August 15, 2021

Eleanor Hegland crouches low to the ground, brushing moss aside and scooping cool water into her mouth.

It offers temporary relief from a relentless heat wave, as she makes her way through the Saskatchewan muskeg, gathering Labrador tea leaves.

"It's a medicine drink," said Hegland, a knowledge keeper in the Lac La Ronge Indian Band. Known locally as muskeg tea, it's brewed for an assortment of ailments: unhealthy guts, acne, colds.

But Hegland fears she soon won't be able to gather medicine from the land.

The muskeg is under threat.

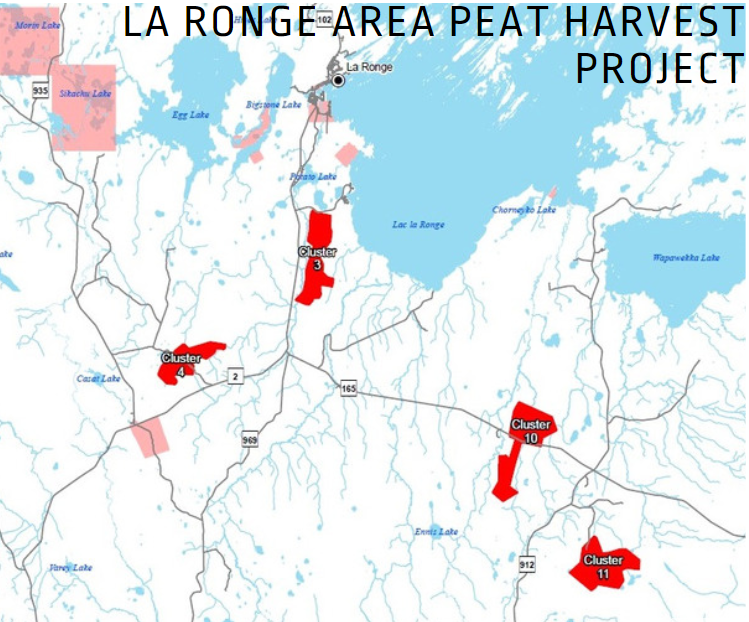

Quebec-based company Lambert Peat Moss has put forth a proposal to harvest 2,547 hectares of peat moss from four areas south of La Ronge, Sask., working in sections over the next 80 years. The company says 540 hectares would be harvested from Crown land at a time.

The land is host to the endangered woodland caribou and rare plants. Indigenous trappers and hunters rely on it for sustenance. Gatherers indulge in the abundance of plants, berries and mushrooms.

And so the proposal to clear the muskeg has drawn together a diverse community of opponents, including traditional land users, scientists and students.

The extent of the opposition to the project in Saskatchewan and beyond has grown alongside people's understanding of the muskeg's importance to the local way of life — and its delicate relationship to climate change.

Hegland grew up on the trapline that runs through the forest and muskeg, hunting, fishing and gathering along its route, until she was forced to attend residential school at age seven.

She never forgot the importance of nature.

"I'm getting old. I want to be able to leave a place for my kids and grandkids and future generations [where] it's safe, that it's OK to live on the land, it's OK to pick medicine."

Fired up

By July, the forests surrounding La Ronge are on fire again.

While plumes of smoke from nearby forests can't be seen in the heart of the muskeg, the smell has certainly reached it.

"Everyone who lives up here knows about the fires of 2015. Everyone got evacuated and lots of people lost their homes," said Kona Barreda, a local teacher at Senator Myles Venne School and member of the Lac La Ronge Indian Band.

Sitting in muskeg, she plunges her hand into the ground, causing water to rise up. Muskegs purify water, regulate its flow and act as natural firebreaks.

To harvest peat moss, though, companies drain the wetlands, let them dry out, then fluff the material before vacuuming it up.

The peat is sold to the horticulture industry, and is mixed into soil (or used to supplement soil) by major food producers and amateur gardeners alike.

