September 30, 2020

When Emma Reelis was just 10, her father got sick. He died, leaving behind a wife and six young children.

It was 1958 and her father had been working at the military base in Happy Valley-Goose Bay, Labrador; her mother had few options.

"The minister gave my mother an ultimatum: you put your children up for adoption or you [send them] to residential school."

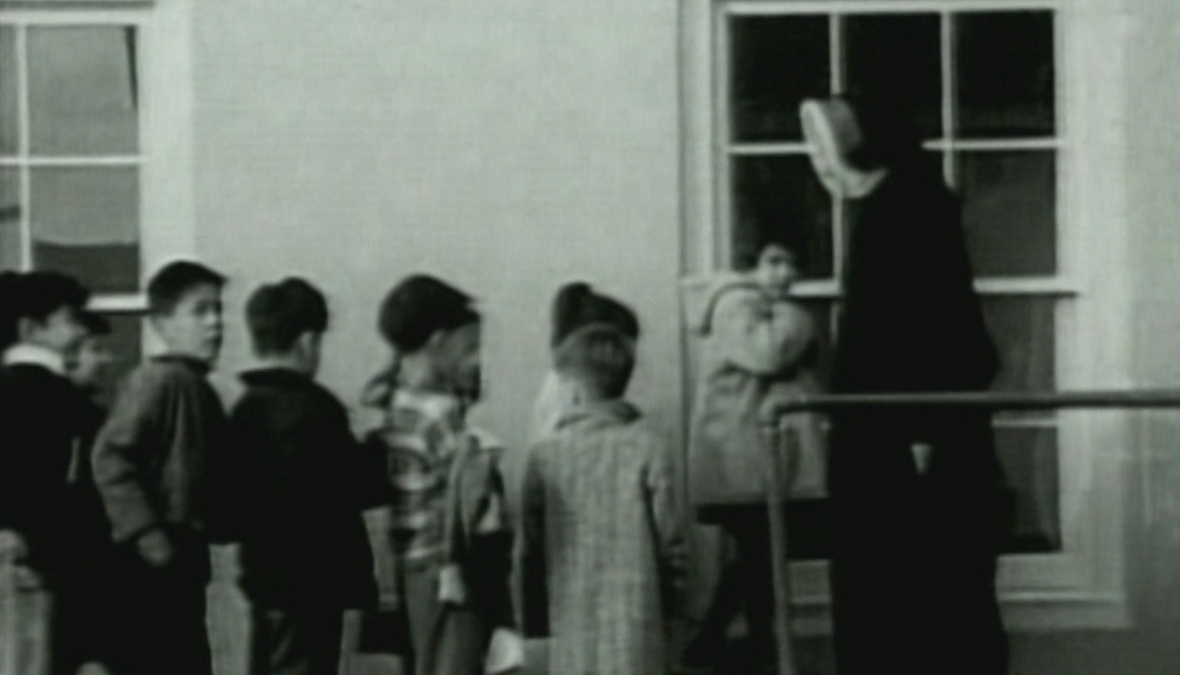

Residential schools were established by the Canadian government in the 1800s, with a guiding policy that has been called “aggressive assimilation.” The federal government sought to teach Indigenous children English and have them adopt Christianity and Canadian customs, and pass that — rather than Indigenous culture — down to their children.

Reelis was sent to the school in North West River, where she stayed in the dorms until 1963.

Those years of her young life were brutal.

"Down at the dorm you were told ... the impression that they gave you was, you were nothing, you're only an Eskimo person, you're not gonna amount to anything in your life, you're nothing, you know?" Reelis said.

It’s an experience that’s hard for her to put into words.

"You had abuse and ... mental abuse, physical abuse. And a lot of people went through sexual abuse. My sexual abuse happened one time ... but no one — I tried to tell people that I was sexually abused and I tried to tell my mother when I left school that I was, and she never believed me. No one believed me. 'You're telling lies, who's gonna believe you anyway?'"

