July 17, 2018

Wood chips snap and buzz off Joseph Tobac's safety glasses as the sawmill blade rips through another log in Fort Good Hope, N.W.T., a fly-in community of several hundred people 800 kilometres northwest of Yellowknife.

Each pass of the saw strips timber and bark from the wood. Tobac shouts directions to his partner, Joel Lafferty, over the roar. Lafferty carefully picks out pieces of the cut wood, stacking two-by-fours off to the side as they're cut out of the log.

Fort Good Hope is surrounded by massive spruce trees — but lumber is a precious commodity.

Before the portable sawmill arrived this spring, it was nearly impossible to turn logs into boards suitable for construction projects, contributing to the community's ongoing housing crisis. Now, people in Fort Good Hope are developing the skills they need to work their way out of that crisis, using their own people and resources to do it.

"You're able to cut posts, beams whenever you need for a housing project with these boards," Tobac said.

Inadequate housing in Fort Good Hope has been an issue for years, long topping the list of problems for community leaders to solve. Many homes are overcrowded and in desperate need of repairs.

Roughly 50 single men and women — or about 10 per cent of the community's population of 515 people — are in need of a home, according to the community's latest housing report.

This is the case in First Nations communities across Canada. In 2017, the federal government began setting aside more than $1 billion for "improving Indigenous communities." But with the overall First Nations infrastructure deficit estimated at $30 billion, that's not enough.

That money hasn't had a meaningful impact in Fort Good Hope, which is why the Yamoga Land Corporation purchased the saw. The corporation manages funds from the Sahtu Dene and Métis land claim, signed in 1993.

Tobac runs the saw five days a week, building up the stock of lumber available to the fly-in community on the banks of the Mackenzie River.

See the Fort Good Hope sawmill in action:

He trained on the mill with four other people this spring and now trains others.

"I do like it," he said. "I've worked with wood my whole life, so it's something that's come naturally. You're able to build [any] possibility with it. There's a lot you can do with wood. It's fulfilling."

II.

Last December, the non-profit K'asho Got'ine housing society hosted a three-day forum on homelessness and housing in Fort Good Hope. The two main points were: homes are too expensive, and not enough people have the skills to keep them maintained.

Shipping costs alone mean even the most basic repair jobs often run into the thousands of dollars.

When the cost of shipping is included, materials cost contractors twice as much as in southern Canada. A truckload of lumber to Fort Good Hope generally costs between $15,000 and $20,000 when it's brought in on the winter road.

The sawmill was one of the first ideas to help make those costs manageable, explained Edwin Erutse, the president of the Yamoga Land Corporation, which funds the housing society.

"We're using our own people, our own resources from the land to solve this problem."

"Many of our people fall between the cracks," Erutse said. "Knowing we have a lot of resources out on the land, we said, 'You know what, why don't we invest in a sawmill, grab the bull by the horns and try to do something about housing.'"

The mobile mill cost the society about $100,000. It came in on the winter road earlier this year, and community members gathered the logs to build up this summer's supply. The Yamoga Land Corporation paid for the first 15 logs each person brought in from the bush.

"We're using our own resources from the land, our own people to do this. We want to do something about the problems we're having," Erutse said.

III.

Each day, Tobac and his partners add about 30 boards to the growing lumber yard outside town. About 250 have been cut so far, but there is no shortage of residents who need them.

Matthew Cotchilly is one of those people.

He's been living in a run-down home that his father built decades ago. He's found work on a local construction project and uses extra material from the project to fix up the house.

Cotchilly first spoke with CBC News in December, when he had difficulty keeping his house warm in temperatures as cold as –50 C, with ill-fitting doors and windows. Since then, he's turned it into a construction project of his own. He's set out a work area with tools on the bench and pieces of wood are ready to be installed.

"I'm fixing the strippings around the doors, I've put some new plywood on the ceiling, fixing the railings on the steps, insulating my doors and installing some shelves," he said. "My carpentry isn't going to stop until all this work is done.

"Life is pretty good. I'm not drinking," he said. "I'm staying sober and working. I'm trying to look after myself."

Even with these stories of progress, the housing crisis remains. Homelessness is not always obvious, as some people couch surf, stay with parents and find other ways to make do, even if they're homeless by most definitions.

Dozens of people still do not have an adequate place to call their own.

