November 18, 2018

Warning: This story contains graphic descriptions of sexual assault that some readers may find disturbing.

The crush

In Grade 11, Laurie Howat had a huge crush on one of the most popular guys at Ottawa’s Bell High School.

They spent as much time together as possible, before school, after school and over lunch.

“He and I were connected at the hip,” recalled Howat, now 31.

Other girls were prettier and smarter, but he had picked her.

“I was head over heels for him. It made me feel so unique and special that he’d seemed to have chosen me out of everyone.”

Howat’s mother had died of cancer a couple of years earlier, and the relationship provided the emotional stability she needed. Finally, she didn’t feel so alone.

Often, their encounters would take place in the private office attached to the school’s band room. By the time Howat was 16, they were engaging in fondling, masturbation and oral sex on a daily basis.

He was Tim Stanutz, her music teacher.

Howat said it wasn’t until a decade after she graduated that she realized how unhealthy that relationship had been.

“The difference in age was 28 years between myself and Mr. Stanutz,” she said. “Thinking back then, I knew it was wrong, but the reason I thought it was wrong was because he was married, not because he was my teacher.”

In 2016, when Howat finally told her therapist about her former music teacher, she couldn’t have known the firestorm she was about to set off, or the web of secrets it would unravel.

By law, her therapist had a duty to report Howat’s story to the Children’s Aid Society and to police.

A month later, in May 2016, Howat filed a complaint against Stanutz with the sexual assault and child abuse unit of the Ottawa Police Service. Stanutz, an award-winning teacher and band leader, was charged with sexual assault and suspended from his job.

Within hours of the teacher’s arrest hitting the news, a second woman, four years older than Howat, came forward with a similar story, leading to more charges against Stanutz.

Then the floodgates opened.

Dozens of former students, men and women in their late 20s to late 50s, began sharing their stories of sexual abuse at Bell, raising questions about what exactly had gone on inside the west-end school, and how it had been allowed to continue for so long.

Lightning strikes twice

On May 6, 2016, Peter Hamer was scrolling through the news when he came across a story about sexual assault allegations against a Bell High School music teacher in the late 1990s and early 2000s. He immediately felt sick to his stomach.

Hamer, now 51, attended Bell in the 1980s, and had similar encounters at the hands of a different music teacher.

Hamer wondered how lightning could have possibly struck twice. At the same time, he felt a jolt of guilt.

“I know this is stupid, but I realize because of what I did, that put Stanutz in the school,” Hamer said.

Unwelcome advances

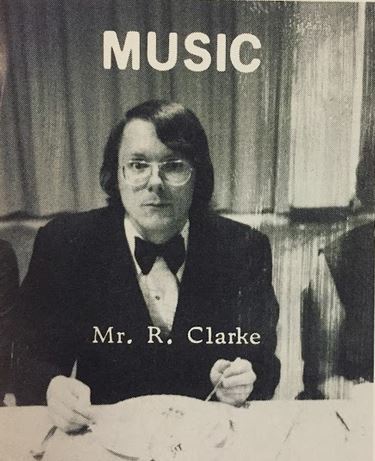

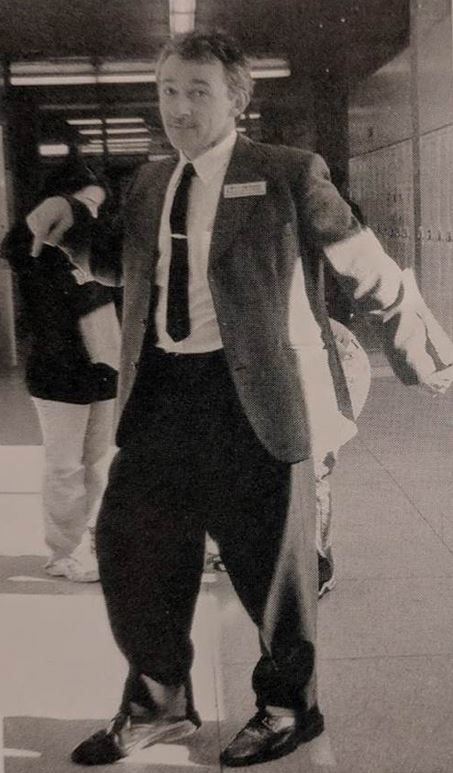

At first, Hamer found the band room a sanctuary of comfort and acceptance where he’d share lunch with his pals and their music teacher, Bob Clarke.

