February 22, 2021

WARNING: This story contains graphic content.

For years, Jennifer Van Der Zander stayed silent because she thought she had too much to lose.

But the civilian employee with the Ottawa Police Service has reached her limit, six years after becoming caught in a twisted triangle of sexual harassment she says threatens her husband’s police career, and her own.

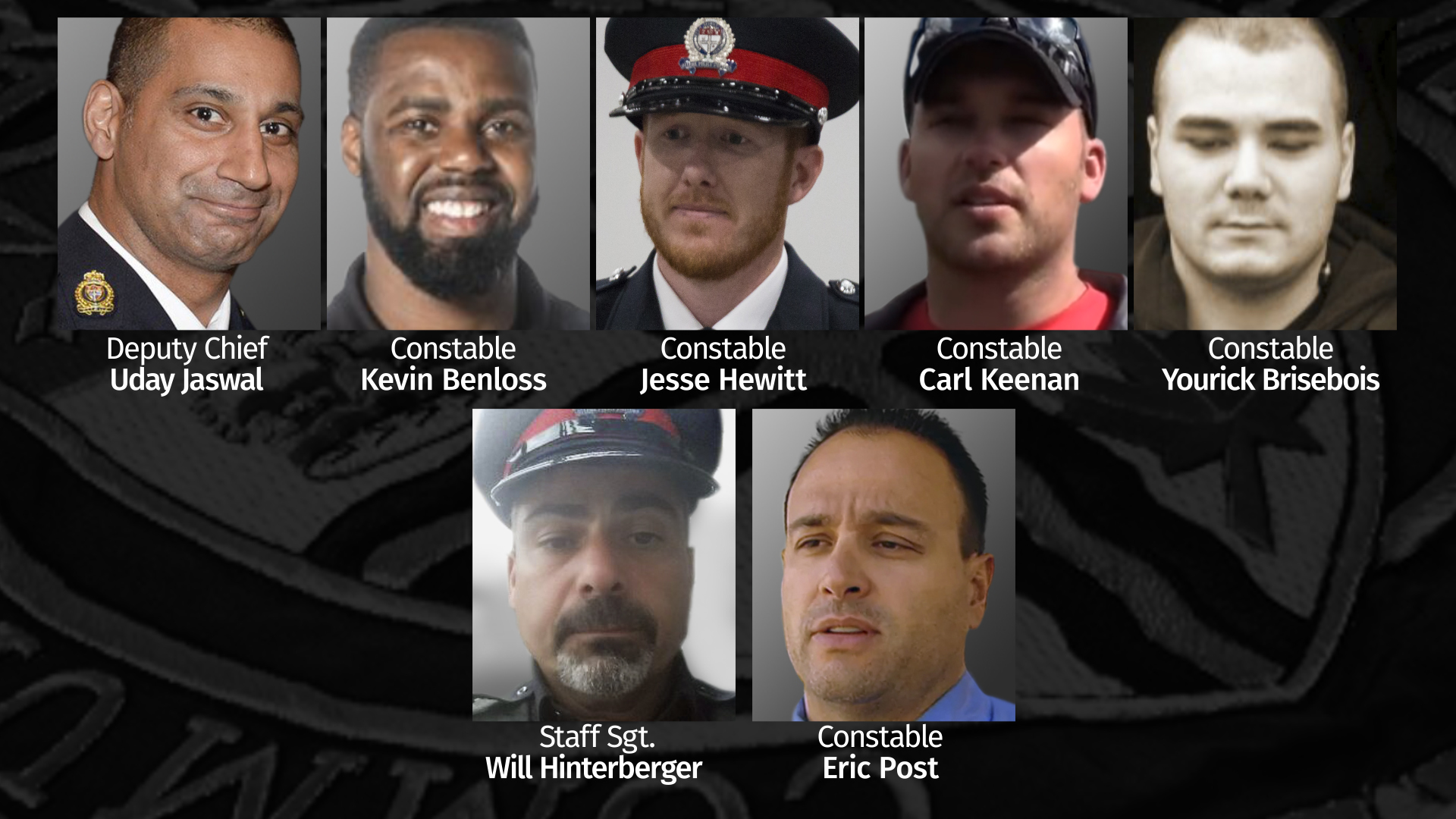

Van Der Zander filed a human rights complaint against the Ottawa Police Service in 2019. It triggered an investigation and resulted in Police Service Act charges against Deputy Chief Uday Jaswal, her husband’s commanding officer.

