nanaimo, B.C.

"The first paper on sea otters came out in 1974. Nobody knew," she said, referring to the lack of scientific study at the time on otters and the role they play in the food web.

Indigenous impact

One of the first Indigenous communities to experience the impact of the otters' resurgence was Kyuquot, on the west coast of Vancouver Island. Prior to the otters' return, locals gathered clams, urchins and other shellfish in nearby waters.

A recent Simon Fraser University study featured interviews with community members to document the oral history of the otters' impact as their numbers increased.

In the 1970s and '80s, Kyuquot elder Hilda Hanson, 98, saw otters decimate the supply of clams, urchins and other sources of food in her community's traditional territory.

"We had big clam beaches.... The best clam beach that ever was," she said, describing a productive clam bed near the village that people had relied on for decades to provide food.

"All what we ate was taken away by kwaka [sea otters]."

Janice John-Smith, hereditary chief of the Kyuquot/Cheklesaht First Nation, told the researchers that as the wild shellfish grew harder to find, people shifted to less nutritious store-bought foods.

"Today, a lot of people suffer from many sicknesses, and we get so used to eating bought meat and everything," she said.

She also decried the fact Ottawa and B.C. made the decision to reintroduce the otters without consulting her community.

Three elders in Kyuquot, Hilda Hanson, Daisy Hanson and Peter Hanson, describe how access to some of their traditional foods was upended following the release of sea otters into local waters. (Courtesy: coastalvoices.net)

Commercial impact

The commercial shellfish industry also has concerns about the growing sea otter population.

The furry animals are eating their profits.

Dungeness crab, sea urchins, sea cucumbers, clams and other wild shellfish are a $100-million-a-year business in B.C.

"It's a huge challenge, a huge impact," said Grant Dovey, head of the Underwater Harvesters Association, which represents the geoduck fishery.

He said quotas have been cut on the west side of Vancouver Island by about 40 per cent because of the voracious otters.

"Once the otters are established, for the most part, most of the beds aren't commercially viable anymore. So it's a big hit."

He is convinced that further quota reductions are coming as the sea otters continue to expand into areas now used for commercial clam harvesting.

Trade-offs

Commercial shellfish harvesters and some Indigenous groups have discussed the possibility of a limited hunt to help manage otter populations in areas where their behaviour conflicts with human activity.

"I think the way people did it in the past is they kept them away from where we were close by," said Kyuquot Hereditary Chief Peter Hanson.

"They hunted them there and kept them off the sea urchin beds so that they didn't take everything. It could be done again."

Archeologists suggest there was a long history of hunting sea otters, both for their pelts and to keep them from competing with humans for food.

Despite some negative impacts on humans, the sea otters' return to B.C. is a potentially significant boon to both the underwater ecosystem and the economy.

For instance, in places where otters have moved in, kelp forests are being regenerated after having disappeared along with the otters. What were once sea urchin barrens are now lush kelp beds, providing new habitat for a wide range of creatures, including rockfish and salmon.

This summer, researchers at the University of British Columbia released a study suggesting the otters are a net benefit to the B.C. economy, despite their negative impact on some lucrative shellfish fisheries. The paper, published in the journal Science, attempted to weigh the environmental benefits of the otters' return with the economic and social impacts they've presented for fishermen and Indigenous communities.

The researchers estimated the total loss to fisheries caused by otters to be around $7 million per year, although they acknowledge a wide margin of error. They also said the loss of shellfish is felt more deeply by people in coastal communities who don't have access to boats or fishing licences.

But the study found underwater kelp forests have grown twentyfold since otters repopulated the B.C. coast. The researchers said the kelp comeback has caused stocks of lingcod to triple, and the overall amount of sea life has increased by 37 per cent, which has helped increase revenue for some commercial fisheries.

There's also a benefit in the fight against climate change. The growing kelp forests store carbon by locking it into the algae's tissues and transporting it deep into the ocean. The study says this carbon sequestration is worth about $2 million at current carbon prices, which are traded on international markets.

"It turns ecological interactions into dollar signs, which, as an ecologist, I struggle with," said Jane Watson, who co-authored the study.

"But it just suggests that putting an animal that belongs in an ecosystem back in an ecosystem allows it to function the way it's supposed to function, and that probably has more value to human beings."

Two of B.C.'s most experienced sea otter researchers, Linda Nichol and Jane Watson, say the animals' return is 'flipping ecosystems' in complex, new ways. (CBC)

Otters return to Haida Gwaii

Because otters have been spreading slowly up the coast, some communities have had much longer to prepare for their return.

Until recently, there were few confirmed sightings near Haida Gwaii. The archipelago is separated from the rest of the coast by large expanses of open ocean that make it difficult for breeding colonies to cross and get established. But last year, 13 otters were confirmed in one region of Haida Gwaii. The exact area is not being disclosed in order to protect the small population.

