August 20, 2020

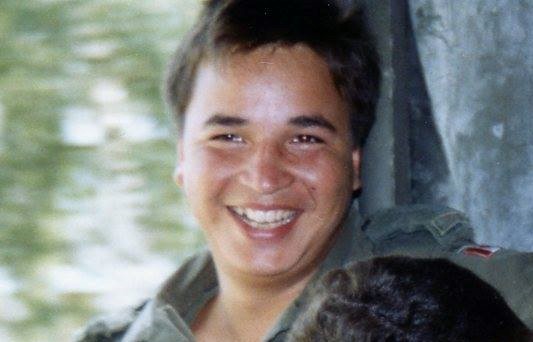

Aurel Dubé remembers the day he got the call from the Canadian Armed Forces that he’d be on the quick reaction force deployed to the Kanien'kehà:ka (Mohawk) community of Kanesatake during the summer of 1990.

It was already weeks into the siege that became known as the Oka Crisis, a conflict that stemmed over a contested area of land known as the Pines northwest of Montreal.

Dubé, a 26-year-old soldier with the Royal 22nd Regiment of the Canadian Army, was with family and friends in the Algonquin community of Kitigan Zibi, Que., when he got the call.

“My friends and family were saying ‘You’re not going to go to Oka are you?’ I had no choice but to say yes. This is my job, and I need to go do my job,” he said.

The decision caused a rift with his family for years, as well as a sense of guilt that lasted even longer.

“My family didn’t agree for me to go there and fight against my own people,” Dubé said.

“I will always remember the way my brothers reacted.”

The Oka Crisis was sparked by the expansion of a golf course on disputed land in Kanesatake. A group of people from the community had constructed a barricade on a small dirt road in March 1990 to halt further development and resistance continued after the Sûreté du Québec tried to enforce an injunction on July 11. An officer, Marcel Lemay, was killed during the raid.

The provincial police erected its own blockades and checkpoints on roads leading to Oka and Kanesatake, and after a month with no resolution Quebec Premier Robert Bourassa requested the help of the Canadian Armed Forces.

Members of the Royal 22nd Regiment replaced the Sûreté du Québec at barricades starting on Aug. 20, 1990.

It was called Operation Salon. A total of 4,500 Canadian Armed Forces members were involved, with about 3,700 members at its peak.

During the conflict, Kahnawake member and future Olympian Waneek Horn-Miller was stabbed by a soldier's bayonet. She was 14.

Dubé said that he lived with guilt over that until he had a chance to speak with her in 2016 at an event organized by the Armed Forces for Indigenous Awareness Week.

“I was crying because I felt guilty because I was there fighting against my own people,” he said.

“I told her that I want to apologize because I was there."

The events of 1990 had a profound impact not only on Dubé, but highlighted an internal conflict for other First Nations members of the Armed Forces who felt torn between their identity and their military service.

Rich military history

While exact numbers are elusive, Veterans Affairs Canada has estimated that as many as 12,000 First Nations, Métis and Inuit have served Canada in major conflicts of the 20th century. The Kanien'kehà:ka are no exception.

For a community like Kahnawake, 15 kilometres south of Montreal, the rich military history spans both sides of the Canada-United States border. Ray Deer, president of the Royal Canadian Legion Branch 219, served with the Royal Montreal Regiment and then later on joined the American military.

The deployment of the military to Deer’s home community, which had blocked the Honoré Mercier Bridge that connects the South Shore to the island of Montreal in solidarity with Kanesatake, changed his views forever.

“I was proud at the time of my military service. I always talked about being in the Canadian Forces. But when that occurred and they sent troops over here, I was really disappointed to the point where I didn’t even want to say anymore that I was in the Canadian Forces,” said Deer.

In 1990, Deer was stationed overseas in Germany with the American army and his request for leave was denied.

“I had always been there to defend whatever nation I was serving but now there’s a possibility that someone might take the life of a family member or a community member? It was a huge dilemma for me, what could I do?” said Deer.

He wanted to come home to help his community. Other veterans, especially those with combat experience, lent their expertise at the barricades and the Legion hall in Kahnawake became a headquarters for veterans, warriors, and civilians to exchange information throughout the siege.

Veterans stood in solidarity

Ellen Gabriel, an activist and artist from Kanesatake who is known for her involvement as a spokesperson during the Oka Crisis, said one elderly veteran of the Second World War “saved” her sanity.

“Relying on people like that to get you through the day was a gift because they’re able to take it moment by moment,” said Gabriel.

“There was always that looming dread over our heads on a daily basis but their courage and dignity was something that was inspiration and motivating. But, it also made us more defiant."

First Nations veterans from across the country also travelled to Kanesatake to show their solidarity. David O. Peltier, who served in Sicily during the Second World War, was among a group of veterans from Wikwemikong First Nation who travelled from Ontario to the Peace Camp established in Oka, Que., by Indigenous and non-Indigenous supporters.

