March 6, 2018

Tesfamichael Abraha’s home is a little Eritrean haven in the middle of Yellowknife’s frozen sub-Arctic landscape.

His son Zechariah, 22 months, dances to Eritrean music in front of a flat-screen television while Tesfamichael’s wife, Abbeba, makes injera and various curry dishes in the kitchen. After dinner, she pulls a portable stovetop into the living room and heats a pan. Soon the room fills with the scent of roasting coffee beans. She’s making traditional Eritrean coffee, spiced with ginger. The sound of Tiringya, the family’s mother tongue, fills the house.

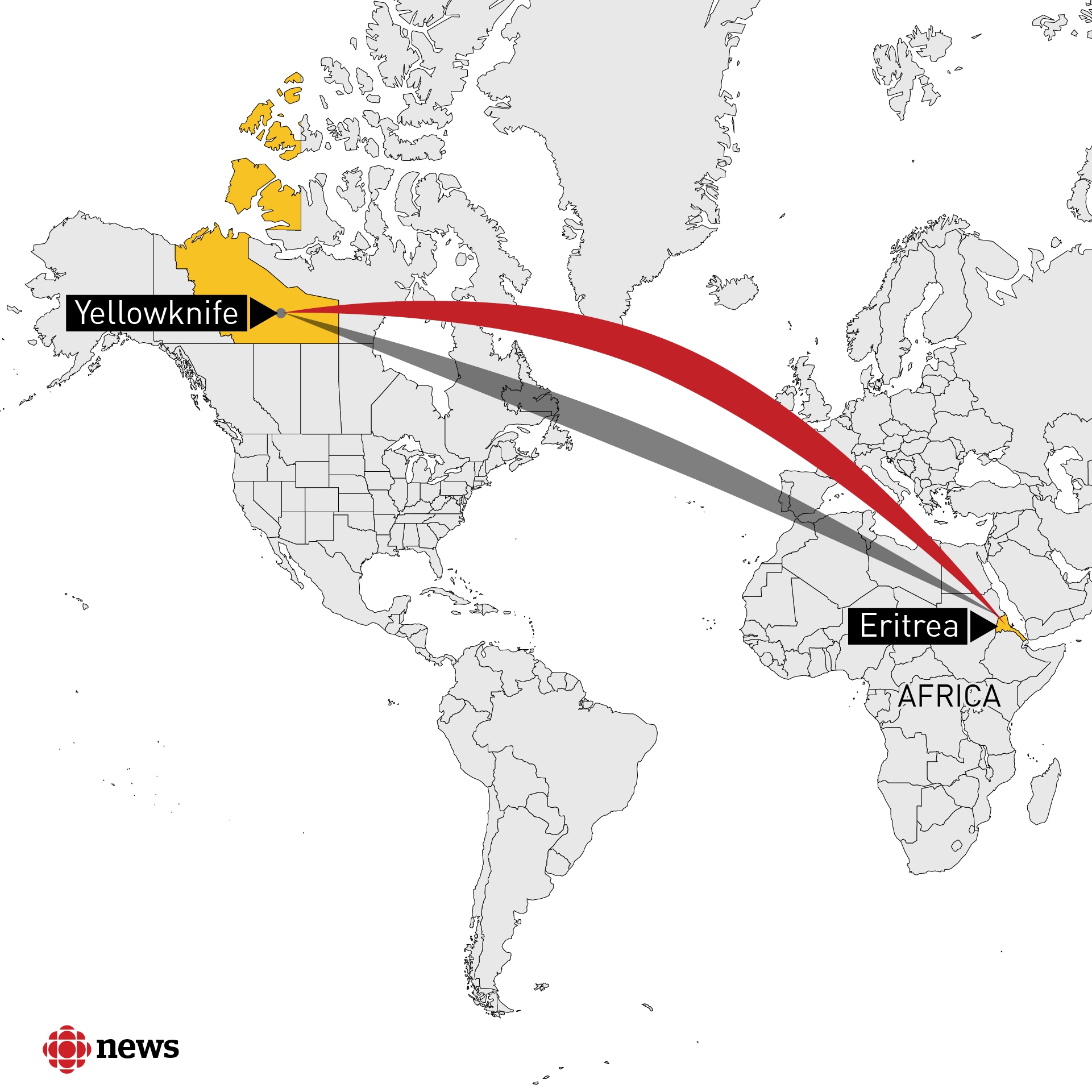

Ten years ago, Tesfamichael took a big risk: he left his wife and two daughters in the village of Aregen, Eritrea — a tiny country that borders Ethiopia in East Africa — in search of a better life for himself and his family.

Today, he’s helping more family members escape a despotic government widely known to perpetrate crimes against its own citizens.

He says he wouldn’t be able to do it if it weren’t for a friendship his family struck with Mona Durkee — a Yellowknife woman the family has grown to call their “Canadian mom."

A fateful visit

Tesfamichael credits his arrival in Canada to a stroke of luck.