"I want to shine a light on the fact that not just specifically what Deputy Chief Jaswal did, but just that this kind of behaviour — no woman needs to tolerate it," said Van Der Zander.

"You cannot do this and you cannot get away with it."

Van Der Zander is one of at least 14 women, both sworn officers and civilian employees, who have reported being sexually abused or harassed by Ottawa police officers in the past three years.

From casual sexism such as being called "fresh meat" to more serious claims such as forced masturbation and rape, CBC's The Fifth Estate has found an entrenched culture of sexism that raises questions about how complaints are investigated, and in some cases, according to the women, even suppressed within the Ottawa Police Service.

- Watch The Fifth's Estate's documentary "Exposed: Sexism within Ottawa police" on CBC Gem, the CBC's streaming service.

The Fifth Estate spoke to seven women about the abuse they say they faced. Three are officers, two are civilian employees and two are members of the public who dated cops. Their complaints have led to criminal and misconduct charges in five cases.

Their allegations implicate every rank of officer, and Van Der Zander’s story reaches into the highest levels of the police chain of command.

I. The twisted triangle

In her complaint to the Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario, Van Der Zander said she respects and admires law enforcement professionals but that her interactions with Jaswal have damaged her trust in persons of authority.

In her claim, Van Der Zander describes herself as "merely a pawn in [Jaswal’s] end game of personal sexual gratification" and that she was perceived by him as an "easy target."

In his response to her claim, Jaswal admitted to being romantically interested in Van Der Zander, but claims she didn't tell him upfront that she was involved with someone else.

The alleged harassment began in the summer of 2015 when Jaswal became the new superintendent responsible for security at the courthouse where Van Der Zander worked as a court liaison.

She considered Jaswal an acquaintance but not a friend.

According to her complaint, she received a surprise cellphone call from Jaswal in June of that year inquiring how she was doing since reporting a past sexual assault. She had not given him her personal cell number and was stunned that he knew such deeply personal information about her. Van Der Zander believes Jaswal inappropriately accessed her records as a means to get close to her.

Six months later, Jaswal called her to meet for a coffee. She agreed, believing it was to discuss work-related issues. Instead, he told her he wanted to date her.

Van Der Zander said she clearly told Jaswal that she was in a serious relationship with another police officer, and that they were planning to move in together and merge their families. Despite her blunt words, Van Der Zander said Jaswal continued to ask her out over texts and even dangled the prospect of helping her get a promotion.

"It made me feel ... that he didn't respect me," said Van Der Zander. "It also made me feel professionally that I'm in a vulnerable position; that he’s relating advancing my career to dating him."

WATCH | Ottawa police employee recalls inappropriate conversation with deputy chief:

The months of harassment put stress on Van Der Zander’s relationship with her then-boyfriend, Peter Van Der Zander, an Ottawa Police Service sergeant, who she later married.

Peter Van Der Zander first approached Jaswal with his concerns in the hallway of the courthouse, but was brushed aside.

"I initially was going to go back to my desk and I couldn't. I thought about our family. I thought about our four kids and I said you know what — as much as my career is important to me, my family’s more important to me and this needs to stop," Peter Van Der Zander said.

Later, he barged into a room where Jaswal was meeting with two other senior managers.

"I turned directly to the superintendent in front of my boss, and in front of my boss's boss … I said the sexual harassment of my [partner] has to stop."

Peter Van Der Zander walked out of the room, fearing he had committed "career suicide."

Ontario’s Bill 168 mandates that employers take steps to protect their staff from harassment, but the Van Der Zanders say nothing happened.

WATCH | Ottawa police sergeant recalls telling commanding officer to stop sexual harassment of his wife:

At the same time, Jaswal's star kept rising. In the summer of 2016, he was hired to be deputy police chief in Durham Region, east of Toronto.

