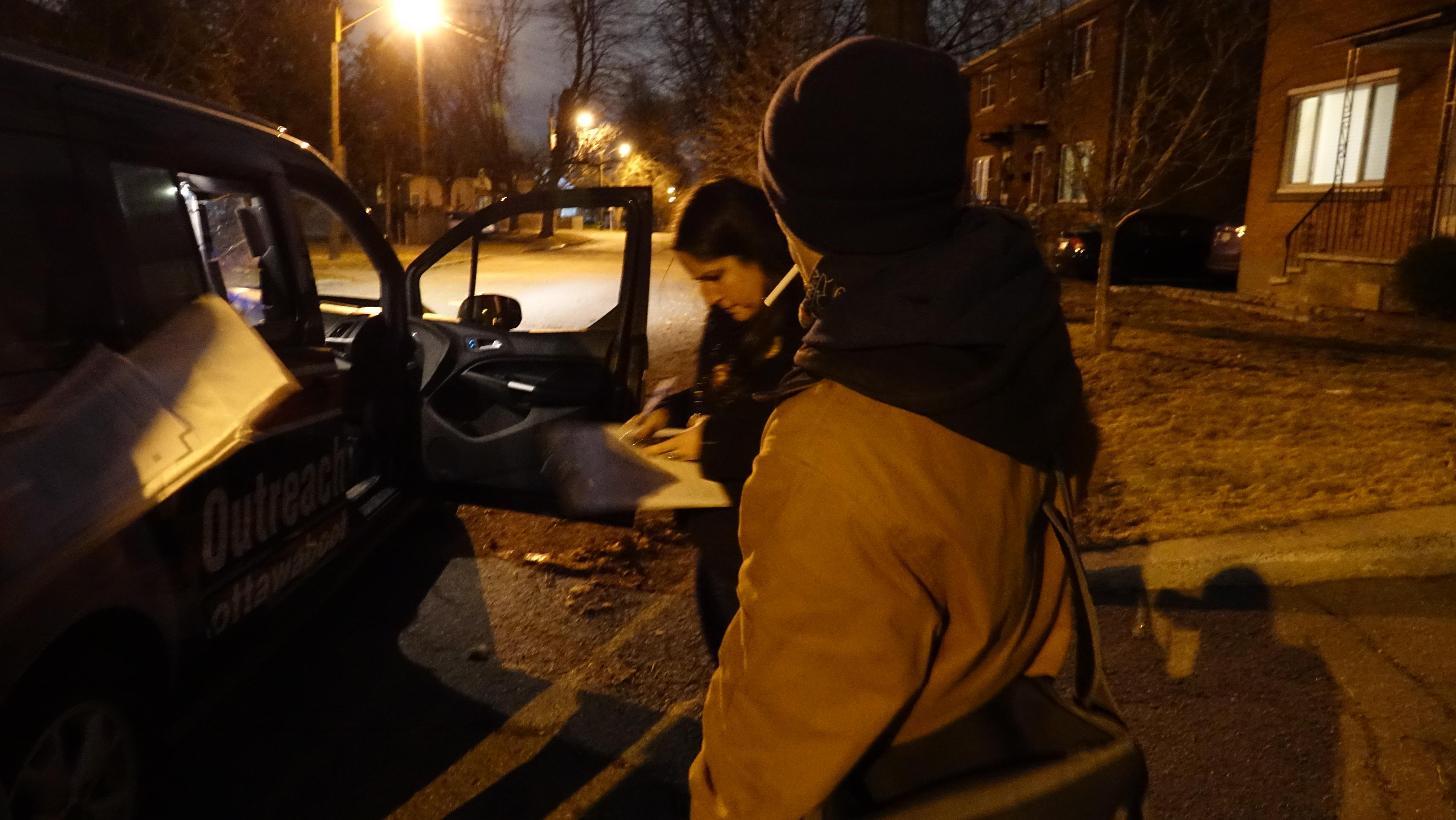

It’s 9 p.m., and Natasha Dharshi and Kristen MacDonald are steering the Salvation Army outreach van through a residential neighbourhood, looking for homeless people.

They see a young couple out for a stroll and stop to ask if they’ve seen any.

“We’re homeless,” comes the reply.