Clarke acted like one of the guys, eating french fries and joking around. Sometimes he’d tell sexually explicit stories that the teenage boys thought were a bit weird, but funny.

“He’d make comments about your body: ‘Oh, I can see your nipples through your shirt, you must be horny. Do you have an erection?’ It was the hugs, constant hugs. It was, ‘Oh, yeah, you dating her now? What do you do with her?’”

Hamer said his teacher soon began making inappropriate advances.

One time, on a bus trip, Clarke grabbed Hamer’s leg and asked if he could keep moving his hand toward the boy’s groin. That was just the beginning.

In the music department’s back office — the same room where Howat and Stanutz would later meet — Clarke offered Hamer better marks if he would strip naked and let the teacher take photos. Hamer refused.

Then one day, Clarke began masturbating in front of Hamer and invited the boy to join him. Again, Hamer said no.

“A couple days later in school, he called me into the back room and he asked me if I was going to keep his secret, and he asked me if I was OK, and I said, ‘I’m fine. That’s fine. I’m not saying anything to anybody.’”

But by the time Hamer was 18, in 1986, he was no longer fine.

(Michel Aspirot/CBC)

He was distraught about what had happened with Clarke, and he was worried about what might happen to his younger brother, who was due to start at Bell the following year.

Hamer went to then principal Patrick Carroll to report the abuse, and said he wanted Clarke gone.

By the following September, Clarke had been transferred to another school. His replacement was a talented young music teacher named Tim Stanutz.

“I don’t hold myself responsible,” Hamer said. “I’m just a piece in that chain of events.”

More allegations, more teachers

Within days of hearing about the charges against Stanutz, Hamer went to the police station to file his own complaint against Bob Clarke.

The first charges against Clarke, by then retired and living in Morrisburg, Ont., were laid on June 15, 2016. There were more disturbing allegations to come.

Four days later, on June 20, Ottawa police began investigating a third teacher associated with Bell High School.

Donald Greenham, a teacher at a neighbouring elementary school who coached basketball at Bell, would soon face more than 50 complaints of sexually assaulting, exploiting and threatening students between 1970 and 1981.

The chocolate bar

Bored by school and too bright to remain with his classmates, Franz Glaus skipped a grade in the 1970s.

Looking back, Glaus, now 58 and a longtime resident of Montana, remembers Greenham as a towering, intimidating man.

His first encounter with Greenham came when he was in Grade 8 at Bayshore Public School, where Greenham also taught. The teacher presented it as a game.

“It was called ‘the chocolate bar,’” Glaus recalled. “Pinning my arms back, [he] got me on a bench. I mean, this is right outside the principal’s office in the school.”

Greenham’s “game” quickly turned sexual.

“Donald Greenham actually grabbed my testicles. The idea was, you name a chocolate bar. If it was a crunchy chocolate bar, he would squeeze harder. If it was a soft chocolate bar, he’d relax his grip.”

When Greenham eventually let go, Glaus ran.

Glaus later heard that some of Greenham’s sexualized games and initiations in the locker room and on school canoe trips were much worse than the chocolate bar.

He would ask students to “tape their penises together — like, tie their penises up to a branch of a tree,” Glaus said.

And yet, none of the other adults seemed to notice. Glaus said that at that time, the basketball coach had a sterling reputation.

“Everybody loves Greenham. All the teachers think he’s great,” Glaus said.

He didn’t want to tell his parents about Greenham, and likely never would have if his mother hadn’t caught wind of what was going on.