"Nothing is ever getting done. He now has more power. But he was gone," said Jennifer Van Der Zander. She was relieved that Jaswal was leaving Ottawa, but angry at the lack of accountability.

Controversy dogged Jaswal during his tenure in Durham. He was among a group of senior officers accused of corruption and abuse of power. The allegations are still under investigation. The Ottawa Police Services Board hired him back and installed him as the city's deputy chief in 2018.

Floored by Jaswal's return, Van Der Zander did her best to avoid him until their paths crossed at a staff luncheon in January 2019. While she was standing by the coffee area chatting with a co-worker, the deputy chief walked across the room toward her.

That's when, according to her human rights complaint, Jaswal "intentionally and overtly rubbed his hand across her stomach and hip area."

"There's no way that the deputy chief enters this gathering and does that. It’s incomprehensible," said Van Der Zander. "It's like he had a sense of entitlement to just do whatever he wants to whoever he wants…. It's disgusting."

Following that incident, Van Der Zander hired human rights lawyer Paul Champ.

II. ‘#MeToo moment for the Ottawa police’

Champ views the current case against Jaswal as a moment of reckoning for the force.

Jaswal was widely viewed as a homegrown contender to be the force's next leader. He had both hard and soft policing skills — experience in the guns and gangs and drug units along with extensive community outreach work over two decades with the OPS.

"The fact that someone could rise to that level in the Ottawa Police Service and would still feel that they could engage in that kind of behaviour, still feel it's safe or acceptable for them in that kind of behaviour, gives you a sense of how deeply rooted those kinds of norms are in the organization," said Champ. "This is a #MeToo moment for the Ottawa police."

After Jennifer Van Der Zander filed her human rights complaint in September 2019, the Ottawa Police Service board asked the Ontario Civilian Police Commission (OCPC) to investigate her allegations of sexual misconduct.

Jaswal declined CBC's request for an interview, but his lawyer, Ari Goldkind, said he will defend himself vigorously.

In his statement of defence, the deputy chief said he once dated Van Der Zander's roommate and they had previously hung out in group settings. They were connected on Facebook and Instagram and he considered her a "friend and a confidant."

He said he was romantically interested in her, but Van Der Zander didn't immediately tell him she was in a relationship. In his response, he acknowledges that he awkwardly touched Van Der Zander at the staff luncheon after stumbling into her in a tight space.

Jaswal knew that Van Der Zander also had hopes of making the leap from being a civilian to a constable. In his statement of defence, Jaswal alleges Peter Van Der Zander tried to pressure him into intervening in the selection process to get his wife recruited by threatening to reveal past text conversations between her and the deputy chief.

He alleges Jennifer Van Der Zander filed her human rights complaint as an act of vengeance after her husband's attempt to blackmail him failed.

"The complaint made by Jennifer Van Der Zander was filed after the deputy chief refused to give in to her husband’s threats and demands that she be hired," Goldkind wrote in the statement.

"Allegations of wrongdoing by the deputy chief should be approached with great caution."

In March 2020, seven months after Van Der Zander filed her complaint, the Ontario Civilian Police Commission charged Jaswal with insubordination and discreditable conduct. The board suspended him with pay.

Other women have also complained of alleged sexual harassment by Jaswal as far back as 2008. In addition to Van Der Zander, two female officers have filed complaints with OCPC. Jaswal did not comment on those allegations because he had yet to see their disclosure files at the time. The deputy chief now faces six counts of discreditable conduct and insubordination under the Police Services Act.

WATCH | Human rights lawyer says Ottawa police are caught in a #MeToo moment:

III. Other suspensions and complaints

While Jaswal is the highest-ranking Ottawa Police Service officer accused of misconduct, he is not the only one.

As of last week, eight officers have been suspended with pay after being accused of violence or misconduct involving women.

In July 2020, Const. Carl Keenan was convicted of assault causing bodily harm after knocking a woman unconscious during an overnight camping trip. Following his criminal conviction, Keenan, a "coach officer," is now being investigated internally for sexual harassment.

Const. Kevin Benloss faces charges under the Police Services Act for discreditable conduct and insubordination related to an alleged off-duty sexual assault of a rookie officer a decade ago. Prior to being charged, he played on the OPS Hoopstars basketball team. The team was part of a strategy to build relationships in racialized neighborhoods and recruit diverse candidates.