“One of the reasons why they were veterans was to protect the country, and they felt they had that role still. From their perspective, it was appalling for them to see the army deployed against Indigenous people,” said Peltier’s daughter Doris Peltier.

Peliter said it was important for her father to show his support because of the way the Canadian government was treating Kanesatake.

“It was really an opportunity for them to stand in solidarity,” said Peltier.

Gabriel said the gesture meant a lot and lifted the spirits of many in Kanesatake.

“It’s hard to express in words how much it touched and moved me because they’re elders. It was such a crazy time here, and so dangerous and they came anyway,” said Gabriel.

Requests for an apology

For Tim O'Loan, a 54-year-old member of the Dene Nation and retired Canadian Armed Forces master corporal, the Oka Crisis had a profound impact on his military career.

“It planted the seed in which I ended up having to leave the military,” he said.

O'Loan joined the army right out of high school and during the summer of 1990 was stationed in Winnipeg. Soldiers had few qualms, he said, about sharing their feelings about Indigenous people.

“People were turning on me, and during the Oka Crisis that summer was a particularly dark time,” said O’Loan.

“For me, as a serving member, I was torn about my oath to the Crown yet here was the Crown turning against Indigenous people as a whole.”

He left the military in 1993 to pursue a degree in political science, and later joined the Truth and Reconciliation Commission as a special adviser to commission chair Justice Murray Sinclair.

Reflecting on the 30th anniversary of the Oka Crisis, he said he wants to see the relationship between the Canadian Armed Forces and Kanien'kehà:ka Nation repaired, and hopes to see an apology from the federal government “to put our 30-year wounded past behind us.”

“This country is lesser as a result of the Oka Crisis. If it is going to be a great country, not only do we need to deal with our uncomfortable truth with survivors but we need to move forward with a closer relationship between the Crown and Mohawk Nation.”

Minister backs apology request

Minister of Indigenous Services Marc Miller would also like to see an apology.

“It can’t be superficial where everyone just walks away after. In the last few years, there have been some really good programs in the Armed Forces, but much more work could be done,” he said.

After 1990, the Canadian military introduced Indigenous Awareness Week and created the Defence Aboriginal Advisory Group in 1995 to advise commanders on significant issues affecting the lives of Indigenous people working at the Department of National Defence and serving in the Canadian Armed Forces.

In recent years, more programs have also been created to develop relationships with Indigenous communities and increase awareness of military opportunities.

![Indigenous Services Minister Marc Miller listens to a question during a news conference in Ottawa, Aug. 12, 2020. (Adrian Wyld/Canadian Press]](https://newsinteractives.cbc.ca/craft-assets/images/CP18584474.JPG)

“There’s really some unfinished work. I’ve talked to the Minister of Defence about it because with those particular communities that is something that is still very acute and for people of that generation, very raw,” said Miller.

To commemorate the 30th anniversary, Miller, along with Minister of Crown-Indigenous Relations Carolyn Bennett, and Minister of Northern Affairs Daniel Vandal said in a statement that Canada “must resolve to never order the deployment of the Canadian Armed Forces against Indigenous People.”

Miller said sending the army into an Indigenous community in Canada was “abhorrent” given the level of military service from First Nations, Métis and Inuit.

One of those veterans — Joe Armstrong — died of a heart condition after a rock hit him in the chest in August 1990 when a convoy of women, children, and elders left Kahnawake in fear of a military invasion.

“The death of elder Armstrong is never really mentioned,” said Miller.

“Here is someone seeing people he defended throw rocks at him.”

Miller said the events that summer hit home for him in a number of ways. He was an army reservist from 1990 to 1994. During the Oka Crisis, he was at a Canadian Forces base located in the municipality of Saint-Gabriel-de-Valcartier, 15 kilometres northwest of Quebec City.

Four young men from Kahnawake, including Derek Montour, were in his platoon, and left abruptly to return home.

“One second we were in training, and the next second we were gone because we requested to come home,” said Montour, who is now the executive director of Kahnawake Shakotiia'takehnhas Community Services.

“While I was there, it was tough. You could hear some of the people you’ve potentially committed your life to [with] this force ... you’re hearing your buddies say ‘Damn, I wish we could go in and kill all them savages.’ These are the people you’re serving with, so it was a real eyeopener about perspective and racism.”

Montour never returned to the Canadian Reserve. By January 1991 he was off to boot camp with the United States Marine Corps where he served for a decade. Like Deer and O’Loan, the events of 1990 had a lasting impact on his career.

“I had always been interested in serving in the military. I still had that interest but not in the Canadian Army at that point,” said Montour.

“It showed who we are as a people and shaped how the rest of Canada perceives Kahnawake and Kanesatake and our willingness to stand for what we believe in. That degree of pride is important, and it still makes me conscious of my obligations to protect my family and my community.”