He escaped Eritrea in February 2008 at the Ethiopian border. He walked for a week, avoiding settlements during the day to deter detection. For food, he picked gaba, a prickly fruit that grows in Eastern Africa. He carried jerry cans for water — sometimes he could fill them, sometimes not, depending on the area.

“I was very tired and sick,” he said.

When he made it to Sudan, he was able to catch rides, but the travel wasn't any easier. As many as 15 people would pile into the back of a small truck under the hot desert sun. People in his group died along the way from thirst, heat and hunger. Some were reduced to drinking their own urine to stay alive, said Tesfamichael.

“It’s desert ... it’s very, very bad,” he said.

“It’s dry. You start crying actually, the women start crying, ‘We gonna die, we gonna die.’ And we had to pray, pray, pray.”

When Tesfamichael reached Egypt, he was imprisoned in the southern city of Aswan, for crossing the border illegally.

“It was 10 to 12 people in [a] small container,” he said.

“It was hard. It was like, one time per day they give you food.”

Abraha described his one daily meal as a “salted yogurt.”

Then one day, after about 16 months, officials from the United Nations High Commissioner of Refugees (UNHCR) showed up to inspect the prison.

This would be a rare occasion, according to a UNHCR document accounting for the agency’s activities during this time period.

"We had to pray, pray, pray."

“Hundreds of Eritreans were detained and deported from Egypt, despite UNHCR’s appeals to the authorities of both countries to refrain from forcible return and grant the office access to detention centres,” states the document.

“With the exception of a group detained in the Aswan prison in Egypt, UNHCR was not permitted access to detained Eritrean asylum-seekers, nor did it receive any verifiable information about them.”

After discovering him in prison, UNHCR found asylum for Tesfamichael. Within weeks of his rescue, he arrived in Canada.

In August 2009, his wife Abbeba Kesete, who had been waiting in Eritrea with their two children Mizer and Rufta, received a phone call from Canada. For the first time in 18 months, she heard Abraha’s voice.

“After one year, six months ... he comes to Canada, calls me, says, ‘I’m happy,’” she said.

‘A campaign to instill fear’

Eritrea is an authoritarian state with no independent judiciary or democratic institutions.

A 2016 United Nations inquiry found widespread and systematic crimes against humanity in the country, which was founded in 1991 after a brutal 30-year war with Ethiopia.

The UN Commission of Inquiry on Human Rights in Eritrea found Eritrean citizens are regularly enslaved, imprisoned, disappeared, tortured, persecuted, raped and murdered “as part of a campaign to instil fear, deter opposition from and ultimately to control the Eritrean civilian population.”

According to international non-governmental organization Human Rights Watch, thousands of Eritreans flee the country on a monthly basis to avoid government mandated indefinite conscription to the military.

As for Abraha, he left to give his family a chance for a better life.

