October 24, 2020

Listen to The Notorious NEP: a special three-part podcast.

Don Dickson can still remember walking into a car dealership in Calgary in 1974 to slap down what was then a small fortune in cash and buy a new car — a dark green LTD Landau, the sort of thing that would really catch the eye in a gritty '70s chase scene.

He could afford it.

Calgary was booming, people were pouring into the province to get their share of the black gold rush and Dickson was a newly minted real estate agent. It seemed like the good times would never end.

But booms always go bust.

Ask any Albertan about Pierre Elliot Trudeau and his federal Liberal Party at that time and you're likely to hear three letters at some point in the response: NEP, or National Energy Program for the uninitiated. It's something that doesn't really need an explanation for many in Alberta. It has become political shorthand for Eastern Canada taking advantage of the West.

The NEP was an effort by Ottawa to redistribute some of the oil wealth from Alberta and other producing provinces, while keeping prices low for Canadians across the country through a series of taxes and national price controls. Instead, it set the stage for a battle between political giants, led to the first upswing of western separatism and contributed to the cratering of a booming economy.

Many thousands lost their jobs and their homes and blamed the program.

The NEP, announced 40 years ago on Oct. 28, continues to exert a big influence in the province, acting as a sort of foundational myth of western alienation and self-determination.

The battles of the early '80s still resonate in the sometimes tense relationship between Alberta and Ottawa, particularly as the province once again convulses and petro-politics take centre stage with another Trudeau in office.

To understand what happened, it's worth going back to Dickson and his new ride.

The big boom

"I remember some of my first sales, that people had bought the house a year ago and then sold it for double the price within a year and a half. Like, talk about an investment," said Dickson, speaking recently about those boom times.

"I mean, it was just insane back then."

Dickson said his fancy new car was equipped with an eight-track, and he had a little tradition every time he sold a home, which happened often.

"I had only two or three eight tracks and one of them was Queen," he said.

"So I'd put that in there and we'd put in We are the Champions. And then when we walked into the office the next morning to turn in the sale, we'd say, 'Another one bites the dust.'"

Dickson wasn't the only one prospering. Newspapers at the time were crammed with help-wanted ads, energy companies were making big investments in the patch, skyscrapers were rising out of the prairie in Calgary and people were flocking to Alberta from all over the country. In the '70s, the province’s population exploded — almost doubling to more than two million people.

The boom was the product of global forces well beyond Alberta's borders that conspired to make the ground below incredibly valuable, but those same forces were taking a toll on the finances of others.

"My grandmother always used to say when someone is laughing, someone else is crying," said Paul Chastko, a senior instructor at the University of Calgary who specializes in the North American petroleum industry.

Global instability, soaring prices

In 1973, Egypt and Syria launched an attack on Israel, and Arab countries, through OPEC, started choking off oil supplies to Israel's allies, including the U.S.. Between Thanksgiving and New Year's Day, the price of oil went from $5.12 US per barrel to $11.65 and markets were thrown into chaos.

Within weeks, Americans were waiting in lineups at gas stations that stretched for blocks. It underlined North America's dependence on imported oil.

In response, U.S. President Richard Nixon announced a new energy policy aimed at self-sufficiency.

In Alberta, the money came rolling in. People in the province had the highest disposable incomes in the country.

As oil prices went up, however, so did inflation. Gasoline, heating homes, buying groceries — it all started to cost a lot more everywhere.

"As oil prices began to increase in the early 1970s, it was good news for Alberta, but it was bad news for consumers in central Canada, where the bulk of the Canadian economy, where the bulk of voters were," said Chastko.

By 1979, Iran's Islamic revolution wrestled control of that country, panicking markets and sending the price of oil soaring once again. Canada was considering rationing oil.

Pierre Trudeau was swept back into power in 1980 with a majority government, defeating the short-lived Conservative government of Alberta's own Joe Clark.

The pieces were in place.

