January 18, 2021

It was Wednesday, May 6, 2020. A few minutes before 11 p.m. It's a moment etched in the memory of the MacLean family.

Joel MacLean of Pictou, N.S., was playing video games with friends in his bedroom when he heard his mother, Denise, shout, "Oh my God!" She immediately started crying.

She had just received the call they had been waiting for. After 10 months on a transplant list, Joel was getting a new kidney.

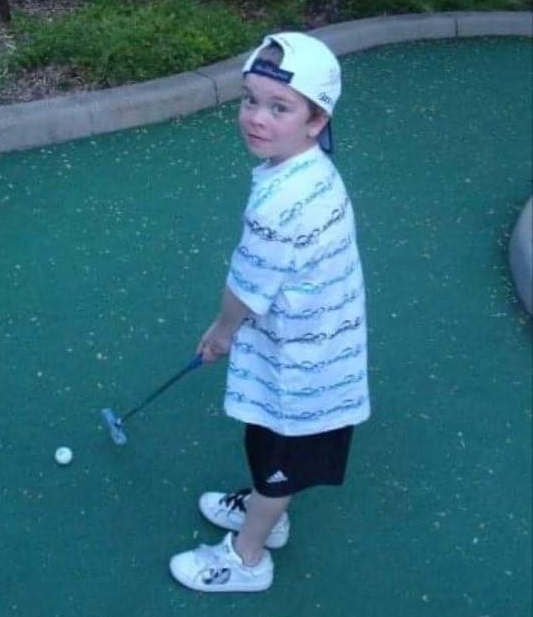

"It was surreal," said Joel, who is now 21 and suffers from congenital nephrotic syndrome, a condition he was born with that typically leads to irreversible kidney failure. "I was just dumbfounded, and I literally just sat there."

It was a sleepless night for the family. They raced to get ready, and then drove 165 kilometres from their home to the IWK Health Centre in Halifax. The next morning, Joel received his new kidney.

"You're fearful. You're happy that he's going to get the second chance," said Denise MacLean. "But then you also know that somewhere, someone else is going through the absolute worst time of their life."

For the MacLeans, Joel's transplant isn't about statistics or politics, but life.

That's what they hope people will focus on as Nova Scotia makes a significant change to the way it approaches organ and tissue donation.

On Monday, it becomes the first jurisdiction in North America to switch from an opt-in donation system to an opt-out system. It's a move that medical experts across the continent are watching with great interest.

Instead of signing organ donation cards, the system is now built around presumed consent — that every adult is open to being a donor when they die.

Those who are opposed can register on the opt-out list, and their families will also be able to make a decision at the bedside to stop the process.

And it's not for everyone. The rules do not apply to children, or those who lack the capacity to understand the concept. People who have lived in the province for less than a year are also exempt.

This movement for change began in 2017.

Nova Scotia had long been a national leader in organ donations until that point. But that year, the number of people who donated organs in the province suddenly dropped to a record low, just 16. It was nowhere near enough to help the dozens of people in the province waiting for an organ.

