The Calgary Flames were battling the Anaheim Ducks at the Saddledome on May 5, 2015, when during a break in the game, the announcer informed the crowd of the provincial election result: The underdog NDP had just ended 43 years of Progressive Conservative reign.

There was little reaction from the crowd, perhaps more disbelief than either celebration or disappointment. After the game, reality began to sink in. Alberta was about to go in a new direction; the oil and gas sector braced itself.

It would have been hard that May evening in 2015 to guess at the sheer amount of change that Notley would bring to almost every part of the energy industry.

The NDP had campaigned on raising corporate taxes, reviewing how much in royalties the province should collect from industry and encouraging more refining in the province, among other promises.

The business world hates uncertainty and the NDP win had the oilpatch feeling baffled and rattled.

Overnight, the oilpatch had lost a generation of political contacts in government. The Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers didn’t even meet with the NDP until late in the election campaign.

Immediately after her victory, Notley cautioned the energy industry would be “A-OK,” but the sector definitely had its doubts.

"As an investor in the oilpatch, you're going to get your teeth kicked in," said Rafi Tahmazian with Canoe Financial, in an interview with CBC News shortly after leaving the game that night.

Over the past four years, her government has committed billions to diversify the energy sector and relieve pipeline bottlenecks through rail. She's broadened the carbon tax. The premier has also become an advocate for the sector on the national stage.

And many of Notley’s actions have resulted in a tremendous amount of interference in the market. With nearly every one of her government’s policies, there is a question of how they divide the oilpatch with either winners and losers or clear supporters and critics.

Canoe Financial's Rafi Tahmazian gives Rachel Notley a failing grade.

Structural changes in oil sector

Before examining each of the NDP’s major policy changes affecting the energy sector, it’s worth understanding how the sector has fared since the dramatic oil price crash of 2014.