Ottawa takes notice

The coming showdown over Alberta's oil wealth featured two political heavyweights who had very different ideas of what Confederation was all about.

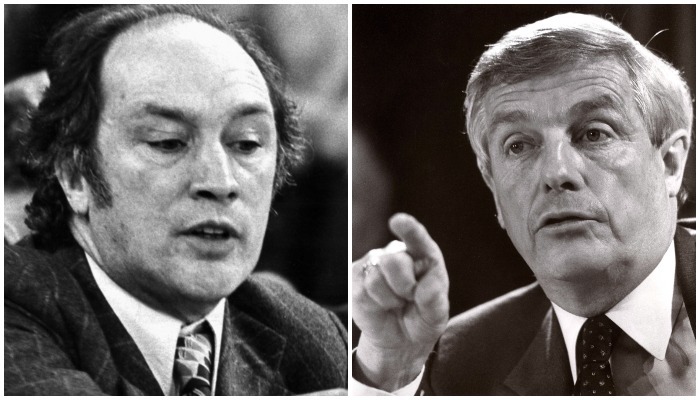

In one corner was Trudeau. His family history in Quebec stretched all the way back to the 1600s. He stared down separatists, slid down banisters and had a brown belt in judo.

In the other corner, the Progressive Conservative premier of Alberta, Peter Lougheed — a fourth-generation Albertan, a man whose legend is still evoked by both the NDP and the UCP in Alberta, and a former CFL running back whose Edmonton coach once described him as having “the guts of a burglar.”

Trudeau was busy warding off Quebec separatism and believed in a strong central government as a unifying force in Canada. Lougheed believed strong provinces, with control over their natural resources, would make a stronger federation.

"And so the battle was dividing this large fiscal pie — what Trudeau saw as a rebalancing of federal-provincial revenue, and what Lougheed thought was complete theft," said Duane Bratt, a political scientist at Mount Royal University in Calgary.

The federal Liberals figured Alberta was obliged to share its bounty with the rest of the country and help cushion the blow of rising inflation.

"The people in the West said, 'Hey, we should be able to get world market [prices] for our oil.' And Ottawa said, 'No, that would be unfair to other consumers.' It would — to the consumers in Central Canada — make for a huge redistribution of wealth from Central Canada to the West," said historian David Finch.

It didn't take long for the Liberals to act.

The NEP lands hard

It was October 1980 when the federal Liberals unveiled their new budget, which included the NEP. It landed hard in Alberta.

Federal Finance Minister Allan MacEachen promised the NEP would deliver energy security and Canadian ownership of resources, ideas that were popular with many Canadians.

"Taken together, the pricing and the expenditure measures will enhance Canada's energy security by reducing oil consumption and by 1990 ending our reliance on imported supplies," MacEachen said in the House of Commons.

But the Liberal government also had a $14.2 billion deficit and inflation raged at 10 per cent.

Alberta’s oil and gas wealth was irresistible.

"I expect energy to be a growing source of strength for the economy as a whole," said MacEachen.

The NEP was designed to inject cash into federal coffers, with a complicated bundle of taxes and regulations.

It included a new tax on natural gas exports, a "petroleum and gas revenue tax," and a made-in-Canada oil price that meant Alberta would continue to sell its oil to the rest of the country at a discount.

It also pushed for more Canadian ownership in the patch, largely through Petro-Canada and a lot of it through grants for Canadian companies to explore for oil and gas that were targeted to areas outside Alberta.

Marc Lalonde, the energy minister and the architect of the NEP, insisted at the time that it was a fair compromise with western provinces.

"I think it will be recognized as being indeed very fair. This will still leave the producing provinces in the west with the largest share of revenues and larger than in any state or any other province in any other country in the world," he said.

"And we've walked many extra miles to accommodate them. We've abandoned several of the proposals we have made in order to accommodate them. I don't think it's fair to ask for more."