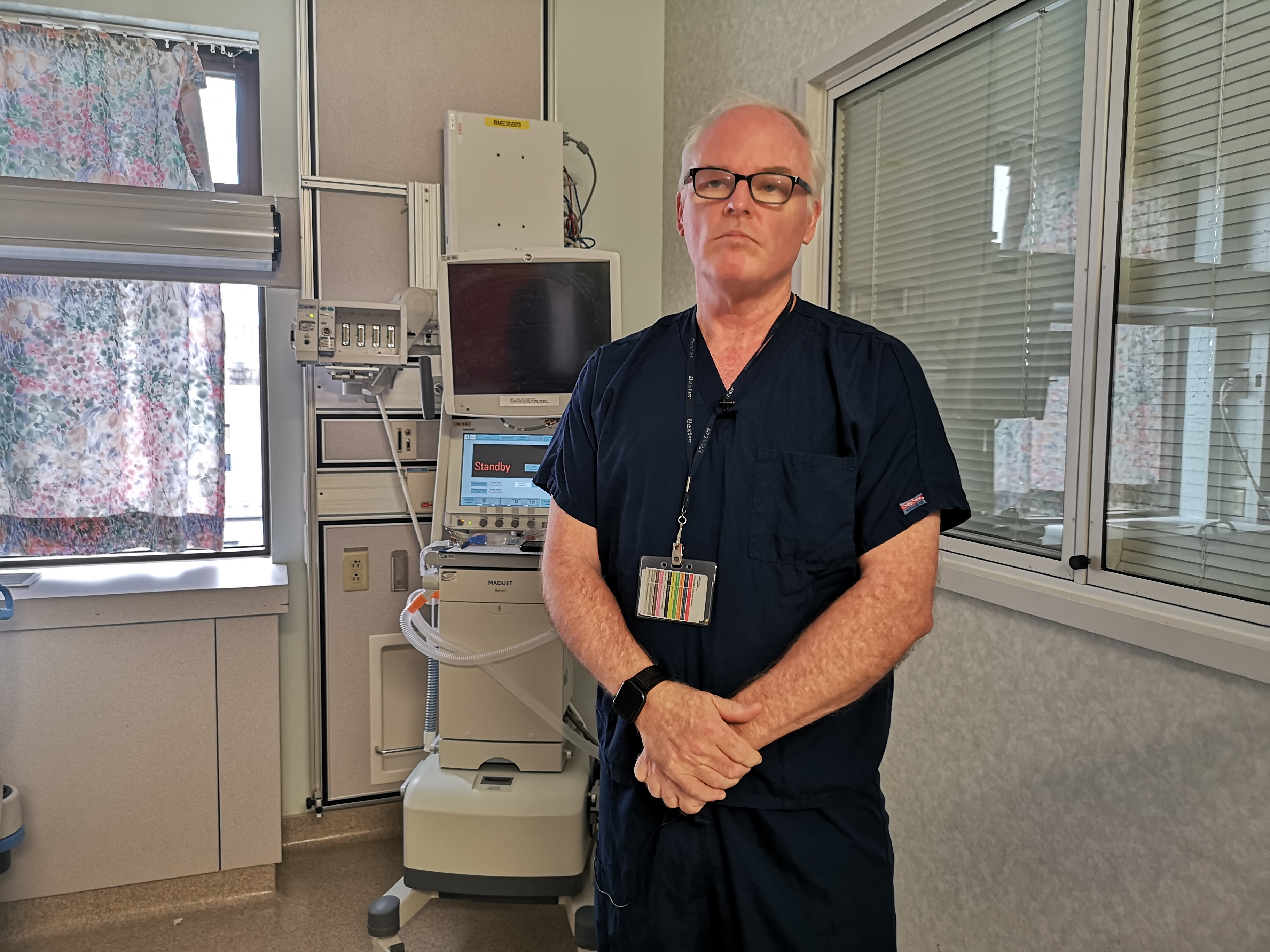

Dr. Stephen Beed was worried. He has been in charge of Legacy of Life, the province's organ and tissue donation program, since its inception in 2006.

He knew something had to change.

"So, as we started that conversation, around how to make our program better, we get a phone call from the premier's office," he said.

Nova Scotia Premier Stephen McNeil wanted to talk about presumed consent. He wanted to introduce a new law into the House.

The prospect was exciting for the specialist. Beed said researchers had done multiple surveys over the years that showed the vast majority of Nova Scotians supported organ donation.

The problem, he said, is that people weren't openly talking about their organ-donation wishes with those who would have to make the decision.

"To be honest, we had that situation in the last week where somebody had indicated they wanted to be a donor but the family did not provide consent," Beed said.

The doctor's hope, he said, is that this new law be a segue for families to bring up a conversation that many simply want to avoid.

Few people are comfortable talking about death, let alone in tragic or sudden circumstances. But clearly knowing someone's wishes beforehand can alleviate some of that struggle.

"It's hard to appreciate how difficult this can be without having experienced it," Beed said of what families go through.

"You haven't adjusted to the fact that your dad is sick and getting sicker, it's a sudden phone call. They're exhausted, they're stressed, they're scared."

It's been nearly 17 years since Margaret and Robert Miller found themselves in that impossible situation, but it's a feeling they'll never forget.

Pictures of their son, Bruce, are proudly on display in their Enfield, N.S., home, along with his police badge from the northern Nova Scotia town of Springhill, where he was a constable and worked as a school liaison officer.

In May 2004, the 26-year-old was driving to a lodge in Caledonia, P.E.I. The young police officer was there with a friend, hopeful he could get accepted into an RCMP training program.

But their vehicle was hit head-on by a 23-year-old drunk driver who was doing 178 km/h on the rural road.

Miller was taken to hospital in Moncton, N.B., and by the time his parents arrived, the prognosis was grim.

"They had told us that they thought he was probably brain dead, and then asked us in the next sentence if we would think about organ donation," said Margaret Miller.

"We hadn't had that conversation with our son. Who wants to have that conversation? How do you say, 'Well, if something happens to you, what should we do with your organs?'"