When she was 16, Reelis left school and found a job at the community's nursing station. She eventually met her husband, who was working in Happy Valley-Goose Bay, and the two moved to his hometown of St. John's.

The treatment she received at the schools came to be what she expected for much of her life.

"I don't know how to explain it ... People were gonna talk about you and say what they wanted because that's who you are, and that's the way we were treated in the dorm,” Reelis said.

“You were just an ornament, I suppose, or someone to make fun [of] and belittle.”

As an adult, after years of not being believed about how she was treated in the schools, Reelis said she buried the memories.

It wasn't until years later, when the news emerged in the late 1980s of abuse at Mount Cashel Orphanage in St. John's, that her memories revealed themselves.

"When Mount Cashel came out, that's when my sexual abuse come out in me. That's how come I could talk about it — before, I would never. Because no one believed me," she said.

Reelis’s experience in residential school left her feeling isolated — and the legacy and enduring trauma Indigenous children experienced in the schools is an ongoing struggle.

The fallout of intergenerational trauma

Heidi Dixon is the business development co-ordinator at First Light in St. John’s, a non-profit organization that provides programs and services rooted in the revitalization, strengthening and celebration of Indigenous cultures and languages.

“The schools were created really to assimilate the Indigenous children and help fit them in with what people in power at the time wanted Canada to look like, so they were meant to westernize the kids, teach them English, have them find a good job was the idea behind them,” Dixon says.

“But really, they were horrible places where they were taken out of their homes, taken out of their communities. There was all kinds of abuse in the schools, they weren't allowed to practice their language or culture.”

While residential schools may feel like a dark part of Canada’s history, Dixon says they went on much longer than a lot of people realize.

In Newfoundland and Labrador, the last residential school was closed in 1980. The last one in Canada closed its doors in Saskatchewan in 1996.

Dixon says a large part of the enduring legacy of the residential school system is the intergenerational trauma it’s passed down.

"Intergenerational trauma is a really tricky topic to try to unpack,” Dixon says.

Essentially, it starts when someone experiences trauma as a child and internalizes that experience, Dixon says; it can manifest in people as poor coping strategies, mental health struggles, and feelings of shame, anger and alienation.

That then turns into a cycle and they pass that down to their own children, Dixon says — especially for people who were taken from their homes so young.

“Kids that went to residential school, they didn't grow up getting tucked into bed, they didn't grow up getting read bedtime stories, and so when they had their own children they didn't really know how to show them that they loved them. They did — they loved their children a lot — they just didn't know how to actively show them that,” Dixon says.

“So then that passes down more trauma, those kids don't experience the same kind of thing from their family members. They also don't connect with their language or their culture because their parents can't pass it down to them, and it creates this huge cycle.”

In order to move forward we need to talk about it — it's not a good part of history, but it is still a part of history.

It’s a complex issue with no easy solutions, Dixon says, but it’s essential to talk about residential schools and their legacy in order to understand them and spark change.

"It can really be a difficult conversation. Residential schools aren't easy to talk about, they're not fun to talk about,” she said, adding that First Light has many resources for people of all ages on their website.

“There's also all kinds of stories, videos and documentaries about people's experiences in residential school. They can be difficult to watch, but they're made for different age levels and those are easy to access."

Elder Emma Reelis talks about what residential school was like for her; Heidi Dixon explores why knowing the history of Canada's residential schools is so vital; and Dakoda Dicker talks about what she wants her peers to know.

Raising awareness is a key part of Orange Shirt Day, established in 2013 by survivor Phyllis Webstad and marked every Sept. 30 to honour residential school survivors.

Webstad was one of the tens of thousands of Indigenous children who were sent to residential school. Before she went off to school, her grandmother bought her a new outfit — a bright orange shirt to wear on her first day.

When she got to school, that shirt was taken from her and she never saw it again.