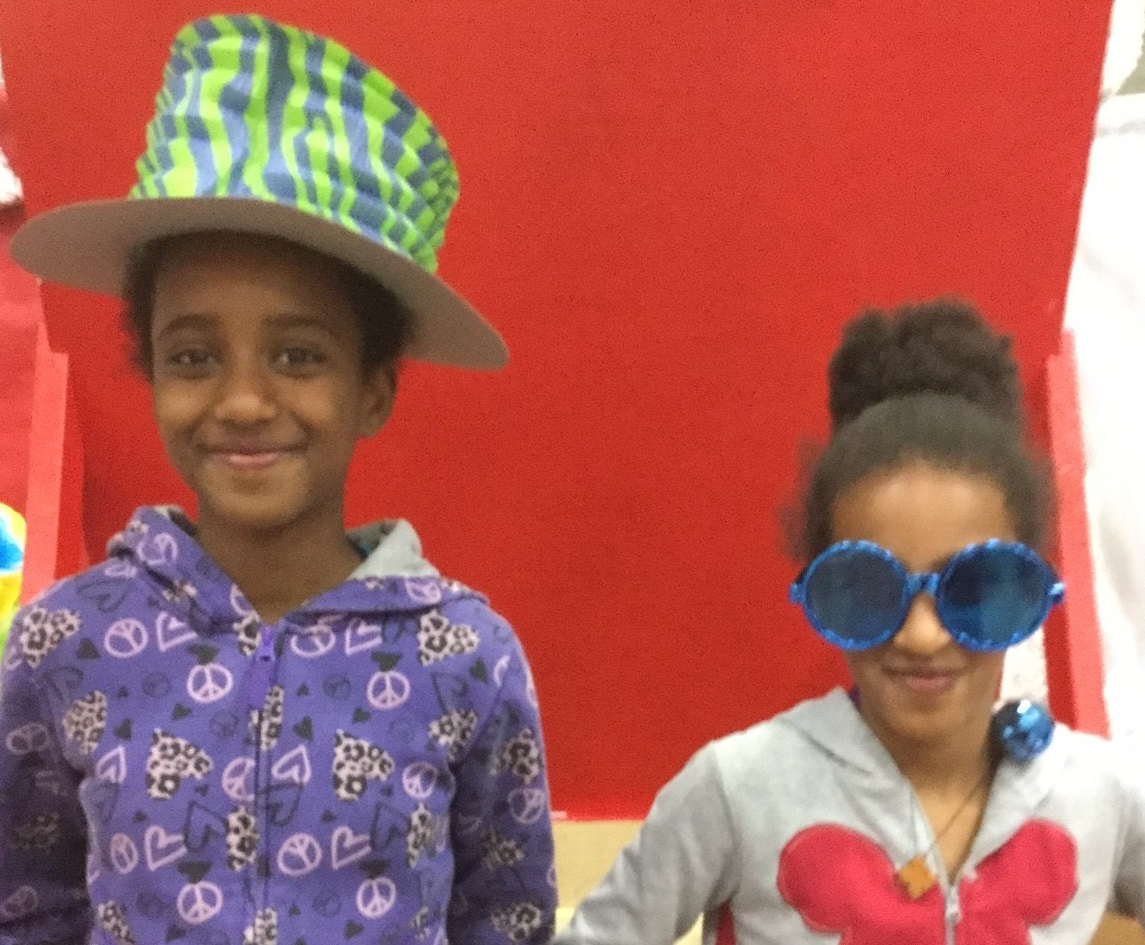

Mizer, 12, and Rufta, 10, study at Yellowknife's St. Joseph School, where they take part in archery and basketball.

“They need to have [a] future,” said Abraha, describing the nicknames he and Abbeba give their children that reflect their hopes for them.

“For Mizer it’s like, 'Dr. Mizer.' For Rufta it’s like, 'Engineer Rufta.'”

Yellowknife via Newfoundland and Winnipeg

When Tesfamichael first reached Canada, he tried to settle in Newfoundland, but he couldn’t find work that would support his family. He moved to Winnipeg soon after, where he started taking English classes, but found the same problems there.

“I couldn’t afford rent, house, clothing,” he said.

“I had ... full-time and part-time work and go to school and … I couldn’t afford [to support] myself and my family.”

Through the grapevine, Tesfamichael heard about Yellowknife. A friend told him about a man there who might be able to help.

So he called a man named Abraham, and came away from that conversation with an offer of housing until he was settled.

Tesfamichael made the jump in 2011.

“They take me, drove my resumé anyplace to get a job and after a couple days I got a job,” he said.

A year later, Abbeba, Mizer and Rufta were cleared to join him in Canada.

According to the 2016 census, 30 Eritreans call Yellowknife home. Tesfamichael and his family have struck friendships with many of them.

“I know so many,” said Tesfamichael, listing off their names.

His family regularly feasts with the other Eritreans in town during Eritrean Orthodox Christian holidays, such as Christmas and Easter.

‘My Canadian mom and dad’

The first hurdle for Abbeba was learning English, something she started right away through Aurora College’s Language Instruction for Newcomers to Canada program.

It was there she met Mona Durkee, a woman the family now refers to as their “Canadian mom.”

Durkee first bonded with Abbeba over spices. Durkee cleaned out her spice drawer and made a poster with the name of each spice. They made their way through the collection, tasting and sharing their words for each flavour.

“After that we got together weekly to play games, learn a little bit about language and turn-taking and just to enjoy each other,” said Durkee.

She helped the family paint their home, took Abbeba grocery shopping for the first time, provided child care, helped Abbeba through her pregnancy with Zechariah, her third child, and over the course of time developed a tight bond with the family.

“Oh, Mona’s ... family. Like mom. And Art [Mona’s husband] like dad,” said Tesfamichael.

“They come to us, they see what we need. It’s like what your family do … That’s my Canadian mom and dad.”

Durkee is a member of Yellowknife’s Christian and Missionary Alliance Church. Through the church’s head office, she’s learned how to navigate the maze of paperwork needed to file applications for refugee sponsorship.

She’s currently helping Tesfamichael and his family through their own application process. They are working to sponsor a niece and three nephews — one with a wife and daughter — to join them in Yellowknife.

Tesfamichael’s niece, Freweyni, could be arriving imminently. In February, the family was notified she had passed her interview and medical exam and was waiting for her travel papers.

Things are less certain for the nephews, who are in Israel. Earlier this month, the Israeli government passed legislation decreeing the 37,000 African migrants in the country would be deported in March to an unspecified African country, or jailed.

Durkee has been in contact with her church’s national office, which is keeping close tabs on the situation.

Gratitude from Eritrea

Tesfamichael and his family love Yellowknife and have no plans to leave.

He has returned to Eritrea since getting his Canadian citizenship in 2016 — he took a two-month trip last spring.

When he came back to Canada, he had a message for Durkee, from his mother in Eritrea.

She wanted Durkee to know how grateful she is that Tesfamichael has found such a great friend in Canada.