But internal cabinet documents, cited by historian Tammy Nemeth in her chapter of the book Alberta Formed Alberta Transformed, suggest something different was happening behind the scenes.

"The energy proposals as they now stand, would be seen by many to be the biggest revenue grab in the history of the country," reads a memorandum written by the deputy minister of finance and his colleagues in the months before the NEP was announced.

"The energy mines and resources tax and pricing measures would allow eastern oil and gas consumers to continue enjoying massive rents via lower prices and the federal treasury to collect billions from a gas export tax, both of which would reinforce western alienation."

They knew Alberta wouldn't accept the NEP. This was high stakes political gamesmanship. And it was not going over well in the West.

Alberta pushes back

As the new policies were being announced, 27-year-old Jim Dinning was watching from a room in the Alberta legislature.

At the time, he was the chief of staff to the Alberta finance minister, but he would in later years take the reins of finance minister under Premier Ralph Klein.

"I just remember being a staffer in the building, and I think all of us were together in the cabinet room watching Mr. MacEachen deliver the bad news, which was really a kick in the ass to Alberta … and the steam was just coming out of ears around the table," he said.

But it was more than just a financial hit, or the sense that the federal government was overstepping its constitutional bounds and meddling with Alberta's resources. It was a shot of adrenalin right into the restless heart of western alienation.

"It just pissed off so many western Canadians who felt once again confirmed that we were second-class citizens," said Dinning.

What wasn't known, as he sat around that table with his colleagues, was how his ultimate boss, the premier, would respond.