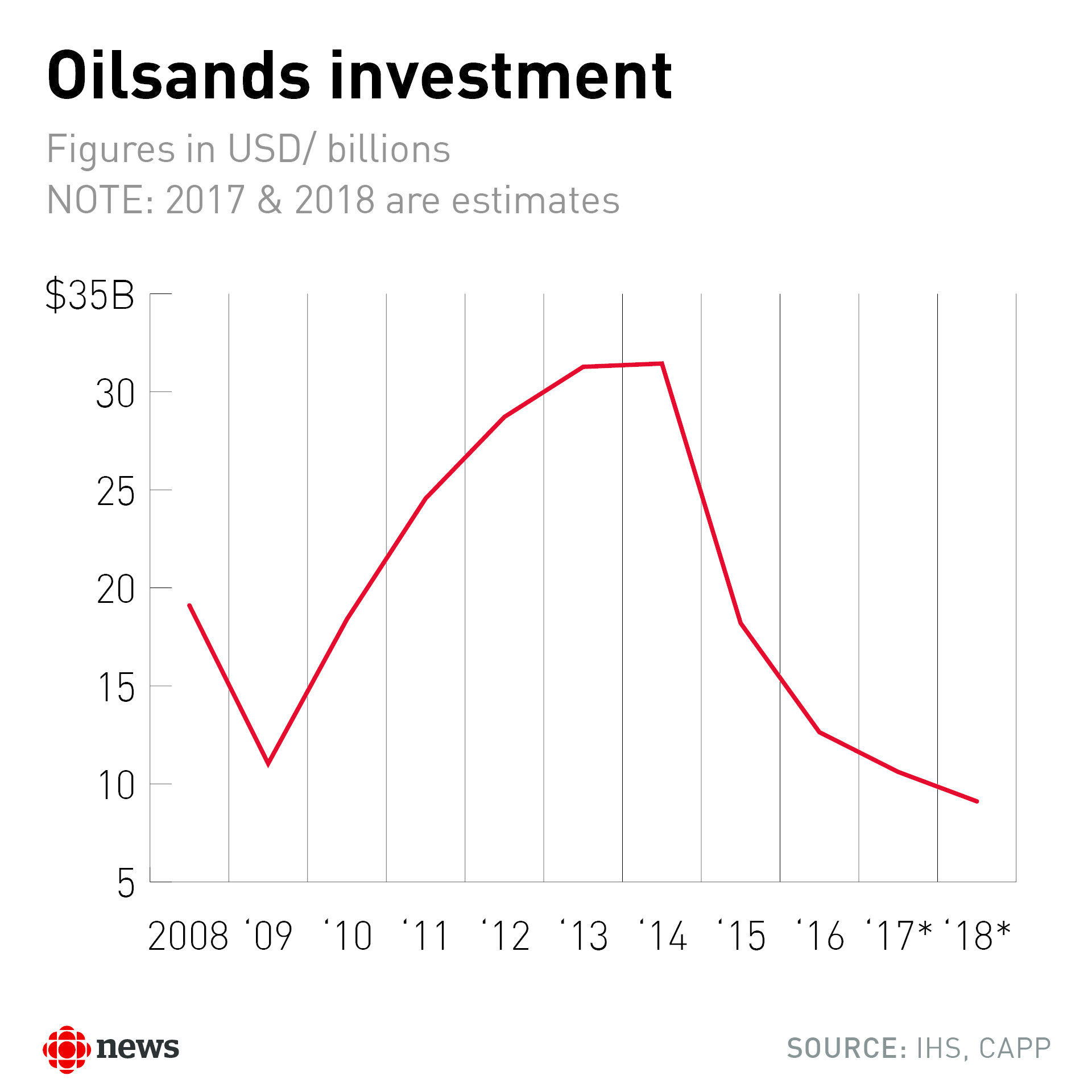

Over the last four years, oil production has continued to climb in Alberta. The oilsands have grown, although construction of new projects has slowed.

Several foreign companies have left the oilsands or drastically reduced their ownership stake in the Fort McMurray region. The reasons are varied.

The oilsands are typically a high-cost venture and take a long time to turn a profit. They were a popular investment in times of $100 US crude and quickly growing demand, but are less so in times of low prices and growing supply.

With global concerns about climate change, many companies are also shifting their focus away from higher emission operations to lower polluting ventures. Royal Dutch Shell, for instance, sold much of its oilsands assets, but is the key player behind the $40-billion Cdn LNG Canada project to ship natural gas to the West Coast and export it as liquified natural gas.

Notley and the NDP haven’t had much help on the energy file.

Successive federal governments have stumbled in their attempts to ensure new export pipelines are constructed in Western Canada. Even U.S. President Donald Trump hasn’t been able to get Keystone XL built, despite his fondness for the project.

Meanwhile, oil prices have only marginally improved since 2014. Pipeline constraints, coupled with increased supply, have led to several price crashes in Alberta as oil backlogs form within the province.

Lacklustre oil and gas prices are difficult to overcome, no matter how much a government spends or what actions it takes.

“There's no convincing analysis I've seen that leads to any kind of credible conclusion that policy over the last four years mattered anywhere near as much as the drop in oil prices," said Trevor Tombe, an economist with the University of Calgary.

Royalty review

As promised during the election campaign, the NDP ordered a review of how much the government collects from oil and gas companies.

Some Albertans felt the government wasn’t getting enough revenue from natural resources.

Industry was fearful of the result of this review. The new government was thought to be hostile towards oil and gas.

However, even during the consultation process, companies were left with a positive feeling.

Eight months after the election, the review was over and the consensus was the oilpatch had won the day. The review panel had updated the way government collects royalties from companies to keep in mind changing technology and trends in the sector.

"I think there was a lot of alarm at the outset of this process," said Gary Leach. At the time, he was the executive director of the Explorers and Producers Association of Canada, which represents small and mid-sized oil and gas companies.

"As the government has immersed itself in this subject and as the realities of governing the province have illuminated the subject, I think we became more confident."

This was the first large policy decision by the NDP and, while the oilpatch loathed another royalty review, this provided an opportunity to see if this government would be a friend or a foe.

While the whole process had created uncertainty for industry, the sector walked away pretty happy with the result.

Corporate taxes

Raising corporate taxes formed a cornerstone of the NDP’s economic plan in 2015, and also provided the basis of one of the key moments in the campaign: Progressive Conservative Leader Jim Prentice took criticism for seeming patronizing after challenging Notley's plan with the statement “I know that math is difficult” during a pivotal TV election debate.