Const. Jesse Hewitt faces nine counts of discreditable conduct under the Police Services Act. Part of the internal investigation into his activities involves allegations he took videos of mentally unwell women while on patrol and shared them with his platoon.

Const. Yourick Brisebois is charged criminally with uttering threats and assault with a weapon.

Staff Sgt. Will Hinterberger faces 21 charges including sexual assault, aggravated assault and forcible confinement.

Const. Eric Post was initially charged with 32 criminal offences in relation to seven women, among them sexual assault, criminal harassment and forcible confinement. The defence and Crown brokered a plea deal after the sudden death of one victim who accused him of a sexual assault and pointing a firearm at her. Post pleaded guilty last month to four counts of assault and one count of uttering threats.

In mid-February, Ottawa police said an eighth officer was charged criminally with four offences related to violence against a woman. The charges include two counts of assault, mischief and careless storage of a firearm. The officer, Const. Brandi Fraser, is a detective with the Ottawa Police Service guns and gangs unit.

Champ, the human rights lawyer, said it's likely there are other examples of misogyny and misconduct that haven’t surfaced.

"Making a complaint against an officer is seen as a betrayal," said Champ. "And very frequently what happens is women who come forward are branded as whiners, as complainers, they suffer reprisals that are overt — that anyone can see. So I think many women officers just decide it's safer and better that they just keep quiet."

Misogyny runs deep and wide among police forces. A former Supreme Court of Canada justice found that the RCMP tolerated "misogynist, racist and homophobic attitudes," and forced the federal government to pay out more than $125 million to compensate victims.

The Toronto Police Service is dealing with nearly 40 complaints of sexual misconduct against its officers.

And across Ontario, there are 38 human rights complaints alleging systemic sexual discrimination and harassment within police forces.

IV. To silence and suppress

Some of the women who work for the Ottawa Police Service, interviewed by The Fifth Estate, have kept their abuse hidden for years, wracked with guilt and shame. Others were discouraged from reporting. Because they are victims of sexual violence, CBC is using pseudonyms to tell the womens' stories unless they consented to being identified.

Carol, a former police dispatcher, is still struggling with the trauma of sexual assault she said she faced and that she kept quiet for half her career.

In early 2000, after a particularly intense stretch of work ensuring that the emergency communications system wouldn’t crash during the changeover to the new millennium, she was invited to what she thought was a staff retreat at Mt. Tremblant in Quebec. But when she arrived at the cottage, she realized there were only three people on the ski trip: herself, a staff sergeant and an inspector.

"These are people I consider my friends as well as my supervisors. What could go wrong honestly? We’re here to ski."

But Carol’s sense of security faded in the middle of the night, when a towering shadow darkened her bedroom door.

It was her staff sergeant. He was stark naked, she said, and walked over to her, grabbed Carol’s hand and forced her to masturbate him. He then climbed on top of her, tried to kiss her and fondled her.

"I was saying everything I could to make him stop. I said: 'What are you doing? You’re my boss….' I said: 'I know your wife.' "

Carol said he stopped assaulting her only at repeated mentions of his wife's name. After he stomped out of the room, she propped a chair under the door knob to prevent him from coming back in. She said she spent the rest of the night crying, slumped on the floor.

WATCH | Former Ottawa police dispatcher describes how she fought off a sexual assault:

That assault was a painful memory she said she tried to suppress for more than 15 years by turning to alcohol and opioids. In 2016, a year before she retired, as part of her healing process she decided to report the assault to the police chief at the time, Charles Bordeleau. She said she was stunned by the cold, clinical response she received.

“He did not want to hear what happened because he didn’t want to be a witness to the event,” said Carol, who says the chief cut off their conversation and instead told her to report it to the sexual assault and child abuse unit.

In an email, Bordeleau acknowledged the meeting with Carol, but declined to make further comments.

Carol said the first officer assigned to her case didn't seem to believe her, so she asked to speak to another detective. It took five months for another sexual assault investigator to be assigned to her case.