The couple look like typical neighbourhood teenagers, but Dharshi and MacDonald soon learn they’re living nearby in a shed, a thin blanket their only protection from the unseasonably cold spring weather.

A few weeks ago the couple had a tent and sleeping bags, and were camping out in a city park. But when their gear was stolen they were forced to seek shelter in a 24-hour McDonald’s, where they tried to stay up all night before catching as much sleep as they could during the day.

Finally, they found the shed. To them, it was a haven.

What’s perhaps most troubling is that their story is all too common in the capital.

It's the first time there has been an official census of Ottawa's homeless population. Laura Osman tagged along on a special 24-hour count on the streets.

The city gathers all kinds of information about the people who stay in homeless shelters and frequent food banks, but very little is known about the homeless people who don’t use those services.

For the first time, 75 social agencies banded together last week under the direction of the city in an attempt to find out how many homeless people were really inhabiting Ottawa’s nooks and crannies.

Over a 24-hour period, hospitals, emergency shelters, food banks and several other organizations handed out an anonymous survey to anyone who identified as homeless. Those who agreed to participate got a $10 Tim Hortons gift card, which to them meant a meal and a warm place to stay for a few hours.

City of Ottawa to count, survey homeless residents

Dharshi, MacDonald and the rest of their team at the Salvation Army were handed the more difficult task of rooting out the city’s hidden homeless population — those who don’t seek out social services, whose struggles are often kept secret.

The city estimates there are currently 25 homeless people living outside of emergency shelters in Ottawa. Dharshi and MacDonald tracked down and learned the stories of 12 of them.

Between them, they have plenty of experience: Dharshi is the supervisor of the Salvation Army’s outreach services and MacDonald is the director. Even so, the search was gruelling. They spent 11 hours driving and walking downtown streets, residential neighbourhoods and parks.

Sometimes the symptoms of homelessness are obvious: Dharshi and MacDonald waved down people carrying lots of bags, and people with dirty clothes and disheveled hair.

Often, homelessness is far more difficult to spot.

“In my experience, a homeless person can look a lot like you and I,” Dharshi said. “You can never really know what a homeless person looks like.”

So the pair also asked people who didn’t appear homeless whether they had a safe place to sleep that night. They poked behind bushes and peered down alleyways for signs of sleeping bags or blankets. They traipsed through the backyards of rooming houses strewn with garbage and old mattresses, and ventured under bridges.

When they found what they were looking for, the stories they heard often involved addiction and mental illness. But there were as many stories as there were people.

One woman who had recently arrived from Montreal had only become homeless a week earlier, and said she didn’t know where she would stay that night. A man sitting on a stoop said he routinely sleeps outside because he doesn’t like the crowds at the shelters.

There was a couple who didn’t want to go to a shelter because it would mean leaving their dog behind, and who desperately needed food for their pet.

Each time Dharshi and MacDonald took down a person’s story, they tried to help in any small way they could.

MacDonald was able to track down some kibble for the couple and their hungry pup. And the Salvation Army found the young couple in the shed some warmer blankets and fresh socks.

“It’s never easy to leave a young couple after you connect with them, knowing that they’re going to be sleeping in a shed,” Dharshi said.

But by simply taking the time to find these people, the outreach workers may have made a difference in their lives.

Through that initial contact, some have now entered the social services system, which could one day lead to stable housing.

“There’s a lot that’s going to happen behind the scenes,” MacDonald said.

The city is preparing to process thousands of surveys collected during the 24-hour homeless count. It won’t capture everyone who needs help, but workers are hoping it will lend them a clearer picture of the need for resources.

The survey results will be shared with the federal government as part of the national housing and homelessness strategy. The final tally and analysis will be released this summer.

Still, many agencies are battling strict mandates that don’t give them the flexibility to help people in different situations, including so-called “couch surfers” and other hidden homeless.

MacDonald says that can be frustrating, but there’s always someone else waiting in line.

“We have 70-year-olds that are on the street, we have pregnant youth,” she said. “You gotta take the highest priority first.”

Can Ottawa really end homelessness?

By midnight the outreach workers are ending their count, and the young couple are possibly asleep in the shed, thankful for the new sleeping bags.

Exhausted, Dharshi and Macdonald were hopeful that the work they did tonight will mean fewer people living on the street in the future.