Thirty years ago, images of warriors clad in camouflage and bandanas, wielding guns and bright red-and-yellow flags were plastered across newspapers and television broadcasts throughout the Oka Crisis.

The 78-day standoff that began on July 11, 1990, between the Kanien'kehà:ka (Mohawk) community of Kanesatake, the Sûréte du Québec provincial police and, later, the Canadian military was over a contested area of land known as the Pines northwest of Montreal. In solidarity, the Kanien'kehà:ka community of Kahnawake blocked the Honoré Mercier Bridge that connects the South Shore to the island of Montreal.

The Kanien'kehà:ka and their fight for human rights was put on the Canadian and international stage that summer, and so was Karoniaktajeh Louis Hall’s warrior flag.

“The flag was zeroed-in on by the media,” said Teiowí:sonte Thomas Deer, communications co-ordinator for the Kanien'kehà:ka Nation Office in Kahnawake.

“News coverage of the crisis amplified the flag’s fame as not only an Indigenous symbol of unity but of resistance. From that point on, other Onkwehón:we [Indigenous] Peoples began using this flag as they resisted colonial oppression.”

Who was Karoniaktajeh Louis Hall?

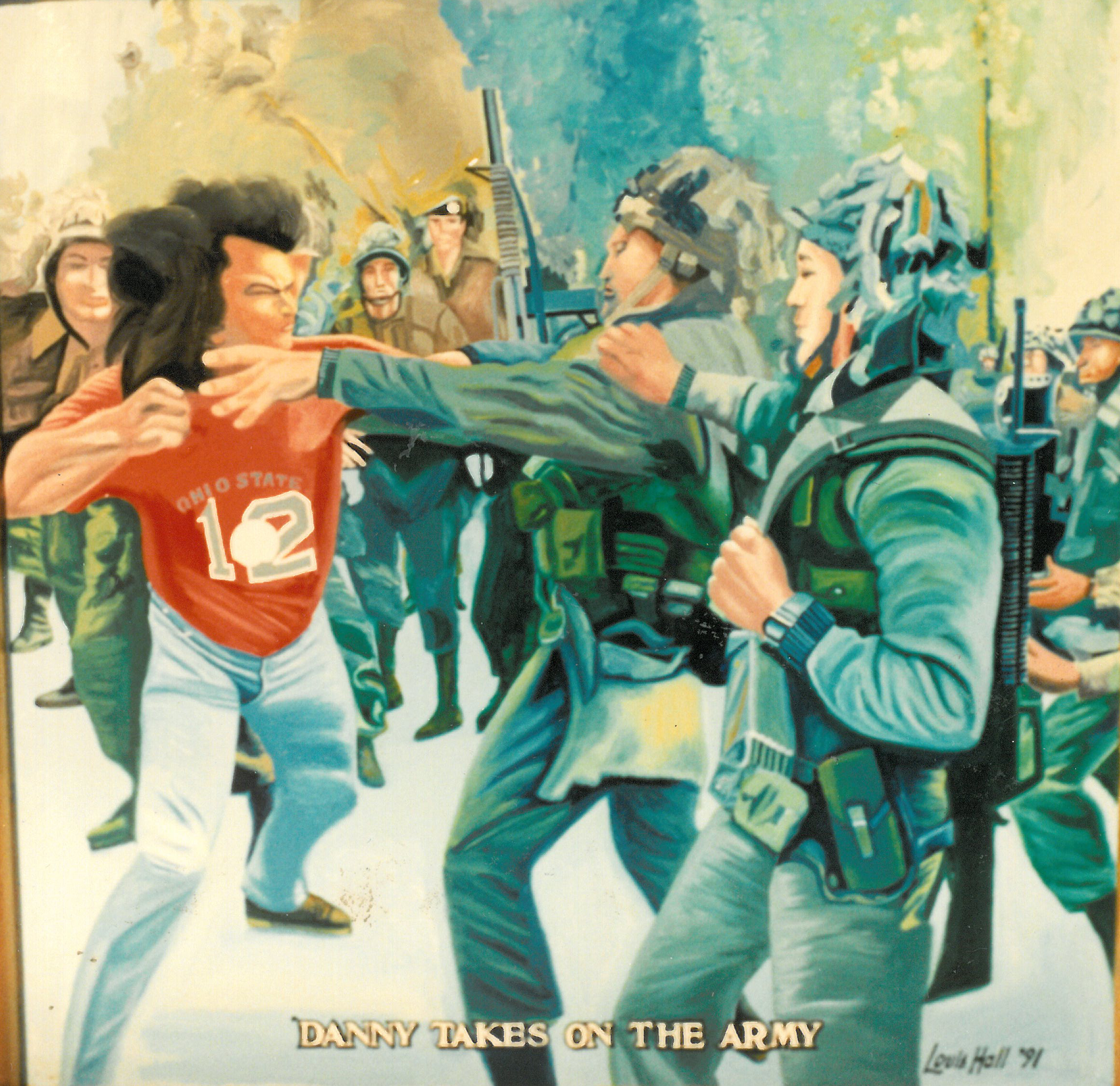

Hall, who died in 1993 at the age of 75, was an activist, writer and artist from Kahnawake. He first created the flag in 1974, when he and others went into the Adirondack Mountains to create a new settlement in upstate New York.