At the time, she also confided in a different supervisor, who persuaded her not to move forward with charges. She remembers him saying: "Your name could come out — they’ll drill you about your past boyfriends and relationships." He asked: "Doesn’t your son want to be a police officer?"

He gave her contact information for victim support groups. To her knowledge, her case wasn’t referred to the Special Investigations Unit. According to protocol, the SIU is supposed to be notified when officers are accused of sexual assault.

"It's always about protecting the blue," said Carol. "Not one person said how disgusted they were that one of their blue brothers would do something like that to another employee."

V. Nowhere to turn

Like Carol, Anne kept her alleged sexual assault hidden for years because she felt she couldn't turn to anyone for help. When she did speak up, she said she was ignored.

When she was hired by Ottawa police in 2010, Anne likened it to winning the lottery. She considered herself strong and self-assured, but said her male colleagues couldn’t see past her physical appearance.

"When you enter a boys club like policing, they won't let you maintain any power. They did that by reducing me to my gender. They couldn’t see my other skill sets."

Anne said a staff sergeant once joked that he would give her time off to get "a boob job." Male constables told her that she made "everyone’s shortlist" of who they wanted to sleep with. Anne would hear officers talk about "bag a rookie" nights and wonders if she was a target.

In her first year of policing, Anne said she was sexually assaulted by a fellow constable after a night out at a bar. Instead of driving her home, he drove her to his house, where she alleges he raped her. It took her seven years to find the strength to report the incident.

In another instance, she said, after spurning sexual advances from her partner on patrol, he refused to back her up during a volatile traffic stop involving an impaired driver.

Later, a detective she dated began stalking her after they broke up. Despite telling her managers about her fears, Anne said they approved the transfer of the detective to her station.

"I think you worry first as a woman that people aren’t going to believe you, but [for female officers] the reality is they do believe you — they just don’t care," said Anne, who is on leave after being diagnosed with PTSD.

WATCH | Female Ottawa police officer describes sexism in the force:

Anne filed a 45-page human rights complaint in 2019. From her decade-long career, she named nearly 20 Ottawa police officers who she said have harassed, assaulted and ignored her complaints of sexual violence.

Ottawa Police have not filed a formal response to her human rights complaint, but last year they charged Const. Kevin Benloss with discreditable conduct in connection with her alleged sexual assault nearly a decade earlier.

VI. Reprisals and retribution

Officers are sometimes reluctant to report misconduct because they fear reprisals.

Peter Van Der Zander believes he is being punished by senior officers for standing by his wife.

Six months after Jennifer Van Der Zander filed her human rights complaint, her husband said his career went into "freefall."

After 17 years of an unblemished record, Peter Van Der Zander was abruptly relieved of his duties as a supervisor on Christmas Day 2019. He also received four complaints about his conduct as a sergeant. Later, he was transferred to a detachment on the opposite end of the city. All the disciplinary measures were authorized by the chief.

Earlier this month, more than a year after he received the complaints, Peter Van Der Zander was charged under the Police Services Act. He faced four misconduct charges for refusing to apprehend a suspected homeless shoplifter at a Marshalls store and one charge of neglect of duty for not leaving a patrol officer overnight to protect a scene where there were unsecured firearms.

He pleaded guilty last week to one count of discreditable conduct related to mishandling the shoplifting complaint. He has been docked 15 days of pay. He also agreed to refresher training on conducting a firearms investigation. All other charges were dropped.

Chief Peter Sloly declined The Fifth Estate's request for comment, citing the ongoing legal proceedings, but Van Der Zander said he got the message loud and clear.

"If you come forward with sexual harassment allegations against senior members of the Ottawa police … there are going to be consequences. Guard yourself accordingly."

He wrote a letter to the Ontario Civilian Police Commission alleging he's "suffering severe reprisals from specific senior officers within the Ottawa Police Service up to and including Chief Peter Sloly."

Van Der Zander also has the Ottawa Police Association in his corner.

Matt Skof, the association’s president, backed up Van Der Zander's claims to the OCPC.

"Without a doubt, all I see in this file is abuse. Abuse of authority and reprisal for a member coming forward. The chief is taking a side," Skof said in an interview.

The OCPC calls the allegations "deeply disturbing" and has requested all the chief’s emails and documents regarding the decision to discipline Van Der Zander.