The lioness

At 84, Madeleine Glaus is still a feisty mother with a sharp mind and an iron determination to protect children — and not just her own.

It was during a cottage weekend with her nieces in the mid-1970s that she first heard the rumours about the Bell High School coach’s propensity for touching the genitals of teenage boys.

Her nieces talked about a young boy who was molested on a canoe trip. The details were extremely unsettling.

She confronted her sons, by then attending Bell, to find out what they knew about Greenham. She quickly learned about Franz’s earlier encounter with the teacher.

“Then I say, ‘I’m going to do something about this man,’” said Madeleine Glaus, who now lives in Montreal. “He doesn’t deserve to be around kids because he’s sick. So I went to see the principal.”

She gave the principal at Bayshore one week to act.

Two weeks went by and she heard nothing, so Glaus and her husband decided to take the matter to the school board, then known as the Carleton Board of Education.

Board officials interviewed her sons, but the teenage boys felt too intimidated to share the names of other kids who’d been victimized by Greenham.

In the end, Glaus said her complaint had no effect. After some 40 years, she can’t recall the name of the school board official she first warned.

“You trust people. I trusted that man that I talked to, and he betrayed me,” she said, still angry after all these years. “[The victims] are traumatized. Even their minds are broken.”

Glaus approached other parents, too, but at the time, no one seemed to want to make waves. She was alone in her struggle to lift the veil on Don Greenham’s behaviour.

“She’s just a lioness,” Franz Glaus said about his mother. “I can remember her saying all those decades ago how cowardly people were, how they were willing to just let great offences take place.”

Shortly after Madeleine Glaus complained about Greenham, she saw the teacher and his wife walking down the street.

“I said, ‘Sir, you’re a very sick man. You have to go get help,’” she remembered. “No reaction at all. Nothing.”

The canoe trip

Dan Leeson believes he was the boy on the canoe trip that Madeleine Glaus heard about, the horrifying story that prompted her to confront her sons and go to school officials.

“It was the canoe trip at the end of Grade 7 with Don Greenham where my life changed,” Leeson said.

It began as an initiation prank, but ended with Leeson being pinned down by other boys while the teacher groped his genitals.

Leeson said the humiliation, guilt and shame he felt afterward led him to excessive drinking and drug use, which led to criminal charges and convictions.

“I tried to commit suicide when I was 14. I didn’t belong, and it took 40 years for this to come out, [when] Greenham was charged,” Leeson said. “This guy stole my soul.”

In 2016, Leeson filed a police complaint against Greenham for what had happened all those years ago.

Crossing paths

Between the mid-1970s and early 1980s, both Don Greenham and Bob Clarke led extracurricular activities at Bell High School.

Franz Glaus said he was victimized by both men, but chose not to lay charges against Clarke.

“One’s a band director, and a good one — he took our bands to city-wide competitions and we won them — and Greenham had great basketball teams and would win city-wide competitions. So these guys made their mark,” Glaus recalled.

Glaus eventually dropped basketball to concentrate on band, playing lead trumpet for Clarke.

One night, while driving Glaus home in his little yellow sports car, Clarke made his move, placing his hand on his student’s leg.

“He was testing me,” Glaus said. “I guess part of you is thinking it’s just for fun and kicks, because you don’t know yet that it’s a total perversion.”

Teachers charged

Shortly after another student complained about Greenham’s behaviour, Greenham left Bayshore and started teaching at another school.

He retired in 1997 as a winning coach with an unblemished teaching record, at least as far as school officials were concerned. After retirement, that reputation would buoy him to new, high-paying appointments to advisory boards for the province of Ontario.

The hammer finally fell in 2016, when complaints involving 22 former students led to more than 50 charges against Greenham for indecent assault, gross indecency and other offences.

In March 2018, just months before his case was to go to court, Greenham died. He was 75.

Several victims have launched a civil suit against the school board and the Greenham estate.

In a statement to CBC about the lawsuit, the board, now called the Ottawa-Carleton District School Board (OCDSB), wrote, “This is a difficult situation for everyone, and our thoughts are with those directly affected by this case.”