Barreda created lesson plans explaining peat harvesting and muskegs for her science and English classes. As a result, her Grade 7 students became concerned about the proposed mining in the La Ronge area.

"We just wanted to do something to help," she said.

The COVID-19 pandemic dissuaded them from door-knocking and protesting publicly, so they created a petition, hoping for 1,000 signatures.

They got more than 20,000.

Barreda says she's encouraged by the support.

"I just don't want to see this getting destroyed, too," she said. "It's one of the last places we have left that's undisturbed and untouched."

WATCH | Take a drone tour of the muskeg near La Ronge:

'Scary' times for those living off land

To the north, Elder Miles Ratt hops down off a ladder. He’s building a land-camp for youth on the tip of Treaty 6 territory near Sucker River, Sask.

It will be a space for local Indigenous youth — many of whom have grown up in town — to learn traditional land-based skills and cultural practices.

He knows how healing the land can be.

But Ratt has also seen the area exploited before — and doesn't want to see it happen again.

"Trees are going down, mining companies are all over the place, and oh my goodness, it's now the muskeg," he said. "It's kind of scary for us that are out here, that live off the land."

Ratt says he's especially worried about the muskeg mining, given the ecological changes to the area he's seen during his lifetime. For example, he says, the millions of mayflies along his trapline seem to have all but vanished.

"We don't eat the flies, but the fish eat the flies and we eat the fish," he said. "Stuff like that. It's kind of slowly disappearing. Animals are moving in here that were never here. Their habitat is being destroyed."

Nature's carbon sink

Canada's peatlands cover about 12 per cent of the country's surface, and are mostly found in Ontario and Manitoba. But they're also in Quebec and Saskatchewan.

Often considered wastelands by outsiders, they're actually bursting with life.

Northern Saskatchewan's muskegs are dominated by non-vascular plants, like sphagnum mosses, a plant without roots. They're also typically peppered with stunted black spruce or tamarack trees, said Rob Wright, who worked for 25 years as a forest ecologist and science adviser for the Saskatchewan government. He has extensive experience in land management and forest ecology, including peatlands.

WATCH | A primer on peatlands and why they're critical to the climate change fight:

Peatlands have acted as a natural carbon capture system for centuries, but when they're disturbed, that sink is disrupted, leading to emissions.

And so, Wright says, the government needs to take climate change into account when assessing Lambert's proposal.

The land that makes up a muskeg is water-logged, acidic and nutrient-poor. It has low oxygen. The bogs are ombrotrophic: they collect moisture from rain and snow.

This means the material in bogs decomposes at a snail's pace, so they form layers of biomass over centuries. Peat moss develops below the surface as new life grows on top.

"You can get huge developments of peat that could be 10 metres thick," Wright said, noting that if these layers stay wet and undisturbed, they’ll potentially hang onto carbon for centuries.

But if you disturb the muskeg through mining and transfer the peat to gardens, it liberates that carbon.

"We better be damn sure we want to do that and that we can live with the consequences," said Wright.

While some might argue projects like the Lambert proposal are small fish in the big pond of global peat mining, Wright says it's a cumulative problem.

Peatlands around the world are increasingly seen as key climate change allies — especially as the bogs are at risk of global warming themselves.

As our climate warms, muskegs are drying out and catching fire, releasing carbon that has sometimes been sequestered for many years into the atmosphere.

- Canada's swamps are the secret weapon to fighting climate change, say experts

- Peat fires, like those raging in Siberia, will become more common in Canada

"We're getting into serious — pardon the pun — hot water here. We've got to take this seriously," said Wright.

Ratt said if the companies — and the government — ignore Indigenous people's opposition and proceed with projects like this, they need to compensate them.

But he’d rather the land be left alone entirely.

"It's so beautiful out here. We don't want to see it being destroyed by greed."

Band denounces project

Those fighting the Lambert proposal have been encouraged by local and provincial leadership.

The Official Opposition presented Barreda and her Grade 7 students' petition in Saskatchewan's Legislature in May.

