June 4, 2018

On Nov. 10, 2016, a group of masked men stormed a bank in Otun Ekiti, a small, dusty town in southwestern Nigeria.

In a hail of bullets, they killed a bank teller, two security guards and the manager, Modupe Segun-George.

Although Segun-George wasn’t the only one who died, his wife, Modupe Idowu Agnes, says he was the ultimate target of the attack.

According to her official statement provided to Canadian authorities, at the time of his death, Segun-George was looking into fraudulent loans approved by his superiors at the bank. Even before the attack, he had been the target of threats that made him fear for his family’s safety. But Agnes says police did “little or nothing to investigate” those threats.

Segun-George’s autopsy report said he died of “traumatic brain injury” after being shot in the head.

After her husband was killed, Agnes worried she and their three children could be next, but she couldn’t stay quiet. She pressed police to find the killers. Instead, Agnes began to receive threats of her own, including text messages like this one: “The police is in our pocket, don’t think you are protected, your husband was not.”

One day, while driving her children home from school, she was forced to stop the car. Someone had placed a giant log across the road, blocking her way. Agnes feared it was the same people who killed her husband. She made a quick detour, packed the family’s bags that night and never returned home.

Agnes came to Canada seeking asylum for herself and her children, taking a now-familiar route from the U.S. through an unofficial border crossing in Quebec. More than 7,600 people have entered Canada outside official border crossings so far this year, and over half of the new arrivals are from Nigeria.

Yet it’s one of the realities of the immigration system that despite such a brutal experience, there’s no guarantee Agnes’s family will be able to stay.

II.

Last month, Agnes turned up at Mariama Diallo’s Montreal office with a folder full of documents, including autopsy results, a death certificate and newspaper stories about the killing.

“These are not the claims I usually get: photos, police reports,” Diallo says. “It’s a strong case, in my opinion.”

She acknowledged, though, that the danger Agnes claims to face in Nigeria will be difficult to prove. If her refugee claim is rejected, she plans to make a case on humanitarian and compassionate grounds.

Until recently, Diallo practised a mix of family, criminal and immigration law, but increasingly, her clients are refugees. She now represents more than 200 refugee claimants and almost all of them — “99 per cent,” she says — are from Nigeria. It started with a single client last November, and word spread.

Many of them are well-educated, she says, and had good jobs in Nigeria. Their reason for fleeing may be more economic than safety-related, but it’s not without risk.

“Mostly, they are selling their cars, their houses, everything, because for them it’s the last resort,” Diallo says. “You sell everything and you try to find a better life for your family, yourself and your kids.

Nigeria, which competes with South Africa for the title of the continent’s largest economy, was driven into recession in 2016. The slumping price of oil and inflation have made life more difficult for the middle class in Nigeria. The uncertainty has driven many to leave.

An increasing number of Nigerians have been immigrating to Canada through official channels, using Canada’s “express entry” program that fast-tracks skilled workers. More than 1,000 arrived in 2016, the most recent year available for the program, compared with 98 a year earlier.

There are, however, very real threats in Nigeria. The most recent country report from Human Rights Watch details a long list of concerns, including the continued presence of the Islamist group Boko Haram in the northern part of the country, violent disputes over pastoral land and “corruption and mismanagement of public resources” under President Muhammadu Buhari, who took office in 2015.

Agnes says the breakdown of trust in the government is driving people to leave.

“You can see my own situation now — different cases like that happen to many people in Nigeria, and nobody is ready to help.”

Agnes claims she and her family could be killed if they are forced to return to Nigeria.

III.

Agnes and her family didn’t intend to come to Canada. They arrived in the U.S. last August on a tourist visa, but Agnes was unable to secure a work permit, and with her savings, she struggled to provide for her children, Timmy, seven; Folarin, 11; and Richard, 13.

Agnes initially planned to claim asylum, but U.S. President Donald Trump’s tough talk about illegal immigrants had her worried.

Agnes and the kids were sitting in their apartment in Midland, Tex., last year when they saw a story about asylum seekers in Canada on the TV news.

“We saw how [authorities] are attending to them, how they are giving them food,” she says.

To find out more about how to make a claim, Agnes didn’t turn to a fixer or a secret network on social media. Her daughter, Folarin, Googled it.

Stories popped up about Roxham Road, Canada’s busiest illegal crossing, between New York and Quebec, where thousands have walked into Canada to claim asylum.

A few months later, they made the journey themselves. They packed everything they could into a few suitcases and made their way to the border. The well-trodden route includes a flight to New York City, a bus ride to Plattsburgh, N.Y. and a taxi to Roxham Road, where they cross into Canada.