(CBC Archives)

Enduring mystery

The law eventually caught up with Bob Clarke, too.

In 1986, after Peter Hamer told the principal his music teacher had asked to take naked photos of him, Clarke was moved to nearby Sir Robert Borden High School.

Soon, fresh complaints arose.

In 1992, Clarke’s teaching career came to an abrupt end. Exactly why or how remains something of a mystery.

According to court documents, someone had alerted school administrators to Clarke’s “inappropriate sexual conduct with students.” The OCDSB said an investigation into Clarke’s conduct was launched, but he resigned before it concluded.

Several students and former teachers at Sir Robert Borden told CBC they were never aware of any investigation into Clarke’s behaviour at the time.

Victims say if it had been completed, their abuse might have been prevented, or they could have received psychological help.

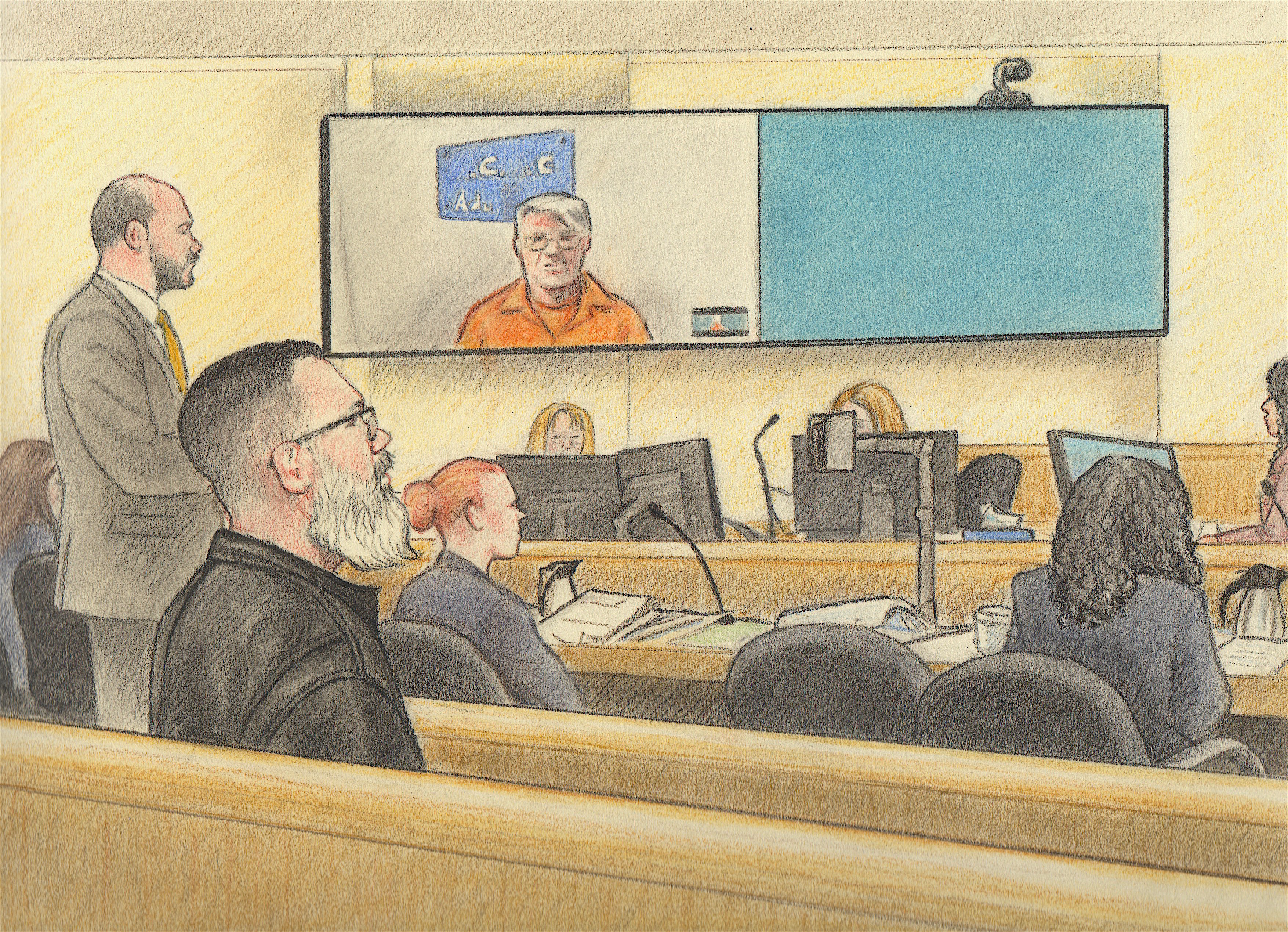

On March 21, 2018, Bob Clarke pleaded guilty to gross indecency and sexual assault of eight former students. He’s currently serving time in a federal prison.

A fiery crash

Tim Stanutz was still teaching at Bell High School when he was charged in 2016.

During his decades there he was known as a popular, charismatic and generous teacher. To this day, many of his friends and former colleagues believe there’s no way he could have hurt students.

But his victims say that’s exactly how he was able to get away with it.

In 2017, Laurie Howat was visiting her boyfriend in Texas when she got the call from an Ottawa police detective telling her Stanutz had died in a fiery, head-on crash with a dump truck.

Multiple police sources have described it as a suicide.

Stanutz’s preliminary trial was due to begin that August. Now, there would be no more court dates, no more interviews with police, no more victims given a voice. No more justice.

Stanutz’s reputation remained, for the most part, unblemished.

In an online obituary, one of Stanutz’s former colleagues wrote: “He was robbed of his honoured and heartfelt final farewell and musical bash at Bell, but our gratitude remains.”

Sledgehammer solution

Laurie Howat and Peter Hamer attended Bell High School 20 years apart, but they’re drawn together by that office beside the music room, and what happened to them there.