The NDP pledged on the campaign trail to raise corporate taxes to 12 per cent, from 10 per cent, if the party formed the next government. It made good on the promise soon after.

Its argument was a hike in corporate taxes — combined with the elimination of the flat personal tax — would create a more stable and reliable revenue base for Alberta.

And the public appeared onside. After all, the Tory government’s own survey in 2015 showed more than two-thirds of Albertans also wanted to see corporations pay more.

Yet critics warned the tax boost would erode Alberta’s competitiveness and harm energy companies already struggling to pay the bills. It would also kill jobs, they argued.

So what happened?

When trying to assess the policy, it turns out that math is, if not difficult, at least very complex.

Jobs evaporated, but not for any single reason. Weak commodity prices, pipeline bottlenecks and advances in technology all contributed to the layoffs.

“It is very hard to … tease out the effect of a particular policy change from the hundreds or thousands of other things going on in the economy,” said University of Calgary economist Trevor Tombe.

“We can't simply point to the large drop in investments in Alberta — which is undeniable — but most of that is almost surely due to lower oil prices and lower investment in expanding oilsands facilities, for example. So it wouldn't be fair to link the corporate income tax increase to that drop in investment.”

Still, many in the oilpatch say Alberta has surrendered its competitive edge, especially when compared to the United States, which has slashed federal taxes and regulation.

“We've seen other jurisdictions that compete for capital [investment] move in the complete opposite direction from a tax perspective,” said Ben Brunnen of CAPP.

CAPP is calling for corporate taxes to be cut to 10 per cent. United Conservative Leader Jason Kenney has pledged to cut corporate taxes to eight per cent.

Alberta Finance Minister Joe Ceci says in the big picture, Alberta is well positioned

“You look across the country, we have among the lowest in the country for corporate taxes,” he said. “In addition, we have no sales tax, no payroll tax and no health premiums.”

Meanwhile, the corporate tax hike didn’t see provincial revenues surge.

Revenue from corporate income tax dropped each year, from $4.2 billion in 2015-16 to $3.4 billion in 2017-18. This year, however, the government believes those revenues will climb to $4.1 billion.

Ceci believes the decrease was due to the “prolonged and significant” drop in the price of oil.

'Math is difficult': PC leader Jim Prentice and NDP leader Rachel Notley battle it out during an election debate in 2015.

Curtailment

The government’s decision to place mandatory production cuts on Alberta’s oil industry was historic and controversial, but made with the backing of key oil companies as well as United Conservative Party Leader Jason Kenney.

It was, in the premier’s opinion, a decisive response to an extraordinary situation.

Pipeline bottlenecks and rising oilsands production were already weighing on Canadian crude prices when several U.S. refineries went offline for maintenance in the fall of 2018.

This “perfect storm” led to a massive glut of Canadian crude and a widening gulf between the price of Western Canadian Select (WCS) and West Texas Intermediate (WTI), the U.S. benchmark contract.

The price gap — typically around $15 US a barrel — ballooned to over $50 US a barrel in October. In economic terms, it meant foregone royalties, taxes and economic activity.

Cenovus Energy and Canadian Natural Resources, both key oilsands players, were among those pushing for Rachel Notley to impose temporary cuts to rectify the problem.

Canada’s three major integrated companies — Suncor, Husky Energy and Imperial Oil — disagreed. They said the market was working, pointing out companies were already curtailing production voluntarily, and warning that interfering in the free market would have both economic and trade risks.

In early December, the province announced Alberta would curtail oil production for the first time since Peter Lougheed did it in his fight with Ottawa over the National Energy Program three decades earlier.

The 8.7-per-cent cut in crude output, which went into effect on Jan. 1, quickly lifted the price of WCS oil, closing the gulf with WTI to under $10 US a barrel.

"We've seen the market respond quite definitively to the actions that we took," Notley told reporters just two weeks into the strategy as prices climbed.

But criticism of the decision has continued, whether it’s affecting the economics of the crude-by-rail market or long-term worries about its impact on the investment climate.