The Lac La Ronge Indian Band — one of the largest First Nations in Canada — has also publicly opposed the plan.

"This isn't what we want," said Ty Roberts, who is the band's lands manager. "We have over 11,000 band members that use our lands for traditional purposes."

The land that will be affected by the proposal falls outside of the reserve, but Roberts said it's still on traditional First Nations land.

"When industry comes in like this, and the government wants to permit this type of activity, it does trigger a duty to consult and we have denounced it through that process," he said.

"We know that this land has been used by our people for generations, and we want to ensure that this land can be used in the future."

An attempt at reclamation

Lambert Peat Moss has told the community the project will rely on progressive reclamation, meaning once it harvests 540 hectares, no other areas will be harvested until others are "reclaimed." The company says it will replant vegetation that grew prior to the clearing and leave a buffer zone of peat.

The company estimates it takes five to 10 years for a sphagnum moss layer to be functional and about two decades for carbon sequestration and hydrological function to return.

Lambert's restoration goal is to return the area to peatland, but it anticipates it will take about 1,500 years to accumulate pre‐harvest thickness.

That promise of reclamation rings hollow for the muskeg's advocates.

"It's like restoring a deposit of coal after you've mined it and taken it away and burned it," Wright said. "If you are vigilant over the decades and centuries, that peat would build back up. But honestly, you'd have to be naive to believe that we're actually going to watch it for that long."

For peat's sake

In another corner of the bog, Miriam Körner howls with excitement. She's discovered a section of radial sundews, a carnivorous plant, on top of a mossy patch.

Originally from Germany, Körner fell in love with the area about two decades ago while travelling through the region. She never left and now lives in Potato Lake, Sask., which is just south of La Ronge and close to one of the areas Lambert is looking to mine.

"I always, always loved the muskeg, because it's one of the few old growth forests that are left in this area," Körner said.

Körner became alarmed after tuning in to one of Lambert's first public engagement sessions in late 2020. She always assumed this land would remain untouched.

"This area was safe, you know? It was safe for me, it was safe for the animals — and when I realized it wasn't, I knew I had to do something about that."

She started sharing information about the project with people in the area, and together they started "For Peat's Sake," a social media group centred around education and advocacy for northern Saskatchewan's peatlands. It now has hundreds of members. They’ve connected with traditional land users, biologists and even Manitobans who had similar concerns.

Körner is frustrated by the lack of urgency in protecting areas like the muskeg.

"We are in a climate crisis but people don’t treat it as a climate crisis."

According to Wright, there hasn't been an adequate survey and classification of the province's peatlands, so the Saskatchewan government can't know what's at stake when approving projects like this.

"The government should pause and work with the company to make their case that this thing is exploitable without the loss of a rare ecological feature in Saskatchewan," he said.

A spokesperson for the Saskatchewan Ministry of the Environment said the province has about 1.3 million hectares of land that are "peat-supporting wetland ecosites," with a large amount of sphagnum moss. However, "the ministry does not have specific data about what fraction of that area may support commercially viable peat mine operations."

Wright says politics often doesn't jive with smart land management.

"Good land management requires perspectives of decades or centuries — and politics often require perspectives of one or two years," he said.

The project doesn't have the greenlight yet. Lambert has to complete an environmental impact assessment. Saskatchewan's Ministry of Environment will review it, along with consultation efforts and public feedback on the project.

The minister of environment has the final say.

Wright says he doesn't hold much faith in impact assessments, which are produced by the companies, noting there's only been a handful of projects denied on the basis of an environmental assessment.

"It's a way of checking off some boxes," he said.

Hegland maintains the mining project will cut deeper than the layers of peat.

The muskeg helped her reconnect with the land and heal from the trauma of residential school, she said. Now she works with students who are facing their own intergenerational trauma and violence at home.

Hegland has them lay in the muskeg to release their pain; she said it will be impossible to teach youth how to learn the lessons and traditions of the land if it’s taken away.

"You're really destroying who we are. It's not just the muskeg. You're destroying a culture."