In the days after a massive earthquake led to the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster, Meng Wanzhou flew into Japan as most people were leaving.

“There were only two people including myself on the flight,” she told students at Beijing’s Tsinghua University in 2016.

The Huawei chief financial officer has told the story a few times.

Huawei engineers clad in protective suits risked radiation poisoning to repair communications equipment near the damaged reactor.

“Aftershocks drained the blood from our faces in the beginning,” Meng told her audience.

“But we gradually got used to them.”

Although she has claimed she is reluctant to seem like she’s bragging, Meng recalled those days recently in the wake of a new, more personal disaster: her arrest in Vancouver on a warrant seeking her extradition to the United States for allegedly helping Huawei violate sanctions in Iran.

In a diary excerpt posted to the company’s website within days of her release on $10 million bail, Meng claimed to have received a letter from a Japanese fan who remembered her bravery during the Fukushima crisis — and who wanted to wish her well.

Meng said her lawyer told her his office had been inundated with similar sentiments.

“I couldn’t help but burst into tears,” Meng wrote.

“I wasn’t crying for myself; I was moved by the thought that so many people had trust in me.”

It’s a rare glimpse into the psyche of a woman who will once again hold the world’s attention when she makes her next appearance in B.C. Supreme Court in May.

Meng’s fate has had repercussions well beyond the courtroom: Canadian canola farmers face the prospect of economic ruin as China blocks imports; two Canadians are in jail in Beijing, accused of spying and a third accused drug trafficker is on death row.

Canadian politicians claim it’s all retaliation, a charge the Chinese deny. Regardless, the situation has put a focus on Huawei’s hopes to dominate the 5G technology markets of the future and the security implications for countries like Canada.

No matter how her extradition battle resolves itself, it’s worthwhile considering the speeches and court affidavits that provide the only insight available into the person behind the headlines.

Meng comes off as — by turns — both modest and boastful. She is the daughter of one of China’s most powerful men, a billionaire who rose from humble beginnings to build the world’s largest telecommunications company, yet she has strived to make her own mark in the business.

And perhaps most surprising, given that she finds herself at the dead centre of a trade war between the United States and China, she represents a generation of Chinese who appear to have modelled their futures on a very American idea of success.

For now, though, Meng’s world is very much confined to a virtual jail that sees her living under house arrest, forced into her westside home between the hours of 11 p.m. and 6 a.m. and restricted the rest of the time to areas of Richmond, Vancouver and North Vancouver delineated by yellow highlighter on a court-approved map.

The ferry terminal and airport are both out of bounds.

Meng wears a GPS ankle bracelet and is escorted everywhere by security guards she pays to ensure she doesn’t flee.

On a recent Monday morning, the blinds behind the windows of Meng’s grey, multi-million dollar corner lot house remained closed as a black Cadillac Escalade patrolled the block.

A tall, older man holding a clipboard unfolded himself out of an ever-present grey BMW sports coupe as a pair of Chinese men neared the home. The visitors paused at a knee-high stone wall to sign in. The watcher returned to his car as the two men proceeded to the entrance and inside the house. A tiny white rocking horse sat beside the door.

The $5.6 million two-storey home is Meng’s new headquarters — the place where strategies for both Huawei’s global 5G plans and Meng’s personal liberty will presumably be hatched.