She was initially determined her son would pull through. But a few hours later, doctors confirmed Bruce was not going to make it. By then, his parents were ready to make a decision: they would donate his organs.

"For us, it just made sense to say, 'Bruce was all about second chances. He was all about trying to make the best of a situation.'"

A year later, Miller discovered her son had openly discussed with his friends that he wanted to be a donor. She says knowing his heart, two kidneys and his liver saved four lives helped with her grief.

"A 62-year-old man with a 26-year-old heart, he would have been leaping tall buildings," she said of one of the recipients. "These are lives, these are people, these are families that now have a new lease on life because of Bruce's gift."

Miller, who was elected as a Liberal MLA in 2013, shared the story of her loss in the Nova Scotia Legislature on April 12, 2019. That night provincial politicians unanimously passed the new donation law.

Several politicians from various parties have since called it one of the most important and proudest moments of their career.

"I couldn't stop crying, and I wasn't the only one," said Miller. "It really showed truly what government can be."

While the new law has received an outpouring of support, there are certainly naysayers.

Online forums have debated whether the government is going too far and is taking control of people's bodies.

There is also concern the province hasn't done enough to inform people of their options.

In the year and a half leading up to the law's enactment, Beed has heard it all. He makes it clear that people can register to opt out, and their wishes will be followed.

"That's their decision and we'll support them. What I don't want is people to choose to opt out because they're misinformed," he said.

"I've heard somebody say, 'Well, if I do this, the government's just going to take our organs and make money off them, so I'm not donating.' Well, that's coming to a conclusion based on completely erroneous information."

He points out that people are far more likely to one day need an organ than to donate. He said less than two per cent of hospital patients end up in a medical situation where they may be considered to become a donor.

"At any given time in Atlantic Canada, there's around 300 people who are awaiting an organ, most of them require a kidney."

The law, which was announced to much fanfare in 2019, has since been overshadowed by the pandemic. COVID-19 forced the province to delay implementation and give Beed's team more time to prepare.

Behind the scenes, Legacy of Life has been working with remote and minority communities to ensure they understand the changes.

They've also had to make changes within the health-care system, teaching more physicians to identify potential donors who in the past may have been overlooked because they were in a smaller regional hospital.

In some cases, families would find out long after their loss that their loved one could have been a candidate. In other cases, health-care workers who weren't trained to have conversations about donations did so in insensitive ways, leading families to reject the suggestion.

Now, regional employees are to call the Legacy of Life team based in Halifax, allowing it to take the lead and talk to families. Already, Beed said, that new network has resulted in more calls and more potential donors.

"I think the opportunity to transform the health-care system — I don't mean tweak it, I mean transform it — comes along very rarely."

Across the country, provinces reported a drop in organ and tissue donations after the pandemic began. There were fewer non-COVID-19 patients in intensive care, and some transplant surgeries were cancelled.

But in Nova Scotia, something astounding happened. It was the opposite. The province had 34 organ donors in 2020, a new record that pushed Legacy of Life beyond its goal of 30 a year within five years, achieved even before the opt-out law was implemented.

Beed said he thinks the new law has made families more aware, and made people more comfortable talking about their wishes. He has witnessed a difference in the conversations at the bedside, where fewer families are saying no.

"We've had by far the most successful donation year that's ever been recorded in Canada, to my knowledge," Beed said, referring to per capita numbers. "Frankly, it's remarkable. I'm hesitant to say it out loud because I want to have two or three years of success."

Among the recipients last year was Joel MacLean.

Before his transplant, he was constantly tired and slept all the time. He required weekly, painful injections. His mother worried he would become too sick for a transplant.

"Watching your child's health fail to the point that they are debilitated is heart-wrenching," said Denise MacLean.

"The late teens and early 20s should be a time when he was starting his life. To watch him not be able to do that and knowing that there is nothing you can do to make it better is devastating."

Joel's surgery in May was his second transplant. His first was when he was just two years old, when his mother donated her own kidney.

"As a parent, you'll do anything to save your child and to give them anything that they need to be healthy, to do anything at all," said Denise.

The family can also appreciate the difficult choice faced by a donor's family.

In 2015, Denise sat with her best friend after her husband collapsed from a pulmonary embolism. At just 41, he became a donor. His lungs saved the life of a man who was the same age.

The MacLeans don't know the identity of Joel's donor. But they think of the family often.

"This allows Joel to grow up. To truly live," said Denise. "He was living before, but the quality of life that he can have now with a fantastic functioning kidney is amazing. It's amazing for him."