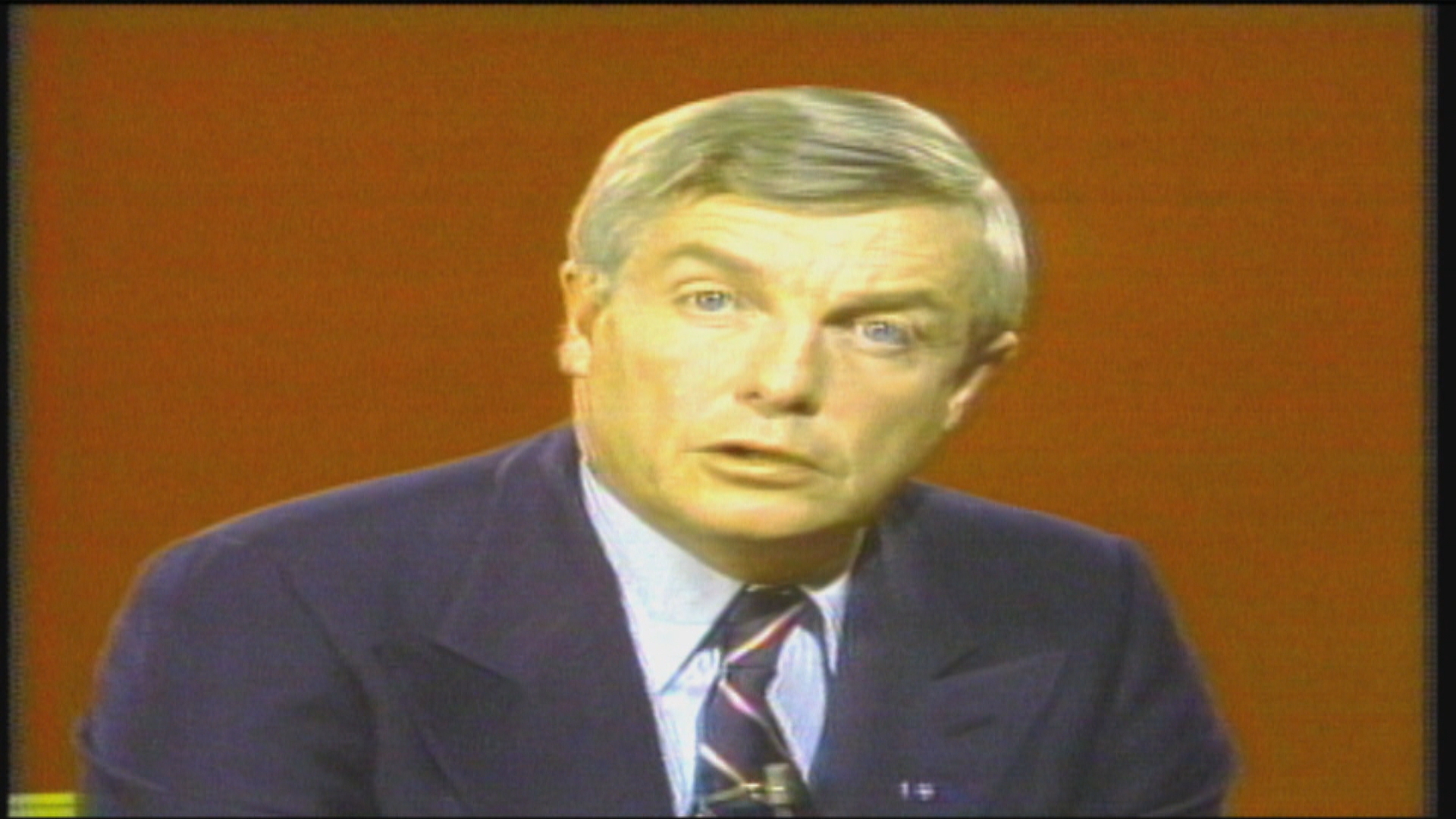

Forty-eight hours after the program was announced, Lougheed broadcast his reaction on TV.

Sitting forward on a yellow chair, wearing a dark blue suit and striped tie, the Alberta premier fixed the camera with the look of a man who's about to make a bold but well-calculated wager.

After staking out his position and arguing that if the resources were based in Ontario, every Canadian would be paying the world price of oil, Lougheed announced his plan of action.

"So we've decided to recommend to the legislature that we should reduce the rate in which we're producing our oil to about 85 per cent of its capacity."

Alberta would turn down the taps by 15 per cent, choking off supply to the rest of the country, even though it would hurt the province’s bottom line.

It would cut supply by tens of thousands of barrels a day and force Canadians to turn to higher priced imports. Instead of paying for $17 a barrel for Alberta oil, they would have to fork out $40 a barrel for imports.

Along with the production cuts, Lougheed took other measures.

He announced the province was suspending the approval of new oilsands projects and would launch a legal challenge over the natural gas tax on the grounds that it violated the Constitution.

"Lougheed was too smart a lawyer to see the NEP for anything other than what it was. It was the federal government's opening position," said Chastko, the petroleum historian.

"It was an invitation to negotiate, and to be sure it was an iron fist in a velvet glove. But Peter Lougheed … he was not above putting his own iron fist in a velvet glove."

Joe Lougheed says his father knew his strategy was controversial, but felt he needed to make a stand.

"For him, I think it was a slippery slope," Joe Lougheed said in a recent interview. "If the federal government thinks they can intervene in provincial jurisdiction here, they can do it again and they can do it again and they can do it again."

When he made the announcement, the elder Lougheed urged Albertans not to waiver.

"Yes, we're going to have a storm in this province, but I think we've got enough strength and resolve to weather that storm."

His optimism was about to be tested, particularly as money started to flee the corporate towers of Calgary.

The patch reacts

Jim Gray is an industry titan in Alberta, and a geologist by training. He's been in the oil and gas exploration business since the mid-'50s.

When the NEP was brought in, Gray and his partner were building their own exploration company called Canadian Hunter Exploration Limited, which had started out in the early '70s with one desk and two Ford Pintos.

It didn’t take long for them to strike it big.

In the Grande Prairie area, next to the Rockies, they discovered the Elmworth natural gas field — one of the largest in the country.