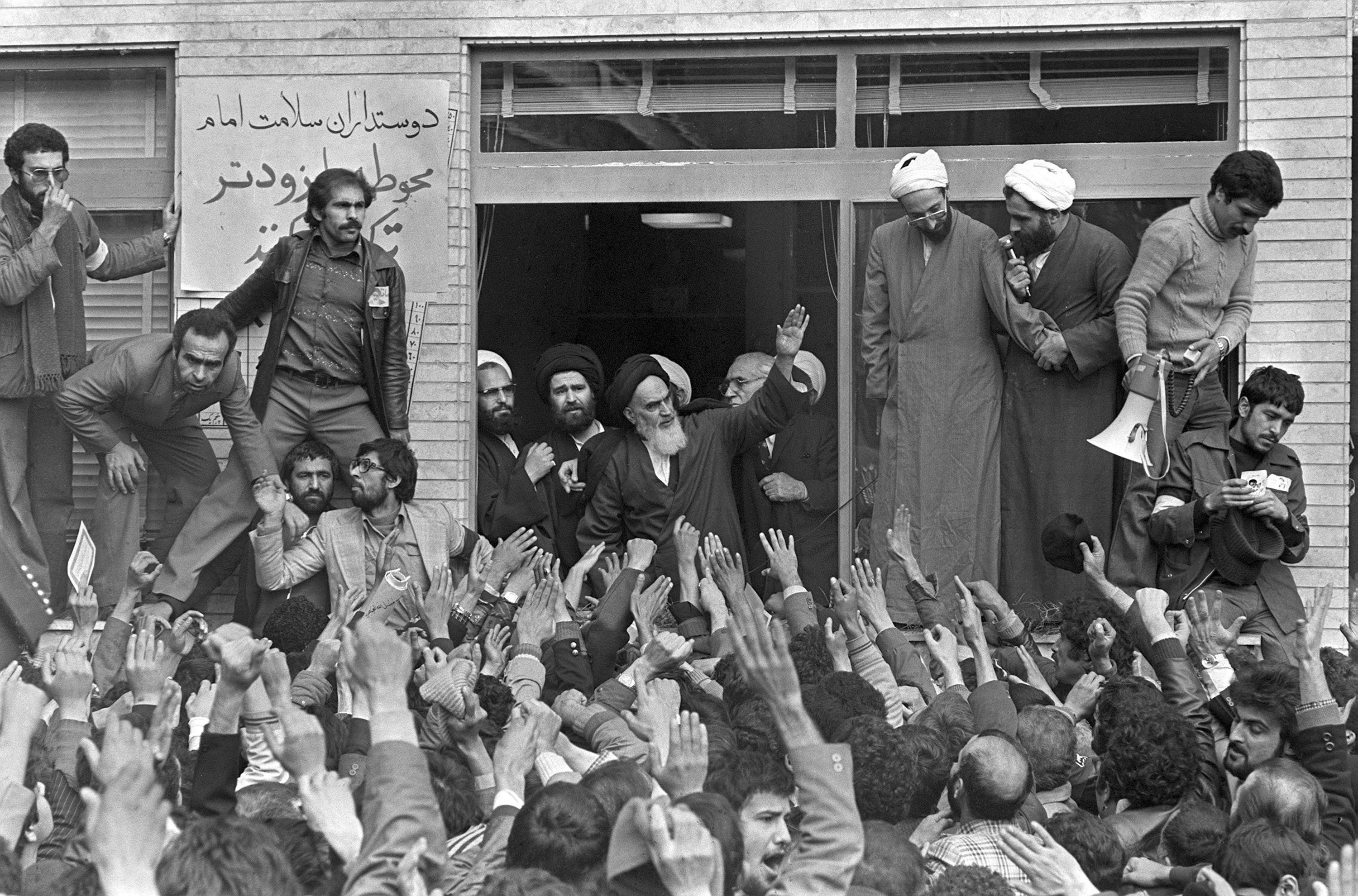

Meng was still a child when radical students in Iran seized the U.S. embassy in Tehran in 1979, bringing the brutal regime of the Shah to an end. The revolution heralded the return of the Shia cleric Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini and the establishment of an Islamic republic.

The radicals also held 52 American embassy staff hostage for more than a year, humiliating a superpower and sparking the bitter animosity between Iran and the U.S. which continues to this day.

The conflict also drew the international sanctions that would allegedly lead Meng Wanzhou into legal peril nearly four decades later.

The case illustrates the challenges facing multinational companies intent on reaping profits in a world riven by conflict and competition. Companies like Huawei operate in every corner of the globe and inevitably politics and commerce collide.

Decades of sanctions have seen Russia and China emerge as Iran’s biggest trading partners. Iranian oil is crucial to the Chinese economy. And the demographics of Iran — a youthful, urban population of more than 80 million — make it an attractive market for many companies.

Americans are forbidden from doing business with Iran. Period. But the sanctions also prevent the sale of certain U.S. goods into the country by others, particularly technology that could be used by the military or the state to monitor citizens or intercept communications.

It’s not unusual for Chinese companies to do business in Iran.

But there is a huge risk of doing the wrong kind of business — and of using the U.S. banking system to convert money made from those deals into dollars.

And that’s exactly what prosecutors claim Meng and Huawei were doing through their association with a company called SkyCom, which is accused of violating sanctions by offering to sell Hewlett-Packard computer equipment to Iran’s largest mobile phone operator in 2010.

Meng served on the board of directors for SkyCom.

The U.S. claims that while Huawei said SkyCom was simply a local partner ‒ the firm was in fact a front for Huawei.

And that Meng lied to banks about the relationship when they questioned her in 2013.