It was middle of the night on March 29 when Agnes and her children arrived at the Canadian border. At the end of the long journey, her children began to cry.

“I was scared, because they say if you cross the border, you get arrested,” Folarin recalled.

But she collected herself, she says, and they walked into Canada. “I knew I had to put my mind together and be calm.”

They handed over their passports and belongings and were taken into custody. They were questioned, fingerprinted and, eventually, taken into the care of the Red Cross. They spent the month of April in a Montreal shelter set aside for asylum seekers.

The city has struggled to accommodate the influx of arrivals. Last summer, when there was a spike in arrivals from Haiti, authorities had to open up the cavernous Olympic Stadium.

The Quebec government has maintained that won’t be necessary this summer, but it has appealed to the federal government for more money and resources. It also wants Ottawa to help asylum seekers quickly relocate to Toronto or elsewhere in Canada if they don’t plan to stay in Quebec.

More than 75 per cent of the Nigerians who have crossed illegally this year did so with a valid travel visa to the U.S. Late last week, Ottawa announced an additional $50 million to help house asylum seekers.

Agnes has no plans to leave Quebec. She moved into an apartment block at the end of a quiet residential street in Pierrefonds, a suburb in Montreal’s West Island, at the beginning of May. The rent is $750, and she has to share a bedroom with her three children. Nearly everything in the apartment — the couch, chair and television — was donated. A hutch she found in an alley is among her prized possessions.

Agnes has a work permit, but for now, she relies on a monthly social assistance cheque of just over $1,000. To feed her family, she takes the bus with her kids to a nearby food bank and, sometimes, an African store she discovered — the spices remind her of home.

Agnes arrived too late in the school year to register her children in school. In the fall, when they are enrolled, she hopes to get a job or take French lessons.

“Just to survive, I can do any work,” Agnes says. She lists off a few options: cashier, cleaner, caretaker for the elderly.

Agnes bought an old French-English dictionary that stays on the coffee table. The children, who, like Agnes, speak Yoruba as well as English, use it to quiz one another.

The kids were given some schooling during the month in the shelter, and were able to pick up a few words of French.

“I know how to say greetings and the parts of the body,” Folarin says proudly.

Agnes dreams of being able to start a new life in Montreal, “because I know I will be protected here, so my life is safe and the life of my children is safe.”

IV.

Diallo always cautions her clients at the outset that they may not be allowed to stay in Canada.

“I tell them, based on their story, you know, these are the grounds they are looking for. To have a refugee claim, you must be at risk,” she says. “It’s not because you came in and made a refugee claim that you will be accepted. For sure, most of my clients will probably not get it based on the results we’ve been having lately.”

In the first three months of 2018, only 178 cases presented by Nigerians were accepted. Another 359 were rejected, 48 were abandoned and 16 were withdrawn. The bulk of the claims are still being processed.

Less than 15 per cent of the claims made by Nigerians the year before have been approved. The majority of those are also still pending.

The slow process and low odds of having their claim accepted can come as a surprise to asylum seekers, despite recent efforts by the government to stress those realities.

“That’s not what they hear from the shelters, from the news, or whatever,” Diallo says. “What they hear is that you’re going to have a letter from immigration or just a group decision saying they will all be accepted, so we have to go forward and explain that’s not the case.”