Although he declined an interview, Sloly issued a statement through the force's lawyer.

Sloly said he has "zero tolerance for any workplace sexual harassment" and is taking concrete steps to drive change.

Last October, Sloly announced the hiring of the law firm Rubin Thomlinson, which specializes in workplace sexual harassment investigations. Sloly said access to an independent investigator would encourage more women to come forward to report incidents.

"We are creating a new opportunity to help our members, to help our women to feel more comfortable, more valued, more protected, more able to come to provide great value to this organization and the city," Sloly said while announcing the six-month pilot project.

In January, the Ottawa Police Association filed a grievance on behalf of its members after it discovered that some complaints against senior officers were being screened out.

The Ottawa Police Service said the law firm will only look at new complaints.

Cases that are already under investigation by its professional standards branch, its human resources department or the SIU are outside the mandate of Rubin Thomlinson. Complaints lodged by former Ottawa Police Service employees or involving retired officers are also outside its scope. In exceptional cases, the law firm will consult with an internal panel that includes senior police executives.

One female officer CBC spoke with said she decided not to complain about her staff sergeant's sexist remarks after finding out he was in line for a promotion to be an inspector.

Since being hired in October, Rubin Thomlinson is actively investigating two allegations of sexual violence and 14 other cases of workplace harassment. Two cases have been deemed outside the firm’s scope.

In an email, Rubin Thomlinson said client confidentiality prevents the firm from providing more details.

Skof said the hiring of the law firm doesn’t represent any substantive change in how the force deals with sexual violence complaints.

Rubin Thomlinson lawyers can’t compel officers to sit down for an interview. The law firm can't mete out punishment. It can only make recommendations. And if those recommendations involve charges or potential criminal indictments, those still have to be reinvestigated by professional standards officers or an outside police agency.

VII. Looking to a third party

When Kelly Donovan, a former Waterloo constable who researches police culture, was an officer, she was charged with misconduct after going to the board with concerns about internal abuses of power.

She said real change can only come about when female officers can turn to a third party without fear of reprisals. Donovan said that an outside investigator must have "absolutely no ties to the force they work with."

"As long as you leave it internal, you always run the risk that there could be implicit conflicts of interest — maybe relationships at one point in time within that workplace that could affect the outcome of a current allegation," said Donovan. She said the officers who commit sexual misconduct should also be named by their police force.

Meanwhile, Ottawa city council is also asking the Ontario government for the ability to suspend officers without pay if they're accused of serious offences.

That usually can't happen unless an officer is convicted of a criminal offence with a jail term.

WATCH |Whistleblower explains why officers found guilty of misconduct should be named:

Darryl Davies, a criminologist at Carleton University, said the board should go even further and demand the power to fire officers.

"It should be zero tolerance for sexual harassment. You'd be fired if [a member of the public] engaged in that [behaviour in the workplace]."

Davies said that the OPS board needs to demand more transparency on how these internal harassment complaints are being investigated.

"Women who are subject to this ... their lives are damaged by this. When they go into policing, they don't expect the people they have to fear are the ones that they have to work with in uniform."

But these solutions require amending Ontario’s Police Services Act.

Anne said that's a goal she will continue fighting for. She no longer perceives herself as a "victim," but as a witness to a crime that needs to be stopped.

"When I realize that women aren't safe within police walls, then women aren't safe anywhere in society and that is a huge motivating factor for me to remain working as a police officer. I don't think it benefits anyone but abusers if I walk away from this job."

Following the investigation by The Fifth Estate, Sloly sent a message to all the members of the Ottawa Police Service acknowledging the systemic issues revealed by CBC.

“They raise some critically important and very legitimate concerns that are core to our ability to truly own and sustainably fix these real and longstanding issues within the OPS, the justice system and broader society,” Sloly wrote in an internal email to 2,100 employees.

Sloly said these behaviours must stop because they cause harm to members, the reputation of the force and relationships with the community.

“How effectively we respond to these issues will define us as an organization.”

- Watch full episodes of The Fifth Estate on CBC Gem, the CBC's streaming service.

- For tips on this or any story, please contact reporter Judy.Trinh@cbc.ca