"We were just determined to build a great big Canadian company," said Gray.

In 1980, Gray and his partner were preparing to expand their exploration program and they were focused on Canada, and Elmworth.

"We were getting ready with a budget of 100 million bucks, I can remember the number, which was a lot of money," he said.

But when the National Energy Program was introduced, they changed their plans.

"And so all we did was redefine our budgets. We spent more in the U.S. and substantially less in Canada," he said.

"I didn't feel very good at all. I was upset."

For Gray, there was a bitter irony — the federal government’s attempts to secure supply and Canadianize the industry were having the opposite effect.

He said Lougheed had a big fight on his hands, going up against the federal government and, potentially, the broader Canadian public.

"I mean, Saskatchewan and B.C. were kind of behind him," said Gray.

"But there was a lot of anger. And when we cut back on the oil production, there was a lot of support for that. We didn't object to that. I mean, we had to play the big game, the long game."

Both Alberta and Ottawa were playing to win.

Alberta turned down the taps in March of 1981, then again in June. To pay for the cost of increased imports, Ottawa brought in a special tax on gasoline that Lalonde called the "Lougheed levy."

All the while, rigs that would have been drilling in Alberta started heading south to the U.S.

Trudeau was defiant, however, and took on his critics — and an industry that he accused of nothing but self-interest — during a visit to Brandon, Man., in February 1981.

He said the program had been attacked by the provinces, but also the oil companies, the chairman of the Royal Bank, the "financial press" and the "editorial writers of our large newspaper chains." A sure sign, he said, that his government was doing the right thing.

"In any case, there certainly appears to be a large number of economic interests trying to wrap themselves in the flag of western pride, because let's look at the facts. Who gains by a rapid escalation to world price and who is hurt? The treasuries of the producing provinces certainly benefit, and the profits of the multinationals would be even more improved. But as the people like yourselves, the farmers, the small businessmen of Manitoba who would take it on the nose, he would deny."

Wrapped in the flag of western pride or not, oil and gas companies were moving their equipment and capital elsewhere, and anger, along with unemployment, was rising in the West.

Anger overflows

In November of 1980, not long after the NEP was introduced in Ottawa, a crowd of 2,700 people gathered at the Jubilee Auditorium in Edmonton to hear the leader of the Western Canada Concept Party speak.

A big banner on the stage read "Free the West."

The WCC was a separatist party led by B.C. lawyer Doug Christie, who would later gain fame — or infamy — defending neo-Nazis and Holocaust deniers in court.

"I have a feeling this is a moment in history tonight. We are waking up," he said that night in November.

Christie told the crowd that Central Canada was raping and plundering the West, with the federal Liberals thinking only about Quebec.

"They have to beg to Quebec, "Please vote for us.' I'm tired of begging. No more begging, please."

Also there that night was Alberta Liberal Nick Taylor, the only other political leader in the seething crowd.

"There was a pit between myself and the, I guess, orchestra pit between the stage and the audience. They kept running up to the end of the pit and spitting at me and throwing paper and stuff," he recalls.

"And they were really just foaming mad."

Taylor managed to make it out of the building that night, despite turning down the offer of a security escort.

"I was quite relieved when I got to the front door."

A member of the Western Canada Concept party did get elected in a provincial byelection in 1982, but it was short-lived — the candidate lost his seat months later in the general election.

The separatist movement petered out, but the anger and frustration in Alberta did not.

After almost a decade of prosperity, the province was on the downslide and the pain was being felt in Alberta's oil towns.

The capital that fled Alberta in the wake of the NEP was soon multiplied by a global recession that wreaked havoc across the western world. Crude prices started to fall as OPEC nations debated what to do about a glut of oil on the market.

There were 550 active drilling rigs in western Canada in 1980. Two years later, there were only 120.

By the end of 1982, Canada's unemployment rate was 13 per cent and Alberta's was more than 10 per cent.