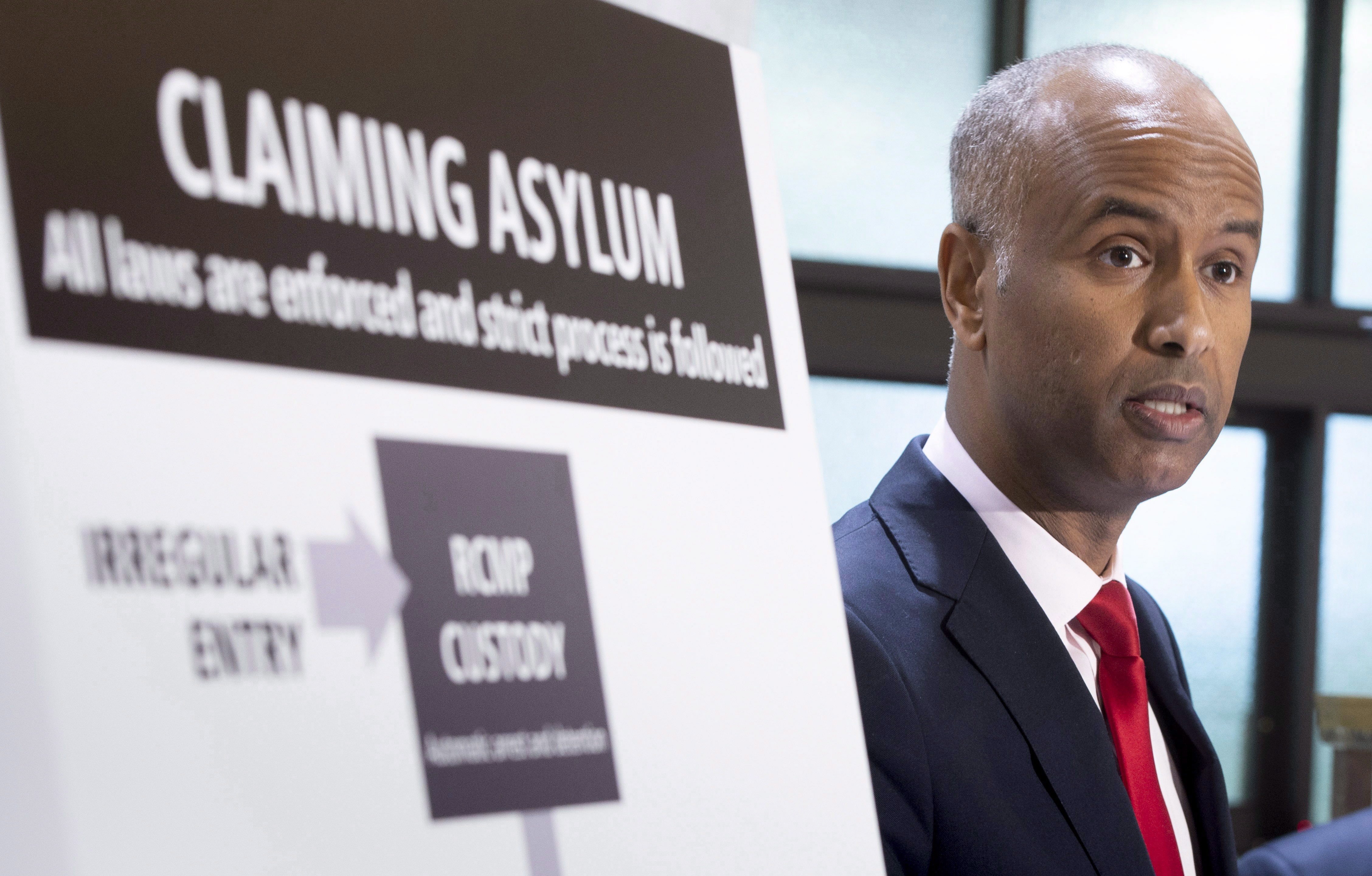

Canadian Immigration Minister Ahmed Hussen visited Nigeria last month to meet with senior officials in attempt to put an end to the rise in the number of Nigerians using U.S. travel visas to enter Canada illegally. Those officials, including Nigeria's foreign affairs minister, promised to help tackle the problem by spreading a "deterrence" message.

V.

Agnes has been following these developments, but is hopeful her own case is strong enough to allow her to stay.

One morning last week, Agnes took her children to the park near their apartment — a playground and swing set surrounded by old maples and dark green grass. Richard and Timmy, his younger brother, tossed a plastic, deflated football back and forth.

Folarin laments not having been able to celebrate her birthday last month with friends — and her father. She is also anxious to start school. Folarin was one of the top students at her school in Midland, Agnes says.

But the transition — and this period of extended limbo — hasn’t been easy.

The days are long. The children can spend hours playing board games (their favourites are Snakes and Ladders and Perfection). They play video games on Agnes’s phone. They watch TV.

Agnes was originally given March 1, 2019, as her hearing date for refugee claim. Last month, she received a letter saying it would be postponed indefinitely. The current wait for a hearing is 18 or 19 months.

By then, refugee claimants are often well-established in Canada, with a job and children enrolled in school.

At this point, Agnes is still learning the basics of survival in suburban Montreal.

She knows almost no one, except a neighbour who lent her a blender — another Nigerian woman whom she met in the shelter, and who informed her of the vacancy in the apartment building.

Agnes’s chances of staying aren’t good. Yet she isn’t prepared to face that possibility. When asked if she’s fearful her claim will be rejected, Agnes appears at first not to understand the question.

Then she responds, “I know they won’t.”

Her confidence that the government will let her stay seems to stem from her conviction that Canada is where her family is meant to be.

“We want to stay here,” she says. “We want security, we want to live as citizens here.”