November 11, 2018

The pillars on the Kelly House apartment block stand as a reminder of one of the biggest political scandals to rock this province.

More than a century ago, a conspiracy to use the construction of the Manitoba Legislative Building to funnel money into a secret election fund brought down the provincial government and sent one of Winnipeg's wealthiest developers to prison.

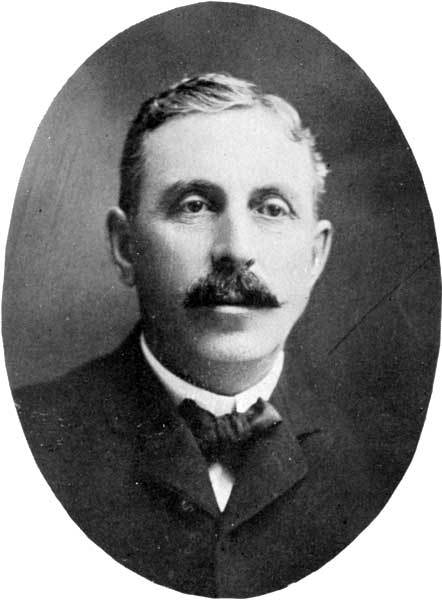

Hundreds of thousands of dollars were fraudulently paid to contractor Thomas Kelly, who kicked the money back to the Conservative Party of Premier Rodmond Roblin. In their efforts to cover it up, government officials destroyed documents and bribed a witness into exile, a commission of enquiry later found.

After Kelly was sentenced to 2 ½ years in prison for his role in the scandal, the province seized his grand mansion at the corner of Carlton Street and Assiniboine Avenue.

Today, seven limestone columns are all that remain of Kelly's mansion, incorporated into the apartment tower that stands in its place.

Bob Kelly, great-great-nephew of Thomas Kelly, lived in the building with his wife in the mid-1970s.

The scandal caused a rift in his family, he said.

In 1954, Bob's grandfather made his mother burn many documents related to the investigation, he said. His grandfather watched from a window as his mother dropped one sheet of paper after another into a metal bin outside.

"They were pretty devastated by the whole accusations and their name being involved and dragged through it," he said. "They were trying to protect us."

Among the crimes his great-great-uncle committed, there is one he is almost certainly innocent of despite a stubborn urban legend.

"There was always the accusation that these pillars came from the leg., and in my family, as far as I know, that was always denied," Bob said.

Anyone who has taken a tour of the neighbourhood around the legislative building has likely heard the legend of the Kelly House pillars. Construction workers repairing the exterior told CBC News they have heard the story, and a property manager said the same thing — that they were taken from the materials meant for the legislative building.

That story begins to fall apart, however, when you look at the construction dates for the house and the legislative building. The house was built in 1909, while the contract to build the legislative building wasn't awarded until 1913.

Local history blogger Christian Cassidy points to an early colourized photograph of the house used in an advertisement, circa 1916, which shows the pillars on the house. The original photo is likely from 1912 or 1913, before construction on the leg. began, he said.

The earliest mention in print of the rumour about the pillars appeared in an October 1965 Winnipeg Tribune article. Writer Lillian Gibbons attempts to debunk the rumour, but by the 1970s, articles about the house reported the rumour about the pillars as fact, Cassidy said.

"Nobody ever questioned it, so it just kind of became urban legend after that," he said.

The origin of the rumour about the pillars is unclear, but Bob Kelly suspects it was used to distract people from the real scandal — that the wrongdoing reached all the way up to the premier.

"There was so much corruption on the building of that building that they needed something to charge somebody with," he said. "I'm not trying to say that he was innocent. He wasn't the main character."

Thomas Kelly's family emigrated from Ireland in the mid-1860s, settling in New York before moving to Winnipeg in 1874, one year after the city was founded.

Winnipeg was booming and the Kelly brothers quickly found success as contractors on public construction projects.

"We forget that it was rough and wild here in Winnipeg," said Winnipeg historian Ron Robinson. Around 1900, Winnipeg had a saloon for about every 200 residents, according to a biography of former Manitoba premier Hugh John Macdonald written by Keith Wilson. In 1905, Winnipeg had the highest rate of typhoid deaths of any city in North America.

Through their various companies, they built some of the city's first concrete sidewalks, roads and bridges. Later, they built a portion of the Shoal Lake aqueduct, the Grain Exchange Building, the Agricultural College at the University of Manitoba and the Law Courts Building.

Through these building contracts, Kelly made connections with Rodmond Roblin's Conservative Party.

When bidding opened on the contract for the legislative building — at the time called the New Parliament Building — Roblin let Kelly look at the winning bid and then extended the deadline, allowing Kelly to submit a new bid at a lower price and win the contract.

Once construction began in 1913, Kelly started inflating invoices in conjunction with members of the Roblin administration. He substituted cheaper materials for the ones listed on on the contract and lied about the amount of steel, concrete and other material used.

The royal commission that investigated the construction scandal found the province overpaid Thomas Kelly and Sons $892,098.10. In today’s dollars, that would be worth more than $19.5 million. Much of this money was then funnelled into an election fund for the Conservative Party.

When the Opposition Liberal Party started cry foul over the rising cost of the project, the government began trying to cover up the operation.

Provincial architect Victor Horwood, in consultation with acting public works minister George Coldwell, paid a provincial inspector, William Salt, $10,000 to go into hiding in the United States. Salt had doctored his books to make it look as if the amount of materials used matched what the province had paid for, but government officials worried he wouldn't stick to the story under questioning.

Salt was sent to Denver, Colo., and a man was sent from Winnipeg with an envelope containing the money. When the man reached Omaha, Neb., however, he was either robbed or stole the money for himself. Either way, he returned to Winnipeg and received another $10,000 for Salt.

By this time, Salt was growing impatient and he set out to return to Winnipeg.

A lawyer acting for the province then hired a private investigation firm to convince him not to return.

"By dint of much negotiation and some threats, as to what the government would do to him if he returned to Winnipeg," Salt was convinced to accept the $10,000 in exchange for silence, the commission wrote in its report.

Horwood went to Minnesota, ostensibly for an operation, and Thomas Kelly fled to Chicago but was extradited back to Manitoba to face trial.

Growing public outrage forced Roblin to resign on May 12, 1915, and the Liberals, under Tobias Norris, came to power and called the royal commission that eventually unearthed the story.

Charges were brought against several government officials, including Roblin, but Thomas Kelly was the only one sent to prison.

He was sentenced to 2 ½ years in prison, but only served nine months in Stony Mountain Institution. Reports at the time said he never spent time behind the prison bars, instead living in a room in the warden's house or in an open cell on a floor of the penitentiary with no other prisoners.

When he was released, Kelly went to Kansas City, where he set up another construction company. After running into legal troubles there, he went to California, where he found wealth in the oil business.

He died in Beverly Hills in 1939.

In Manitoba, the Norris government overhauled the civil service, which up to that point had been appointed on a system of patronage.

"Finally, the stench was so strong, we now had a great demand to have a civil service that was just that, that was hired and promoted on merit, instead of you are a member of the party in power," said Robinson.

Kelly's mansion became a barracks for the RCMP and a boarding house in the 1930s, before becoming a series of hotels and restaurants until it was demolished in 1965.

While the story of the stolen pillars might not hold up, they stand as a reminder of a different era of politics in Manitoba.

"That's a physical emblem to represent it — the truth is, yes, it was as bad as you think it was," said Robinson.