People were no longer flocking to Alberta by the thousands. In fact, they were leaving.

In 1983, Alberta’s population shrunk for the first time since the Second World War.

An NEP compromise reached between Ottawa and Alberta two years before that contraction — which rejigged energy sharing quotas, removed the export tax on Alberta gas and eventually overturned a tax on wells — wasn't enough to staunch the inevitable flow and the story of the program that killed Alberta was set in hearts and minds across the province.

And even though the program has achieved the status of an unshakeable myth, there's also more than a little truth to the fact that it hurt.

The compromise and the damage done

Lalonde, the man who was the architect of the NEP, wishes people would move on.

"Stop bitching about the National Energy Program," he said. "This is 2020."

Lalonde said, knowing what he did when the program was developed, he would do the exact same thing again — not quite taking the bait on whether hindsight has given him second thoughts. Although he does say he might have pushed for more time to negotiate.

"I feel that the energy program became a kind of, should I say, a whipping boy … for a much broader problem, which was the radical change in the evolution of oil prices compared to what was expected by everybody," said Lalonde.

"Governments and the oil industry, everybody got caught with their pants down when the price of oil started going down rather than going up."

How much of that was caused by the NEP? Could the impact of the NEP be disentangled from the effects of the recession?

Robert Mansell wanted to know the answer to those questions. He’s an economist, and in the early '80s, he was teaching at the University of Calgary.

"I paid a lot of attention to what was happening. And so you would see all the data coming in. And yeah, it was a very interesting time, a very sad time," he said.

Factors like high interest rates and household debt certainly added to Alberta’s economic pain. The province would not have come out of a global recession unscathed.

But.

"Had there not been a National Energy Program, Alberta would have done much, much better, much better," said Mansell.

His number crunching shows that between 1980 and 1985 — thanks to a combination of federal taxes and price controls — the NEP siphoned roughly $100 billion out of the province.

"The NEP is the largest inter-regional transfer in Canadian history. You can't dispute those facts. So you might say, well, I intended good things to happen. But in the end, you have to be responsible for what actually happened, not what your intention was."

The flip side of that, however, are the global forces and the national responses to them that also contributed to a crippling situation in Alberta that still scars many an older citizen.

You remember realtor Don Dickson and his fancy new car?

"Well, the market just kind of fell apart," he said.

"And they just seemed to think the only way out of this whole mess was to jack interest rates up, you know, to hit a prime rate of 18 per cent. Like, oh, my God, who the hell can afford that?"

Many Albertans had large mortgages.

When housing prices plunged, they were under water — the mortgage was worth more than the value of the house.

"And then you had people that were going into foreclosure, just doing quit claims on their houses, where they just went into the bank, handed them the key. Thanks. See you later. And that was the end of that."

Some didn't even bother travelling to the bank and stuffed the keys in an envelope and shoved them in a post box. It was called "jingle mail."