"That's a permanent uncertainty that the government has created by stepping in with this curtailment," David Goldwyn, an assistant secretary of energy for international affairs under U.S. President Bill Clinton, told CBC News earlier this year.

He said the Alberta government's decision to intervene in the market would lead some oil companies to wonder when it will take such action again. It's the kind of intervention that makes some investors wary.

"It's probably, in the long run, going to be an unfortunate step for the Alberta oil sector," Goldwyn said.

Alberta has ratcheted down the curtailment each month since the policy was implemented.

In a further bid to address the oil glut, the government also announced a $3.7-billion strategy to move up to 120,000 barrels per day of crude by railcar by mid-2020.

Though it drew fire from the UCP, the strategy could get a warmer welcome since Enbridge announced its Line 3 pipeline replacement project from Alberta to Wisconsin is delayed to the second half of 2020, from the end of 2019, while the project awaits the required permits.

Ultimately, the full impact of the government’s curtailment policy is something that may take some time to completely shake out.

“I think it'll probably be the better part of a year until we can really kind of look back and then kind of say, you know, was it worth it,” said Scotiabank analyst Rory Johnston.

Refining and upgrading

One of the older planks in the NDP’s election platform was to process more of Alberta’s oil and natural gas inside the province before shipping it down the line.

The NDP believes that if the province can do more refining, upgrading and processing of its energy resources at home, then Alberta can get more value from those resources, diversify its options and create more jobs.

So far, the NDP’s “Made-in-Alberta” strategy has committed more than $3 billion in support for energy diversification, whether in the form of royalty credits, loan guarantees or grants.

It includes up to $1 billion in financial incentives to encourage companies to build two to five bitumen upgrading facilities. In January, Alberta signed a letter of intent to provide a $440-million loan guarantee towards construction of a $2-billion facility by Calgary-based Value Creation Inc.

Another $2.1 billion has been earmarked for the petrochemical sector to produce plastics used in everything from chairs, piping, medical equipment and rugs, and the sector is expected to grow substantially in the future.

The government says its plan is to unlock $12.6 billion in private sector investment.

Calgary-based Inter Pipeline's $3.5-billion Heartland Petrochemical Complex in Strathcona County was one of the first projects to receive assistance under the first round of the province's Petrochemicals Diversification Program.

"Canada doesn't produce any polypropylene, but we import about $1 billion a year ... so we're going to change that," said David Chappell, senior vice-president of petrochemical development for Inter Pipeline, told CBC News last year.

"And that's important for Canada, to become less hewers of wood and drawers of water. Now, we'll actually add value.”

Energy consultancy Wood Mackenzie said last year that these sorts of incentives for the petrochemical sector should help Alberta compete more quickly with the U.S.

But for those who believe the government needs to get out of the business of being in business, to paraphrase late premier Ralph Klein, these sorts of subsidies don’t sit well. Some don’t like the idea of putting public dollars at risk. Others don’t like government picking winners and losers.

Environmental groups have also targeted the NDP, claiming Alberta subsidies to the fossil fuel sector have grown and surpassed $2 billion in the last fiscal year.

Notley’s announcement in December that the government wanted to hear expressions of interest in building a refinery in the province was also met with skepticism.

Experts say Alberta already has more refinery capacity than it needs and the biggest problem facing the province's oilpatch remains unsolved — a lack of export pipeline space.

Carbon tax

One of the most remarkable images of the last four years in Alberta is the photo taken on a Sunday afternoon in Edmonton with the NDP flanked by environmental leaders, Indigenous chiefs, and the CEOs of four of the largest oil companies in the country. They were all on stage together and smiling as Notley announced a climate plan.

It was arguably the biggest policy move of her term and the centrepiece of the policy is a carbon tax.

Based on the announcement, it appeared the oilpatch was unified in its support, but in the days to follow some industry groups were on the fence and some companies, like Imperial Oil, began to express concern.

Alberta has had a carbon tax on its largest emitters for several years, but this carbon tax was more robust and covered just about everybody, from the largest oilsands company to the average person gassing up their car.