Dixon says that feeling of losing the shirt is symbolic of how Indigenous children felt attending the schools.

“They took away everything that she had with her, and she never saw the orange shirt again. So she always associated that orange shirt and the colour orange, really, with that feeling of not meaning anything to anyone, not belonging."

Orange Shirt Day has only recently been established. This year is only its seventh occurrence across Canada.

But Dixon says it signals a larger cultural shift, where Canada is learning to reckon with its history of mistreatment of its Indigenous people.

"I've definitely seen a change. I've been working with our Indigenous cultural diversity training program for the last five years or so and when I first started there were a lot of times I'd go into sessions and people had never even heard of residential schools, didn't know that they existed, didn't know that they were here in our province,” Dixon says.

“That seems to be less and less ... It definitely seems people have some more or an understanding.”

Dixon credits the work of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, the 94 calls to action that it published, and an increase in information and knowledge about residential schools — not to mention the strength of survivors who have since come forward to speak about their experiences.

In its efforts to boost the profile or Orange Shirt Day in Newfoundland and Labrador, First Light partnered with the Newfoundland and Labrador English School District on curriculum to be discussed in school on Sept. 30, including encouraging people to wear orange shirts.

This year, First Light also printed its own T-shirts, after holding an online contest with the theme “Every Child Matters” for kids to create the design to be printed.

This year’s design was created by Dakoda Dicker, 12, an Inuk student at Brookside Intermediate School in Portugal Cove-St. Philip’s, originally from Nain.

Dicker’s own grandparents went to residential school as children. When she attended middle school in Nain, Dicker learned a bit about the history of the schools, and wants others to do the same.

"In order to move forward we need to talk about it — it's not a good part of history, but it is still a part of history. It is also important to hear about the survivors' stories about residential schools,” she says.

"I feel really sad that children had to go through residential schools, many having so much trauma and experiencing abuse and losing their identity as an Indigenous person and not being able to talk in their own language."

Dicker intentionally left the faces on her design blank, to be more inclusive.

“I didn't draw faces on the children because the children could be any child, from anywhere,” she says.

“The children are holding signs that say 'Every Child Matters,' because every child does matter, no matter where you come from, what language you speak, or your beliefs and traditions."

Dixon said Orange Shirt Day will hopefully become larger and larger every year, with more people learning about residential schools. It helps that children are learning about them in school, ideally prompting conversations at home where parents may not have been taught that same history.

"I'd like to see the whole province in orange. It's a big ask, but I think the more people that get educated, the more promotion we have about it, the more education we have around residential schools, around our survivors, how strong and powerful our survivors are — I really would love to see more and more people doing it, more businesses, more non-profits,” Dixon says.

Having more people learn about residential schools is a huge step on the road forward, Dixon says.

“If we don't know what happened and where that's brought us, then we have no hope of ever getting out of that cycle."

For survivors like Reelis, it’s an enormously different experience to see people learning about residential schools and speaking openly about history that she herself experienced.

"Sometimes I feel uncomfortable talking about it even now,” she says.

“I'm 72 years old and to sit here and talk to you about all this stuff that went on in my life, from 10 years old to now, I even feel uncomfortable. But it's gotta come out, you know?"

Reelis still remembers what it was like to realize she wasn’t the only one to suffer at the schools — and what it was like to finally be believed.

"I just didn't bother people … I knew what I was going through, but I'd listen and listen to other people ... and I said, 'Gee, they went through that. I'm not the only one that went through that. Oh wow, I can talk about it more,’” she says.

“The more people talked about it, the more that I could come out about it. I guess a lot of people were that way, too ... once one person started, another person started, and I think that's how come it all came out. Just people that believed in each other."

For survivors who perhaps haven’t spoken about it, Reelis wants them to know they are not alone.

“What went on in the schools, that it wasn't your fault,” she says. “You didn't do anything wrong. We're human — we were only children."