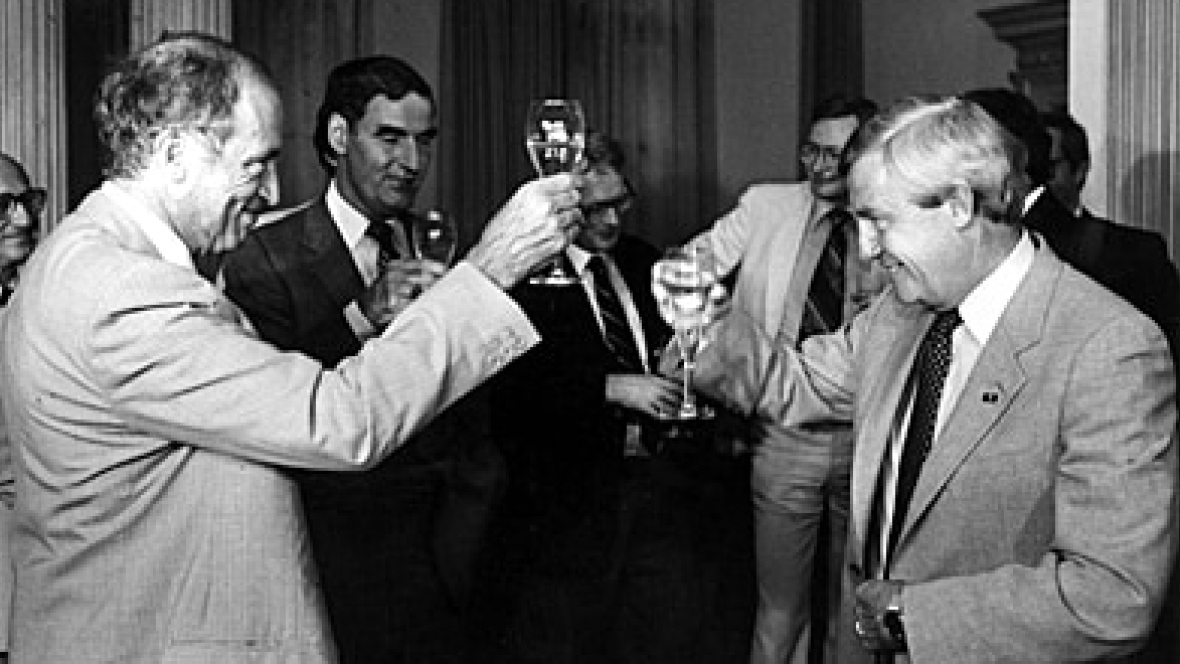

Lougheed, the legend who had stood up to Ottawa, regretted overselling his compromise with the feds, and he suffered the consequences.

He was the man who toasted the deal with Trudeau by clinking champagne glasses — a photograph of which was one of his biggest regrets — while the province headed into a tailspin.

Albertans still feel the vertigo.

Mythology set in stone

"I don't discount that many people blame the NEP for lost jobs, for lost incomes or lost prosperity," said petroleum historian Chastko.

"That's something that you can never, you can never explain away. And that it shouldn't be explained away as being done for the greater good. I just … to deal with the emotional and political baggage of the NEP is greater than the problems that the NEP itself created.”

Even Lougheed, a political figure whose shadow looms large in Alberta, fell victim to the anger and resentment brought on by the NEP. No thanks to that champagne-clinking photo.

To get that deal, Lougheed had turned down the taps, and forced the federal Liberals to back down from the harshest aspects of the NEP.

But a champagne toast didn't reflect the mood of the province, and in the end, when all the battles over NEP had been fought, it was the feeling that remained.

By 1984, the crowd at the Canada Cup hockey tournament final in Edmonton were booing Lougheed.

"I think that was an expression of the frustration that many Albertans felt, of the promises of the 1970s not being lived up to by the mid 1980s," said Chastko.

Trudeau left office in 1984 and Brian Mulroney's Progressive Conservatives took power in September of that year. The next year, the NEP was officially dead.

"Beginning on June 1st, 1985, we will let buyers be buyers and sellers be sellers," said Energy Minister Pat Carney in the House.

Lougheed retired as premier and leader of the Progressive Conservative Party a few months later.

The wounds from that time left a lasting mark on the province, and on the industry to which it is so closely tied. There was a new sense of vulnerability and a new shell of defiance against the powers out east, neither of which would fade.

The anger morphed into political action and the rise of Reform and, eventually, the new Conservative Party of Canada. The sense of betrayal is quick to resurface whenever Ottawa turns its regulatory gaze out west.

With the province once again convulsing amidst a new round of petro-politics and another global recession, the early days of the '80s look more and more familiar.

And as for Dickson? Well, he had to sell that car long ago.

"I remember I had to sell that car because it had a 460-cubic-inch engine and got like four miles to the gallon, so it was expensive," he said with a laugh. "Holy moly."