The reason for the discord in the oilpatch was how the policy is structured, specifically the way it incentivized companies to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The oilsands companies with lower emissions actually earn money from the program, while the least efficient facilities could pay several dollars per barrel of oil. Critics say that the provincial government is picking winners and losers instead of taxing all the companies at the same rate.

Suncor CEO Steve Williams has endorsed the idea of a carbon tax for several years as long as it is revenue-neutral and some of the cash is recycled back into the industry for innovation.

"We think climate change is happening," said Williams to journalists several months before the NDP unveiled the policy in Alberta. "We think a broad-based carbon price is the right answer.”

Others, say the policy has deterred investment in the oilpatch.

“All you've done is saddled companies with incremental costs,” said Robert Cooper, a vice-president at Calgary-based investment firm Acumen Capital Partners.

He said the carbon tax and other policies of the NDP demonstrate their “economic ineptitude.”

"It's been a disaster,” he said of the NDP government. “There's been all sorts of policy that has been implemented since 2015 that has just thrown more and more sandbags on the shoulders of an industry that was already struggling as the global price of oil came down."

Evaluating the overall impact of the carbon tax is difficult because of a lack of available data. The policy is two years old, however information gaps still exist. For instance, the most recent data on gasoline sales is two years old, electricity production emissions data is three years old, and natural gas consumption is four years old.

The carbon tax hurt the profitability of the oilpatch, according to Robert Cooper with Acumen Capital Partners.

Oilsands limit

Another key aspect of Alberta’s climate plan is a 100 megatonne per year cap on total oilsands emissions.

The oilsands industry won’t hit the 100-megatonne limit for at least another decade and like many NDP policies, the emissions cap has a mix of supporters and opponents in the oilpatch. Critics wonder why any government would limit the growth of its largest industry.

The emissions cap has been described as a backstop in case the oilsands continue to grow as global oil demand rises. It’s also seen as incentive for the sector to invest in technology to reduce emissions.

Ed Whittingham, the former executive director of the Pembina Institute, a Calgary-based environmental think-tank, was one of the people on stage when the climate leadership plan was announced and he has a framed photo of the event on the wall of his home office. He’s since been appointed to the board of the Alberta Energy Regulator.

The oilsands cap was vital, he said, because people care about total emissions.

"In the climate debate, we really took on the 800-pound gorilla in the corner by putting this emissions limit in place,” said Whittingham in an interview last month.

The cap became law in Alberta in 2016, however the government has yet to determine how to allocate emissions if the oilsands industry approaches the limit, nor has it figured out how to enforce the cap.

An oilsands advisory group recommended the government publish annual data on oilsands emissions and eventually levy fines if the limit is ever breached.

Whittingham said it’s absolutely important to define how the oilsands cap will work "or else it's just an act without teeth,” but said it’s difficult work and the government has to get it right.

He credits the emissions limit, in particular, for putting an end to the frequent oilsands protests by celebrities like Neil Young and Leonardo DiCaprio.

It was vital to put a limit on total oilsands emissions, according to Ed Whittingham.

Phasing out coal

Many large oil and gas companies have a stake in Alberta’s electricity industry, because they either own power plants throughout the province or else produce power at their facilities and sell excess electricity on the grid.

The NDP government has been able to transform the electricity market in the province in a relatively short amount of time.

The carbon tax alone has made burning coal less economical and that’s one reason why natural gas became the largest source of fuel in Alberta for producing electricity in 2018, overtaking coal.

Alberta still uses a lot of coal to produce electricity, however, Notley accelerated the phaseout of those power plants.

Under programs by the provincial and federal government, coal plants must be phased out by 2030. Some of the facilities will close, while others will convert to burn natural gas.

The government announced $40 million to help Alberta coal miners and power plant workers find new jobs or bridge them to retirement. The government also committed to pay $1.36 billion to three companies to shut their coal-fired plants early. Those contracts cannot be broken under a new government.

Meanwhile the government has supported the construction of several utility-scale wind and solar projects, achieving remarkably low prices for the electricity through a bidding process.