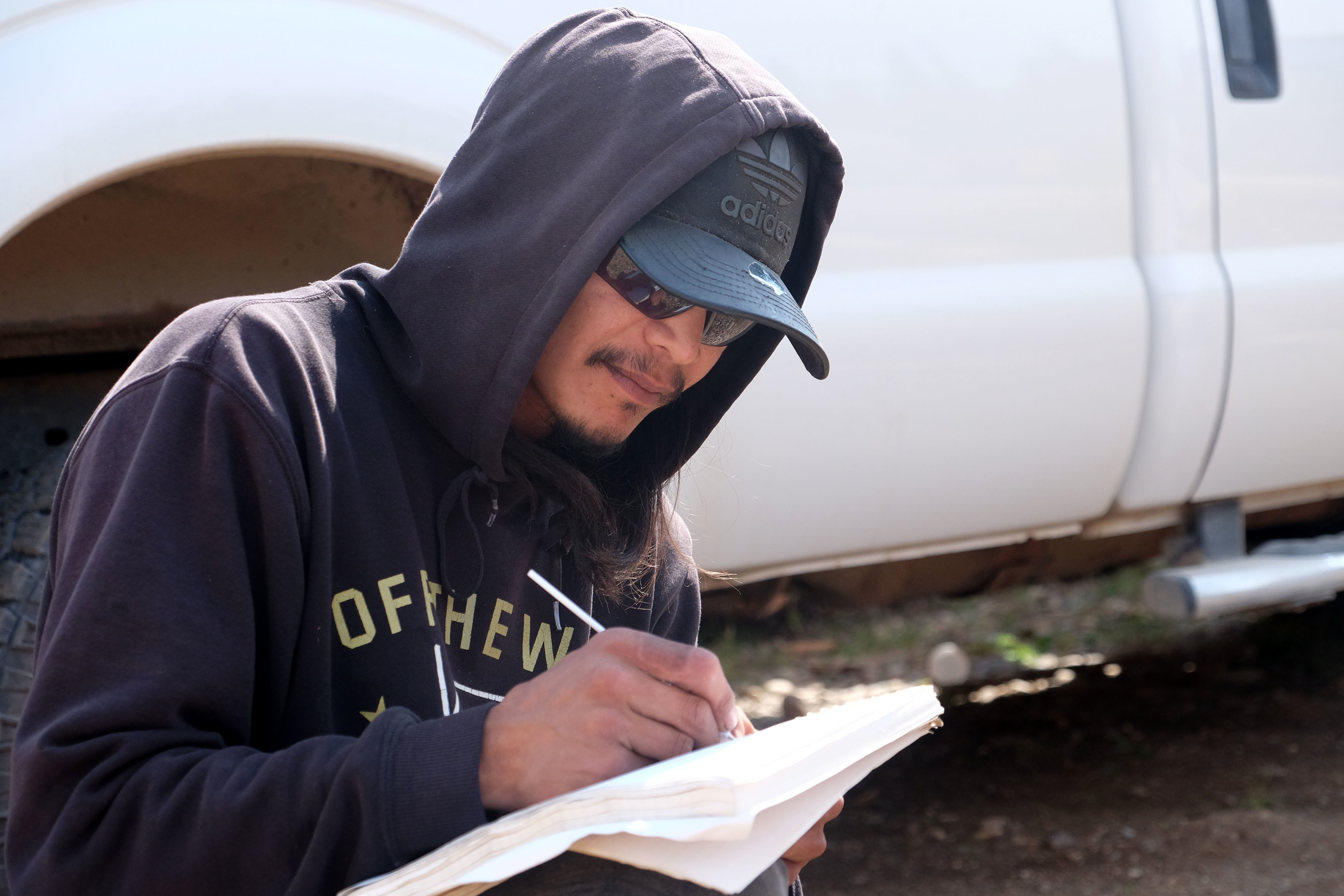

Roderick Kakfwi and his partner, Lori Ann Tobac, are on the waitlist for government housing, but they don't know when a house will become available. He's been getting by with odd jobs, but he can't afford to rent a home without government help, he said.

"We've lived with other people, but there, you don't feel at home. We want to have a place where we can call home."

After a few weeks of couch surfing with friends and family, Kakfwi decided to build a tent frame where they could stay for the summer.

"We've lived with other people, but there, you don't feel at home," he said. "We want to have a place where we can call home. This is going to do it."

Kakfwi's tent frame, which consists of a wooden structure covered by a tarp, is on his cousin Tommy Kakfwi's property. He's using borrowed materials and equipment to build the frame up. Once a spot on the housing list opens up, Tommy can use the structure as a garage.

"We're getting a lot of help; we're happy," Roderick Kakfwi said. "This should keep the rain off us. We're happy that we're getting here.

"It's just a place I want to call home. I just want to have a good place to sleep."

IV.

For the land corporation's Edwin Erutse, it's clear the housing crisis in Fort Good Hope is not going to end soon. There are too many people who need homes and not enough houses to fill the need. Come winter, people like Kakfwi and Cotchilly will still struggle to keep out the cold.

The work is slow going. Erutse says he's not sure when they'll have enough boards milled to actually start building homes.

The housing society is in contact with Heartland Timber Homes, a B.C.-based construction company that can provide designs and plans for their new lumber. One model, the Nahanni, requires 18,000 board feet of lumber for a three bedroom, 1,200 square-foot home.

Right now, Erutse wants people to learn how to use the mill correctly before adding more equipment such as industrial planers and drills.

"There isn't a grand plan," he said. "We're just grabbing the bull by the horns and taking it one step at a time."

In the longer term, the housing society plans to open up two homeless shelters, hopefully before winter.

"We're making small steps. We don't intend to solve the problem in the next year or two," Erutse said. "But as we move along, we can rely on our own people and come up with our own plans.

"We want to take care of our people. It's obvious to us the government is not going to take care of us if we don’t do it ourselves."