It’s not like Meng didn’t know these allegations were out there. A U.S. congressional report accused Huawei of flouting international laws in 2012.

And in a speech in New York in 2014, Meng made a deliberate point of assuring the world that Huawei felt a moral duty to respect international norms.

“We must comply with laws and regulations of the countries in which we operate, maintain order in the marketplace, strive to provide our customers with superior services and ensure Huawei’s healthy and stable growth,” Meng said to an audience that included former U.S. Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan.

The words were part of a keynote address for a Huawei financial forum, spoken in front of an audience of 500. Given the later turn of events, the speech is remarkable for what it reveals about Meng’s views of the country which would later seek her detention.

“In the future, we will continue to learn from the U.S.; in fact it will be our teacher for a long time,” she said.

“The U.S. is a country that has given birth to the most advanced society and countless individuals.”

She name-checked Apple’s Steve Jobs — “a hero in the digital age” — just as she would later praise Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg and Tesla’s Elon Musk for “changing the world” in the same presentation where she described her experience at Fukushima.

Meng’s father, Ren Zhengfei, could also be considered part of that club. The former military engineer started Huawei in 1987, bringing cable to China’s rural population before building a global brand by penetrating markets overlooked by western companies like Africa, Russia and India.

Judging by their public statements, Meng and her father have — at best — a distant relationship. She was born in 1972, two years before he joined the army.

“The reason we are not close is that when she was little, I joined the military,” Ren told the Financial Times earlier this year.

“For 11 months out of a year, I couldn’t be with my kids. For one month I was back home, they had to go to school and do their homework after dinner.”

Questions about Ren’s connections to the Chinese state and the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) have dogged Huawei for years, leading to American legislation introduced the summer before Meng’s arrest banning U.S. government agencies from purchasing specified Huawei equipment or dealing with third parties who use it.

But at the same time U.S. congressmen have been accusing her father of being a secret commander in the PLA and even calling for “the death penalty” for Huawei as part of an effort to keep the company out of the U.S. market, Meng has risen to prominence at Huawei by championing partnerships with American corporations like IBM.

Her fondness for all things American appears to stretch well beyond the theoretical.

According to court documents, Meng had an iPad Pro, a Macbook Air and an iPhone 7 Plus on her when she was arrested. She was only carrying one Huawei product.

She paid nearly $60,000 a year for her son to attend an elite Massachusetts boarding school; the principal would later provide a character reference for her bail proceedings.

“Let me know if there is anything I can do as I think the world of her and her family,” wrote Andrew Chase, headmaster of Eaglebrook School.

“I do not believe she would violate any court order.”

Meng’s husband Liu Xiaozong also has deep connections to the U.S. Like Meng, who is also known as Cathy or Sabrina, Liu has his own anglicized business name: Carlos.

He earned his Master of Business Administration from Chicago’s Kellogg Management School in 2009. A former Huawei executive, Liu started his own management company in 2012 and later founded an education investment firm which reportedly runs a high-end foreign language school.

According to the website of the Council for Advancement and Support of Education (CASE), which held a conference in Shenzhen in October 2018, Liu spoke as a panelist about efforts to cultivate “an American-styled philanthropic practice among Chinese parents.”

He also told attendees about the ways international schools might learn to tap into the deep pockets of the Chinese elite who send their children overseas to study.

But the conference records themselves illustrate the sensitivities around the Meng case and the way in which the extradition proceedings appear to be influencing the future while altering perspectives of the past.

After the CBC contacted Washington-based CASE to ask for a transcript of the proceedings, both Meng and Liu were removed from the page listing co-chairs and speakers.

The couple face the prospect of a long stay in Vancouver; extradition cases can take years to resolve and the issues at play in Meng’s case mean that it’s almost certain any decision in the case will ultimately land with the Supreme Court of Canada, the federal justice minister — or both.

In the meantime, Meng keeps herself to herself.

At her bail hearing, her lawyer spoke about her desire to use her time under house arrest to her advantage. If anything, he suggested, a little downtime might come as a relief.

Meng has battled thyroid cancer and hypertension on a schedule that she claims has made it impossible for her to finish a novel in decades. If granted the time, she said she wanted to read, concentrate on family and perhaps even consider pursuing a master’s degree.

She has maintained her innocence from the outset.

Her reminder about the Fukushima incident ended with the suggestion that no matter how long the battle, no one should underestimate Meng’s willingness to fight.

“I was so proud of myself for mustering the courage to board that plane to Japan in spite of the risks,” she wrote.

“I was brave not because I was not scared, but because I had faith.”