“We're paying amongst the lowest prices for new-build electricity, pretty much anywhere,” said Whittingham, the former Pembina Institute executive director. "People may not know, but [the prices are] astoundingly low and puts renewables cost competitive with any form of new-build natural gas facility."

In 2016, the NDP government also set a goal of having wind, hydro and solar provide 30 per cent of Alberta's electricity by 2030.

Suncor's CEO Steve Williams urged the NDP to toughen up Alberta's environmental policies and introduce a carbon tax, while speaking to reporters on May 22, 2015.

Advocacy

No politician in Ottawa or British Columbia has any doubt about where Rachel Notley stands on the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion.

The premier has made the point, again and again, that the project is needed to get more Canadian crude to market to the benefit of not only Alberta, but the country as a whole.

“When Alberta's economy is held hostage, Canada is not working,” Notley said last August after the Federal Court of Appeal stalled plans to proceed with the pipeline project, due in part to the court's concerns about a lack of federal consultation with Indigenous communities.

Echoing the frustration of many Albertans, Notley then announced she was pulling Alberta out of the national climate-change plan to protest the ruling that quashed Trans Mountain.

The premier has criss-crossed the country to argue for the pipeline, extolled the value of the oilpatch and criticized Ottawa’s Bill C-69, an overhaul the approval process for major energy projects.

She also took on a fellow NDP premier, B.C.’s John Horgan, in backing Trans Mountain, and challenged members of the federal NDP in repudiating the Leap Manifesto, which proposed to stop building new pipelines.

"These ideas will never form any part of our policy," Notley said in 2016 following a federal NDP convention in Edmonton. "They are naive, they are ill-informed, and they are tone-deaf.”

But conservative critics question the effectiveness of her efforts, especially the idea of building “social licence” for pipeline development by implementing a carbon tax strategy.

Though Trudeau said in 2016 that Notley’s leadership on climate change was a key reason for why his government approved the Trans Mountain pipeline, her opponents see it as ultimately fruitless.

Nearly three years on, Notley's critics argue, there’s still no pipeline and it hasn’t halted Bill C-48, which would prohibit tankers carrying oil from loading or unloading at ports in northern B.C.

“The NDP's 'social licence' deal with Justin Trudeau has been a miserable failure for Albertans,” UCP Leader Kenney tweeted recently. “Time for a new strategy.”

Yet, an Angus Reid poll released in January found six in 10 Canadians say a lack of new pipeline capacity represents a crisis in the country. Seven in 10 say the country will face considerable impact if no new pipeline capacity is built, according to the poll.

“I would say that she is well known and respected outside of Alberta,” said Lori Williams, a political scientist at Mount Royal University in Calgary.

“She's absolutely clear and unapologetic about being for Albertans, for the Alberta economy and for protecting the environment, striking that balance.”

Not everyone thinks she has struck that balance, though.

“In stark contrast to the reform-minded warrior swept to power three years ago, Notley has morphed into a fossil fuel sycophant, trumpeting the same industry wish list championed by the provincial Conservatives for 47 years,” said an opinion piece in The Tyee, a B.C.-based online magazine with a strong environmental bent.

Four years after the NDP won the election, Tahmazian believes his instincts that Notley would do harm were correct. He gives the Notley government a “failing grade” for its performance.

When the NDP came to power, Alberta was already in an economic downturn and it was a terrible decision to even consider hiking corporate taxes, introducing a carbon tax or reviewing royalties, according to Tahmazian.

"When the industry was down, they layered on. That's what is so shocking,” he said.

In re-shaping the energy sector, Notley has made some big moves in pursuing an ambitious wish list: Acting on climate change, diversifying the energy sector, and creating more jobs in the industry, among others.

Individually, the policies each represent significant change for an industry, such as the limit on total oilsands emissions and raising taxes.

Collectively, they represent an overhaul of the sector with some specific actions that would be difficult, or expensive, for a new government to stop, such as the subsidies for new petrochemical facilities, long-term contracts for renewable energy projects and leasing thousands of rail tankers.

The Flames appear to be heading back to the playoffs this year. Depending when the spring election is called, thousands of people may be sitting in Saddledome seats again when they find out what’s in store for the oilpatch for the next four years.