Dubbed the "unity flag" or "Indian flag," it depicted a long-haired Indigenous man over a sunburst atop a red banner, and was intended as a symbol for all Indigenous people to stand behind.

In the 1980s, Hall made a new version of the flag, replacing the long-haired man with a Kanien’kehá:ka warrior. It was designed specifically for the Rotisken’rakéhte, or Mohawk Warrior Society, serving as a symbol for the traditional vanguard of the Kanien’kehá:ka Nation when carrying out their duties for the people.

That version of the flag is the one most recognizable today; it has been mass produced on flags, clothing, key chains, stickers and decals.

“That was what he wanted,” said Louise Leclaire, Hall’s niece and closest surviving relative, about the flag being used everywhere.

“He loved his people, and he wanted to make sure Indians deserved their traditions, language, and just to have pride in who they are.”

An activation of pride

Kahente Horn-Miller, an associate professor at Carleton University in Ottawa and the school’s assistant vice-president of Indigenous initiatives, said the flag became an active part of Kanien’kehá:ka communicating their identity.

“What Karoniaktajeh was trying to do is activate that sense of pride in who we are,” she said.

In 2010, she published "From Paintings to Power," an academic article about the flag, in the Journal of the Society for Socialist Studies.

The flag is often misrepresented, she said. Negative connotations were placed on it because of how the Oka Crisis was covered in the media.

“The way we see it represented, it’s immediately associated with a violence — the English term 'warrior' — which has completely different connotations than what we describe our men and their role as, which is Rotisken’rakéhte, 'he carries the burden of peace,'” said Horn-Miller.

“The media at the time of the Oka Crisis created an image of the warrior to vilify our people and what we were doing, and that still continues. When we stand up for something, we’re vilified for it.”

Ellen Gabriel, an activist and artist from Kanesatake who is known for her involvement as spokesperson for the longhouse during the crisis, said she had mixed feelings about the flag for similar reasons.

“On one hand, I am proud because it is a symbol of the resistance of 1990," said Gabriel.

"But my experience of it first-hand in the community wasn’t so pleasant."

When the barricades came down, she said, she faced harassment from people bearing the flag. The images that were predominant in the news, she said, created a romanticized image of warriors and the flag’s association with “male machismo” ignored Kanien’kehá:ka women’s strong leadership role throughout the crisis.

“It’s sexy — a cute guy wearing a mask … holding an AK-47. It looks so exotic in Canada, right? But when the SWAT team arrived at 5:15 in the morning on July 11, it was the women that went to the front,” she said.

“There hasn’t been an in-depth discussion in our communities about that machismo and how it hurt a lot of us afterwards.”

A visual manifestation of the Great Law of Peace

What did Hall intend the warrior flag to mean? Horn-Miller describes the flag as a visual manifestation of the longhouse’s oral constitution, the Kaianera'kó:wa (Great Law of Peace).

“It’s about peace building, and at its root, when people fly that flag they get a sense of that but don’t fully understand that,” said Horn-Miller.

“That’s actually the beauty of the flag. Even though you don’t know where it comes from, it resonates with people.”

From coast to coast, the flag has been used by Indigenous Peoples across the country, and beyond. Mi’kmaq flew the flag during the lobster dispute at Esgenoôpetitj between 1999 and 2002; it was seen at rallies and round dances during Idle No More, during pipeline conflicts at Standing Rock, in Wet'suwet'en territory and even at Black Lives Matter protests in 2020.

“You can see that flag just about anywhere in the world where there is an Indigenous uprising or movement. I’ve seen that flag flying in New Zealand, Australia, South America, and I’ve seen it being flown in [the Palestinian territories],” said Kanesatake resident Clifton Nicholas.

“It’s an amazingly powerful symbol. It was pure genius to Louis Hall and what he created. It’s outgrown him.”

Legacy

The criticism following the Oka Crisis regarding women’s roles within Indigenous resistance and how they were not represented in the flag didn’t fall on deaf ears. Before Hall died, Deer and Horn-Miller said, another version of the flag was painted depicting a long-haired Indigenous man and woman.

“This final version of the flag was referred to as the Indigenous Flag of Unity and Resistance,” said Deer.

“Maybe at some point, that flag can become more prominent.”

Hall left his paintings and writings to the Warrior Society in Kahnawake in his will. For men like Deer and Nicholas, Hall’s legacy through art and writing continues to have long-lasting impacts three decades after his death.

“Karoniaktajeh was a true philosopher and made people believe,” said Deer, who is also a comic book artist and illustrator.

“[The year] 1990 led me to the longhouse, but Karoniaktajeh’s teachings kept me there. His artwork inspired me to pursue a career in art as well, and in a lot of ways I feel compelled to continue where he left off.”

Nicholas said he felt a sense of empowerment reading Hall’s writings as a teenager.

“He’s one of the people that I look up to. You may not agree with him, but he did shake up the world,” said Nicholas.

“The reason why I’m vocal is because of men like him that said it’s OK to be vocal.”