Cindy Boyko, a member of the Haida Nation and co-chair of the Gwaii Haanas Archipelago Management Board, sent a statement to CBC about the otters' historical role and return.

"The long absence of kuu [sea otters] reminds us of the importance of gina 'waadluxan gud ad kwaagid, or everything depends on everything else."

Boyko said she believes it's important to restore the natural balance, writing, "The return of sea otter represents an opportunity for renewal."

An ongoing study by Parks Canada and academic researchers working in the waters off Haida Gwaii is trying to replicate what will happen as the otters return in greater numbers.

The experiment, which started in 2017, is attempting to restore a kelp forest by having scuba divers remove sea urchins by hand, replicating the impact of otters as they feed on the urchins. Once the kelp grows back, the hope is abalone, rockfish, herring and salmon will thrive with increased habitat.

Prior to beginning the underwater study, biologists had declared the urchins "hyperabundant" in the absence of their otter predators.

Flipping the ecosystem

Now that more is known about the returning otters' impact, biologists and other advocates believe it will be widely seen in a positive light overall, much like the return of wolves to Yellowstone National Park in the U.S., where the predators helped rebalance the complex ecosystem.

Mike Willie, a hereditary chief from the coastal Kwikwasut'inuxw Nation, says he has heard some negative talk about the otters, but he sees them as a long-term benefit for the region.

He spoke to the CBC on board his boat in the waters off northern Vancouver Island, on the way to see his latest venture at an old village site on Hope Island, called Place of the Otter.

It's an idyllic spot, with a sheltered bay wrapping around a gravel beach.

Willie's company, Coastal Rainforest Safaris, was set to help revive the site as a high-end camping, or glamping, outpost this year. Large tents were to be erected on top of a new boardwalk, with tourists paying $1,000 a night to experience the region's wilderness.

The COVID-19 pandemic has delayed those plans, but it hasn't dampened Willie's enthusiasm.

"I'm excited about it.… Sea otter viewing is giving First Nations a chance out here to take part in the mainstream economy."

He said with other local industries such as logging and fishing in decline, tourism is one of the few long-term bright spots.

Others share his enthusiasm. Veteran scuba diver Jackie Hildering works with the Marine Education and Research Society in Port McNeill, B.C. She specializes in photographing kelp and was keen to explore the waters near Hope Island for the first time.

As she put on her scuba gear, she promised to quickly come back with a kelp-eating sea urchin. Thirty minutes later, she returned to the surface after spotting plenty of other sea life but no urchins.

"The otters have done their work here," she said while still in the water.

"I went down thinking I'd be back in a minute. How crazy is it not to be able to find a purple urchin?"

Hildering detailed how the waters near Hope Island differ from areas where there are still no sea otters. She saw expansive kelp forests close to shore, sheltering a wide variety of fish including herring, different types of rockfish and swimming scallops.

"What I just experienced as a diver, was diversity.

"If only those worried about otters could see this," she said, connecting the underwater dots linking kelp beds to a wide variety of sea life.

It's a phenomenon that's been documented by Linda Nichol, the lead sea otter research biologist for Fisheries and Oceans Canada at the Pacific Biological Station in Nanaimo.

"It's an interesting story. It's a quite complex story,” she said of sea otters.

"They have this profound and incredible role in the ecosystem where they can literally flip the ecosystem from one system to the other."

Nichol said the otters are simply playing out their evolutionary role, but it "creates conflict with people who want shellfish."

"It's a very complex issue and we'll see how it unfolds," she said.

The interaction between species was on full display as CBC News tagged along during Erin Foster's otter survey in the Queen Charlotte Strait near the northern tip of Vancouver Island in early July.

As the boat moved slowly along the shoreline, more than once those on board were caught off guard by the sudden rush of air from the lungs of a humpback whale surfacing nearby. A huff or two of breath and it would dive back into the deep in search of food.

Small bait fish such as herring and needlefish popped from the surface as they attempted to evade attackers below. Salmon, too, were jumping as they made their way along the coast to freshwater to spawn. What was seen on the surface only hinted at what was happening below, out of sight.

Relatively few people venture this far north, past the end of the roads on Vancouver Island, where the coast is harsh and wind-blown seas batter the coastline. The landscape is mostly steep and rocky, often appearing monochromatic, framed by a grey sky overhead and steely ocean below. The trees fighting for survival are stunted and gnarled, branches flattened by all-too-frequent gale-force winds.

It's a place where the constant churn of water from the open Pacific meets land, sparking countless interactions between plants, animals, algae, fish and birds. A balance where the sea otter is once again part of the mix after a long absence.