The two met for the first time this fall. There were some tears, some anger and some relief as they shared their stories.

“It would be very cathartic for us to go in with sledgehammers and get rid of that office, because there’s no need for it,” said Howat, who hasn’t been back to Bell since graduation.

“The back room, I wanted to brick it up,” Hamer said. “The space didn’t make them do it, but they took advantage of that opportunity. They need to get rid of the room.”

(Michel Aspirot/CBC)

Ripple effects

Depression, anxiety, thoughts of suicide. Difficulty with authority, trust, relationships and sexuality. They’re all among the long-term effects suffered by victims of historical abuse at the hands of their teachers.

When Howat first went to police, she worried about Stanutz, his wife and their children.

“We feel like it’s our fault. If we’d just kept quiet, people would be OK,” Howat says now. “I wasn’t living much of a life before, so I can’t imagine what any silent victim is going through.”

Franz Glaus left Ottawa years ago and allowed his memories of Bell High School to sink into the murk of time, but he’s welcoming the chance to dredge them back up.

“Thank God we’re having this discussion,” he said. “Stop hiding it, stop making excuses for it.”

Peter Hamer knows exactly what Glaus and Howat are talking about. He feels he kept quiet about Bob Clarke for too long. “You know, the most important thing for me is it's not my secret. It's now public, and it's not my responsibility to keep his secret anymore.”

Sexual assault resources:

Assaulted Women's Helpline 1.866.863.0511 http://www.awhl.org

Attorney General's Support Services for Male Survivors of Sexual Abuse 1-866-887-0015

https://www.attorneygeneral.jus.gov.on.ca/english/ovss/male_support_services/

Julie Ireton is an investigative reporter with CBC Ottawa. You can reach her at julie.ireton@cbc.ca

Correction:

In an earlier version of this story, the death of Tim Stanutz was described as a suicide. We have changed the text to attribute this information to multiple police sources. We also removed a quote from Laurie Howat that said the official police report declared the death was a suicide. CBC has been unable to independently confirm this information.